Skull and Bones

| Skull and Bones | |

|---|---|

The emblem of Skull and Bones | |

| Founded | 1832 Yale University |

| Type | Secret society |

| Scope | Local |

| Chapters | 1 |

| Members | 2,800+ lifetime |

| Nickname | Bones The Order |

| Headquarters | 64 High Street New Haven, Connecticut 06511 United States |

Skull and Bones, also known as The Order, Order 322 or The Brotherhood of Death, is an undergraduate senior secret student society at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. The oldest senior-class society at the university, Skull and Bones has become a cultural institution known for its powerful alumni and various conspiracy theories.

Skull and Bones is considered one of the "Big Three" societies at Yale University; the other are Scroll and Key and Wolf's Head.[1] The society is known informally as "Bones", and members are known as "Bonesmen", "Members of The Order" or "Initiated to The Order".[2]

History

19th century

Skull and Bones was founded in 1832 after a dispute among Yale debating societies Linonia, Brothers in Unity, and the Calliopean Society over that season's Phi Beta Kappa awards.[3] William Huntington Russell and Alphonso Taft co-founded "The Order of the Skull and Bones".[3][4] The first senior members included Russell, Taft, and thirteen other members.[5] Alternative names for Skull and Bones are The Order, Order 322 and The Brotherhood of Death.[6]

The first extended description of Skull and Bones, published in 1871 by Lyman Bagg in his book Four Years at Yale, noted that "the mystery now attending its existence forms the one great enigma which college gossip never tires of discussing."[7][8]

In a 1974 book, Brooks Mather Kelley attributed the interest in Yale senior societies to the fact that underclassmen members of then

Since its founding, Skull and Bones annually selects 15 members of the junior class to join the society.[10] Skull and Bones selects new members among students every spring as part of Yale University's "Tap Day", and has done so since 1879. It taps those that it views as campus leaders and other notable figures for its membership.

20th century

In the 1960s, secret societies adapted in response to criticism for elitism and discrimination. Skull and Bones admitted its first black member in 1965, and the president of Yale's gay student organization in 1975.[11]

Yale became coeducational in 1969, prompting some other secret societies such as St. Anthony Hall to transition to co-ed membership, yet Skull and Bones remained fully male until 1992. The Bones class of 1971's attempt to tap women for membership was opposed by Bones alumni, who dubbed them the "bad club" and quashed their attempt. "The issue", as it came to be called by Bonesmen, was debated for decades.[12]

The class of 1991 tapped seven female members for membership in the next year's class, causing conflict with the alumni association.

21st century

In recent years, Skull and Bones, like other elite Yale institutions, "utterly transformed", according to The Atlantic. The society tapped its first entirely non-white class in 2020. Few descendants of alumni get in, and progressive activism is an asset. The class of 2021 admitted no conservatives.[11]

Symbols and traditions

The society's badge is gold and consists of a skull that is supported by crossed bones, with the number 322 on the lower jaw.[10] Its members worshipped Eulogia, a fictional goddess of eloquence.[18]

The number "322" appears in Skull and Bones' insignia and is widely reported to be significant as the year of Greek orator

One legend is that the number represents "founded in '32, 2nd corps", referring to a first Corps in an unknown German university.[22][23] Another possible reference of 322 is the Freemasonic Lodge of Virtue and Silence no. 322, in Suffolk, UK, signaling a fraternal but unspoken sponsorship between the two "secret society" organizations, regarding which silence is considered virtuous. Lodge 322 was founded in 1811,[24] 21 years before the creation of the Skull and Bones association in 1832.

Crooking

Skull and Bones has a reputation for stealing keepsakes from other Yale societies or campus buildings; society members reportedly call the practice "crooking" and strive to outdo each other's "crooks".[25][26] The society has been accused of possessing the stolen skulls of Martin Van Buren, Geronimo, and Pancho Villa.[27][28][17][26] In January 2010, Christie's auctioned a human skull with links to Skull and Bones.[29]

Facilities

Tomb

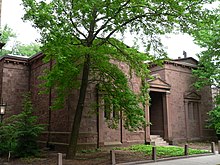

The Skull and Bones Hall, located at 64 High St. in

The architect was possibly

Deer Island

The society owns and manages Deer Island, an island retreat on the St. Lawrence River (44°21′33″N 75°54′34″W / 44.359063°N 75.909345°W). Alexandra Robbins, author of a book on Yale secret societies, wrote:

The forty-acre retreat is intended to allow Bonesmen to "get together and rekindle old friendships." A century ago the island sported tennis courts and its softball fields were surrounded by rhubarb plants and gooseberry bushes. Catboats waited on the lake. Stewards catered elegant meals."

