Siege of Corfu (1716)

| Siege of Corfu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Seventh Ottoman–Venetian War | |||||||

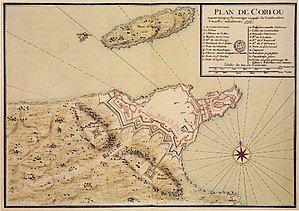

The city fortifications of Corfu in 1716 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 30,000 military and (mostly) civilian losses |

15,000 dead 56 cannons 8 siege mortars | ||||||

Location of Corfu city within Greece | |||||||

The siege of Corfu took place on 8 July – 21 August 1716, when the

Background

Following the

After the Great Turkish War concluded the Ottomans were from the outset determined to reverse these losses, beginning a reform of their

The opening move of the conflict was the invasion of the

The Ottomans immediately shifted their attention towards the western coasts of the Greek mainland, threatening the

Venetian preparations and initial Ottoman moves

The Venetians were well aware of Ottoman ambitions to capture the Ionian Islands, ambitions which dated to before the Great Turkish War. By 1716, it was clear that Corfu would be the next target.

The threat of an imminent Ottoman invasion led many of the inhabitants of the Ionian Islands to flee, some to Dalmatia, and others to Italy and Sicily.

In May, the Austrians warned Schulenburg that strong Ottoman forces under the

Passing by Zakynthos, the Ottoman admiral sent a letter demanding the island's submission, but did not otherwise divert his course. Likewise, only small detachments were landed at

The news spread panic on the island: the villagers fled into the fortifications of Corfu city, while others tried to flee, on whatever vessel they could find, to Otranto. Soon the panic spread to the suburbs of the city itself, with their inhabitants also abandoning their homes to find refuge inside the fortifications.[27] The situation became worse when Pisani, having to confront the far superior Ottoman fleet of 62 ships of the line with only his rowed vessels, decided not to risk a battle. After considering disembarking his crews to reinforce the garrison, he resolved to abandon his station in the Corfu Channel for the open sea, hoping to find Corner's squadron, which he had not heard from for 20 days.[25][26]

Rumours spread that the fleet had abandoned the island to its fate, leading to the outbreak of looting of the empty houses, as well as cases of arson, and even killings as the looters clashed.[27] Schulenburg, with the assistance of the Provveditore Generale da Mar, Antonio Loredan, tried to impose order while mustering his forces for the defence of the city: on 6 July, the Venetian commander disposed of about 1,000 German mercenaries, 400 Italian and Dalmatian soldiers, 500 Corfiots, and 300 Greeks from other regions.[28] The arrival of some 500 soldiers, under the Zakynthian captains Frangiskos Romas and the brothers Nikolaos and Frangiskos Kapsokefalos, represented a significant boost to Schulenburg's forces, but the situation remained problematic due to the low morale of the civilian population.[28]

Ottoman landings and siege of Corfu

The Ottoman siege of the city began on 8 July, with landings of some 4,000

On 10 July, the Ottoman ships recommenced landing troops, a process which continued without the Venetians making any attempt to interrupt it.[31] Clashes with the Canım Hoca Mehmed's men on the island continued over the next few days, as reinforcements started arriving for the defenders and the Ottomans alike: on 18 July Pisani returned to the island with a new, eighty-gun warship, two transports with 1,500 men, and a ship with food, while shortly after the troops of the serasker also began landing on the island.[32] The Ottoman forces were able to expand their occupation in the interior, pressing the inhabitants of the villages they captured into erecting field works. On 21 July, the Ottomans reached the suburbs of Mantouki and Gastrades.[28]

