Sialkot

Sialkot

سیالکوٹ | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Calling code 052 | | |

| Old name | Sagala[7][8] or Sakala[9] | |

| Website | Municipal Corporation Sialkot | |

Sialkot (

Sialkot is believed to be the successor city of

The city has been noted for its entrepreneurial spirit and productive business climate which have made Sialkot an example of a small Pakistani city that has emerged as a "world-class manufacturing hub."[15] The relatively small city exported approximately $2.5 billion worth of goods in 2017, or about 10% of Pakistan's total exports.[15][16]

The city has been labeled as the Football manufacturing capital of the World,

History

Ancient

Founding

Sialkot is likely the capital of the

Greek

The

Indo-Greek

The ancient city was rebuilt, and made capital by the

Under Menander's rule, the city greatly prospered as a major trading centre renowned for its silk.[11][29] Menander embraced Buddhism in Sagala, after an extensive debating with the Buddhist monk Nagasena, as recorded in the Buddhist text Milinda Panha.[25][36] the text offers an early description of the city's cityscape and status as a prosperous trade centre with numerous green spaces.[37] Following his conversion, Sialkot developed as a major centre for Buddhist thought.[38]

Ancient Sialkot was recorded by Ptolemy in his 1st century CE work, Geography,[39][34] in which he refers to the city as Euthymedia (Εύθυμέδεια).[40]

Alchon Huns

Around 460 CE, the Alchon Huns invaded the region from Central Asia,[41] forcing the ruling family of nearby Taxila to seek refuge in Sialkot.[42] Sialkot itself was soon captured, and the city was made a significant centre of the Alchon Huns around 515,[43] during the reign of Toramana.[44] During the reign of his son, Mihirakula, the empire reached its zenith.[45] The Alchon Huns were defeated in 528 by a coalition of princes led by Prince Yashodharman[44]

Late antiquity

The city was visited by the Chinese traveller Xuanzang in 633,[46] who recorded the city's name the She-kie-lo.[47] Xuanzang reported that the city had been rebuilt approximately 15 li, or 2.5 miles, away from the city ruined by Alexander the Great.[48] During this time, Sialkot served as the political nucleus of the North Punjab region.[49] The city was then invaded in 643 by princes from Jammu, who held the city until the Muslim invasions during the medieval era.[50]

Medieval

Around the year 1000, Sialkot began to decline in importance as the nearby city of Lahore rose to prominence.

Sialkot became a part of the medieval

In the 1200s, Sialkot was the only area of western Punjab that was ruled by the

Sialkot became capital of Punjabi warlord and ruler

Sialkot was captured by armies of the Babur in 1520,

Pre-modern

Mughal

During the early Mughal era, Sialkot was made part of the subah, or "province", of Lahore.[50] According to Sikh tradition, Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, visited the city,[67] sometime in the early 16th century. He is said to have met Hamza Ghaus, a prominent Sufi mystic based in Sialkot, at a site now commemorated by the city's Gurdwara Beri Sahib.

During the

During the reign of Jahangir, the post was given to Safdar Khan, who rebuilt the city's fort, and oversaw a further increase in Sialkot's prosperity.[61] Numerous fine houses and gardens were built in the city during the Jehangir period.[72] During the Shah Jahan period, the city was placed under the rule of Ali Mardan Khan.[73]

The last Mughal emperor, Aurangzeb, appointed Ganga Dhar as faujdar of the city until 1654.[74] Rahmat Khan was then placed in charge of the city, and would build a mosque in the city.[75] Under Aurangzeb's reign, Sialkot became known as a great centre of Islamic thought and scholarship,[76][77] and attracted scholars because of the widespread availability of paper in the city.[78]

Post-Mughal

Following the decline of the Mughal empire after the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707, Sialkot and its outlying districts were left undefended and forced to defend itself. In 1739, the city was captured by

In the wake of the Persian invasion, Sialkot fell under the control of Pashtun powerful families from

Sikh

Sikh chieftains of the Bhangi Misl state encroached upon Sialkot, and had gained full control of the Sialkot region by 1786,[73][62] Sialkot was portioned into 4 quarters, under the control of Sardar Jiwan Singh, Natha Singh, Sahib Singh, and Mohar Singh, who invited the city's dispersed residents back to the city.[62]

The Bhangi rulers engaged in feuds with the neighbouring Sukerchakia Misl state by 1791,[73] and would eventually lose control of the city. The Sikh Empire of Ranjit Singh captured Sialkot from Sardar Jiwan Singh in 1808.[79] Sikh forces then occupied Sialkot until the arrival of the British in 1849.[81]

Modern

British

Sialkot, along with Punjab as a whole, was captured by the British following their victory over the Sikhs at the Battle of Gujrat in February 1849. During the British era, an official is known as The Resident who would, in theory, advise the Maharaja of Kashmir would reside in Sialkot during the wintertime.[82]

During the

Sialkot's modern prosperity began during the colonial era.

