Slavonia

Slavonia

Slavonija | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | |

| Largest city | Osijek |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12,556 km2 (4,848 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)3 | |

| • Total | 665,858 |

| • Density | 53/km2 (140/sq mi) |

| ^ Slavonia is not designated as an official subdivision of Croatia; it is a historical region.[1] The flag and arms below are also unofficial/historical; none are legally defined at present.

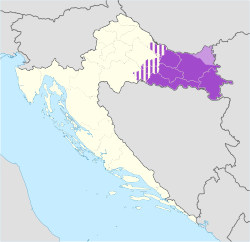

^ The map represents modern-day perception: historical boundaries of Slavonia varied over centuries. Vukovar-Srijem ). | |

History of Slavonia |

|---|

|

| History of Croatia |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Slavonia (

Slavonia is located in the Pannonian Basin, largely bordered by the Danube, Drava, and Sava rivers. In the west, the region consists of the Sava and Drava valleys and the mountains surrounding the Požega Valley, and plains in the east. Slavonia enjoys a moderate continental climate with relatively low precipitation.

After the

It became part of the Lands of the Hungarian Crown in the 12th century. The Ottoman conquest of Slavonia took place between 1536 and 1552. In 1699, after the Great Turkish War of 1683–1699, the Treaty of Karlowitz transferred Slavonia to the Habsburgs. After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Slavonia became part of the Hungarian part of the realm, and a year later it became part of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. In 1918, when Austria-Hungary dissolved, Slavonia became a part of the short-lived State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs which in turn became a part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, later renamed Yugoslavia. During the Croatian War of Independence of 1991–1995, Slavonia saw fierce fighting, including the 1991 Battle of Vukovar.

The economy of Slavonia is largely based on

The cultural heritage of Slavonia represents a blend of historical influences, especially those from the end of the 17th century, when Slavonia started recovering from the Ottoman wars, and its traditional culture. Slavonia contributed to the culture of Croatia through art, writers, poets, sculptors, and art patronage. In traditional music, Slavonia comprises a distinct region of Croatia, and the traditional culture is preserved through folklore festivals, with prominence given to tamburica music and bećarac, a form of traditional song, recognized as an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO. The cuisine of Slavonia reflects diverse influences—a blend of traditional and foreign elements. Slavonia is one of Croatia's winemaking areas, with Ilok and Kutjevo recognized as centres of wine production.

History

The name Slavonia originated in the

Prehistory and antiquity

Remnants of several

Middle Ages

After the collapse of the

The

Ottoman conquest

Following the Battle of Mohács, the Ottomans expanded their possessions in Slavonia seizing

The

Habsburg Monarchy and Austria-Hungary

The areas acquired through the

Kingdom of Yugoslavia and World War II

On 29 October 1918, the Croatian Sabor declared independence and decided to join the newly formed

In April 1941, Yugoslavia was occupied by Germany and Italy. Following the invasion the territory of Slavonia was incorporated into the Independent State of Croatia, a Nazi-backed puppet state and assigned as a zone under German occupation for the duration of World War II. The regime introduced anti-semitic laws and conducted a campaign of ethnic cleansing and genocide against Serb and Roma populations,[47] exemplified by the Jasenovac and Stara Gradiška concentration camps,[48] but to a much lesser extent in Slavonia than in other regions, due to strategic interests of the Axis in keeping peace in the area.[49] The largest massacre occurred in 1942 in Voćin.[50][page needed]

Armed resistance soon developed in the region, and by 1942, the Yugoslav Partisans controlled substantial territories, especially in mountainous parts of Slavonia.[51] The Serbian royalist Chetniks, who carried out genocide against Croat civilian population,[52] struggled to establish a significant presence in Slavonia throughout the war.[49] Partisans led by Josip Broz Tito took full control of Slavonia in April 1945.[53] After the war, the new Yugoslav government interned local Germans in camps in Slavonia, the largest of which were in Valpovo and Krndija, where many died of hunger and diseases.[54]

Federal Yugoslavia and the independence of Croatia

After World War II, Croatia—including Slavonia—became a

In the 1980s the political situation in Yugoslavia deteriorated with national tension fanned by the 1986 Serbian

