List of slave owners

(Redirected from

Slave owners

)

The following is a list of notable people who owned other people as slaves, where there is a consensus of historical evidence of slave ownership, in alphabetical order by last name.

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

A

- King Abdul Aziz (1875–1953), brought his slaves to his 1945 meeting with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt,[1][2] and regulated slavery in his country in 1936.[3]

- Adelicia Acklen (1817–1887), at one time the wealthiest woman in Tennessee, she inherited 750 enslaved people from her husband, Isaac Franklin.[4]

- Stair Agnew (1757–1821), land owner, judge and political figure in New Brunswick, he enslaved people and participated in court cases testing the legality of slavery in the colony.[5]

- South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company, enslaved hundreds on his rice plantation.[6]

- William Aiken Jr. (1806–1887), 61st Governor of South Carolina, state legislator and member of the U.S. House of Representatives, recorded in the 1850 census as enslaving 878 people.[7]

- Isaac Allen (1741–1806), New Brunswick judge, he dissented in an unsuccessful 1799 case challenging slavery (R v Jones), freeing his own slaves a short time later.[8]

- Joseph R. Anderson (1813–1892), civil engineer, he enslaved hundreds to operate his Tredegar Iron Works.[9]

- John Armfield (1797–1871), Virginia co-founder of "the largest slave trading firm" in the United States, and a rapist.[10][11]

- David Rice Atchison (1807–1883), U.S. Senator from Missouri, slave owner, prominent pro-slavery activist, and violent opponent of abolitionism.[12]

- William Atherton (1742–1803), English owner of Jamaican sugar plantations.[13]

- John James Audubon (1785–1851), American naturalist. He objected to Britain's abolition of slavery in the Caribbean and bought and sold enslaved people himself.[14]

B

- Jacques Baby (1731–1789), French Canadian fur trader, slaveholder, and father of James Baby.[15]

- James Baby (1763–1833), prominent landowner, slaveholder, and official in Upper Canada.[16]

- Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), he kept several sex slaves.[17]

- Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, her foster children freed her slaves after her death.[18]

- Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475–1519), Spanish explorer and conquistador, he enslaved the indigenous people he encountered in Central America.[19]

- Emanoil Băleanu (c. 1793–1862), Wallachian politician, he enslaved Romani people on his estates.[20] In 1856 he signed a letter protesting the abolition of slavery in Wallachia.[21]

- Elizabeth Swain Bannister (c. 1785–1828), free woman of colour who owned 76 slaves in Berbice.[22]

- Hayreddin Barbarossa (1478–1546), Ottoman corsair and admiral who enslaved the population of Corfu.[23]

- William Barksdale (1821–1863), U.S. Representative and white supremacist, he enslaved 36 people by 1860 and vigorously defended the institution of slavery.[24]

- Alexander Barrow (1801–1846), U.S. Senator and Louisiana planter.[25]

- George Washington Barrow (1807–1866), Congressman and U.S. minister to Portugal, who purchased 112 enslaved people in Louisiana.[26]

- Robert Ruffin Barrow (1798–1875), American plantation owner who owned more than 450 slaves and a dozen plantations.[27]

- Lord Mayor of London. He inherited about 3,000 enslaved people from his brother Peter.[28]

- William Thomas Beckford (1760–1844), writer and collector. He inherited about 3,000 enslaved people from his father.[28]

- Benjamin Belcher (1743–1802), Nova Scotia politician and militia leader, he enslaved at least 7 people.[29]

- Saint Domingue.[30]

- Judah P. Benjamin (1811–1884), Secretary of State for the Confederate States of America, a U.S. Senator from Louisiana, and a vocal supporter of slavery.[31]

- Mexican-American War. Bent owned Charlotte and Dick Green. Charles's brother William freed the Greens after Dick fought with the posse that avenged Charles's assassination during the Taos Revolt. [32]

- Thomas H. Benton (1782–1858), American senator from Missouri.[33][34]

- George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher who purchased several enslaved Africans to work on his plantation in Rhode Island.[35]

- John M. Berrien (1781–1856), U.S. Senator from Georgia who argued that slavery "lay at the foundation of the Constitution" and that slaves "constitute the very foundation of your union".[36]

- Antoine Bestel (1766–1852), lawyer from France who migrated to Mauritius where he owned at least 122 slaves.[37][38]

- James G. Birney (1792–1857), an attorney and planter who freed his slaves and became an abolitionist.[citation needed]

- Simón Bolívar (1783–1830), wealthy slave owner who became a Latin American independence leader and eventually an abolitionist.[40]

- Governor of Illinois, he enslaved people on his farm in Monroe County.[41]

- James Bowie (c. 1796–1836), namesake of the Bowie knife, soldier at the Alamo, and slave trader.[43]

- blackbirder".[44]

- William Brattle (1706–1776), American politician and military officer, he was identified as a slave owner in a 2022 Harvard investigation into that university's legacy of slavery.[45]

- Confederate Secretary of War. He enslaved people until at least 1857.[46]

- Simone Brocard (fl. 1784), a "free colored" woman of Saint-Domingue, a slave trader, and one of the wealthiest women of that French colony.[47]

- Preston Brooks (1819–1857), veteran of the Mexican–American War and U.S. Congressman from South Carolina. A slaveholder, he beat abolitionist senator Charles Sumner nearly to death after the latter spoke against slavery in the Senate.[48]

- James Brown (1766–1835), U.S. Minister to France, U.S. Senator, and sugarcane planter, some of whose slaves were involved in the 1811 German Coast uprising in what is now Louisiana.[49]

- Chang and Eng Bunker (1811–1874), Siamese twins who became successful entertainers in the United States.[50]

- John Burbidge (c. 1718–1812), Nova Scotia soldier, land owner, judge and politician, he freed his slaves in 1790.[51]

- Pierce Butler (1744–1822), U.S. Founding Father and plantation owner.[52]

- William Orlando Butler (1791–1880), American general and politician, he advocated for gradual emancipation and enslaved people himself.[53]

C

- Julius Caesar (100–44 BCE), Roman dictator, he once sold the entire population of Atuatuci into slavery.[54] He personally owned slaves, some of whom he freed, such as Julius Zoilos.[55]

- Charles Caldwell (1772–1853), American physician who started what is now the University of Louisville School of Medicine. He defended slavery and even owned house slaves himself.[56]

- John C. Calhoun (1782–1850), 7th Vice President of the United States, owned slaves and asserted that slavery was a "positive good" rather than a "necessary evil".[57]

- Paul C. Cameron (1808–1891), North Carolina slaveholder and North Carolina Supreme Court justice. By about 1860, he owned 30,000 acres of land and 1,900 slaves.[58]

- William Capell, 4th Earl of Essex (1732–1799), he enslaved George Edward Doney as a servant.[59]

- Charles Carroll (1737–1832), signer of Declaration of Independence, enslaved approximately 300 people on his estate in Maryland.[60]

- Landon Carter (1710–1778), Virginia planter who enslaved as many as 500 people by the end of his life.[61]

- Robert "King" Carter (1663–1732), Virginia landowner and acting governor of Virginia. He left 3000 enslaved people to his heirs.[62]

- Samuel A. Cartwright (1793–1863), American physician who invented the pseudoscientific diagnosis of drapetomania to explain the desire for freedom among enslaved Africans.[63][64]

- Lewis Cass (1782–1866), American politician prominent in Michigan, was known to have owned at least one slave.[65]

- Girolamo Cassar (c. 1520 – c. 1592), Maltese architect who owned at least two slaves.[66]

- Cato the Elder (234–149 BCE), Roman statesman. Plutarch reported that he owned many slaves, purchasing the youngest captives of war.[67]

- Carlos Manuel de Céspedes (1819–1874), a Cuban revolutionary, he emancipated his own slaves at the beginning of the Ten Years' War, but only advocated for gradual abolition throughout Cuba.[68]

- Auguste Chouteau (c. 1750–1829), co-founder of the city of St. Louis, at the time of his death he owned 36 enslaved people.[69]

- Pierre Chouteau (1758–1849), half-brother of Auguste Chouteau and defendant in a freedom suit by Marguerite Scypion.[70]

- Cicero (106–43 BCE), Roman statesman and philosopher. He enslaved at least four people, but the true number is likely higher.[71]

- William Clark (1770–1838), American explorer and territorial governor, he brought one of his African-American slaves with him on the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[72]

- Nancy Clarke a Barbadian hotelier and free woman of colour.[73][further explanation needed]

- Henry Clay (1777–1852), United States Secretary of State and Speaker of the House, he advocated for gradual emancipation but owned slaves until his death.[74]

- William T. Sherman and his army.[75]

- Governor of Illinois; an abolitionist, he inherited slaves from his father and freed them.[76]

- Amaryllis Collymore (1745–1828), Barbadian slave and later slave owner and planter.[77]

- Edward Colston (1636–1711), English merchant, philanthropist and slave trader.[80]

- Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), enslaved the Taíno and Arawak people and "sent the first slaves across the Atlantic."[81]

- Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), Spanish conquistador who invaded Mexico.[82]

- Thérèse de Couagne (1697–1764), Montreal businesswoman, she enslaved Marie-Joseph Angélique who attempted to escape repeatedly.[83]

D

- Sir Robert Davers, 2nd Baronet (c. 1653–1722), English politician and landowner, he enslaved some 200 people on his plantation in Barbados.[84]

- Jefferson Davis (1807–1889), President of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. He enslaved as many as 113 people on his Mississippi plantation.[85]

Spanish Louisiana

.- Joseph Davis (1784–1870), eldest brother of Jefferson Davis and one of the wealthiest antebellum planters in Mississippi, he enslaved at least 345 people on his Hurricane Plantation.[86]

- Sam Davis (1842–1863), Confederate soldier executed by Union forces. He came from a family of slave owners and, as a child, was gifted an enslaved person.[87]

- Afro-Brazilian landowner, businessman, and nobleman. He owned several coffee plantations as well as around a thousand of slaves.[88]

- Spanish Louisiana.

