List of sieges of Gibraltar

There have been fourteen recorded sieges of Gibraltar. Although the peninsula of Gibraltar is only 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) long and 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) wide, it occupies an extremely strategic location on the southern Iberian coast at the western entrance to the Mediterranean Sea. Its position just across the eponymous Strait from Morocco in North Africa, as well as its natural defensibility, have made it one of the most fought-over places in Europe.[1][2]

Only five of the sieges resulted in a change of rule. Seven were fought between Muslims and Catholics during Muslim rule, four between Spain and Britain from the Anglo-Dutch capture in 1704 to the end of the Great Siege in 1783, two between rival Catholic factions, and one between rival Muslim powers. Four of Gibraltar's changes in rule, including three sieges, took place over a matter of days or hours, whereas several other sieges had durations of months or years and claimed the lives of thousands without resulting in any change in rule.[3]

Background

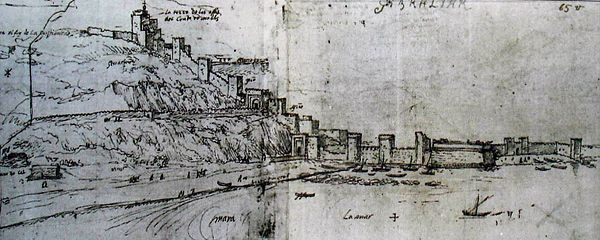

Gibraltar is a British territory and mountainous peninsula on the far southern coast of the Iberian peninsula, at one of the narrowest points in the Mediterranean, only 15 miles (24 km) from the coast of Morocco in North Africa. It is dominated by the steeply sloping Rock of Gibraltar, 426 metres (1,398 ft) high. A narrow, low-lying isthmus connects the peninsula to the Spanish mainland. High coastal cliffs and a rocky shoreline make it virtually impossible to attack from the east or south. The west side – occupied by the town of Gibraltar, which stands at the base of the Rock – and the northern approach across the isthmus have been densely fortified by its various occupants with numerous walls, towers and gun batteries. The geography of the peninsula provides considerable natural defensive advantages, which combined with its location have imbued Gibraltar with enormous military significance over the centuries.[4]

The first documented invasion of Gibraltar was by the

The Moorish presence in Gibraltar ended in 1462, when Enrique's son

Gibraltar lived in relative peace for over 200 years after the tenth siege, by which time the Reconquista was completed and Spain was unified under a single crown. The Rock's importance as a fortress diminished and its defences were neglected.

In the years following the thirteenth siege, tensions began to resurface between Britain and France,

Gibraltar played an important role in the Napoleonic Wars in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and in many later conflicts. Hitler drew up plans to besiege Gibraltar during the Second World War (Operation Felix), but the plans were never implemented and the Great Siege was the last military siege of Gibraltar.[21] Some historians discuss the closure of the Gibraltar–Spain border (part of an attempt by Spain to coerce the United Kingdom into ceding Gibraltar) from 1969 to 1985 as a "fifteenth siege";[22] as this differs from the other fourteen sieges in that it was not a conflict between opposing militaries, it is not included in this list.

List of sieges

| Name | Start date | End date | Description of dispute | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

First Siege of Gibraltar

|

August 1309 | 12 September 1309 | The first siege of Gibraltar lasted just over a month, ending on 12 September 1309. King a campaign on 27 July 1309 against Algeciras on the opposite side of the Bay of Gibraltar, but was frustrated by the Moors of Gibraltar, who smuggled supplies to Algeciras under the cover of darkness. Ferdinand ordered Alonso Pérez de Guzmán to attack Gibraltar. Guzmán attacked from the north and south simultaneously. When his men reached the top of the Rock, they set up catapults and began bombarding the town with rocks. The bombardment inflicted severe damage but failed to force the Moors out and a siege ensued, which was only broken when Ferdinand offered the Moors free passage back to Africa in exchange for their surrender of Gibraltar.[23][24]

|

Moors surrender Gibraltar to Castile[7] |

Second Siege of Gibraltar

|

1315 | 1315 | Exact dates unknown. A short-lived, unsuccessful attempt by the Moors to recapture Gibraltar six years after the first siege. The attempt was abandoned when Castilian naval and land forces approached Gibraltar to relieve it.[25][26] | Abandoned, Castile retains control[7] |

Third Siege of Gibraltar

|

February 1333 | 17 June 1333 | An attempt by | Castilians surrender to Moors[7] |

