Silicon dioxide

A sample of silicon dioxide

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Silicon dioxide

| |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.028.678 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E551 (acidity regulators, ...) |

| 200274 | |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Silicon+dioxide |

PubChem CID

|

|

RTECS number

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

| SiO2 | |

| Molar mass | 60.08 g/mol |

| Appearance | Transparent or white |

| Density | 2.648 (α-quartz), 2.196 (amorphous) g·cm−3[1] |

| Melting point | 1,713 °C (3,115 °F; 1,986 K) (amorphous)[1]: 4.88 to |

| Boiling point | 2,950 °C (5,340 °F; 3,220 K)[1] |

| −29.6·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Thermal conductivity

|

12 (|| c-axis), 6.8 (⊥ c-axis), 1.4 (am.) W/(m⋅K)[1]: 12.213 |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.544 (o), 1.553 (e)[1]: 4.143 |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 20 mppcf (80 mg/m3/%SiO2) (amorphous)[2] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 6 mg/m3 (amorphous)[2] Ca TWA 0.05 mg/m3[3] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

3000 mg/m3 (amorphous)[2] Ca [25 mg/m3 (cristobalite, tridymite); 50 mg/m3 (quartz)][3] |

| Related compounds | |

Related diones

|

Carbon dioxide Tin dioxide Lead dioxide |

Related compounds

|

Silicon monoxide Silicon sulfide

|

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

42 J·mol−1·K−1[4] |

Std enthalpy of (ΔfH⦵298)formation |

−911 kJ·mol−1[4] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula SiO2, commonly found in nature as quartz.[5][6] In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is abundant as it comprises several minerals and synthetic products. All forms are white or colorless, although impure samples can be colored.

Silicon dioxide is a common fundamental constituent of glass.

Structure

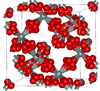

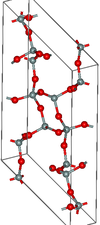

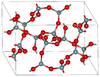

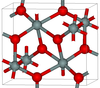

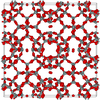

In the majority of silicon dioxides, the silicon atom shows tetrahedral coordination, with four oxygen atoms surrounding a central Si atom (see 3-D Unit Cell). Thus, SiO2 forms 3-dimensional network solids in which each silicon atom is covalently bonded in a tetrahedral manner to 4 oxygen atoms. [8][9] In contrast, CO2 is a linear molecule. The starkly different structures of the dioxides of carbon and silicon are a manifestation of the double bond rule.[10]

Based on the crystal structural differences, silicon dioxide can be divided into two categories: crystalline and non-crystalline (amorphous). In crystalline form, this substance can be found naturally occurring as quartz, tridymite (high-temperature form), cristobalite (high-temperature form), stishovite (high-pressure form), and coesite (high-pressure form). On the other hand, amorphous silica can be found in nature as opal and diatomaceous earth. Quartz glass is the form of intermediate state between this structure.[11]

All of this

Polymorphism

Faujasite silica, another polymorph, is obtained by the dealumination of a low-sodium, ultra-stable Y zeolite with combined acid and thermal treatment. The resulting product contains over 99% silica, and has high crystallinity and specific surface area (over 800 m2/g). Faujasite-silica has very high thermal and acid stability. For example, it maintains a high degree of long-range molecular order or crystallinity even after boiling in concentrated hydrochloric acid.[18]

Molten SiO2

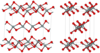

Molecular SiO2

The molecular SiO2 has a linear structure like CO2. It has been produced by combining silicon monoxide (SiO) with oxygen in an argon matrix. The dimeric silicon dioxide, (SiO2)2 has been obtained by reacting O2 with matrix isolated dimeric silicon monoxide, (Si2O2). In dimeric silicon dioxide there are two oxygen atoms bridging between the silicon atoms with an Si–O–Si angle of 94° and bond length of 164.6 pm and the terminal Si–O bond length is 150.2 pm. The Si–O bond length is 148.3 pm, which compares with the length of 161 pm in α-quartz. The bond energy is estimated at 621.7 kJ/mol.[21]

Natural occurrence

Geology

SiO2 is most commonly encountered in nature as quartz, which comprises more than 10% by mass of the Earth's crust.[22] Quartz is the only polymorph of silica stable at the Earth's surface. Metastable occurrences of the high-pressure forms coesite and stishovite have been found around impact structures and associated with eclogites formed during ultra-high-pressure metamorphism. The high-temperature forms of tridymite and cristobalite are known from silica-rich volcanic rocks. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand.[23]

Biology

Even though it is poorly soluble, silica occurs in many plants such as rice. Plant materials with high silica phytolith content appear to be of importance to grazing animals, from chewing insects to ungulates. Silica accelerates tooth wear, and high levels of silica in plants frequently eaten by herbivores may have developed as a defense mechanism against predation.[24][25]

Silica is also the primary component of

Silicification in and by cells has been common in the biological world and it occurs in bacteria, protists, plants, and animals (invertebrates and vertebrates).[27]

Prominent examples include:

- Tests or frustules (i.e. shells) of diatoms, Radiolaria, and testate amoebae.[6]

- Silica phytoliths in the cells of many plants, including Equisetaceae, many grasses, and a wide range of dicotyledons.