- James De Lancey (1703–1760), judge and politician in colonial New York. His own slave, Othello, was accused of attending a meeting related to the Conspiracy of 1741 and De Lancey sentenced him and other suspected enslaved conspirators to death.[89]

- James De Lancey (1746–1804), colonial American and leader of a loyalist brigade. When he fled to Nova Scotia after the War of Independence, he took six enslaved people with him.[90]

- Abraham de Peyster (1657–1728), 20th mayor of New York City, he purchased two enslaved people in 1797.[91]

- Demosthenes (384–322 BCE), Athenian statesman and orator who inherited at least 14 slaves from his father.[92]

- Henry Denny Denson (c. 1715–1780), Irish-born soldier and politician in Nova Scotia, he enslaved at least five people.[93]

- 1811 German Coast Uprising.[94]

- Thomas Roderick Dew (1802–1846), president of the College of William & Mary; he was an influential pro-slavery advocate, owning one enslaved person himself.[95]

- Founding Father of the United States. Largest slaveholder in Philadelphia in 1766, he freed them in 1777.[96]

- theologian, and Princeton University professor. The 1840 US Census records Dod owning one enslaved female aged ten to twenty-four, making him one of the latest slaveholders in both Princeton and the entire state of New Jersey, which had adopted a system of gradual emancipation in 1804.[97]

- Governor of the Wisconsin Territory. In 1827, defying the Northwest Ordinance's prohibition of slavery in the territory, Dodge brought five Black slaves from Missouri to work his lead mines.[98]

- Thomas Dorland (1759–1832), Quaker, farmer and politician in Upper Canada, he enslaved as many as 20 people.[99]

- Stephen A. Douglas (1813–1861), U.S. Senator from Illinois and 1860 U.S. Democratic presidential candidate. He inherited a Mississippi plantation and 100 slaves from his father-in-law.[100] Historians continue to debate whether he opposed slavery.[101]

- Richard Duncan (died 1819), politician in Upper Canada and slave owner.[15]

- Stephen Duncan (1787–1867), originally from Pennsylvania, he became the wealthiest Southern cotton planter before the American Civil War with 14 plantations where he enslaved 2200 people.[102]

- Robley Dunglison (1798–1869), English-American physician, medical educator and author—purchased slaves from Thomas Jefferson while teaching at University of Virginia.[103]

E

- Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758), American Congregationalist theologian who played a critical role in shaping the First Great Awakening. He owned several slaves during his lifetime.[104][105]

- Governor of Illinois. He was a slave owner and evaded the Northwest Ordinance, which outlawed slavery in the territory.[106]

- Matthew Elliott (c. 1739–1814), a Loyalist, he captured slaves during the American Revolution and kept them on his farm in Upper Canada in defiance of government pressure.[107]

- George Ellis (1753–1815), English antiquary, poet and Member of Parliament, he enslaved people on his sugar plantations in Jamaica.[108]

- William Ellison (1790–1861), an African-American slave and later a slave owner.[109]

- Adrien d'Épinay (1794–1839), lawyer and politician of Mauritius.[110][111]

- Edwin Epps (born c. 1808), former overseer turned planter and, for 10 years, owner of Solomon Northup, who authored Twelve Years a Slave.[112]

F

- Mary Faber (1798–fl. 1857), Guinean slave trader known for her conflict with the West Africa Squadron.[114]

- Peter Faneuil (1700–1743), Colonial American slave trader and owner, and namesake of Boston's Faneuil Hall.[115]

- Rebecca Latimer Felton (1835–1930), suffragist, white supremacist, and Senator for Georgia, she was the last member of the U.S. Congress to have been a slave owner.[116]

- Eliza Fenwick (1767–1840), British author, she used slave labor in her Barbados schoolhouse.[117]

- Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), American statesman and philosopher, who owned as many as seven slaves before becoming a "cautious abolitionist".[118]

- Isaac Franklin (1789–1846), owner of more than 600 slaves, partner in the largest U.S. slave trading firm Franklin and Armfield, and rapist.[119]

- Nathan Bedford Forrest (1821–1877), Confederate general, slave trader, and Ku Klux Klan leader.[120]

- John Forsyth (1780–1841), congressman, senator, Secretary of State, and 33rd Governor of Georgia. He supported slavery and was a slaveholder.[121]

G

- Ana Gallum (or Nansi Wiggins; fl. 1811), was an African Senegalese slave who was freed and married the white Florida planter Don Joseph "Job" Wiggins, in 1801 succeeding in having his will, leaving her his plantation and slaves, recognized as legal.[122]

- Horatio Gates (1727–1806), American general during the American Revolutionary War. Seven years later, he sold his plantation, freed his slaves, and moved north to New York.[123]

- Sir John Gladstone (1764–1851), British politician, owner of plantations in Jamaica and Guyana, and recipient of the single largest payment from the Slave Compensation Commission.[124][125]

- Estêvão Gomes (c. 1483–1538), Portuguese explorer, in 1525 he kidnapped at least 58 indigenous people from what is now Maine or Nova Scotia, taking them to Spain where he attempted to sell them as slaves.[126]

- Antão Gonçalves (15th-century), Portuguese explorer and, in 1441, the first to enslave captive Africans and bring them to Portugal for sale.[127]

- Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885), Union general and 18th President of the United States, who acquired slaves through his wife and father-in-law.[128] On March 29, 1859, Grant freed his slave William Jones, making Jones the last person to have been enslaved by a person who later served as U.S. president.[129]

- Robert Isaac Dey Gray (c. 1772–1804), Canadian politician and slave owner. In 1798 he voted against a proposal to expand slavery in Upper Canada.[130]

- Curtis Grubb (c. 1730–1789), Pennsylvania iron master and one of the state's largest enslavers at the time of U.S. independence.[131]

H

- James Henry Hammond (1807–1864), U.S. Senator and South Carolina governor, defender of slavery, and owner of more than 300 slaves.[132]

- Wade Hampton I (c. 1752 – 1835), American general, Congressman, and planter. One of the largest slave-holders in the country, he was alleged to have conducted experiments on the people he enslaved.[133][134]

- Wade Hampton II (1791–1858), American soldier and planter with land holdings in three states. He held a total of 335 slaves in Mississippi by 1860.[135]

- Lost Cause.[136]

- John Hancock (1737–1793), American statesman. He inherited several household slaves who were eventually freed through the terms of his uncle's will; there is no evidence that he ever bought or sold slaves himself.[137]

- Benjamin Harrison IV (1693–1745), American planter and politician. Upon his death his each of his ten surviving children inherited slaves from his estate.[138]

- Benjamin Harrison V (1726–1791), American politician, United States Declaration of Independence signatory, he inherited a plantation and the people enslaved upon it from his father.[139]

- William Henry Harrison (1773–1841), 9th President of the United States, he owned eleven slaves.[140]

- Patrick Henry (1736–1799), American statesman and orator. He wrote in 1773, "I am the master of slaves of my own purchase. I am drawn along by the general inconvenience of living here without them. I will not, I cannot justify it."[141]

- U.S. Declaration of Independence. He impregnated at least one of the women he enslaved, making him the grandfather of Thomas E. Miller, one of only five African Americans elected to Congress from the South in the 1890s.[142]

- George Hibbert (1757–1837), English merchant, politician, and ship-owner. A leading member of the pro-slavery lobby, he was awarded £16,000 in compensation after Britain abolished slavery.[143]