Fourth Siege of Gibraltar

|

26 June 1333 | August 1333 | In an attempt to make amends for his loss of Gibraltar earlier that month, Alfonso XI—feeling personal responsibility—attempted a counter-attack in late June 1333, before the Moors had chance to re-organise the city's defences. Alfonso attempted an amphibious assault, landing troops on the less fortified southern side of Gibraltar, but his commanders and troops were ill-disciplined. A large force rushed the Muhammed IV of Granada attempted to relieve Gibraltar, but Alfonso withdrew his forces behind a defensive ditch in the isthmus to the north of the Rock before Muhammed's army arrived. By August, Alfonso's army was itself effectively besieged and both sides were suffering, so the Moors offered a four-year truce, which Alfonso accepted.[29][30]

|

Moors retain control[7] |

Fifth Siege of Gibraltar

|

24 August 1349 | 27 March 1350 | After the end of the Iberian peninsula. A ten-year truce had been negotiated in return for the Moors' surrender of Algeciras, but the truce was broken after Abu Inan Faris overthrew his father in 1348. Alfonso XI, having failed to recapture the rock in his two prior sieges, marched on Gibraltar in August 1349, bringing with him six siege engines, and quickly settled down for a long siege. He built a large camp on the isthmus north of the town and brought his mistress and their illegitimate children to stay with him. The siege continued through the winter, and in February 1350, the Black Death broke out in Alfonso's camp. Alfonso's generals and the nobles and ladies with him in the camp begged him to lift the siege, but Alfonso vowed that he would not leave until Gibraltar was back in Christian hands. The king eventually caught the plague and he died on 27 March 1350 (Good Friday). The siege immediately ended with Alfonso's death. By that time, Yusuf I of Granada had almost reached Gibraltar with a relieving army, but he halted and allowed the Christian party to withdraw and return to Seville with the body of their king.[31][32]

|

Abandoned, Moors retain control[7] |

Sixth Siege of Gibraltar

|

1411 | 1411 | After the death of Alfonso XI at the fifth siege, Castilian ambitions of reconquering Gibraltar gave way to civil war, allowing tensions between Granada and Fez to surface. In 1374, the Moors of Fez ceded Gibraltar to the Granadan Moors, apparently in exchange for the latter's assistance with rebellions in Morocco. The garrison of Gibraltar revolted against Granada in 1410 and declared allegiance to Abu Said Uthman III of Fez, who also occupied much of the surrounding area. The following year, Granada launched a counter-offensive aimed at re-conquering the territory it had lost to Fez and succeeded in pushing the Moroccan Moors back as far as Gibraltar. There, they initiated a siege—the only one of Gibraltar's sieges to be contested between two Muslim powers. The Granadans repulsed several attempts to break out of the town before entering it and storming the Moorish Castle with clandestine help from inside. The garrison was forced to surrender and Gibraltar reverted to Granadan rule.[33][34] | Granada gains control from Fez[7] |

Seventh Siege of Gibraltar

|

August 1436 | 31 August 1436 | Throughout the Moorish rule of Gibraltar, the town was used as a base for bandit raids into Castilian territory. In 1436, Enrique Pérez de Guzmán, 2nd Count de Niebla (grandson of Alonso Pérez de Guzmán, who captured Gibraltar after the first siege) assembled a force of five thousand men with which he intended to storm Gibraltar and dismantle the raiders' base. He put his son, Juan Alonso de Guzmán, 1st Duke of Medina Sidonia in command of an army which marched from Tarifa to blockade the isthmus, while he led a fleet to land men on the beach. When Enrique arrived, he found the town's defences significantly stronger than he had anticipated – in particular, the sea wall had been extended since earlier sieges to prevent access to the Upper Rock from the beach. When his men landed, they found themselves caught between the tide and the sea wall, while the defending forces bombarded them with missiles. Enrique ordered his forces to withdraw, but was drowned when his boat capsized after several stranded men attempted to board it. Lacking the funds for an extended siege, Juan marched his army away, while the Moors recovered his father's body, decapitated it, and hung it in a basket above the town walls.[34][35]