In Slavonia, the first armed conflicts were clashes in

After the war, a number of towns and municipalities in the region were designated

Geography

Political geography

The

| County | Seat | Area (km2) | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brod-Posavina | Slavonski Brod | 2,043 | 130,782 |

| Osijek-Baranja | Osijek | 4,152 | 259,481 |

| Požega-Slavonia | Požega | 1,845 | 64,420 |

| Virovitica-Podravina | Virovitica | 2,068 | 70,660 |

Vukovar-Syrmia |

Vukovar | 2,448 | 144,438 |

| TOTAL: | 12,556 | 669,781 | |

| Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics[91][92] | |||

Physical geography

The boundaries of Slavonia, as a geographical region, do not necessarily coincide with the borders of the five counties, except in the south and east where the Sava and Danube rivers define them. The international borders of Croatia are boundaries common to both definitions of the region. In the north, the boundaries largely coincide because the Drava River is considered to be the northern border of Slavonia as a geographic region,[56] but this excludes Baranya from the geographic region's definition even though this territory is part of a county otherwise associated with Slavonia.[93][94][95] The western boundary of the geographic region is not specifically defined and it was variously defined through history depending on the political divisions of Croatia.[26] The eastern Croatia, as a geographic term, largely overlaps most definitions of Slavonia. It is defined as the territory of the Brod-Posavina, Osijek-Baranja, Požega-Slavonia, Virovitica-Podravina and Vukovar-Syrmia counties, including Baranya.[96]

Topography

| Mountain | Peak | Elevation | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psunj | Brezovo Polje | 984 m (3,228 ft) | 45°24′N 17°19′E / 45.400°N 17.317°E |

| Papuk | Papuk | 953 m (3,127 ft) | 45°32′N 17°39′E / 45.533°N 17.650°E |

| Krndija | Kapovac | 792 m (2,598 ft) | 45°27′N 17°55′E / 45.450°N 17.917°E |

Požeška Gora |

Kapavac | 618 m (2,028 ft) | 45°17′N 17°35′E / 45.283°N 17.583°E |

Slavonia is entirely located in the

The results of those processes are large

Hydrography and climate

The largest rivers in Slavonia are found along or near its borders—the Danube, Sava and Drava. The length of the Danube, flowing along the eastern border of Slavonia and through the cities of Vukovar and Ilok, is 188 kilometres (117 miles), and its main tributaries are the Drava 112-kilometre (70 mi) and the Vuka. The Drava discharges into the Danube near

The entire Slavonia belongs to the

Most of Croatia, including Slavonia, has a moderately warm and rainy humid continental climate as defined by the Köppen climate classification. Mean annual temperature averages 10 to 12 °C (50 to 54 °F), with the warmest month, July, averaging just below 22 °C (72 °F). Temperature peaks are more pronounced in the continental areas—the lowest temperature of −27.8 °C (−18.0 °F) was recorded on 24 January 1963 in Slavonski Brod,[107] and the highest temperature of 40.5 °C (104.9 °F) was recorded on 5 July 1950 in Đakovo.[108] The least precipitation is recorded in the eastern parts of Slavonia at less than 700 millimetres (28 inches) per year, however in the latter case, it mostly occurs during the growing season. The western parts of Slavonia receive 900 to 1,000 millimetres (35 to 39 inches) precipitation. Low winter temperatures and the distribution of precipitation throughout the year normally result in snow cover, and freezing rivers—requiring use of icebreakers, and in extreme cases explosives,[109] to maintain the flow of water and navigation.[110] Slavonia receives more than 2,000 hours of sunshine per year on average. Prevailing winds are light to moderate, northeasterly and southwesterly.[91]

Demographics

According to the 2011 census, the total population of the five counties of Slavonia was 806,192, accounting for 19% of population of Croatia. The largest portion of the total population of Slavonia lives in Osijek-Baranja county, followed by Vukovar-Syrmia county. Požega-Slavonia county is the least populous county of Slavonia. Overall the population density stands at 64.2 persons per square kilometre. The population density ranges from 77.6 to 40.9 persons per square kilometre, with the highest density recorded in Brod-Posavina county and the lowest in Virovitica-Podravina county. Osijek is the largest city in Slavonia, followed by Slavonski Brod, Vinkovci and Vukovar. Other cities in Slavonia have populations below 20,000.