- Thomas Hibbert (1710–1780), English merchant, he became rich from slave labor on his Jamaican plantations.[144]

- Eufrosina Hinard (born 1777), a free black woman in New Orleans, she owned slaves and leased them to others.[145]

- Thomas C. Hindman (1828–1868), American politician and Confederate general. During the Civil War he rented two enslaved families to the Medical Director of the Army of Tennessee.[146]

- Arthur William Hodge (1763–1811), British Virgin Islands planter, the first, and likely only, British subject executed for the murder of his own slave.[147]

- Jean-François Hodoul (1765–1835), captain, corsair, merchant and plantation owner who moved from France and settled in Mauritius and Seychelles.[148]

- Johns Hopkins (1795–1873), philanthropist who donated seed money for the creation of Johns Hopkins University.[149]

- Sam Houston (1793–1863), U.S. Senator, President of the Republic of Texas, 6th Governor of Tennessee, and 7th Governor of Texas; he enslaved twelve people.[150]

- thralls (slaves) rebelled and killed him.[151]

- Abijah Hunt (1762–1811), planter and merchant in the Natchez District in Mississippi. In 1808, he sold one of his plantations, complete with 60 or 61 slaves.[152]

- David Hunt (1779–1861), wealthy planter in the Natchez District of Mississippi and the largest benefactor of Oakland College, he enslaved nearly 1,700 people.[153]

- Margaret Hutton (1727–1797), largest enslaver in Pennsylvania at the time of the first federal census.[154]

I

- Ibn Battuta (1304 – c. 1368), Muslim Berber Moroccan scholar and explorer. He enslaved girls and women in his harem.[155]

- Emina Ilhamy (1858–1931), Egyptian princess, she gifted enslaved concubines to her son and owned slaves until the First World War.[156]

J

- Andrew Jackson (1767–1845), 7th President of the United States, he enslaved as many as 300 people.[157]

- William James (1791–1861), English Radical politician and owner of a West Indies plantation.[158]

- William Jarvis (1756–1817), prominent landowner and government official in York, Upper Canada.[159]

- Peter Jefferson (1708–1757), father of U.S. President Thomas Jefferson.[160] In his last will and testament he set free the slaves who remained his after paying Monticello's debts.

- Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), 3rd President of the United States. He had a long-term sexual relationship with enslaved Sally Hemings.[161]

- Thomas Jeremiah (born 1775), a free Negro executed in the Province of South Carolina for attempting to foment a slave insurrection.[162]

- Andrew Johnson (1808–1875), 17th President of the United States, he opposed the 14th Amendment (which granted citizenship to former slaves) and owned at least ten slaves before the Civil War.[163]

K

- Anna Kingsley (1793–1870), African-born, when she was thirteen Zephaniah Kingsley bought her to be his wife; she later owned slaves in her own right.[165]

- slave trader, defender of slavery and of what then was called "amalgamation", interracial marriage.[166]

- James Knight (c. 1640–c. 1721), English explorer and Hudson's Bay Company director, he enslaved indigenous women, including Thanadelthur.[167]

L

- James Ladson (1753–1812), lieutenant governor of South Carolina, he enslaved over 100 people in that state.[168]

- James H. Ladson (1795–1868), businessman and South Carolina planter.[169]

- Henry Laurens (1724–1792), 5th President of the Continental Congress, his company, Austin and Laurens, was the largest slave-trader in North America.[170]

- Delphine LaLaurie (1787–1849), New Orleans socialite and serial killer, infamous for torturing and murdering slaves in her household.[171]

- John Lamont (1782–1850), Scottish emigrant who enslaved people on his Trinidad sugar plantations.[172]

- Marie Laveau (1801–1881), Louisiana Voodoo practitioner, she enslaved at least seven people.[173]

- Fenda Lawrence (born 1742), slave trader based in Saloum. She visited the Thirteen Colonies as a free black woman.[174]

- Richard Bland Lee (1761–1827), American politician, he inherited a Virginia plantation and 29 slaves in 1787.[175]

- William Lenoir (1751–1839), American Revolutionary War officer and prominent statesman, he was the largest slave-holder in the history of Wilkes County, North Carolina.[176]

- William Ballard Lenoir (1775–1852), mill-owner and Tennessee politician, he used both paid and forced labor in his mills.[177]

- Francis Lieber (1800–1872), German-American jurist and political philosopher who authored the Lieber Code during the American Civil War. He enslaved people in South Carolina before he moved north to New York.[178][179]

- Edward Lloyd (1779–1834), American politician from Maryland, in 1832 owned 468 people, including abolitionist Frederick Douglass (then known as Frederick Bailey).[180]

- a slave named Jacob while teaching at the University of Virginia and brought him back to England, where he was listed in the census as a manservant.[182]

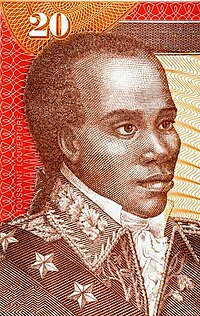

- Toussaint Louverture (1743–1803), a former slave, he enslaved a dozen people himself before becoming a general and a leader of the Haitian Revolution.[183]

- George Duncan Ludlow (1734–1808), colonial lawyer. He was a slave owner and, in 1800 as Chief Justice of New Brunswick, he supported slavery in defiance of British practice at the time.[184]

- David Lynd (c. 1745–1802), seigneur and politician in Lower Canada. He enslaved at least two people and voted against abolition in 1793.[185]

M

- James Madison (1751–1836), 4th President of the United States, by 1801 he enslaved more than 100 people on his Montpelier plantation.[186]

- James Madison Sr. (1723–1801), father of President James Madison, by the time of his death, he owned 108 slaves.[187]

- Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480–1521), Portuguese navigator, he enslaved Enrique of Malacca.[188]

- Bertrand-François Mahé de La Bourdonnais (1699–1753), naval officer and administrator of Isle de France (Mauritius) and Réunion for the French East India Company.[189][190][191]

- William Mahone (1826–1895), railroad builder, Confederate general and U.S. Senator from Virginia. He had owned slaves but joined the bi-racial Readjuster Party after the Civil War.[192]

- John Lawrence Manning (1816–1889), 65th Governor of South Carolina, in 1860 he kept more than 600 people as slaves.[193]

- Francis Marion (1732–1795), Revolutionary War general, most of the people he enslaved escaped and fought with the British.[194]

- Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, he owned between seven and sixteen household slaves at various times.[196]

- George Mason (1725–1792), Virginia planter, politician, and delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787.[197]

- Thomas Massie (burgess) (c. 1675–1731), Virginia planter and politician who served in the Virginia House of Burgesses.[198]

- William Massie (burgess) (1718–1751), Virginia planter and politician who served in the House of Burgesses. Son of burgess Thomas Massie.[198]

- Thomas Massie (Planter) (1747–1834), Virginia planter, military officer in the American Revolution, and son of burgess William Massie.[198]

- Joseph Matamata (born 1953/4), Samoan chief convicted in New Zealand of enslaving fellow Samoans.[199]

- Catharine Flood McCall (1766–1828) was one of a couple of women—like Martha Washington and Annie Henry Christian—who oversaw significant business operations that relied on slave labor in the United States in the late 1700s and early 1800s.[200]

- James McGill (1744–1813), Scottish businessman and founder of Montreal's McGill University, was a slave owner.[201]

- Henry Middleton (1717–1784), 2nd President of the Continental Congress, he enslaved about 800 people in South Carolina.[202]

- John Milledge (1757–1818), U.S. Congressman and 26th Governor of Georgia, he enslaved more than 100 people in that state.[203]

- Robert Milligan (1746–1809), Scottish merchant and ship-owner. At the time of his death, he enslaved 526 people on his Jamaica plantations.[204]

- Moctezuma II (c. 1480–1520), the last Aztec emperor; he was reported to have condemned the families of unreliable astrologers to slavery.[205]

- James Monroe (1758–1831), 5th President of the United States, he enslaved many people on his Virginia plantations.[206]

- Indro Montanelli (1909–2001), Italian journalist, historian, and writer, he bought an Eritrean child and kept her as a sex slave.[207]

- Frank A. Montgomery (1830–1903), American politician and Confederate cavalry officer.[208]

- Jackson Morton (1794–1874), Florida politician. Five men whom he enslaved attempted to escape when he threatened to move them to Alabama.[209]

- William Moultrie (1730–1805), revolutionary general and Governor of South Carolina, he enslaved more than 200 people on his plantation.[210]

- Muhammad (c. 570–632), Arab religious, social, and political leader and founder of Islam; he bought, sold, captured, and owned enslaved people and established rules to regulate and restrict slavery.[211]