- The spicules forming the skeleton of many sponges.

Crystalline minerals formed in the physiological environment often show exceptional physical properties (e.g., strength, hardness, fracture toughness) and tend to form hierarchical structures that exhibit microstructural order over a range of scales. The minerals are crystallized from an environment that is undersaturated concerning silicon, and under conditions of neutral pH and low temperature (0–40 °C).

Uses

Structural use

About 95% of the commercial use of silicon dioxide (sand) occurs in the construction industry, e.g. for the production of concrete (

Certain deposits of silica sand, with desirable particle size and shape and desirable clay and other mineral content, were important for sand casting of metallic products.[28] The high melting point of silica enables it to be used in such applications such as iron casting; modern sand casting sometimes uses other minerals for other reasons.

Crystalline silica is used in

Precursor to glass and silicon

Silica is the primary ingredient in the production of most

The structural geometry of silicon and oxygen in glass is similar to that in quartz and most other crystalline forms of silicon and oxygen with silicon surrounded by regular tetrahedra of oxygen centres. The difference between the glass and crystalline forms arises from the connectivity of the tetrahedral units: Although there is no long-range periodicity in the glassy network ordering remains at length scales well beyond the SiO bond length. One example of this ordering is the preference to form rings of 6-tetrahedra.[31]

The majority of

Silicon dioxide is used to produce elemental

Fumed silica

Fumed silica, also known as pyrogenic silica, is prepared by burning SiCl4 in an oxygen-rich hydrogen flame to produce a "smoke" of SiO2.[15]

It can also be produced by vaporizing quartz sand in a 3000 °C electric arc. Both processes result in microscopic droplets of amorphous silica fused into branched, chainlike, three-dimensional secondary particles which then agglomerate into tertiary particles, a white powder with extremely low bulk density (0.03-0.15 g/cm3) and thus high surface area.[33] The particles act as a thixotropic thickening agent, or as an anti-caking agent, and can be treated to make them hydrophilic or hydrophobic for either water or organic liquid applications

Food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical applications

Silica, either colloidal, precipitated, or pyrogenic fumed, is a common additive in food production. It is used primarily as a flow or anti-

In cosmetics, silica is useful for its light-diffusing properties[35] and natural absorbency.[36]

Semiconductors

Silicon dioxide is widely used in the semiconductor technology

- for the primary passivation (directly on the semiconductor surface),

- as an original hafnium oxideor similar with higher dielectric constant compared to silicon dioxide,

- as a dielectric layer between metal (wiring) layers (sometimes up to 8–10) connecting elements and

- as a second passivation layer (for protecting semiconductor elements and the metallization layers) typically today layered with some other dielectrics like silicon nitride.

Because silicon dioxide is a native oxide of silicon it is more widely used compared to other semiconductors like gallium arsenide or indium phosphide.

Silicon dioxide could be grown on a silicon

The process of silicon surface passivation by

Other

In its capacity as a

Silica is used in the extraction of DNA and RNA due to its ability to bind to the nucleic acids under the presence of chaotropes.[43]

Pure silica (silicon dioxide), when cooled as fused quartz into a glass with no true melting point, can be used as a glass fibre for fibreglass.

Insecticide

Silicon dioxide has been researched for agricultural applications as a potential insecticide.[45][46]

Production

Silicon dioxide is mostly obtained by mining, including sand mining and purification of quartz. Quartz is suitable for many purposes, while chemical processing is required to make a purer or otherwise more suitable (e.g. more reactive or fine-grained) product.[citation needed]

Precipitated silica

Precipitated silica or amorphous silica is produced by the acidification of solutions of sodium silicate. The gelatinous precipitate or silica gel, is first washed and then dehydrated to produce colorless microporous silica.[15] The idealized equation involving a trisilicate and sulfuric acid is:

Approximately one billion kilograms/year (1999) of silica were produced in this manner, mainly for use for polymer composites – tires and shoe soles.[22]