The British-Raj fought in The Second Boer War. A concentration camp in Sialkot held the detained Boer Prisoners-of-War.[88][89]

As a result of the city's prosperity, large numbers of migrants from

Partition

The first communal riots between Hindus/Sikhs and Muslims took place on 24 June 1946,[90] a day after the resolution calling for the establishment of Pakistan as a separate state. Sialkot remained peaceful for several months while communal riots had erupted in Lahore, Amritsar, Ludhiana, and Rawalpindi.[90] The predominantly Muslim population supported Muslim League and the Pakistan Movement.

While Muslim refugees had poured into the city escaping riots elsewhere, Sialkot's Hindu and Sikh communities began fleeing in the opposite direction towards India.[90] They initially congregated in fields outside the city, where some of Sialkot's Muslims would bid farewell to departing friends.[90] Hindu and Sikh refugees were unable to exit Pakistan towards Jammu on account of conflict in Kashmir, and were instead required to transit via Lahore.[90]

Post-independence

After independence in 1947 the

Following the demise of industry in the city, the government of West Pakistan prioritised the re-establishment of Punjab's decimated industrial base.[91] The province lead infrastructure projects in the area, and allotted abandoned properties to newly arrived refugees.[91] Local entrepreneurs also rose to fill the vacuum created by the departure of Hindu and Sikh businessmen.[91] By the 1960s, the provincial government laid extensive new roadways in the district, and connected it to trunk roads to link the region to the seaport in Karachi.[91]

During the

Geography

Climate

Sialkot features a humid subtropical climate (Cwa) under the Köppen climate classification, with four seasons. The post-monsoon season from mid-September to mid-November remains hot during the daytime, but nights are cooler with low humidity. In the winter from mid-November to March, days are mild to warm, with occasionally heavy rainfalls occurring. Temperatures in winter may drop to 0 °C or 32 °F, but maxima are very rarely less than 15 °C or 59 °F.

| Climate data for Sialkot (1991-2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 26.1 (79.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

42.2 (108.0) |

47.3 (117.1) |

48.9 (120.0) |

44.4 (111.9) |

41.1 (106.0) |

39.0 (102.2) |

37.2 (99.0) |

33.3 (91.9) |

27.2 (81.0) |

48.9 (120.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 17.4 (63.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

26.2 (79.2) |

32.9 (91.2) |

38.2 (100.8) |

38.8 (101.8) |

34.7 (94.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

31.1 (88.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

20.2 (68.4) |

29.4 (85.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.4 (52.5) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.4 (66.9) |

25.5 (77.9) |

30.5 (86.9) |

32.1 (89.8) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.4 (84.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

24.3 (75.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.2 (55.8) |

23.1 (73.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

23.6 (74.5) |

17.5 (63.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

16.8 (62.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −3 (27) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

13.3 (55.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.3 (1.63) |

50.4 (1.98) |

52.4 (2.06) |

36.9 (1.45) |

18.9 (0.74) |

67.8 (2.67) |

293.2 (11.54) |

299.5 (11.79) |

102.7 (4.04) |

22.4 (0.88) |

9.6 (0.38) |

13.6 (0.54) |

1,008.7 (39.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 3.6 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 6.5 | 13.3 | 12.4 | 6.4 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 64.7 |

| Source: | |||||||||||||

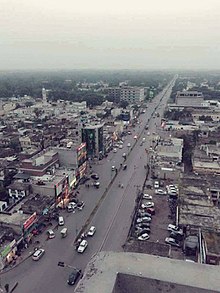

Cityscape

Sialkot's core is composed of the densely populated old city, while north of the city lies the vast colonial era Sialkot Cantonment – characterised by wide streets and large lawns. The city's industries have evolved in a "ribbon-like" pattern along the cities main arteries,[91] and are almost entirely dedicated to export.[91] The city's sporting good firms are not concentrated in any part of the city, but are instead spread throughout Sialkot.[91] Despite the city's overall prosperity, the local government has failed to meet Sialkot's basic infrastructure needs.[98]