- Hercules Mulligan (1740–1825), tailor and spy during the American Revolutionary War, his slave, Cato, was his accomplice in espionage.[212] After the war, Mulligan became an abolitionist.[213]

- Mansa Musa (c. 1280 – c. 1337), ruler of the Mali Empire; 12,000 slaves reportedly accompanied him on his Hajj.[214]

N

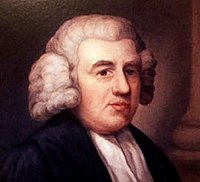

- John Newton (1725–1807), British slave trader and later abolitionist.[215]

- Nicias (c. 470–413 BCE), Athenian politician and general. Plutarch recorded that he enslaved more than 1,000 people in his silver mines.[216]

- hetaera.[217]

O

- Susannah Ostrehan (died 1809), Barbadian businesswoman, herself a freed slave, she bought some slaves (including her own family) in order to free them, but kept others to labor on her properties.[218]

- James Owen (1784–1865), American politician, planter, major-general and businessman, he owned the enslaved scholar Omar ibn Said.[219]

P

- John Page (1628–1692), Virginia merchant and agent for the slave-trading Royal African Company.[220]

- Suzanne Amomba Paillé (c. 1673–1755), African-Guianan slave, slave owner and planter.[221]

- Charles Nicholas Pallmer (1772–1848), British Member of Parliament and Jamaican plantation owner.[222]

- George Palmer (1772–1853), English businessman and politician. As a slave owner, he received compensation when slavery was abolished in Grenada.[223]

- William Penn (1644–1718), founder of Pennsylvania, he owned many slaves.[224]

- Richard Pennant, 1st Baron Penrhyn (1737–1808), owned six sugar plantations in Jamaica and was an outspoken anti-abolitionist.[225]

- John J. Pettus (1813–1867), 20th and 23rd Governor of Mississippi, enslaved 24 people on his farm.[226]

- Afro-Grenadian business woman who amassed one of the largest estates in Grenada. By the time Britain emancipated slaves in the West Indies she owned 275 slaves and was compensated 6,603 pounds sterling, one of the largest settlements in the colony.[227]

- Thomas Phillips, (1760–1851), founder of Llandovery College and a slave owner.[228]

- John Pinney (1740–1818), a British merchant, he inherited a sugar plantation on Nevis at age 22 and bought dozens of enslaved people to work it.[229][230]

- philosopher, reported to have owned several slaves.[231]

- Dutch Surinam, legendary for her cruelty.[232]

- Vedius Pollio (died 15 BCE), a Roman aristocrat remembered for being exceedingly cruel to his slaves.[233]

- James K. Polk (1795–1849), 11th President of the United States, he owned slaves most of his adult life.[234]

- Leonidas Polk (1806–1864), Episcopal bishop and Confederate general, he enslaved people on his Tennessee plantation.[235]

- Samuel Polk (1772–1827), father of President James K. Polk.[236]

- Sarah Childress Polk (1803–1891), First lady, wife of James K. Polk, one of the first female plantation owners in Tennessee.[237]

- Rachael Pringle Polgreen (1753–1791), Afro-Barbadian hotelier and brothel owner. Emancipated herself, she had a violent temper and abused her own slaves.[238]

Q

- John A. Quitman (1798–1858), Mississippi politician and prominent member of the pro-slavery Fire-Eaters.[239]

R

- Edmund Randolph (1753–1813), American statesman. Eight of his slaves were freed by the Gradual Abolition Act of 1780.[240]

- John Randolph (1773–1833), American statesman and planter, and one of the founders of the American Colonization Society.[241]

- Governor of Illinois, owned seven slaves whom he emancipated over 20 years.[242]

- George R. Reeves (1826–1882), Texas sheriff, colonel, legislator, and Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives, and was also the owner of Bass Reeves, who later became a notable lawman.[243]

- Daniel Robertson (1733–1810), British Army officer in North America, manumitted Pierre Bonga and his parents at Mackinac Island, as well as Hilaire Lamour in Montreal, but insisted that Lamour pay for the release of his wife Catherine in 1787.[244]

- William Barton Rogers (1804–1882), American scientist and founder of MIT, he enslaved at least six people, including Isabella Gibbons.[245]

- Juan Manuel de Rosas (1793–1877), Governor of Buenos Aires Province who oversaw the revival of the slave trade in Argentina.[246]

- Mary Johnston Rose (1718–1783), free person of color and hotelier on Jamaica, possibly born a slave, and later a slave owner herself.[247]

- Isaac Ross (1760–1836), Mississippi planter who stipulated in his will that his slaves be freed and moved to Africa.[248]

- Anne Rossignol (1730–1810), Afro-French slave trader.[249]

- landowner who played an important role in the creation of Harvard Law School.[250]

- Peter Russell (1733–1808), gambler, government official, politician and judge in Upper Canada.[251]

- John Rutledge (1739–1800), 2nd Chief Justice of the United States, he enslaved as many as sixty people at one time.[252]

S

- Elisabeth Samson (1715–1771), Surinamese plantation owner and daughter of a formerly enslaved woman.[253]

- Ana Joaquina dos Santos e Silva (1788–1859), Afro-Portuguese slave trader in Angola.[254]

- Ernst Heinrich von Schimmelmann (1747–1831), Danish politician and planter, he opposed the Atlantic slave trade but supported slavery, owning enslaved people in both Copenhagen and his Saint Croix plantation.[255]

- Sally Seymour (died 1824), American pastry chef and restaurateur, formerly a slave.[256][257]

- gynecology. He performed medical experiments on enslaved women whom he bought or rented.[258]

- Philip Skene (1725–1810), Scottish British army officer and New York state patroon who fought in the Saratoga campaign[259]

- University of Texas. An anti-abolitionist, he helped lead efforts to keep Texas a republic and slave state.[citation needed]

- Emilia Soares de Patrocinio (1805–1886) was a Brazilian slave, slave owner and businesswoman.[260]

- Hernando de Soto (c. 1500–1542), explorer and conquistador, he enslaved many of the indigenous people he encountered in North America. At the time of his death he owned four enslaved people.[261]

- Stephen the Great (c. 1430s–1504), Moldavian prince, he consolidated his country's practice of slavery, including the notion that different laws applied to slaves, reportedly enslaving as many as 17,000 Roma during his invasion of Wallachia.[262]

- Alexander H. Stephens (1812–1883), Vice President of the Confederate States of America and proponent for the expansion of slavery.[263]

- Charles Stewart (fl. 1740s–1770s), Scottish-American customs officer who enslaved James Somerset. In 1772, while in England, Somerset successfully sued for his freedom. The judgment in Somerset v Stewart effectively ended slavery in Britain.[264]

- J. E. B. Stuart (1833–1864), Confederate general. He and his wife enslaved two people.[265]

- John Stuart (1740–1811) was an American Anglican minister who later practiced in Kingston, Upper Canada.[266]

- Peter Stuyvesant (c. 1592–1672), director-general of New Netherland, he organized Manhattan's first slave-auction and enslaved 40 African people himself.[267]

- Thomas Sumter (1734–1832), South Carolina planter and general, in the Revolutionary War he gifted slaves to new recruits as an incentive to enlist.[268]

- Mary Surratt (1823–1865), convicted conspirator in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the first woman executed by the U.S. federal government. She and her husband were slaveholders.[269]

T

Robert Toombs (left) and one of the men he enslaved, Bishop Wesley John Gaines (right)

- Clemente Tabone (c. 1575–1665), Maltese landowner who owned at least two slaves.[270]

- Lawrence Taliaferro (1794–1871), Indian agent who enslaved Harriet Robinson and officiated her marriage to Dred Scott.[271] The largest slaveholder in what is now Minnesota, Taliaferro leased slaves to officers at Fort Snelling.[272]

- Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, as a young man he inherited slaves from his father but quickly emancipated them.[273]

- John Tayloe II (1721–1779), Virginia planter and politician, he enslaved approximately 250 people.[274]

- George Taylor (c. 1716–1781), Pennsylvania ironmaster and signer of the Declaration of Independence, he enslaved two men who, upon his death, were sold to settle his debts.[275]

- Zachary Taylor (1784–1850), 12th President of the United States, he enslaved as many as 200 people on his Cypress Grove Plantation.[276]

- Edward Telfair (1735–1807), 19th Governor of Georgia and a slave owner.[277]

- Thomas Thistlewood (1721–1786), British planter in Jamaica, he recorded torturing and raping slaves in his diary.[278]

- George Henry Thomas (1816–1870), Union General in the American Civil War, he owned slaves during much of his life.[279]

- Madam Tinubu (1810–1887), Nigerian aristocrat and slave trader.[280]

- Tippu Tip (1832–1905), Zanzabari slave trader.[281]

- Tiradentes (1746–1792), Brazilian revolutionary.[282]