On the next day, the first ships of Venice's Christian allies appeared of

On 8 August, the situation began to change in favour of the defenders, as 1,500 troops with ample supplies and ammunition arrived to bolster the garrison, bringing with them news of the Austrian victory at the Battle of Petrovaradin on 5 August.[28] As a result, on the night of 18/19 August, the Venetians sortied against the Ottoman lines supported by fire from the galleys on both sides of the city. As the German contingent failed in its objectives, and the sortie was pushed back.[33] In turn, on the morning of 19 August, the Janissaries launched a mass assault on the fortifications, overrunning the bastion of St. Athanasios and part of the outer fortified belt and reaching the Scarpon Gate, where they hosted their banners. Schulenburg led a counterattack in person, and managed to push the Ottomans back.[28] On the next day, a storm broke out that wrought havoc with both fleets; some of the Christian ships unmoored by the winds and thrown towards the shore, while the Ottoman fleet suffered somewhat heavier losses.[28][33]

Undeterred, the Ottomans reorganized their forces on 20 August to resume their assault on the fortification, but on the next day, a Spanish squadron of six ships of the line appeared on the horizon.[28][33] During the night, the defenders could see much activity in the Ottoman lines, and fully expected to face another general assault on the next day; instead, come morning they found the Ottoman lines deserted. The Ottomans had abandoned the siege and began boarding their ships, in such haste that they left behind many supplies and much equipment, including some of the heaviest siege guns.[34] This presented an ideal opportunity for a Venetian attack, but Pisani refused to do so, contenting himself withdrawing his ships up in a line to block the southern exit of the Channel. When he did try to attack on 23 August, contrary wind prevented him from coming close to the Ottoman fleet, and on 24 August he returned to passively keeping watch over the southern exit of the Channel.[33] Pisani's reluctance to engage may be explained by past experience, which had shown that the management of the Venetians' Christian allies in battle was a difficult matter.[35][36] This allowed Canım Hoca Mehmed Pasha to move his fleet north to Butrint, and thence exit the Channel from the north and then sail south along the western coast of Greece and return to the safety of the Dardanelles. Pisani's fleet followed the Ottomans at a distance, while most of the other Christian ships, apart from the Knights of Malta, left in early September, once it became clear that the Ottomans were gone.[33]

The reason for the Ottoman withdrawal is still debated: some consider the arrival of the Spanish squadron, and news of the imminent arrival of a Portuguese squadron of nine ships, to have been decisive; other accounts tell of a mutiny in the besieging army; but the most likely reason is that, in the aftermath of the losses suffered at Petrovaradin, the serasker received urgent orders to wrap up operations so that his men could replenish the Ottoman forces in the northern Balkans.[34][37] The Ottomans lost some 15,000 dead in Corfu, along with 56 cannons and eight siege mortars, and large quantities of material, which they abandoned. The total losses, civilian and military, on the defenders' side, were 30,000.[38]

Aftermath

The Corfiots attributed the Ottoman withdrawal to the intervention of their patron saint, Saint Spyridon, and the miraculous storm,[28] while Venice celebrated the last major battlefield success in its history, heaping honours on Schulenburg similar to those enjoyed by Francesco Morosini after his conquest of the Morea a generation earlier.[39] He received a lifelong stipend of 5,000 ducats and a sword of honour, as well as a monument erected in his honour in front of the gateway to the Old Fortress in Corfu.[40] The defence of Corfu was also commemorated in Venice with the erection of a fourth stone lion at the entrance of the Venetian Arsenal, with the inscription "anno Corcyrae liberatae".[41]

As the Ottoman troops withdrew into the Balkan hinterland, Schulenburg and Loredan led 2,000 men to the mainland coast, and on 2 September recaptured the town of Butrint, one of the mainland exclaves of the Ionian Islands.[39] Two months later, the Venetian fleet recaptured Lefkada.[39][42] The arrival of naval reinforcements allowed the Venetian navy to engage the Ottoman fleet with more confidence. Christian victories in the Battle of Imbros (16 June 1717) and the Battle of Matapan (19 July 1717) removed the danger of a new Ottoman expedition in the Ionian Sea, and allowed the recovery of the two last mainland exclaves, Preveza and Vonitsa, on 19 October 1717 and 4 November 1717 respectively.[39][43]