|

Moors retain control[7] |

Eighth Siege of Gibraltar

|

August 1462 | 20 August 1462 | In August 1462, an inhabitant of then-Muslim Gibraltar defected to Tarifa, where he converted to Christianity. He informed the Governor of Tarifa, Alonso de Arcos that Gibraltar was largely undefended. A sceptical Alonso took a relatively small force to Gibraltar to attempt to verify the defector's claims. Upon arrival, Alonso's men took up concealed positions from which they could observe the town. They captured a Moorish patrol and tortured them for information, which confirmed the defector's claims. Lacking sufficient men to hold the town even if he managed to capture it, Alonso sent for reinforcements from nearby Christian towns and from Juan Alonso de Guzmán, 1st Duke of Medina Sidonia (who blockaded the isthmus in the seventh siege and whose father's body still hung above the town walls). After contingents arrived from local towns, Alonso launched an assault, which resulted in two days of heavy fighting, after which the Moors sent an emissary to offer terms for surrender. However, Alonso did not have the authority to accept the surrender, and had to await the arrival of a more senior noble. A contingent from Arcos stormed the town after the Jerez contingent attempted to accept the Moors' surrender, prompting the town's inhabitants to retreat inside the castle walls. With Gibraltar in Christian hands, a dispute broke out between the de Guzmáns and the Ponce de Leons over which family's standard would be raised above the castle. The Ponce de Leons' men withdrew when they believed the de Guzmáns had set a trap for them, leaving the Rock under the control of the de Guzmáns and the two families mortal enemies.[36][37] | De Guzmán family captures Gibraltar[7] |

Ninth Siege of Gibraltar

|

April 1466 | 26 July 1467 | At the end of the eighth siege, Juan Alonso de Guzmán took control of Gibraltar after a bitter dispute with Alonso Ponce de Leon, but shortly after, King Henry IV of Castile declared Gibraltar crown property, likely at the behest of the Ponce de Leons. When the Castilian nobles and clergy deposed Henry and declared his half brother Alfonso king, Juan quickly pledged his loyalty to Alfonso in return for a royal warrant granting Gibraltar to the house of de Guzmán, and Juan launched the ninth siege. The governor of Gibraltar almost immediately retreated into the Moorish Castle, which Juan blockaded in the expectation that the governor would shortly surrender. Ten months later, however, the governor was still barricaded inside the castle, so Juan brought in cannon to breach the walls and stormed the castle, forcing the defenders to retreat to the Tower of Homage (the innermost chamber of the castle). The defenders remained inside the tower hoping for rescue, but finally surrendered when none came after a further five months.[38][39] | De Guzmán family resumes control[7] |

Tenth Siege of Gibraltar

|

September 1506 | December 1506/January 1507 | In 1501, Queen Juan Alfonso Pérez de Guzmán, 3rd Duke of Medina Sidonia decided to exploit the instability and gathered an army to march on Gibraltar. He hoped that the city would simply open its gates to him, but it did not, and so began an unenthusiastic siege. After four months, the Archbishop of Seville persuaded the duke that it was dishonourable to continue the siege against the will of the inhabitants of Gibraltar, and the duke marched his army away, both sides having suffered minimal losses. Gibraltar was later awarded the title of "most loyal".[40][41]

|

Abandoned, Castilian crown retains control[7] |

| Eleventh Siege (the "Capture of Gibraltar") | 1 August 1704 | 3 August 1704 | Almost 200 years after the previous siege, and 240 years after the Spanish captured Gibraltar from the Moors, the eleventh siege arose from the Straits of Gibraltar. After unsuccessful attempts on several other ports, including Cadiz in 1702, the allied fleet commanded by Admiral George Rooke decided to take Gibraltar. The siege began on 1 August 1704 when the allies landed around 2,000 marines on the isthmus, cutting Gibraltar off from mainland Spain. The next day, Rooke ordered a squadron of vessels to form a line from Old Mole to New Mole along the west coast of the Rock. Early on 3 August, they began bombarding Gibraltar's fortifications. The bombardment lasted around six hours, after which a landing party attempted to storm the New Mole (which exploded as they did so, possibly because of English carelessness or a Spanish trap). The survivors eventually managed to proceed along the sea wall to Europa Point until a truce was agreed, allowing the governor until the next morning to agree with the city council to surrender, which they did at dawn on 4 August.[43][44]

|

Confederates capture Gibraltar[7] |

Twelfth Siege of Gibraltar

|

3 September 1704 | 31 March 1705 | After the capture of Gibraltar, the allies expected a counter-offensive, and in early September, it began. | Confederates retain control[7] |