The demographic history of Slavonia is characterised by significant migrations, as is that of Croatia as a whole, starting with the arrival of the Croats, between the 6th and 9th centuries.

| Rank | City | County | Urban population | Municipal population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Osijek | Osijek-Baranja | 83,496 | 107,784 |

| 2 | Slavonski Brod | Brod-Posavina | 53,473 | 59,507 |

| 3 | Vinkovci | Vukovar-Syrmia |

31,961 | 35,375 |

| 4 | Vukovar | Vukovar-Syrmia | 26,716 | 28,016 |

| 5 | Požega | Požega-Slavonia | 19,565 | 26,403 |

| 6 | Đakovo | Osijek-Baranja | 19,508 | 27,798 |

| 7 | Virovitica | Virovitica-Podravina | 14,663 | 21,327 |

| 8 | Županja | Vukovar-Syrmia | 12,115 | 12,185 |

| 9 | Nova Gradiška | Brod-Posavina | 11,767 | 14,196 |

| 10 | Slatina | Virovitica-Podravina | 10,152 | 13,609 |

| County seats are indicated with bold font. Sources: Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 2011 Census[92] | ||||

Since the end of the 19th century there was substantial economic emigration abroad from Croatia in general.[116][117] After World War I, the Yugoslav regime confiscated up to 50 percent of properties and encouraged settlement of the land by Serb volunteers and war veterans in Slavonia,[26] only to have them evicted and replaced by up to 70,000 new settlers by the regime during World War II.[118] During World War II and in the period immediately following the war, there were further significant demographic changes, as the German-speaking population, the Danube Swabians, were either forced or otherwise compelled to leave—reducing their number from the prewar German population of Yugoslavia of 500,000, living in Slavonia and other parts of present-day Croatia and Serbia, to the figure of 62,000 recorded in the 1953 census.[119] The 1940s and the 1950s in Yugoslavia were marked by colonisation of settlements where the displaced Germans used to live, by people from the mountainous parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro, and migrations to larger cities spurred on by the development of industry.[120] [failed verification] In the 1960s and 1970s, another wave of economic migrants left—largely moving to Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Western Europe.[121][122][123]

The most recent changes to the ethnic composition of Slavonian counties occurred between censuses conducted in 1991 and 2001. The 1991 census recorded a heterogenous population consisting mostly of Croats and Serbs—at 72 percent and 17 percent of the total population respectively. The Croatian War of Independence, and the ethnic fracturing of Yugoslavia that preceded it, caused an exodus of the Croat population followed by an exodus of Serbs. The return of refugees since the end of hostilities is not complete—a majority of Croat refugees returned, while fewer Serbs did. In addition, ethnic Croats moved to Slavonia from Bosnia and Herzegovina and from Serbia.[83]

Economy and transport

The economy of Slavonia is largely based on

The gross domestic product (GDP) of the five counties in Slavonia combined (in year 2008) amounted to 6,454 million euro, or 8,005 euro per capita—27.5% below Croatia's national average. The GDP of the five counties represented 13.6% of Croatia's GDP.[130] Several Pan-European transport corridors run through Slavonia: corridor Vc as the A5 motorway, corridor X as the A3 motorway and a double-track railway spanning Slavonia from west to east, and corridor VII—the Danube River waterway.[131] The waterway is accessed through the Port of Vukovar, the largest Croatian river port, situated on the Danube itself, and the Port of Osijek on the Drava River, 14.5 kilometres (9.0 miles) away from confluence of the rivers.[132]