On microchips

Thin films of silica grow spontaneously on

or wet oxidation with H2O.[48][49]

The native oxide layer is beneficial in

Laboratory or special methods

From organosilicon compounds

Many routes to silicon dioxide start with an organosilicon compound, e.g., HMDSO,[51] TEOS. Synthesis of silica is illustrated below using tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS).[52] Simply heating TEOS at 680–730 °C results in the oxide:

Similarly TEOS combusts around 400 °C:

TEOS undergoes

Other methods

Being highly stable, silicon dioxide arises from many methods. Conceptually simple, but of little practical value, combustion of silane gives silicon dioxide. This reaction is analogous to the combustion of methane:

However the chemical vapor deposition of silicon dioxide onto crystal surface from silane had been used using nitrogen as a carrier gas at 200–500 °C.[54]

Chemical reactions

Silicon dioxide is a relatively inert material (hence its widespread occurrence as a mineral). Silica is often used as inert containers for chemical reactions. At high temperatures, it is converted to silicon by reduction with carbon.

Fluorine reacts with silicon dioxide to form SiF4 and O2 whereas the other halogen gases (Cl2, Br2, I2) are unreactive.[15]

Most forms of silicon dioxide are attacked ("etched") by hydrofluoric acid (HF) to produce hexafluorosilicic acid:[12]

- SiO2 + 6 HF → H2SiF6 + 2 H2O

Stishovite does not react to HF to any significant degree.[55] HF is used to remove or pattern silicon dioxide in the semiconductor industry.

Silicon dioxide acts as a Lux–Flood acid, being able to react with bases under certain conditions. As it does not contain any hydrogen, non-hydrated silica cannot directly act as a Brønsted–Lowry acid. While silicon dioxide is only poorly soluble in water at low or neutral pH (typically, 2 × 10−4 M for quartz up to 10−3 M for cryptocrystalline chalcedony), strong bases react with glass and easily dissolve it. Therefore, strong bases have to be stored in plastic bottles to avoid jamming the bottle cap, to preserve the integrity of the recipient, and to avoid undesirable contamination by silicate anions.[56]

Silicon dioxide dissolves in hot concentrated alkali or fused hydroxide, as described in this idealized equation:[15]

Silicon dioxide will neutralise basic metal oxides (e.g. sodium oxide, potassium oxide, lead(II) oxide, zinc oxide, or mixtures of oxides, forming silicates and glasses as the Si-O-Si bonds in silica are broken successively).[12] As an example the reaction of sodium oxide and SiO2 can produce sodium orthosilicate, sodium silicate, and glasses, dependent on the proportions of reactants:[15]

- .

Examples of such glasses have commercial significance, e.g. soda–lime glass, borosilicate glass, lead glass. In these glasses, silica is termed the network former or lattice former.[12] The reaction is also used in blast furnaces to remove sand impurities in the ore by neutralisation with calcium oxide, forming calcium silicate slag.

Silicon dioxide reacts in heated

Silicon dioxide reacts with elemental silicon at high temperatures to produce SiO:[12]

Water solubility

The solubility of silicon dioxide in water strongly depends on its crystalline form and is three to four times higher for silica[clarification needed] than quartz; as a function of temperature, it peaks around 340 °C (644 °F).[58] This property is used to grow single crystals of quartz in a hydrothermal process where natural quartz is dissolved in superheated water in a pressure vessel that is cooler at the top. Crystals of 0.5–1 kg can be grown for 1–2 months.[12] These crystals are a source of very pure quartz for use in electronic applications.[15] Above the critical temperature of water 647.096 K (373.946 °C; 705.103 °F) and a pressure of 22.064 megapascals (3,200.1 psi) or higher, water is a supercritical fluid and solubility is once again higher than at lower temperatures.[59]

Health effects

Silica ingested orally is essentially nontoxic, with an LD50 of 5000 mg/kg (5 g/kg).[22] A 2008 study following subjects for 15 years found that higher levels of silica in water appeared to decrease the risk of dementia. An increase of 10 mg/day of silica in drinking water was associated with a decreased risk of dementia of 11%.[60]

Inhaling finely divided crystalline silica dust can lead to

Occupational hazard

Silica is an occupational hazard for people who do

Crystalline silica is an

Pathophysiology

In the body, crystalline silica particles do not dissolve over clinically relevant periods. Silica crystals inside the lungs can activate the NLRP3

Regulation

Regulations restricting silica exposure 'with respect to the silicosis hazard' specify that they are concerned only with silica, which is both crystalline and dust-forming.[68][69][70][71][72][73]

In 2013, the U.S.