Demographics

Religion

| Religious group |

1881[100][101][102] | 1891[103]: 68 | 1901[104]: 44 | 1911[105]: 20 | 1921[106]: 23 | 1931[107]: 26 | 1941[99]: 32 | 2017[108] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Islam |

28,865 | 63.08% | 31,920 | 57.94% | 39,350 | 67.9% | 40,613 | 62.61% | 44,846 | 63.5% | 69,700 | 69.03% | 90,706 | 65.39% | 653,346 | 95.96% |

| Hinduism |

12,751 | 27.86% | 17,978 | 32.64% | 13,433 | 23.18% | 15,417 | 23.77% | 15,808 | 22.38% | 18,670 | 18.49% | 29,661 | 21.38% | 1,102 | 0.16% |

| Sikhism |

1,942 | 4.24% | 1,797 | 3.26% | 2,236 | 3.86% | 4,290 | 6.61% | 3,433 | 4.86% | 4,931 | 4.88% | 8,431 | 6.08% | — | — |

| Jainism |

876 | 1.91% | 1,105 | 2.01% | 1,272 | 2.19% | 1,310 | 2.02% | 1,472 | 2.08% | 1,570 | 1.55% | 2,790 | 2.01% | — | — |

| Christianity |

— | — | 2,283 | 4.14% | 1,650 | 2.85% | 3,222 | 4.97% | 5,033 | 7.13% | 6,095 | 6.04% | 5,157 | 3.72% | 25,433 | 3.74% |

| Zoroastrianism |

— | — | 4 | 0.01% | 9 | 0.02% | 17 | 0.03% | 27 | 0.04% | 7 | 0.01% | — | — | — | — |

| Buddhism |

— | — | 0 | 0% | 6 | 0.01% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | — | — | — | — |

| Ahmadiyya |

— | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 958 | 0.14% |

| Others | 1,328 | 2.9% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1,963 | 1.42% | 25 | 0% |

| Total population | 45,762 | 100% | 55,087 | 100% | 57,956 | 100% | 64,869 | 100% | 70,619 | 100% | 100,973 | 100% | 138,708 | 100% | 680,864 | 100% |

Economy

Sialkot is a wealthy city relative to the rest of Pakistan, with a GDP (nominal) of $13 Billions and a per capita income in 2021 estimated at $18500.

Sialkot has been noted by Britain's The Economist magazine as a "world-class manufacturing hub" with strong export industries.[15] As of 2017, Sialkot exported US$2.5 billion worth of goods which is equal to 10% of Pakistan's total exports (US$25 billion).[109] 250,000 residents are employed in Sialkot's industries,[91] with most enterprises in the city being small and funded by family savings.[98] Sialkot's Chamber of Commerce had over 6,500 members in 2010, with most active in the leather, sporting goods, and surgical instruments industry.[98] The Sialkot Dry Port offers local producers quick access to Pakistani Customs, as well as to logistics and transportation.[15]

Despite being cut off from its historic economic heartland in Kashmir, Sialkot has managed to position itself into one of Pakistan's most prosperous cities, exporting up to 10% of all Pakistani exports.[15] Its sporting goods firms have been particularly successful, and have produced items for global brands such as Nike, Adidas, Reebok, and Puma.[91] Balls for the 2014 FIFA World Cup, 2018 FIFA World Cup and 2022 FIFA World Cup were made by Forward Sports, a Sialkot-based company.[110]

Sialkot's business community has joined with the local government to maintain the city's infrastructure, as the local government has limited capacity to fund such maintenance.[91] The business community was instrumental in the establishment of Sialkot's Dry Port in 1985,[98] and further helped re-pave the city's roads.[15] Sialkot's business community also largely funded the Sialkot International Airport—opened in 2011 as Pakistan's first privately owned public airport.[15]

Sialkot is also the only city in Pakistan to have its very own commercial airline, Airsial. This airline is managed by the business community of Sialkot based at the Sialkot Chamber of Commerce and Industries and offers direct flights from Sialkot to Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.[111]

Industry

Sialkot is the world's largest producer of hand-sewn footballs, with local factories manufacturing 40–60 million footballs a year, amounting to roughly 60% of world production.[112] Since the 2014 FIFA World Cup, footballs for the official matches are being made by Forward Sports, a company based in Sialkot.[110] Clustering of sports goods industrial units has allowed for firms in Sialkot to become highly specialised, and to benefit from joint action and external economies.[113] There is a well-applied child labour ban, the Atlanta Agreement, in the industry since a 1997 outcry,[114] and the local industry now funds the Independent Monitoring Association for Child Labour to regulate factories.[98]

Sialkot is also the world's largest centre of surgical instrument manufacturing.