Another major sector of the economy of Slavonia is agriculture, which also provides part of the raw materials for the processing industry. Out of 1,077,403 hectares (2,662,320 acres) of utilized agricultural land in Croatia, 493,878 hectares (1,220,400 acres), or more than 45%, are found in Slavonia, with the largest portion of the land situated in the Osijek-Baranja and Vukovar-Syrmia counties. The largest areas are used for production of

| Counties of Slavonia by GDP, in million Euro

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

| Brod-Posavina | 575 | 643 | 699 | 717 | 782 | 786 | 869 | 931 | 1,074 | 968 |

| Osijek-Baranja | 1,370 | 1,499 | 1,699 | 1,710 | 1,884 | 1,999 | 2,193 | 2,538 | 2,844 | 2,590 |

| Požega-Slavonia | 337 | 371 | 395 | 428 | 456 | 472 | 484 | 541 | 557 | 510 |

| Virovitica-Podravina | 378 | 434 | 465 | 478 | 493 | 497 | 584 | 616 | 661 | 561 |

| Vukovar-Srijem | 651 | 723 | 795 | 836 | 889 | 964 | 1,098 | 1,144 | 1,318 | 1,180 |

| Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics[134][135][136][137] | ||||||||||

| Counties of Slavonia by GDP per capita, in Euro

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

| Brod-Posavina | 3,260 | 3,633 | 3,955 | 4,065 | 4,452 | 4,487 | 4,972 | 5,345 | 6,183 | 5,606 |

| Osijek-Baranja | 4,147 | 4,537 | 5,149 | 5,199 | 5,750 | 6,127 | 6,757 | 7,875 | 8,871 | 8,112 |

| Požega-Slavonia | 3,934 | 4,320 | 4,610 | 5,020 | 5,383 | 5,605 | 5,786 | 6,505 | 6,750 | 6,229 |

| Virovitica-Podravina | 4,045 | 4,654 | 5,016 | 5,176 | 5,410 | 5,485 | 6,497 | 6,923 | 7,485 | 6,399 |

| Vukovar-Srijem | 3,184 | 3,528 | 3,903 | 4,127 | 4,414 | 4,807 | 5,501 | 5,756 | 6,647 | 5,974 |

| Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics[134][135][136][137] | ||||||||||

In 2010, only two companies headquartered in Slavonia ranked among top 100

Culture

The

The heritage of the region includes numerous

Slavonia significantly contributed to the culture of Croatia as a whole, both through works of artists and through patrons of the arts—most notable among them being Josip Juraj Strossmayer.[167] Strossmayer was instrumental in the establishment of the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts, later renamed the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts,[168] and the reestablishment of the University of Zagreb.[169] A number of Slavonia's artists, especially writers, made considerable contributions to Croatian culture. Nineteenth-century writers who are most significant in Croatian literature include Josip Eugen Tomić, Josip Kozarac, and Miroslav Kraljević—author of the first Croatian novel.[167] Significant twentieth-century poets and writers in Slavonia were Dobriša Cesarić, Dragutin Tadijanović, Ivana Brlić-Mažuranić and Antun Gustav Matoš.[170] Painters associated with Slavonia, who contributed greatly to Croatian art, were Miroslav Kraljević and Bela Čikoš Sesija.[171]

Slavonia is a distinct region of Croatia in terms of ethnological factors in traditional music. It is a region where traditional culture is preserved through folklore festivals. Typical traditional music instruments belong to the tamburica and bagpipe family.[172] The tamburica is the most representative musical instrument associated with Slavonia's traditional culture. It developed from music instruments brought by the Ottomans during their rule of Slavonia, becoming an integral part of the traditional music, its use surpassing or even replacing the use of bagpipes and gusle.[173] A distinct form of traditional song, originating in Slavonia, the bećarac, is recognized as an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO.[174][175]

Out of 122 Croatia's universities and other institutions of

Cuisine and wines

The cuisine of Slavonia reflects cultural influences on the region through the diversity of its culinary influences. The most significant among those were from Hungarian, Viennese, Central European, as well as Turkish and Arab cuisines brought by series of conquests and accompanying social influences. The ingredients of traditional dishes are pickled vegetables, dairy products and smoked meats.[185] The most famous traditional preserved meat product is kulen, one of a handful Croatian products protected by the EU as indigenous products.[186]