- Alex Tizon (1959–2017), Pulitzer Prize winner and author of "My Family's Slave".[283]

- Confederate Secretary of State, and brigadier general in the Confederate Army. He owned many slaves on his plantations, including Garland H. White, William Gaines and Wesley John Gaines.[284]

- George Trenholm (1807–1876), American financier, he enslaved hundreds of people on his plantations and in his household.[285]

- Homaidan Al-Turki (born 1969), Colorado resident convicted in 2006 of enslaving and abusing his housekeeper.[286]

- John Tyler (1790–1862), 10th President of the United States, was 23 when he inherited his father's Virginia plantation and 13 slaves.[287]

U

- Umayya ibn Khalaf (died 624), Arab slaveholder and tribal leader who enslaved Bilal ibn Rabah

V

- Martin Van Buren (1782–1862), 8th President of the United States and later a vocal abolitionist, owned at least one enslaved person and apparently leased others while he lived in Washington.[288]

- Joseph H. Vann (1798–1844), Cherokee leader with hundreds of slaves in Indian Territory.[289]

- Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), Spanish painter, he enslaved Juan de Pareja who was his assistant and a notable painter himself.[290]

- Amerigo Vespucci (1451–1512), Italian explorer and eponym of America, his estate held five slaves at his death.[291]

- Jacques Villeré (1761–1830), Governor of Louisiana. 53 people he had enslaved were liberated by the British after the Battle of New Orleans.[292]

- Elisabeth Dieudonné Vincent (1798–1883), a Haitian-born free businesswoman of color who, along with her husband, owned slaves in New Orleans.[293]

W

- Walkara (ca. 1805-1855), leader in the Timpanogos Native American group in what is now Utah, enslaved other Native Americans (typically Paiute or Goshute) many of whom he traded to California or New Mexico.[294][295][296]

- Joshua John Ward (1800–1853), Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina and "the king of the rice planters", whose estate was once the largest slaveholder in the United States (1,130 slaves).[297]

- Augustine Washington (1694–1743), father of George Washington. At the time of his death he owned 64 people.[300]

- George Washington (1732–1799), 1st President of the United States, who owned as many as 300 people.[301] In his last will and testament he set all his slaves free.

- Martha Washington (1731–1802), 1st U.S. First Lady, inherited slaves upon the death of her first husband and later gave slaves to her grandchildren as wedding gifts.[302]

- John Wayles (1715–1773), English slave trader and father-in-law of Thomas Jefferson.[303]

- Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court who owned slaves and had three children by an enslaved woman.[304]

- Governor of Alabama and slave owner.[305]

- John Wedderburn of Ballindean (1729–1803), Scottish landowner whose slave, Joseph Knight, successfully sued for his freedom.[306]

- Richard Wenman (c. 1712–1781). Nova Scotia politician and brewer. One of his slaves, Cato, attempted to escape in 1778.[307]

- John H. Wheeler (1806–1882), U.S. Cabinet official and North Carolina planter. In separate, well-publicized incidents, two women he enslaved, Jane Johnson and Hannah Bond, escaped from him and both gained their freedom.[308][309]

- William Whipple (1730–1785), American general and politician, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and slave trader.[310]

- George Whitefield (1714–1770), English Methodist preacher who successfully campaigned to legalize slavery in Georgia.[311]

- James Matthew Whyte (c. 1788–1843), Canadian banker, he enslaved at least a dozen people on a plantation in Jamaica.[312]

- James Beckford Wildman (1789–1867), English MP and owner of Jamaican plantations.[313]

- John Witherspoon (1723–1794), Scottish-American Presbyterian minister, Founding Father of the United States, president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). At the time of his death, he owned "two slaves...valued at a hundred dollars each".[314]

- Pequot people.[315]

- Joseph Wragg (1698–1751), British-American merchant and politician. He and his partner Benjamin Savage were among the first colonial merchants and ship owners to specialize in the slave trade.[316]

- Wynflaed (died c. 950/960), an Anglo-Saxon noblewoman, she bequeathed a male cook named Aelfsige to her granddaughter Eadgifu.[317][318]

- George Wythe (1726–1807), American legal scholar, U.S. Declaration of Independence signatory. He freed his slaves late in his life.[319]

Y

- William Lowndes Yancey (1814–1863), American secessionist leader, he was gifted 36 people as a dowry and established a plantation where he forced them to work.[320]

- Marie-Marguerite d'Youville (1701–1771), the first person born in Canada to be declared a saint and "one of Montreal's more prominent slaveholders".[321]

- David Levy Yulee (1810–1886), American politician and attorney, he forced enslaved people to work his Florida sugarcane plantation and later to build a railroad.[322]

Z

- Juan de Zaldívar (1514–1570), Spanish official and explorer, he enslaved many people on his farms and mines in New Spain.[323]

See also

- List of presidents of the United States who owned slaves

- List of slaves

- Slavery among the indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Bibliography of slavery in the United States

References

- ISBN 9780815737162. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

Ibn Saud had come from Jidda on an American destroyer, the USS Murphy, with an entourage of bodyguards, cooks, and slaves

- Washington Post. Archived from the originalon 18 March 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

During the four-hour meeting between the President and the King, where the two discussed oil, Palestinian territories and their future partnership, "7-foot tall Nubian slaves" could be found on the opposite deck of the destroyer

- ISSN 1943-6149. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

1936, the same year in which King Abd al Aziz ibn Abd ar Rahman Al Saud (r. 1902-53) decreed the Saudi Arabian slave regulations

- ^ James A. Hoobler, Sarah Hunter Marks, Nashville: From the Collection of Carl and Otto Giers, Arcadia Publishing, 2000, p. 36

- ^ "Biography – Agnew, Stair – Volume VI (1821–1835) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca.

- ^ Bigner, Melissa (February 2012). "Living History". Charleston Magazine.

- JSTOR 3514348.

- ^ Spray, W.A. (1979–2016). "Jones, Caleb". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Bumgardner, Sarah (29 November 1995). "Tredegar Iron Works: A Synecdoche for Industrialized Antebellum Richmond". Antebellum Richmond. Archived from the original on 8 September 2008.

- JSTOR 42627764.

- Washington Post. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ISBN 978-0140125184pp. 145–148

- ISBN 976-8007141.

- OCLC 1330888409.

- ^ ISBN 1895258057.

- ^ "An act to prevent the further introduction of slaves". Upper Canada History. 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ Warrick, Joby (27 October 2019). "Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, extremist leader of Islamic State, dies at 48". The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

Later, former hostages would reveal that Mr. Baghdadi also kept a number of personal sex slaves during his years as the Islamic State's leader

- ^ Zuiderweg, Adrienne (13 January 2014). "Bake, Adriana Johanna (1724–1787)". Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ Keen, Benjamin (8 January 2021). "Vasco Núñez de Balboa". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Elena D. Gheorghe, Gabriel Stegărescu, "Monografia comunei Bolintinul din Deal", in Sud. Revistă Editată de Asociația pentru Cultură și Tradiție Istorică Bolintineanu, Issues 1–2/2013, pp. 29–30

- OCLC 7270251

- ^ "Elizabeth Swain Bannister". Legacies of British Slave-ownership. London: University College London. 2020. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ "Δήμος Κέρκυρας – Δεύτερη Ενετοκρατία". www.corfu.gr.

- ^ McKee, James W. (13 April 2018). "William Barksdale". Mississippi Encyclopedia. Center for Study of Southern Culture. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "The Diary of Bennet H. Barrow, Louisiana Slaveowner". www.sjsu.edu. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ "Bill of sale from the heirs of Jesse Batey to Washington Barrow, January 18, 1853 · Georgetown Slavery Archive". slaveryarchive.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Frost, Amy (2007), "Big Spenders: The Beckford's and Slavery", BBC

- ^ Elliott, Shirley B. (1979–2016). "Belcher, Benjamin". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Stewart R. King: Blue Coat Or Powdered Wig: Free People of Color in Pre-revolutionary Saint Domingue

- JSTOR 29777899.

- ^ Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society. Kansas State Historical Society. 1923. p. 61.

- JSTOR 1842457

- ISBN 978-1610753029, retrieved 13 January 2013

- ^ Humphreys, Joe (18 June 2020). "What to do about George Berkeley, Trinity figurehead and slave owner?". The Irish Times. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War and Reconstruction; by Allen C. Guelzo, May 18, 2012, kindle location 935

- ^ "Mauritius 5132 Claim". University College London (Dept. of History) Legacies of British Slavery. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Mauritius 6950 Claim". University College London (Dept. of History) Legacies of British Slavery. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "James Blair: Profile & Legacies Summary". Legacies of British Slave-ownership. UCL Department of History. 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ Manrique, Jaime (26 March 2006). "Simon Bolivar's extreme makeover". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Hanabarger, Linda (13 July 2010). "The story of Illinois' first governor". The Leader-Union. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Coté, André (1979–2016). "Marie". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ISBN 0890158819.