Crystalline forms

SiO2, more so than almost any material, exists in many crystalline forms. These forms are called

| Form | Crystal symmetry Pearson symbol, group no. |

ρ (g/cm3) |

Notes | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-quartz | rhombohedral (trigonal)

hP9, P3121 No.152[74] |

2.648 | Helical chains making individual single crystals optically active; α-quartz converts to β-quartz at 846 K |

|

| β-quartz | hexagonal

hP18, P6222, No. 180[75] |

2.533 | Closely related to α-quartz (with an Si-O-Si angle of 155°) and optically active; β-quartz converts to β-tridymite at 1140 K |

|

| α-tridymite | orthorhombic

oS24, C2221, No.20[76] |

2.265 | Metastable form under normal pressure |

|

| β-tridymite | hexagonal hP12, P63/mmc, No. 194[76] |

Closely related to α-tridymite; β-tridymite converts to β-cristobalite at 2010 K |

| |

| α-cristobalite | tetragonal

tP12, P41212, No. 92[77] |

2.334 | Metastable form under normal pressure |

|

| β-cristobalite | cubic cF104, Fd3m, No.227[78] |

Closely related to α-cristobalite; melts at 1978 K |

| |

| keatite | tetragonal tP36, P41212, No. 92[79] |

3.011 | Si5O10, Si4O8, Si8O16 rings; synthesised from glassy silica and alkali at 600–900 K and 40–400 MPa |

|

| moganite | monoclinic

mS46, C2/c, No.15[80] |

Si4O8 and Si6O12 rings |

| |

| coesite | monoclinic mS48, C2/c, No.15[81] |

2.911 | Si4O8 and Si8O16 rings; 900 K and 3–3.5 GPa |

|

| stishovite | tetragonal tP6, P42/mnm, No.136[82] |

4.287 | One of the densest (together with seifertite) polymorphs of silica; rutile-like with 6-fold coordinated Si; 7.5–8.5 GPa |

|

| seifertite | orthorhombic oP, Pbcn[83] |

4.294 | One of the densest (together with stishovite) polymorphs of silica; is produced at pressures above 40 GPa.[84] |

|

| melanophlogite | cubic (cP*, P4232, No.208)[7] or tetragonal (P42/nbc)[85] | 2.04 | Si5O10, Si6O12 rings; mineral always found with hydrocarbons in interstitial spaces - a clathrasil (silica clathrate)[86] |

|

| fibrous W-silica[15] |

orthorhombic oI12, Ibam, No.72[87] |

1.97 | Like SiS2 consisting of edge sharing chains, melts at ~1700 K

|

|

| 2D silica[88] | hexagonal | Sheet-like bilayer structure |

|

Safety

Inhaling finely divided crystalline silica can lead to severe inflammation of the

Other names

This extended list enumerates synonyms for silicon dioxide; all of these values are from a single source; values in the source were presented capitalized.[90]

- CAS 112945-52-5

- Acitcel

- Aerosil

- Amorphous silica dust

- Aquafil

- CAB-O-GRIP II

- CAB-O-SIL

- CAB-O-SPERSE

- Catalogue

- Colloidal silica[citation needed]

- Colloidal silicon dioxide

- Dicalite

- DRI-DIE Insecticide 67

- FLO-GARD

- Fossil flour

- Fumed silica

- Fumed silicon dioxide

- HI-SEL

- LO-VEL

- Ludox

- Nalcoag

- Nyacol

- Santocel

- Silica

- Silica aerogel

- Silica, amorphous

- Silicic anhydride

- Silikill

- Synthetic amorphous silica

- Vulkasil

See also

References

- ^ ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0552". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0682". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ISBN 9780471024040.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- ^ a b Skinner BJ, Appleman DE (1963). "Melanophlogite, a cubic polymorph of silica" (PDF). Am. Mineral. 48: 854–867. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- ISBN 978-0-387-36687-6, retrieved 2023-10-08

- S2CID 255234311.

- ISBN 978-0-19-855961-0.

- ISBN 978-0-444-41683-4, retrieved 2023-09-12

- ^ ISBN 0-12-352651-5

- ISBN 9780812213775.

- ISBN 9783319540542.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-08-022057-4.

- ISBN 9780198553700.

- PMID 11679696.

- .

- S2CID 6109212. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2016-06-04. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- ISBN 9783527306473.

- ^ ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ISBN 9781405160544.

- PMID 16638012.

- PMID 18341561.

- ISSN 0950-0618.

- doi:10.2113/0540291.

- ^ Nevin CM (1925). Albany moulding sands of the Hudson Valley. University of the State of New York at Albany.