Slavonia is one of Croatia's winemaking sub-regions, a part of its continental winegrowing region. The best known winegrowing areas of Slavonia are centered on

Slavonian

See also

References

- ^ ISBN 1-57607-800-0. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ISSN 1333-2546. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ISSN 0473-0992. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ISSN 1330-0644. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ISSN 0473-0992. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ISSN 0473-0992. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Ministry of Culture (Croatia). Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- Ministry of Culture (Croatia). Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ISSN 1330-0644. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-631-19807-9. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-7100-7714-1. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ISBN 978-90-04-18646-0. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ISBN 978-5-4469-0970-4. Archived from the original(PDF) on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ ISSN 1332-4853. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ "Slavonija". Croatian Encyclopedia. Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography. 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Sabor. Archivedfrom the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Frucht 2005, p. 422-423

- ISSN 0351-9767. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Zakon o grbu, zastavi i himni Republike Hrvatske te zastavi i lenti predsjednika Republike Hrvatske" [Coat of Arms, Flag and Anthem of the Republic of Croatia, Flag and Sash of the President of the Republic of Croatia Act]. Narodne Novine (in Croatian). 21 December 1990. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ Davor Brunčić (2003). "The symbols of Osijek-Baranja County" (PDF). Osijek-Baranja County. p. 44. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- Miroslav Krleža Lexicographical Institute. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ISSN 0351-9767. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ Lane (1973), p. 409

- ^ ISSN 1846-8314. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Povijest Gradišćanskih Hrvatov" [History of Burgenland Croats] (in Croatian). Croatian Cultural Association in Burgenland. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Nihad Kulenović, 2016, Cross border cooperation between Baranja and Tuzla Region, http://baza.gskos.hr/Graniceidentiteti.pdf #page=234

- ^

Kaser, Karl (1997). Slobodan seljak i vojnik: Rana krajiška društva, 1545-1754. Naprijed. ISBN 978-953-178-064-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-253-30368-4. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-5017-0194-8.

- ^ Nenad Moačanin, 2003, Požega i Požeština u sklopu Osmanlijskoga carstva : (1537.-1691.),{1555. svi obveznici "klasičnih" rajinskih dažbina u Srijemu i Slavoniji nazvani su "vlasima", što uključuje ne samo starosjedilačko hrvatsko pučanstvo nego i Mađare!), Neki su se dakle starosjedioci vraćali, a dijelom su kolonisti sa statusom koji je imao nekih sličnosti s vlaškim (a da sami nisu nužno bili ni porijeklom Vlasi) dolazili iz prekosavskih krajeva, posebice s područja Soli i Usore, nastavljajući tako proces započet već nakon 1521. Ako bi se ta pojava mogla povezati s preseljenjem, uglavnom u Podunavlje, 10 000 obitelji iz Kliskog sandžaka nakon pobune (1604?)98, i ako je prihvatljivo da ih se dosta naselilo i oko Požege, onda bismo možda mogli djelomice tumačiti bune i hajdučiju u to vrijeme dolaskom "buntovnijeg" pučanstva. Novo je stanovništvo moglo doći i s područja Bosanskog sandžaka, ali za sada se "kliska" pretpostavka čini nešto sigurnijom} http://baza.gskos.hr/cgi-bin/unilib.cgi?form=D1430506006 #page=35,40,80

- ISSN 1332-2567. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ ISSN 1845-4380. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Constitution of Union between Croatia-Slavonia and Hungary". H-net.org. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ISSN 1330-349X. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ISSN 0032-3241. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Slavonia Round Trip". Get-by-bus. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

- ^ Craig, G.A. (1966). Europe since 1914. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York.

- The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

Virtually the entire population of what remained of Hungary regarded the Treaty of Trianon as manifestly unfair, and agitation for revision began immediately.

- ISSN 1332-4853. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ISSN 1330-0474. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-7425-1784-4. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ Klemenčić, Žagar 2004, p. 121–123

- ^ Klemenčić, Žagar 2004, p. 153–156

- ISSN 0570-9008. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-86-343-0010-9.