- ^ Storrar, Krissy (4 April 2021). "The first 'blackbirder:' Rebranding for Australian village named after Scottish slave trader". The Sunday Post. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Hartocollis, Anemona (26 April 2022). "Harvard Details Its Ties to Slavery and Its Plans for Redress". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ISBN 0813191653.

- ISBN 978-0253210432.

- ^ Puleo, Stephen. "Charles Sumner and Preston Brooks". Bill of Rights Institute. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-1445695310.

- ISBN 978-1469618302

- ^ Dunlop, Allan C. (1979–2016). "Burbridge, John". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ "Butler Family". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-1621901181.

- ISSN 1755-6058.

- ISBN 978-0500771709.

- S2CID 145124720.

- ^ Wilson, Clyde N. (26 June 2014). "John C. Calhoun and Slavery as a 'Positive Good': What He Said". The Abbeville Institute. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ISSN 2769-0806. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Watford's slavery past discovered". Watford Observer. 23 March 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ISBN 978-0385152068.

- ISBN 0801435218.

- ^ Carlton, Florence Tyler (1982). A Genealogy of the Known Descendants of Robert Carter of Corotoman.

- ISBN 0761964002.

- ^ Pilgrim, David (November 2005). "Question of the Month: Drapetomania". Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-8733-8536-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mangion, Giovanni (1973). "Girolamo Cassar Architetto maltese del cinquecento" (PDF). Melita Historica (in Italian). 6 (2). Malta Historical Society: 192–200. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2016.

- ^ Plutarch's Lives of Illustrious Men. Vol. 1. Translated by Langhorne, John; Langhorne, William. London: Henry G. Bohn. 1853. p. 389.

- ISBN 978-1469617329.

- ^ "National Park Service". Archived from the original on 22 April 2010.

- ^ William E. Foley, "Slave Freedom Suits before Dred Scott: The Case of Marie Jean Scypion's Descendants", Missouri Historical Review, 79, no. 1 (October 1984), pp. 1–5, at The State Historical Society of Missouri, accessed 18 February 2011

- S2CID 163283620. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ "Lewis and Clark . Inside the Corps . York". PBS.

- ^ Welch 1999.

- ^ "History, Travel, Arts, Science, People, Places". Smithsonian.

- ISBN 978-0684845029. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Coles, Edward. "Autobiography." April 1844. Coles Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- ISSN 0196-1373. Archived from the originalon 10 November 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ISBN 978-1608700417.

- ISBN 978-0807114322.

- required.)

- ^ Loewen, James W. (1995). Lies My Teacher Told Me. The New Press. pp. 57–58.

- ^ Jane Landers, Slaves, Subjects, and Subversives: Blacks in Colonial Latin America, UNM Press, 2006, p. 43

- ^ Lachance, André (1979–2016). "Couagne, Thérèse de". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ "Suffolk and the slave trade". www.bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ISBN 0060168366.

- ^ Lasswell Crist, Lynda (February 2016). "Joseph Emory Davis: A Mississippi Planter Patriarch". Mississippi History Now. Mississippi Historical Society. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ DeGennaro, Nancy. "Confederate monuments: Sam Davis, a slave-owning soldier mythologized as a 'Boy Hero'". The Daily News Journal. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Lopes, Marcus (15 July 2018). "A história esquecida do 1º barão negro do Brasil Império, senhor de mil escravos". BBC News. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ISBN 978-1493008407.

- ^ Moody, Barry M. (1979–2016). "DeLancey (de Lancey, De Lancey, Delancey), James". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Fellows, Jo-Ann (1979–2016). "De Peyster, Abraham". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Demosthenes, Against Aphobus 1, 6. Archived 20 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bumsted, J. M. (1979–2016). "Denson, Henry Denny". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ "Jean Noël Destrehan" by John H. Lawrence, KnowLouisiana.org Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Ed. David Johnson. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, 18 Jun 2013. Web. 15 Apr 2017.

- ^ Ely, Melvin Patrick; Loux, Jennifer R. (12 February 2021). "Dew, Thomas R. (1802–1846)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ISBN 978-0195304510.

- ^ Mack, Jessica R. "Albert Dod". Princeton & Slavery. The Trustees of Princeton University. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ "Redfearn, Winifred V. "Slavery in Wisconsin" Wisconsin 101: Our History in Objects September 11, 2018".

- ^ Fraser, Robert Lochiel (1979–2016). "Dorland, Thomas". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ "Stephen A. Douglas and the American Union, University of Chicago Library Special Exhibit, 1994". Lib.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- JSTOR 1902683.

- ^ Brazy, Martha Jane (19 April 2018). "Stephen Duncan". Mississippi Encyclopedia. Center for Study of Southern Culture. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Schulman, Gayle M. "Slaves at the University of Virginia" (PDF). www.latinamericanstudies.org. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ISBN 978-0830879410.

...they owned several slaves. Beginning in June 1731, Edwards joined the slave trade, buying 'a Negro Girle named Venus ages Fourteen years or thereabout' in Newport, at an auction, for 'the Sum of Eighty pounds.'

- ^ Stinson, Susan (5 April 2012). "The Other Side of the Paper: Jonathan Edwards as Slave-Owner". Valley Advocate. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ McClellan McAndrew, Tara (12 January 2017). "Slavery in the Land of Lincoln". Illinois Times.

- S2CID 149992126.

- ^ Higman, Montpelier (Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 1998), pp. 20, 24.

- ^ Larry Koger, Black Slaveowners: Free Black Slave Masters in South Carolina, 1790–1860, University of South Carolina Press, 1985 (paperback edition, 1995), pp. 144–145

- ^ "Mauritius 5696 Claim 16th Jan 1837 103 Enslaved £3194 15s 6d". University College London. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Mauritius 3901 A Claim 31st Jul 1837 332 Enslaved £10757 2s 0d". University College London. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Calautti, Katie (2 March 2014). ""What'll Become of Me?" Finding the Real Patsey of 12 Years a Slave". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Theuws, De Jong and van Rhijn, Topographies of Power, p. 255.

- ^ Mouser, Bruce L. (17 October 1980). "Women Traders and Big-Men of Guinea-Conakry" (PDF). tubmaninstitute.ca. Tubman Institute. pp. 6–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ "Peter Faneuil and Slavery". Boston African American National Historic Site. National Park Service. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ISBN 978-0762764396.

- ISBN 978-1442206991.

- ^ Nash, Gary B. "Franklin and Slavery." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 150, no. 4 (2006): 620.

- ^ Betsy Phillips (7 May 2015). "Isaac Franklin's money had a major influence on modern-day Nashville — despite the blood on it". Nashville Scene. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ISBN 978-0762774883.

- ISBN 978-0821419342.

- ^ Jane Landers, Black Society in Spanish Florida

- ^ Mellen, G. W. F. (1841). An Argument on the Unconstitutionality of Slavery. Saxton & Peirce. pp. 47–48.

- ^ Michael Craton, "Proto-peasant revolts? The late slave rebellions in the British West Indies 1816–1832." Past & Present 85 (1979): 99–125 online.

- ^ "Britain's Forgotten Slave Owners, Profit and Loss". BBC Two. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Vigneras, L.A. (1979–2016). "Gomes, Estêvão". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ISBN 978-8522503889.

- ISBN 0684849275.

- ^ "William Jones (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Burns, Robert J. (1979–2016). "Gray, Robert Isaac Dey". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ISBN 978-1501722196.

- ^ Brown, Rosellen (29 January 1989). "Monster of All He Surveyed". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~msissaq2/hampton.html The Wade Hampton Family, The Issaquena Genealogy and History Project, Rootsweb, retrieved May 7, 2017

- ^ American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, p. 29, retrieved 27 May 2020

- ^ "Wade Hampton Family", Issaquena Genealogy and History Project, Rootsweb, accessed 6 November 2013

- ^ Demer, Lisa (2 July 2015). "Wade Hampton no more: Alaska census area named for confederate officer gets new moniker". Alaska Dispatch News. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ISBN 0395276195.

- ISBN 978-160021-0662.

- ^ Dowdey, Clifford (1957). The Great Plantation. New York: Rinehart & Co. p. 162.

- ^ Whitney, Gleaves, "Slaveholding Presidents" (2006). Ask Gleaves. Paper 30. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ask_gleaves/30

- ISBN 978-1439190814.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (8 April 2018). "Final member of a generation of Southern black lawmakers dies, April 8, 1938". Politico. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Source: Slavery Abolition Act (P.P. 1837–8, XLVIII); NA, Treasury Papers, slave compensation T71/852-900. – referenced in Draper, N. (2008). "The City of London and slavery: evidence from the first dock companies, 1795–1800". Economic History Review, 61, 2 (2008), pp.432–466.