The city's surgical instrument manufacturing industry benefits from a clustering effect, in which larger manufacturers remain in close contact with smaller and specialised industries that can efficiently perform contracted work.[116] The industry is made up of a few hundred small and medium size enterprises, supported by thousands of subcontractors, suppliers, and those providing other ancillary services. The bulk of exports are destined for the United States and European Union.[116]

Sialkot first became a centre for sporting goods manufacturing during the colonial era. Enterprises were initially inaugurated for the recreation of British troops stationed along the

Sialkot is also noted for its leather goods. Leather for footballs is sourced from nearby farms,[98] while Sialkot's leather workers craft some of Germany's most prized leather lederhosen trousers.[15]

Sialkot also has a large share in the agricultural sector. It predominantly produces

Public-Private Partnerships

Sialkot has a productive relationship between the civic administration and the city's entrepreneurs,[118] that dates to the colonial era. Sialkot's infrastructure was paid for by local taxes on industry,[91] and the city was one of the few in British Raj to have its own electric utility company.[91]

Modern Sialkot's business community has assumed responsibility for developing infrastructure when the civic administration is unable to deliver requested services.[15] The city's Chamber of Commerce established the Sialkot Dry Port, the country's first dry-port in 1985 to reduce transit times by offering faster customs services.[15] Members of the Chamber of Commerce allowed paid fees to help resurface the city's streets.[15] The Sialkot International Airport was established by the local businesses community, is the only private airport in Pakistan.[109]

Transportation

Highways

A dual-carriageway connects Sialkot to the nearby city of Wazirabad, with onward connections throughout Pakistan via the N-5 National Highway, while another dual carriageway connects Sialkot to Daska, and onwards to Gujranwala and Lahore. Sialkot and Lahore are also connected through the motorway M11.[citation needed]

Rail

The Sialkot Junction railway station is the city's main railway station and is serviced by the Wazirabad–Narowal Branch Line of the Pakistan Railways. The Allama Iqbal Express travels daily from Sialkot to Karachi via Lahore, and then back to Sialkot.[citation needed]

Air

The Sialkot International Airport is located about 20 km from the center of the city near Sambrial. It was established in 2007 by spending 4 billion rupees by Sialkot business community. It is Pakistan's only privately owned public airport,[15] and offers flights throughout Pakistan, with also direct flights to Bahrain, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, France, the UK and Spain.[citation needed]

Notable people

Awards

In 1966, the

Twin towns – sister cities

Sialkot is twinned with:

Bolingbrook, Illinois, United States[121]

Bolingbrook, Illinois, United States[121]

See also

- Sialkot Chamber of Commerce and Industry

- List of educational institutions in Sialkot

- List of cities in Punjab, Pakistan by area

- Sialkot Stallions

- Shivala Teja Singh temple

Notes

- ^ 1881-1941: Data for the entirety of the town of Sialkot, which included Sialkot Municipality and Sialkot Cantonment.[99]: 32

- ^ 1931-1941: Including Ad-Dharmis

References

- ^ "JI demands Sialkot-wide holiday on Allama Iqbal's birthday". The Nation (newspaper). 7 November 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Administrators' appointments planned as Punjab LG system dissolves today". The Nation (newspaper). 31 December 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Sialkot DC transferred". Dawn (newspaper). 31 December 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ "MC Sialkot: Administrative Setup". Local Government Punjab. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ a b "POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL: PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT)" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Pakistan: Provinces and Major Cities – Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de.

- ^ Abdul Majeed Abid (28 December 2015). "Pakistan's Greek connection". The Nation. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ISBN 9781108009416. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Mushtaq Soofi (18 January 2013). "Ravi and Chenab: demons and lovers". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Pakistan City & Town Population List". Tageo.com website. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ ISBN 9781581159332. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ a b Man & Development. Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development. 2007.

- ^ JSTOR 44145212.