- ISBN 978-953-7442-13-2. Archived from the original(PDF) on 13 March 2018.

- ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Klemenčić, Žagar 2004, p. 184

- ISSN 0582-673X.

- ^ Geiger, Vladimir (2006). "Logori za folksdojčere u Hrvatskoj nakon Drugoga svjetskog rata 1945-1947" [Camps for Volksdeutsch in Croatia after the Second World War, 1945 to 1947]. Časopis Za Suvremenu Povijest (in Croatian). 38 (3): 1098, 1100.

- . Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ ISSN 0570-9008. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ Frucht 2005, p. 433

- ^ "Leaders of a Republic in Yugoslavia Resign". The New York Times. Reuters. 12 January 1989. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ISSN 1847-2397. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Branka Magas (13 December 1999). "Obituary: Franjo Tudjman". The Independent. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Chuck Sudetic (2 October 1990). "Croatia's Serbs Declare Their Autonomy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Chuck Sudetic (26 June 1991). "2 Yugoslav States Vote Independence To Press Demands". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "Ceremonial session of the Croatian Parliament on the occasion of the Day of Independence of the Republic of Croatia". Official web site of the Parliament of Croatia. Sabor. 7 October 2004. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ a b Chuck Sudetic (4 November 1991). "Army Rushes to Take a Croatian Town". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "Croatia Clashes Rise; Mediators Pessimistic". The New York Times. 19 December 1991. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Charles T. Powers (1 August 1991). "Serbian Forces Press Fight for Major Chunk of Croatia". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Stephen Engelberg (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Stephen Engelberg (4 March 1991). "Serb-Croat Showdown in One Village Square". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Stephen Engelberg (5 May 1991). "One More Dead as Clashes Continue in Yugoslavia". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Nation 2004, p. 5.

- ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ^ Roger Cohen (2 May 1995). "CROATIA HITS AREA REBEL SERBS HOLD, CROSSING U.N. LINES". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Chuck Sudetic (18 November 1991). "Croats Concede Danube Town's Loss". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Eugene Brcic (29 June 1998). "Croats bury victims of Vukovar massacre". The Independent. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Chuck Sudetic (3 January 1992). "Yugoslav Factions Agree to U.N. Plan to Halt Civil War". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Carol J. Williams (29 January 1992). "Roadblock Stalls U.N.'s Yugoslavia Deployment". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- PMID 7726618.

- ^ Zdravko Tomac (15 January 2010). "Strah od istine" [Fear of the Truth]. Portal of Croatian Cultural Council (in Croatian). Hrvatsko kulturno vijeće. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Dean E. Murphy (8 August 1995). "Croats Declare Victory, End Blitz". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Chris Hedges (16 January 1998). "An Ethnic Morass Is Returned to Croatia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Zakon o područjima županija, gradova i općina u Republici Hrvatskoj" [Territories of Counties, Cities and Municipalities of the Republic of Croatia Act]. Narodne novine (in Croatian). 28 July 2006. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ^ ISSN 1333-2546. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Ankica Barbir-Mladinović (29 September 2010). "U dijelu Hrvatske BDP na razini devedesetih" [In a part of Croatia, GDP hits 1990s level]. Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Croatian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ "Opći podaci o Brodsko-posavskoj županiji" [General information on Brod-Posavina County] (in Croatian). Brod-Posavina County. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Local self-government". Osijek-Baranja County. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Opći podaci o županiji" [General information on the county] (in Croatian). Požega-Slavonia County. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Virovitičko-podravska županija kroz povijest" [Virovitica-Podravina County through history] (in Croatian). Virovitica-Podravina County. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- Vukovar-Syrmia County. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ "Nacionalno izviješće Hrvatska" [Croatia National Report] (PDF) (in Croatian). Council of Europe. January 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f "2010 – Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Croatia" (PDF). Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "Census 2011 First Results". Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 29 June 2011. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ Ministry of Culture (Croatia). Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ Silvana Fable (12 May 2011). "Jakovčić predložio Hrvatsku u četiri regije – Slavonija i Baranja, Istra, Dalmacija i Zagreb" [Jakovčić proposes Croatia of four regions – Slavonija and Baranja, Istria, Dalmatia and Zagreb]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ "Slavonija i Baranja – Riznica tradicije, ljepota prirode i burne povijesti" [Slavonia and Baranya – Treasuring tradition, natural heritage and tumultuous history]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 7 August 2010. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ISSN 1330-349X.