Despite the successes, Venice was exhausted.[44] The Austrians, buoyed by their victories, were unwilling to discuss terms, until the Spanish launched an attack on the Habsburg possessions in Italy by sending the very fleet ostensibly being prepared to aid Venice to capture Sardinia in July 1717, and another to invade Sicily a year later. Faced with this stab in the back, the Austrians agreed to negotiations with the Ottomans, leading to the Treaty of Passarowitz (21 July 1718), in which Austria made considerable gains. Venice had to acknowledge the loss of the Morea, Tinos, and Aigina, but managed to retain the Ionian Islands and their mainland exclaves.[45]

The oratorio Juditha triumphans by Antonio Vivaldi is said to be an allegory of the victory of the Venetians over the Ottomans.

References

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 14–19.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 19–35.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 38, 41.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Setton 1991, pp. 421–426.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 39–43.

- ^ Setton 1991, pp. 428, 430–432.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Nani Mocenigo 1935, p. 319.

- ^ Setton 1991, pp. 427–428, 430.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, p. 43.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b c d e Chasiotis 1975, p. 44.

- ^ a b Anderson 1952, p. 246.

- ^ Nani Mocenigo 1935, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Nani Mocenigo 1935, p. 323.

- ^ Nani Mocenigo 1935, p. 324.

- ^ a b Setton 1991, p. 442.

- ^ a b c d Chasiotis 1975, p. 45.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 39, 45.

- ^ Setton 1991, pp. 434–435.

- ^ Prelli & Mugnai 2016, p. 45.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, p. 4.

- ^ Nani Mocenigo 1935, pp. 324–325.

- ^ a b Anderson 1952, p. 247.

- ^ a b Nani Mocenigo 1935, p. 325.

- ^ a b Chasiotis 1975, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Chasiotis 1975, p. 46.

- ^ Anderson 1952, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Nani Mocenigo 1935, pp. 325–326.

- ^ Anderson 1952, p. 248.

- ^ a b c d Anderson 1952, p. 249.

- ^ a b c d e Anderson 1952, p. 250.

- ^ a b Chasiotis 1975, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Setton 1991, pp. 443–444.

- ^ Nani Mocenigo 1935, p. 329.

- ^ Anderson 1952, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Nani Mocenigo 1935, p. 330.

- ^ a b c d Chasiotis 1975, p. 47.

- ^ Setton 1991, p. 444.

- ^ Prelli & Mugnai 2016, p. 23.

- ^ Anderson 1952, p. 251.

- ^ Anderson 1952, pp. 251–264.

- ^ Setton 1991, p. 446.

- ^ Setton 1991, pp. 446–450.

Sources

- OCLC 1015099422.

- Chasiotis, Ioannis (1975). "Η κάμψη της Οθωμανικής δυνάμεως" [The decline of Ottoman power]. In Christopoulos, Georgios A. & Bastias, Ioannis K. (eds.). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος ΙΑ΄: Ο Ελληνισμός υπό ξένη κυριαρχία (περίοδος 1669 - 1821), Τουρκοκρατία - Λατινοκρατία [History of the Greek Nation, Volume XI: Hellenism under Foreign Rule (Period 1669 - 1821), Turkocracy – Latinocracy] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 8–51. ISBN 978-960-213-100-8.

- Nani Mocenigo, Mario (1935). Storia della marina veneziana: da Lepanto alla caduta della Repubblica [History of the Venetian navy: from Lepanto to the fall of the Republic] (in Italian). Rome: Tipo lit. Ministero della Marina – Uff. Gabinetto.

- Prelli, Alberto; Mugnai, Bruno (2016). L'ultima vittoria della Serenissima: 1716 – L'assedio di Corfù (in Italian). Bassano del Grappa: itinera progetti. ISBN 978-88-88542-74-4.

- ISBN 0-87169-192-2.