Thirteenth Siege of Gibraltar

|

22 February 1727 | 23 June 1727 | In the words of the anonymous author of the Impartial Account of the Siege, the thirteenth siege "made rather more noise in the world in preparation than when undertaken". Act of Union in 1707). King Philip V of Spain felt that he had been forced by Louis XIV to sign the treaty, and the Spanish were determined to regain Gibraltar.[48] In January 1727, Philip claimed that Article X was null and void, citing several alleged violations of its terms by the British. The Marquis de las Torres began assembling an army, supported by contingents from across Catholic Europe, to attack Gibraltar; in response, the British began reinforcing the garrison. The thirteenth siege began on 22 February when the British fired on a party of Spanish workers in the neutral territory north of the Rock; from then on, the Spanish attempted to build batteries on the isthmus with which to bombard British batteries and the city walls, while the British attempted to halt Spanish progress. By 24 March, the Spanish had established batteries within range of the British defences and began a ten-day bombardment, inflicting considerable damage which the British struggled to repair. The Spanish pace was reduced by bad weather, which began in early April; it was not until 7 May that the bombardment began again in earnest. By 20 May, the Spanish supply chain could not keep up with the demands of the bombardment while the British were almost constantly able to resupply by sea. The Spanish offered a truce on 23 June, which was signed the next day.[49][50]

|

Britain retains control[51] |

| Fourteenth Siege (the "Great Siege of Gibraltar") | 24 June 1779 | 7 February 1783 | The fourteenth and final siege (the "Great Siege of Gibraltar") was the longest and most famous of Gibraltar's sieges. The allied with France and declared war on Britain, the primary ambition of which being to recover Gibraltar.[52] Bearing in mind the futility of previous sieges in which Gibraltar had been blockaded only by land, the Spanish launched a combined land and sea blockade in an attempt to starve the garrison into surrender. They bribed the sultan of Morocco into severing trade with Gibraltar and built booms to prevent ships landing supplies, while simultaneously blockading the isthmus with over 13,000 men, where work began on rebuilding the batteries from the previous siege 50 years earlier.[53] From the summer of 1780, Spanish forces attempted to bombard Gibraltar with fire ships and gunboats, while the British attempted to devise ways of frustrating these attacks as well as bombarding the Spanish camp with the few cannon that could reach.[54] The Spanish bombardment continued throughout the siege, though slackening at times, but the naval blockade was intermittent, meaning that merchants were able to land and sell supplies to the garrison, preventing it from being starved into submission. The merchants also conveyed those civilians who could afford it away from the Rock, and so the civilian population gradually declined.[55] The siege concluded after Britain ceded East and West Florida and Menorca to Spain in exchange for Gibraltar in lengthy negotiations facilitated by France.[19]

|

Britain retains control[51] |

See also

References

- General

- Dennis, Philip (1977). Gibraltar. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles Ltd. ISBN 0-7153-7358-7.

- Fa, Darren; ISBN 978-1-84603-016-1.

- ISBN 0-7091-4352-4.

- ISBN 0-8386-3237-8.

- Rose, Edward P.F. (2001). "Military Engineering on the Rock of Gibraltar and its Geoenvironmental Legacy". In Ehlen, Judy; Harmon, Russell S. (eds.). The Environmental Legacy of Military Operations. ISBN 0-8137-4114-9.

- Specific

- ^ Fa & Finlayson, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Rose, p. 95.

- ^ Hills, p. 95.

- ^ Dennis, pp. 7–8

- ^ Fa & Finlayson, p. 5.

- ^ Jackson, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Fa & Finlayson, p. 9.

- ^ Hills, p. 96.

- ^ Fa & Finlayson, pp. 9, 20–22.

- ^ Jackson, p. 93.

- ^ Jackson, p. 111.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 115–120.

- ^ Jackson, p. 124.

- ^ Jackson, p. 132.

- ^ Jackson, p. 141.

- ^ Jackson, p. 14.

- ^ Jackson, p. 149–150.

- ^ Jackson, p. 152–153.

- ^ a b Jackson, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Finlayson, p. 10.

- ^ Jackson, p. 181.

- ^ Jackson p. 317.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Hills, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Jackson, p. 42.

- ^ Hills, p. 54.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Hills, pp. 56–59.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Hills, p. 60–62.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Hills, p. 62–66.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 54–56.

- ^ a b Hills, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Jackson, p. 56.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 57–60.

- ^ Hills, pp. 91–95.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Hills, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Hills, pp. 102–105.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 94–99.

- ^ Hills, pp. 168–175.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 103–111.

- ^ Hills, pp. 184–200.

- ^ Hills, p. 276.

- ^ Jackson, p. 113.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 123–132.

- ^ Hills, pp. 262–276.

- ^ a b Fa & Finlayson, p. 10.

- ^ Jackson, p. 150.

- ^ Jackson, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Jackson, p. 159.

- ^ Jackson, p. 164.