- Ministry of Construction and Spatial Planning (Croatia). November 2006. Archived from the original(PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ISBN 978-94-007-2447-1. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ISBN 978-90-5011-276-5. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- S2CID 34321638. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- Papuk Geopark. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ISSN 1868-4556. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ISSN 1846-0925. Archived from the original(PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- Ministry of Environment and Nature Protection (Croatia). February 2006. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ]

- ^ "Pravilnik o područjima podslivova, malih slivova i sektora" [Ordinance on areas of sub-catchments, minor catchments and sectors]. Narodne Novine (in Croatian). 11 August 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ "Apsolutno najniža temperatura zraka u Hrvatskoj" [The absolute lowest air temperature in Croatia] (in Croatian). Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service. 3 February 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- INA: 88–92. Retrieved 13 March 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ivana Barišić (14 February 2012). "Vojska sa 64 kilograma eksploziva razbila led na Dravi kod Osijeka" [Army breaks Drava River ice near Osijek using 64 kilograms of explosives]. Večernji list (in Croatian). Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ "Ledolomci na Dunavu i Dravi" [Icebreakers on Danube and Drava] (in Croatian). Croatian Radiotelevision. 13 February 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Popis stanovništva 2001" [2001 Census]. Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Mužić (2007), pp. 249–293

- ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ISSN 1333-2546. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Jelena Lončar (22 August 2007). "Iseljavanje Hrvata u Amerike te Južnu Afriku" [Migrations of Croats to the Americas and the South Africa] (in Croatian). Croatian Geographic Society. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ISSN 1330-0474.

- ISBN 978-1-55753-443-9. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Migrations in the territory of former Yugoslavia from 1945 until present time" (PDF). University of Ljubljana. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration (Croatia). Archived from the originalon 13 August 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Hrvatsko iseljeništvo u Australiji" [Croatian diaspora in Australia] (in Croatian). Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration (Croatia). Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Stanje hrvatskih iseljenika i njihovih potomaka u inozemstvu" [Balance of Croatian Emigrants and their Descendants Abroad] (in Croatian). Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration (Croatia). Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Županijska razvojna strategija Brodsko-posavske županije" [County development strategy of the Brod-Posavina County] (PDF) (in Croatian). Slavonski Brod: Brod-Posavina County. March 2011. pp. 27–40. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Informacija o stanju gospodarstva Vukovarsko-srijemske županije" [Information on state of economy of the Vukovar-Srijem County] (PDF) (in Croatian). Vukovar-Srijem County. September 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "County economy". Osijek-Baranja County. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Gospodarstvo Virovitičko-podravske županije" [Economy of Virovitica-Podravina County] (in Croatian). Croatian Employment Service. Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Gospodarstvo Brodsko-posavske županije" [Economy of Brod-Posavina County] (in Croatian). Brod-Posavina County. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Gospodarski profil županije" [Economic profile of the county] (in Croatian). Požega-Slavonia County. Archived from the original on 3 December 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT FOR REPUBLIC OF CROATIA, STATISTICAL REGIONS AT LEVEL 2 AND COUNTIES, 2008". Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 11 February 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Transport: launch of the Italy-Turkey pan-European Corridor through Albania, Bulgaria, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Greece". European Union. 9 September 2002. Retrieved 6 September 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Priručnik za unutarnju plovidbu u Republici Hrvatskoj" [Manual of inland waterways navigation in the Republic of Croatia] (PDF) (in Croatian). Centar za razvoj unutarnje plovidbe d.o.o. December 2006. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Popis poljoprivrede 2003" [2003 Agricultural Census] (in Croatian). Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ ISSN 1334-0565.

- ^ ISSN 1330-0350.

- ^ ISSN 1330-0350.

- ^ ISSN 1330-0350.