Bonesmen spend a week in the late summer getting to know each other at Deer Island.[11]

Russell Trust Association

The Russell Trust Association is the

According to its 2016 filing with the IRS, the Russell Trust Association, filing as RTA Incorporated, has assets of $3,906,458, including Deer Island and the Skull and Bones Hall.[36]

As of 2024, the organization had an endowment of $17 million.[11]

Notable members

Skull and Bones' membership developed a reputation in association with the "

If the society had a good year, this is what the "ideal" group will consist of: a football captain; a Chairman of the

radical; a Whiffenpoof; a swimming captain; a notorious drunk with a 94 average; a film-maker; a political columnist; a religious group leader; a Chairman of the Lit; a foreigner; a ladies' man with two motorcycles; an ex-serviceman; a negro, if there are enough to go around; a guy nobody else in the group had heard of, ever ..."

Like other Yale senior societies, Skull and Bones's membership was almost exclusively limited to

Judith Ann Schiff, Chief Research Archivist at the Yale University Library, has written: "The names of its members weren't kept secret—that was an innovation of the 1970s—but its meetings and practices were."[40] While resourceful researchers could assemble member data from these sources, in 1985, Charlotte Thomson Iserbyt provided Antony C. Sutton with rosters and records that had belonged to her father, a member of the organization. This membership information was kept privately for over fifteen years, as Sutton feared that the photocopied pages could somehow identify the member who leaked it. He wrote a book on the group, America's Secret Establishment: An Introduction to the Order of Skull and Bones. The information was finally reformatted as an appendix in the book Fleshing out Skull and Bones, a compilation edited by Kris Millegan and published in 2003.

Among prominent alumni are former presidents

Members are assigned nicknames. Examples include "Long Devil", the tallest member, "Boaz", a varsity football captain, or "Sherrife", prince of the future. Many of the chosen names are drawn from literature (e.g., "

Popular culture

Literature and print

- Tom Wolfe mentions Skull and Bones in his 1976 book, The Me Decade, writing, "At Yale the students on the outside wondered for 80 years what went on inside the fabled secret senior societies, such as Skull and Bones. On Thursday nights one would see the secret society members walking silently and single file, in black flannel suits, white shirts, and black knit ties with gold pins on them, toward their great Greek Revival temples on the campus, buildings whose mystery was doubled by the fact that they had no windows."[43]

- Skull and Bones have been satirized from time to time in the George H. W. Bush, and again when the society first admitted women.[44]

- George W. Bush wrote in his autobiography, "[In my] senior year I joined Skull and Bones, a secret society; so secret, I can't say anything more."[45]

Film

- The Skulls (2000) and The Skulls II (2002) films are based on the conspiracy theories surrounding Skull and Bones.[46] A third film, The Skulls III (2004), is based on the first woman to be "tapped" to join the society.

- In The Good Shepherd (2006) the protagonist becomes a member of Skull and Bones while studying at Yale.[47]

- In Baz Luhrmann's 2013 film version of F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel The Great Gatsby, Nick Carraway calls Tom Buchanan Boaz. Tom in turn calls Nick Shakespeare. Nick said earlier that he met Tom at Yale. It is thereby implied that they were in Skull and Bones together.[26] In the novel, Yale is not explicitly mentioned (rather, they were at college in New Haven together) and it is only stated that they were in the same senior society.[48]

Television

- In Season 1, Episode 33 of the 1966

- In season 8 episode "The Canine Mutiny" (1997), after doing a secret handshakewith a dog, Mr. Burns says: "I believe this dog was in Skull and Bones".

- In Family Guy episode, "No Chris Left Behind", (2007) when Chris Griffin is being bullied by the richer students at Morningwood Academy, Lois Griffin asks her father, Carter Pewterschmidt, to help Chris. So Carter invites Chris to join Skull and Bones with the other students, who begin to accept him. As part of his initiation, Carter and Chris adopt an orphan and lock him out of the car, which is filled with toys and a puppy, and then drive away when he is unable to get in. At the initiation ceremony, Carter tells Chris that he must spend "Seven minutes in heaven" with their most senior member, Herbert. Chris feels uncomfortable about joining and convinces Carter to help him get back into his old school.

- On Meet The Press, Tim Russert asked both President George W. Bush and John Kerry about their memberships to Skull and Bones, to which the president replied, "It's so secret we can't talk about it." Kerry replied, "You trying to get rid of me here?"[50][51]

- In for-profit universities.

- In season 2 episode "New Heaven Can Wait" (2008), Chuck Bass is kidnapped by Skull and Bones members while visiting Yale. They make him pass a series of tests to assess his loyalty as they think Chuck is the ideal Skull and Bones candidate. Chuck eventually declines the offer and tricks them into performing illegal acts while filming them in order to have blackmail leverage in case he ever needs something from them in the future.

Conspiracy theories

Skull and Bones is featured in books and movies which claim that the society plays a role in a

See also

References

- ^ Jacobs, Peter (October 8, 2015). "Yale is revamping its secret society system so students don't feel left out". Business Insider. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- OCLC 2570157.