- ^ "Hibbert, George (1757–1837), of Clapham, Surr". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ISBN 978-1573245531.

- ISBN 978-0865545564.

- ISBN 978-0738819310.

- ^ "Compensation claim 6147". Legacies of Slavery UCL. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Noted abolitionist Johns Hopkins owned slave".

- ^ Krystyniak, Frank (20 July 2018). "Houston, the Emancipator". Today@Sam. Sam Houston State University. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Hjörleifshöfði". brydebud.vik.is. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ISBN 978-1604730500. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ISBN 978-0807118603.

- ^ United States Bureau of the Census (1909). A Century of Population Growth from the First Census of the United States to the Twelfth, 1790–1900. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 137.

- ISBN 978-1101127018.

- ISBN 978-0-791-48707-5.

- ^ "Andrew Jackson's Enslaved Laborers". The Hermitage. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ "William James MP: Profile & Legacies Summary". Legacies of British Slave-ownership. UCL Department of History 2014. 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^

"Henry Lewis: seeking freedom". Archives of Ontario. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

Hannah Jarvis incorrectly wrote about the Slave Act that Simcoe... 'has by a piece of chacanery freed all the negroes...'

- ^ Verell, Nancy (14 April 2015). "Peter Jefferson". www.monticello.org. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Stockman, Farah (16 June 2018). "Monticello Is Done Avoiding Jefferson's Relationship With Sally Hemings". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ISBN 978-0300152142p. 2.

- ^ "Slaves of Andrew Johnson". Andrew Johnson. National Park Service. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Silverman, Jason H. (1979–2016). "King, William". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ISBN 0813026164.

- ISBN 978-0813044620.

- ^ Dodge, Ernest S. (1979–2016). "Knight, James". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ We the People: The Economic Origins of the Constitution

- ^ The history of Georgetown County, South Carolina, p. 297 and p. 525, University of South Carolina Press, 1970

- ^ "Slavery and Justice: Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice" (PDF). Brown University. October 2006.

- ISBN 978-0813038063.

- ^ Lamont, John (21 March 2017). "Summary of Individual". Legacies of British Slave-ownership. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ Carolyn Morrow Long: A New Orleans Voudou Priestess: The Legend and Reality of Marie Laveau, 2018

- ISBN 978-0253217493.

- ^ "Sully Historic Site History". Fairfax County, Virginia. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Storrow, Emily (18 March 2015). "Griffin: Slave owners here no more benevolent than others". Wilkes Journal-Patriot.

- ^ Gail Guymon, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for Lenoir Cotton Mill Warehouse, February 2006. Retrieved: 2009-11-03.

- ^ "A Tale of Two Columbias: Francis Lieber, Columbia University and Slavery | Columbia University and Slavery". columbiaandslavery.columbia.edu. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- S2CID 254496072.

- Yahoo News. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16964. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ Gayle M. Schulman (2005). "Slaves at the University of Virginia" (PDF). Latin American Studies. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

Soon after he arrived from England George Long acquired a slave, Jacob.

- ^ de Cauna, Jacques. 2004. Toussaint L'Ouverture et l'indépendance d'Haïti. Témoignages pour une commémoration. Paris: Ed. Karthala. pp. 63–65

- ^ Wallace, C.M. (1979–2016). "Ludlow, George Duncan". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Morel, André (1979–2016). "Lynd, David". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ISBN 978-0807835302.

- ^ Taylor, Elizabeth Dowling. (Jan. 2012), A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons, Foreword by Annette Gordon-Reed, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, Chapter 1

- ^ Singapore, National Library Board. "Purbawara Panglima Awang – BookSG – National Library Board, Singapore". eresources.nlb.gov.sg. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ISBN 978-2869786806.

- ^ "Truth and Justice Commission Report Vol. 1" (PDF). Government of Mauritius. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ISBN 978-0822333999. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Luebke, Peter C. (12 February 2021). "Mahone, William (1826–1895)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "American slave owners". Geni. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Young, Jeffrey Robert. Domesticating Slavery: The Master Class in Georgia and South Carolina, 1670–1837. University of North Carolina Press, 1999, p. 93

- .

Marryat, Joseph (1757–1824), West Indian slave owner, ship owner, and politician ... An inheritance of £2000 from an uncle enabled him to set up as a merchant and to invest over time in plantations and enslaved people in Trinidad, Grenada, Jamaica, and St Lucia. ... At the time of emancipation his sons Joseph Marryat (1790–1876) and Charles Marryat (1803–1884), who had taken on the merchant house, received compensation of over £40,000 for 700 enslaved men and women in Trinidad, Jamaica, St Lucia, and Grenada.

- ISBN 978-1594488238.

- ^

Copeland, Pamela C.; MacMaster, Richard K. (1975). The Five George Masons: Patriots and Planters of Virginia and Maryland. University Press of Virginia. p. 162. ISBN 0813905508.

- ^ a b c "Massie family papers, 1766–1920s - Archives & Manuscripts at Duke University Libraries". David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- ^ Hollingsworth, Julia (29 July 2020). "Samoan chief in New Zealand sentenced to 11 years in jail for slavery but experts say he is just the tip of the iceberg". CNN. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ Ambuske, Jim. Accounting for Women in the Business of Slavery with Alexi Garrett (Audio). Mount Vernon.

- ^ Everett-Green, Robert (12 May 2018). "200 Years a Slave: The Dark History of Captivity in Canada". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Van Deusen, John G. (1961). "Middleton, Henry". Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. 6 (revised ed.). New York: Scribner's. p. 600.

- JSTOR 274780.

- ^ "1811 Jamaica Almanac – Clarendon Slave-owners". Jamaicanfamilysearch.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ISBN 978-0195330830.

- ^ Gawalt, Gerard W. (1993). "James Monroe, Presidential Planter". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 101 (2): 251–272.

- ^ "Statue of famous Italian journalist defaced in Milan". Al Jazeera. 15 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- OL 6909271M.

- ^ Clavin, Matthew (1 January 2016). "When Florida Men Overcame Our Racists". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Slavery through the Eyes of Revolutionary Generals". 7 November 2017.

- ^ "Slavery in Islam". British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ISBN 978-0553383294. p. 226.

- ISBN 978-0143034759. Originally published New York, Penguin Press, 2004. p. 214.

- ^ de Graft-Johnson, John Coleman, "Mūsā I of Mali" Archived 2017-04-21 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica, 15 November 2017.

- ^ Hochschild, Adam (2005), Bury the Chains, The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery, Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, p. 77

- ^ Plutarch, The Lives, "Nicias"

- ISBN 978-1405188050.

- ^ Candlin, Kit; Pybus, Cassandra (2015). "A Lasting Testament of Gratitude: Susannah Ostrehan and her nieces". Enterprising Women: Gender, Race, and Power in the Revolutionary Atlantic. University of Georgia Press. pp. 83, 89.

- ^ Hunwick, John O. (2004). "I Wish to be Seen in Our Land Called Afrika: Umar b. Sayyid's Appeal to be Released from Slavery (1819)" (PDF). Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 5.

- ^ "Plantation Life & Slavery". The Rosewell Foundation. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ Régnier, Louis-Ferdinand (March 2010). "Suzanne Amomba Paillé, une femme guyanaise". Blada (in French). French Guiana. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ISBN 978-0521193146. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "George Palmer: Profile & Legacies Summary". Legacies of British Slave-ownership. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Avery, Ron (20 December 2010). "Slavery stained some unlikely founders, too". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ "Penrhyn Castle Slavery | The Pennants". www.spanglefish.com.

- ^ Garraty, John A.; Carnes, Mark C., eds. (1999). American National Biography. Vol. 17. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 414–415 – via American Council of Learned Societies.

- ^ Candlin, Kit; Pybus, Cassandra (2015). Enterprising Women: Gender, Race, and Power in the Revolutionary Atlantic. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-4455-3.

- ^ "Summary of Individual | Legacies of British Slave-ownership". www.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ Pares, Richard (1950). A West India Fortune. Longmans Green & Co.

- ^ "The Mountravers Plantation Community, 1734 to 1834". Mountravers Plantation (Pinney's Estate) Nevis, West Indies. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Laërtius, Diogenes. Lives of the Eminent Philosophers.

- ISBN 978-9004253704.

- ^ Dio 52.23.2; Pliny the Elder, Natural History 9.39; Seneca the Younger, On Clemency 1.18.2.

- ISBN 978-0195157352.

- ISBN 978-0393047585.