- ISBN 978-90-04-32900-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Pakistan's business climate If you want it done right". The Economist. 27 October 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Naz, Neelum. "Historical Perspective of Urban Development of Gujranwala". Dept. of Architecture, UET, Lahore. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ "World's Football Manufacturing Capital in Pakistan Gets a Green Makeover". 25 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Asian Development Bank". Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ a b Mehmood, Mirza, Faisal; Ali, Jaffri, Atif; Saim, Hashmi, Muhammad (21 April 2014). An assessment of industrial employment skill gaps among university graduates: In the Gujrat-Sialkot-Gujranwala industrial cluster, Pakistan. Intl Food Policy Res Inst. p. 2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Azhar, Annus; Adil, Shahid. "Effect of Agglomeration on Socio-Economic Outcomes: A District Level Panel study of Punjab" (PDF). Pakistan Institute of Developmental Economics. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Sialkot vital economic, industrial hub of country". www.thenews.com.pk. 10 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Horace Hayman; Masson, Charles (1841). Ariana Antiqua: A Descriptive Account of the Antiquities and Coins of Afghanistan. East India Company. p. 197.

sangala rebuilt.

- ^ Kumar, Rakesh (2000). Ancient India and World. Classical Publishing Company. p. 68.

- ^ Rapson, Edward James (1960). Ancient India: From the Earliest Times to the First Century A. D. Susil Gupta. p. 88.

Sakala, the modern Sialkot in the Lahore Division of the Punjab, was the capital of the Madras who are known in the later Vedic period (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad).

- ^ ISBN 9781581159332. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ISBN 9780520953567.

- ISBN 9781107190412.

- ^ Congress, Indian History (2007). Proceedings, Indian History Congress.

- ^ ISBN 9789384544843. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Society, Panjab University Arabic and Persian (1964). Journal.

- ^ Wilson, Horace Hayman; Masson, Charles (1841). Ariana Antiqua: A Descriptive Account of the Antiquities and Coins of Afghanistan. East India Company. p. 196.

sangala rebuilt.

- ^ Arrian (1884). The Anabasis of Alexander, Or the History of the Wars and Conquests of Alexander the Great. Hodder and Stoughton.

- ^ ISBN 9780230106406.

- ^ ISBN 9781108009416.

- ^ Wilson, Horace Hayman; Masson, Charles (1841). Ariana Antiqua: A Descriptive Account of the Antiquities and Coins of Afghanistan. East India Company.

- ISBN 978-81-208-0893-5.

- ^ Davids, Thomas William Rhys (1894). The Questions of King Milinda. Clarendon Press.

- ISBN 9781581159332.

- ^ Journal of Indian History. 1960.

- ISBN 9780520953567.

- ISBN 9781108121316.

- ISBN 9788180696510.

- ISBN 9781317242123.

- ^ ISBN 9783805339575.

- ISBN 9788120815407.

- ISBN 9780786725441.

- ISBN 9789004277144.

- ^ Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65 by Alexander Cunningha M: 2. Government central Press. 1871.

- ^ ISBN 9780199088324.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-7019-117-9.

- ISBN 978-9047423836. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ ISBN 9004102361.

- ^ ISBN 9788120706170. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ ISBN 9788120819948.

- ^ ISBN 9780810855038.

- ^ ISBN 9788170945253.

- ISBN 9788122000429.

- ISBN 9789047423836.

- ^ Hasan, Masudul (1965). Hand Book of Important Places in West Pakistan. Pakistan Social Service Foundation.

- ^ Pakistan Pictorial. Pakistan Publications. 1986.

- ^ a b c Afsos, Sher ʻAlī Jaʻfarī (1882). The Arāīs̲h-i-maḥfil: Or, The Ornament of the Assembly. J. W. Thomas, Baptist Mission Press.

- ^ ISBN 9781317336945.

- ^ Medieval Kashmir. Atlantic Publishers & Distri.

- ISBN 9788131732021. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Gujjarsalways pour down in countless hordes from hill and plain for loot of bullocks and buffalo. These ill-omened peoples are senseless oppressors. Previously, their deeds did not concern us because the territory was an enemy's. But they did the same senseless deeds after we had captured it. When we reached Sialkot, they swooped on the poor and needy folk who were coming out of the town to our camp and stripped them bare. I had the witless brigands apprehended, and ordered a few of them to be cut to pieces.'Babur Nama page 250 published by Penguin

- ^ al-Harawī, Niʻmatallāh (1829). History of the Afghans. Oriental Translation-Fund.