- ^ a b c "Change In Skull And Bones; Famous Yale Society Doubles Size of Its House – Addition a Duplicate of Old Building" (PDF). The New York Times. September 13, 1903. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Niarchos, Nicolas; Zapana, Victor (December 5, 2008). "Yale's secret social fabric". Yale Daily News. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ a b Richards, David (May 2015). "The Origins of the Tomb". Yale Alumni Magazine. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ Blakely, Rhys (March 2, 2013). "John Kerry and the 'Brotherhood of Death' Yale secret society". The Times. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- ^ Schiff, Judith Ann. "How the Secret Societies Got That Way". Yale Alumni Magazine (September/October 2004). Archived from the original on April 4, 2005. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- OCLC 2007757.

- ^ Yale: A History, Brooks Mather Kelley, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, Ltd.), 1974.

- ^ hdl:2027/hvd.hn4g6y– via Hathi Trust.

- ^ a b c d Horowitch, Rose (January 11, 2024). "Skull and Bones and Equity and Inclusion". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ Robbins, pp. 152–159

- ^ a b c d e Andrew Cedotal, Rattling those dry bones, Yale Daily News, April 18, 2006.

- New York Times. September 6, 1991. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- New York Times. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ New York Times. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Leuing, Rebecca (October 2, 2003). "Skull And Bones". CBS News. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Stephey, M. J. (February 23, 2009). "A Brief History of the Skull & Bones Society". Time. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009.

- ^ The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ "Letter from a member of Skull and Bones Society to another member". Yale Manuscripts & Archives Digital Images Database. Yale University Library. March 23, 1860. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- OCLC 2570157.

- ^ a b Robbins, Alexandra. Secrets of the Tomb: Skull and Bones, the Ivy League, and the Hidden Paths of Power. Back Bay Books, 2003.

- ^ "German postcard included in a Skull and Bones photograph album originally owned by Chester Wolcott Lyman, BA 1882" [Photograph albums of the Skull and Bones Society]. Yale University Library Manuscripts and Archives. 1882.

- ^ "Provincial Grand Lodge of Suffolk - Lodge of Virtue and Silence 332". www.suffolkpgl.org.uk. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ Lassila; Branch (2006). "Whose skull and bones?" (PDF). Yale Alumni Magazine: 20–22.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Landrigan, Leslie (September 17, 2018). "Skull and Bones, or 7 Fast Facts About Yale's Secret Society". New England Historical Society. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ Greenburg, Zach O. (January 23, 2004). "Bones may have Pancho Villa skull". The Yale Herald. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ISBN 1-4027-3330-5.

- ^ a b "Skull linked to secret Yale society to be sold". NBC News. January 5, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^

- ^ "Scull and Bones". Saucierflynn.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2007.

- ^ ISBN 0-316-72091-7, p. 56

- ^ a b c "Collection: Russell Trust Association Records". Archives at Yale University. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ "Skull and Bones". Britannica. August 22, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ Reynolds, Bruce L. (July 2015). "More secrets of the Tomb". Yale Alumni Magazine. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ RTS Incorporated IRS Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax, 2016. February 1, 2018. via GuideStar.

- ^ Leung, Rebecca (June 13, 2004). "Skull And Bones: Secret Yale Society Includes America's Power Elite". CBS News. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ ISBN 0-300-03330-3.

- ^ a b Karabel, Jerome (2005). The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 53–36.

- ^ Yalealumnimagazine.com Archived April 4, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Oldenburg, Don (April 4, 2004). "Bush, Kerry Share Tippy-Top Secret". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Meet the PressGoogle Video

- ^ Wolfe, Tom (August 23, 1976). "The "Me" Decade and the Third Great Awakening". New York Magazine.

- ISBN 978-1-934110-89-8.

- ISBN 0-688-17441-8.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. (July 10, 2013) The Skulls Movie Review & Film Summary (2000) | Roger Ebert. Rogerebert.suntimes.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-15.

- ^ Beaupre, Mitchell (December 22, 2021). "This Is America: How The Good Shepherd Examined the Rot at the Core of a Country". Paste Magazine. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "The Great Gatsby". Publicbookshelf.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014.

- ^ Kidd, Chip (March 2011). "Holy Eli, Batman!". Yale Alumni Magazine. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ NBC News (February 13, 2004). "Transcript for Feb. 8th". msnbc.com. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ NBC News (April 18, 2004). "Transcript for April 18". msnbc.com. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Dempsey, Rachel (January 18, 2007). "Real Elis inspired fictional 'shepherd'". Yale Daily News. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

Further reading

- ISBN 978-0470184080.

- Jarrett, William H. (2011). "Yale, Skull and Bones, and the Beginnings of Johns Hopkins". Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 24 (1). PMID 21307974.

- Klimczuk, Stephen, and ISBN 978-1402762079. pp. 212–232 ("University Secret Societies and Dueling Corps").

- Robbins, Alexandra (2003). Secrets of the Tomb: Skull and Bones, the Ivy League, and the Hidden Paths of Power. Back Bay Books. ISBN 0316735612.

- Rosenbaum, Ron (Sep. 1977). "The Last Secrets of Skull and Bones". Esquire.

- ISBN 0972020705.

- ISBN 0975290606(softcover).