- ^ Kinslow, Zacharie W. "Enslaved and Entrenched: The Complex Life of Elias Polk". White House Historical Association. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Greenberg, Amy (2019). Lady First: The World of First Lady Sarah Polk. Knopf.

- Project MUSE.

- ISBN 978-0807141519.

- ^ Lawler, Edward Jr. "Washington, the Enslaved, and the 1780 Law". The President's House, Philadelphia. USHistory.org. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ David Lodge, "John Randolph and His Slaves", Shelby County History, 1998, accessed 15 March 2011

- ^ Klickna, Cinda (2003). "Slavery in Illinois". Illinois Heritage. Illinois Periodicals Online.

- ISBN 978-0803205413.

- ISBN 978-0773535787.

- ^ Peter Dizikes (12 February 2018). "MIT class reveals, explores Institute's connections to slavery". MIT News Office. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ISBN 0842028978.

- . Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ Dale Edwyna Smith, The Slaves of Liberty: Freedom in Amite County, Mississippi, 1820–1868, Routledge, 2013, pp. 15–21

- ^ Stewart R. King: Blue Coat Or Powdered Wig: Free People of Color in Pre-revolutionary Saint Domingue

- ^ "The Royalls". Royall House & Slave Quarters. 2 October 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 41: A Sketch of Russell Abbey". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Revisited.

- ^ "Intellectual Founders – Slavery at South Carolina College, 1801–1865". University of South Carolina Libraries. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ISBN 978-0199935802. – via Oxford University Press's Reference Online (subscription required)

- ^ Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong, Dictionary of African Biography, Volym 1–6

- ^ Bregnsbo, Michael. "Ernst Schimmelmann". Den Store Danske, Gyldendal. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Amrita Chakrabarti Myers, Forging Freedom: Black Women and the Pursuit of Liberty in Antebellum Charleston

- ^ David S. Shields, The Culinarians: Lives and Careers from the First Age of American Fine Dining

- ^ Wylie, W. Gill (1884). Memorial Sketch of the Life of J. Marion Sims. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- ^ Papers of the New Haven Colony Historical Society, Volume 6, Tuttle, Morehouse, and Taylor: New Haven, 1900, "Negro Governors", Orville Platt, pp. 327–9

- ^ Franklin W. Knight and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Dictionary of Caribbean and Afro–Latin American Biography, Oxford University Press, 2016

- ^ Davidson, James West. After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection Volume 1. McGraw Hill, New York 2010, Chapter 1, p. 3

- ISBN 963-9241-84-9.

- ISBN 978-0807140963.

- ^ Blumrosen, Alfred W. & Blumrosen, Ruth G. Slave Nation: How Slavery United the Colonies and Sparked the American Revolution. Sourcebooks, 2005.

- ISBN 978-0743278195.

- ^ John Stuart – Dictionary of Canadian Biography Retrieved 2015-04-07

- ^ "The Case Against Peter Stuyvesant". New York Almanack. 16 December 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Smith, Stephen D. (12 October 2016). "African Americans in the Revolutionary War". South Carolina Encyclopedia. University of South Carolina, Institute for Southern Studies. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ISBN 978-0465038152

- ^ Bugeja, Anton (2014). "Clemente Tabone: The man, his family and the early years of St Clement's Chapel" (PDF). The Turkish Raid of 1614: 42–57. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018.

- ISBN 978-0195301731.

- ^ "Enslaved African Americans and the Fight for Freedom". Historic Fort Snelling – Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. Retrieved May 28, 2009 from New Advent.

- ISBN 978-0521782494. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Whelan, Frank (15 June 1984). "George Taylor: A Historical Perspective Founding Father's Patriotic Beliefs Cost Him Everything". The Morning Call. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- The Ouachita Citizen, August 6, 2014

- ^ Edward Telfair Papers, 1764–1831; 906 Items & 5 Volumes; Savannah, Georgia; "Papers of a merchant, governor of Georgia, and delegate to the Continental Congress".

- ISBN 0333480309

- ISBN 978-0806138671.

- ^ "Madam Tinubu: Inside the political and business empire of a 19th century heroine". The Nation. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Sheriff, Abdul (1987). Slaves, Spices & Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Commercial Empire into the World Economy, 1770–1873. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. p. 108.

- ^ "São João del-Rei On-Line / Celebridades / Joaquim José da Silva Xavier". www.sjdr.com.br. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "'Disgusted' Women, Minorities Criticize Viral Atlantic Story 'My Family's Slave'". Observer. 16 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ "Jackson Chapel to celebrate 150 years in special service with Bishop Jackson – www.news-reporter.com – News-Reporter".

- ^ Betty Myers (August 1973). "Annandale Plantation" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places – Nomination and Inventory. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "Saudi linguist gets reduced sentence in sex slave case". KDVR. Centennial, Colo. 25 February 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ISBN 978-0807830413.

- ^ Costello, Matthew (27 November 2019). "The Enslaved Households of President Martin Van Buren". The Whitehouse Historical Association. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ Williamson, N. Michelle (21 November 2013). "Joseph Vann (1798–1844)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- OCLC 555658364.

- ^ Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2007). Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America. New York: Random House. pp. 178–180.

- ISBN 978-1107133716.

- ISBN 978-0674065161.

- ^ Ronald L. Holt. Beneath These Red Cliffs. USU Press. p. 25.

- ^ Larson, Gustive O. "Walkara's Half Century". Western Humanities Review; Salt Lake City Vol. 6, Iss. 3, (Summer 1952): 235.

- ^ Williams, Don B (2004). Slavery in Utah Territory: 1847-1865. Mt Zion Books, ISBN 0974607622

- ^ The Sixteen Largest American Slaveholders from 1860 Slave Census Schedules Archived 2013-07-19 at the Wayback Machine, Transcribed by Tom Blake, April to July 2001, (updated October, 2001 and December 2004 – now includes 19 holders)

- ^ "United States Census (Slave Schedule), 1850". FamilySearch. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ISBN 978-0814794555.

- ^ "Slavery at Popes Creek Plantation", George Washington Birthplace National Monument, National Park Service, accessed April 15, 2009

- ^ "The Net Worth of the American Presidents: Washington to Trump". 24/7 Wall St. 247wallst.com. 10 November 2016. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ "Martha Washington & Slavery". George Washington's Mount Vernon: Digital Encyclopedia. Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. 2015. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ISBN 978-1442239845.

- ^ Henningson, Trip. "James Moore Wayne". Princeton and Slavery. Princeton University. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ McKiven, Henry M. Jr. (30 September 2014). "Thomas Hill Watts (1863–65)". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Alabama Humanities Foundation. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ National Archives of Scotland website feature – Slavery, freedom or perpetual servitude? – the Joseph Knight case Retrieved May 2012

- ^ Fingard, Judith (1979–2016). "Wenman, Richard". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ "The Liberation of Jane Johnson", One Book, One Philadelphia, story behind The Price of a Child, The Library Company of Philadelphia, accessed 2 March 2014

- ^ Bosman, Julie (18 September 2013). "Professor Says He Has Solved a Mystery Over a Slave's Novel". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Vaughan, Dorothy Mansfield (26 February 1964). "This Was a Man: A Biography of General William Whipple". New Hampshire: The National Society of The Colonial Dames in the State of New Hampshire. Archived from the original on 18 January 2003. Retrieved 18 January 2003.

- ISBN 978-1433513411.

- ^ Burley, David G. (1979–2016). "Whyte, James Matthew". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Great Britain Committee on Slavery (1833), "Select Committee on the Extinction of Slavery Throughout the British Dominions, Report", J. Haddon.

- ^ Knowlton, Steven. "LibGuides: African American Studies: Slavery at Princeton". libguides.princeton.edu. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Manegold (January 18, 2010), New England's scarlet 'S' for slavery; Manegold (2010), Ten Hills Farm: The Forgotten History of Slavery in the North, 41–42 Harper (2003), Slavery in Massachusetts; Bremer (2003), p. 314

- ^ Jon Butler, Becoming America: The Revolution Before 1776, p. 38, 2000

- ^ S 1539 Will of Wynflæd, circa AD 950 (11th-century copy, BL Cotton Charters viii. 38)

- ISBN 0714180572

- ^ Philip D. Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake", in Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory and Civic Culture, Eds. J.E. Lewis and P.S. Onuf. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, pp. 55–60.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Yancey, William Lowndes". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 902.

- ISBN 978-0889205666.

- ^ Wiseman, Maury. "David Levy Yulee: Conflict and Continuity in Social Memory". Jacksonville University. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Flint, Richard; Flint, Shirley Cushing. "Juan de Zaldívar". Office of the State Historia, Commission of Public Records, State Records Center and Archives. Retrieved 29 August 2015.