- ^ Dhillon, Iqbal S. (1998). Folk Dances of Panjab. Delhi: National Book Shop.

- ISBN 9789694071305.

- ^ Khan, Refaqat Ali (1976). The Kachhwahas under Akbar and Jahangir. Kitab Pub. House.

- ^ Khan, Ahmad Nabi (1977). Iqbal Manzil, Sialkot: An Introduction. Department of Archaeology & Museums, Government of Pakistan.

- ISBN 9780195475753.

- ^ Khan, Ahmad Nabi (1977). Iqbal Manzil, Sialkot: An Introduction. Department of Archaeology & Museums, Government of Pakistan.

- ^ a b c d e f Cotton, James Sutherland; Burn, Sir Richard; Meyer, Sir William Stevenson (1908). Imperial Gazetteer of India ... Clarendon Press.

- ISBN 9780195627596.

- ^ Khan, Ahmad Nabi (1977). Iqbal Manzil, Sialkot: An Introduction. Department of Archaeology & Museums, Government of Pakistan.

- ISBN 9788174503039.

- ^ The Pakistan Review. Ferozsons Limited. 1968.

- ^ Sahay, Binode Kumar (1968). Education and learning under the great Mughals, 1526–1707 A.D. New Literature Pub. Co.

- ^ a b c bahādur.), Muḥammad Laṭīf (Saiyid, khān (1891). History of the Panjáb from the Remotest Antiquity to the Present Time. Calcutta Central Press Company, limited.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ISBN 978-0-916994-12-9.

- ISBN 978-0-19-521939-5

- ISBN 9781473815872. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-19-087023-2.

- ISBN 9781108023245. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ISBN 9781845110949.

- ^ "Punjab pays tartan homage to Caledonia | World news | The Observer". Guardian. 25 April 2004. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-137-44818-7.

- ^ "Nicolaas Marthinus Janse van Rensburg". geni_family_tree. 1833. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ "Cornelis Petrus van Zyl". geni_family_tree. 9 November 1870. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ ISBN 9780141007502.

- ^ ISBN 9781137448170. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ISBN 1-85532-209-9, page 9

- ^ "Commemorating Sept 1965: Nation celebrates Defence Day with fervour". The Express Tribune. 7 September 2013.

- ^ "Defence Day celebrated with renewed pledges". Dawn. 7 September 2002.

- ^ The India-Pakistan Air War of 1965, Synopsis. Retrieved 26 May 2008 at the Internet Archive

- ^ "Sialkot Climate Normals 1971–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ "Sialkot Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ ISBN 9780821399897.

- ^ a b "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1941 VOLUME VI PUNJAB". Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- JSTOR saoa.crl.25057656. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- JSTOR saoa.crl.25057657. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- JSTOR saoa.crl.25057658. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1891 GENERAL TABLES BRITISH PROVINCES AND FEUDATORY STATES VOL I". Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1901 VOLUME I-A INDIA PART II-TABLES". Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1911 VOLUME XIV PUNJAB PART II TABLES". Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1921 VOLUME XV PUNJAB AND DELHI PART II TABLES". Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1931 VOLUME XVII PUNJAB PART II TABLES". Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ "Final Results (Census-2017)". Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ a b "How a small Pakistani city became a world-class manufacturing hub". The Economist. 29 October 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ a b http://www.thenews.com.pk/article-150235-Brazilian-ambassador-unveils-Pak-made-FIFA-soccer-ball [bare URL]

- ^ Rizvi, Muzaffar (22 August 2022). "AirSial gets nod to start international flights". Khaleej Times. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ISBN 9781847886101. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ISBN 9781845425838. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ Hasnain Kazim (16 March 2010). "The Football Stitchers of Sialkot". Spiegel International. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ "BMA – Fair Medical Trade". www.fairmedtrade.org.uk. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ a b c "Surgical Goods". Emerging Pakistan, Government of Pakistan website. 19 December 2017. Archived from the original on 28 June 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ "Sialkot — a city with many feathers in its cap". Dawn. 24 May 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "If you want it done right". The Economist. 27 October 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Commemorating Sept 1965: Nation celebrates Defence Day with fervour". Express Tribune. 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Defence Day celebrated with renewed pledges". DAWN.COM. 7 September 2002.

- ^ "About". bolingbrook.com. Village of Bolingbrook. Retrieved 31 October 2022.