- ^ a b c d Greenhouse S (23 Aug 2013). "New Rules Would Cut Silica Dust Exposure". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 Aug 2013.

- S2CID 124299526.

- S2CID 4344891.

- OCLC 430678988.

- ^ a b "Cab-O-Sil Fumed Metal Oxides".

- PMID 34075083.

- ISBN 9781842145654.

These soft-focus pigments, mainly composed of polymers, micas and talcs covered with rough or spherical particles of small diameters, such as silica or titanium dioxide, are used to optically reduce the appearance of wrinkles. These effects are obtained by optimizing outlines of wrinkles and reducing the difference of brightness due to diffuse reflection.

- ISBN 9781842145654.

The silica is a multiporous ingredient, which absorbs the oil and sebum.

- ISBN 9780801886393.

- ^ ISBN 9780262294324.

- ^ ISBN 9789812814456.

- ^ a b c "Martin Atalla in Inventors Hall of Fame, 2009". Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ ISBN 9783319325217.

- ^ a b "Dawon Kahng". National Inventors Hall of Fame. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ISBN 9780470010259.

- ^ Calderone J (20 Aug 2015). "This cloud-like, futuristic material has been sneaking its way into your life since 1931". Business Insider. Retrieved 11 Feb 2019.

- PMID 34262071.

- ^ PMID 28718769.

- ISBN 9781574446753.

- ISBN 9780824755638.

- ISBN 9780471924784.

- ^ Riordan M (2007). "The Silicon Dioxide Solution: How physicist Jean Hoerni built the bridge from the transistor to the integrated circuit". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 11 Feb 2019.

- S2CID 127735545.

- S2CID 236182027.

- .

- ISBN 9780471924784.

- ^ Fleischer M (1962). "New mineral names" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 47 (2). Mineralogical Society of America: 172–174. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-22.

- ISBN 9781133172482.

- (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-19.

- ^ Fournier RO, Rowe JJ (1977). "The solubility of amorphous silica in water at high temperatures and high pressures" (PDF). Am. Mineral. 62: 1052–1056. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- Bibcode:2019EGUGA..21.4614O.

- PMID 19064650.

- ^ "Work Safely with Silica". CPWR - The Center for Construction Research and Training. Retrieved 11 Feb 2019.

- ^ "Action Plan for Lupus Research". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. National Institutes of Health. 2017. Retrieved 11 Feb 2019.

- PMID 1648030.

- ^ "Worker Exposure to Silica during Countertop Manufacturing, Finishing and Installation" (PDF). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved 26 Feb 2015.

- PMID 18604214.

- . DHHS (NIOSH) Publication Number 86-102.

- ^ NIOSH (2002) Hazard Review, Health Effects of Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2002-129.

- ^ "Crystalline Factsheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Silica, Crystalline". Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "If It's Silica, It's Not Just Dust!" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "What you should know about crystalline silica, silicosis, and Oregon OSHA silica rules" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ Szymendera SD (January 16, 2018). Respirable Crystalline Silica in the Workplace: New Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Standards (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- doi:10.1063/1.330062.

- .

- ^ .

- ^ Downs R. T., Palmer D. C. (1994). "The pressure behavior of a cristobalite" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 79: 9–14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- .

- .

- .

- ^ Levien L., Prewitt C. T. (1981). "High-pressure crystal structure and compressibility of coesite" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 66: 324–333. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- S2CID 129400258.

- ^ Seifertite. Mindat.org.

- S2CID 53525827.

- ISBN 978-0-7514-0480-7.

- .

- PMID 24336488.

- PMID 10911000.

- ISBN 0-471-29212-5– via Internet Archive.

External links

- Chisholm H, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Tridymite, International Chemical Safety Card 0807

- Quartz, International Chemical Safety Card 0808

- Cristobalite, International Chemical Safety Card 0809

- Amorphous, NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Crystalline, as respirable dust, NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Formation of silicon oxide layers in the semiconductor industry. LPCVD and PECVD method in comparison. Stress prevention.

- Quartz (SiO2) piezoelectric properties

- Silica (SiO2) and water

- Epidemiological evidence on the carcinogenicity of silica: factors in scientific judgement by C. Soutar and others. Institute of Occupational Medicine Research Report TM/97/09

- Scientific opinion on the health effects of airborne silica by A Pilkington and others. Institute of Occupational Medicine Research Report TM/95/08

- The toxic effects of silica Archived 2016-04-15 at the Wayback Machine by A. Seaton and others. Institute of Occupational Medicine Research Report TM/87/13

- Structure of precipitated silica