- ^ "About us". Belje d.d. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Od 1884. do danas" [From 1884 until today] (in Croatian). Belišće d.d. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Na čvrstim temeljima povijesti" [On solid foundations of history] (in Croatian). Osijek-Koteks. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Company profile". Saponia. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "About us". Biljemerkant. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Structure of shareholders". Nexe Grupa. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "History of the factory". Viro. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "About us". Đuro Đaković Holding. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Vision and mission". Kutjevo d.d. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Vupik" (in Croatian). Agrokor. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- Croatian Chamber of Commerce: 38–50. July 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Prandau – Mailath Castle". Osijek-Baranja County Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Dvorac Prandau – Normann" [Prandau – Normann Castle] (in Croatian). Osijek-Baranja County Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "The castle in Bilje". Osijek-Baranja County Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "The castle in Darda". Osijek-Baranja County Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "The castle in Tikveš". Osijek-Baranja County Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "The castle in Kneževo". Osijek-Baranja County Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Najljepši hrvatski dvorci" [The most beautiful castles of Croatia] (in Croatian). t-portal.hr. 18 November 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "The Odescalchi Castle -The Ilok town Museum". City of Ilok Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "The Eltz Castle". City of Vukovar Tourist Board. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Otvoren obnovljeni dvorac Eltz" [Reconstructed Eltz manor house opens] (in Croatian). Croatian Radiotelevision. 30 October 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Isusovački dvorac Kutjevo" [Kutjevo Jesuit manor house] (in Croatian). Požega-Slavonia County Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "Barokni dvorac Cernik" [Baroque Cernik manor house] (in Croatian). Brod-Posavina County Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "Tvrđa". Essential Osijek. In Your Pocket. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ISSN 1332-4853. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- Papuk Nature Park. Archived from the originalon 25 April 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "Đakovo". Croatian National Tourist Board. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "Kulturno-povijesna baština Osječko-baranjske županije" [Cultural and historical heritage of Osijek-Baranja County] (PDF) (in Croatian). Osijek-Baranja County Tourist Board. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "O turizmu" [About tourism] (in Croatian). Erdut Municipality Tourist Board. 3 May 2011. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Ministry of Culture (Croatia). Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ "The Founding of the Academy". Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Archived from the original on 6 June 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ "University of Zagreb 1699 – 2005". University of Zagreb. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Ministry of Culture (Croatia). Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Ministry of Culture (Croatia). Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Ministry of Culture (Croatia). Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Ministry of Culture (Croatia). Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ "UNESCO uvrstio bećarac u svjetsku baštinu!" [UNESCO lists bećarac as world heritage!] (in Croatian). 28 November 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ "Bećarac singing and playing from Eastern Croatia". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ "Higher education institutions in the Republic of Croatia". Agency for Science and Higher Education (Croatia). Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "Universities in Croatia". Agency for Science and Higher Education (Croatia). Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "Polytechnics in Croatia". Agency for Science and Higher Education (Croatia). Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "Colleges in Croatia". Agency for Science and Higher Education (Croatia). Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "History of Higher Education in Osijek". University of Osijek. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "Povijest" [History] (in Croatian). University of Osijek. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "Požeška Gimnazija" [Požega gymasium] (in Croatian). City of Požega Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "A brief survey of Gymnasium". Požega Gymnasium. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ISSN 0351-3947. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "Slavonija" [Slavonia] (in Croatian). Podravka. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Marinko Petković (21 August 2011). "Paška sol prvi autohtoni proizvod s Unijinom oznakom izvornosti" [Pag slat as the first indigenous product to receive the EU authenticity certificate] (in Croatian). Vjesnik. Retrieved 1 April 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Ilok" [Ilok]. Croatian National Tourist Board. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Davor Butković (20 June 2009). "Hrvatskoj čak osam zlatnih medalja za vina!" [Croatian wines awarded as many as eight gold medals!]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ "TOP 10 vinara: Kraljica graševina... A onda sve ostalo!" [Top 10 winemakers: Graševina reigns... and everything else follows!]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 7 August 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Savino, Anna (September 2015). "The Effects of Oak on Nebbiolo". Langhe.Net. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

Bibliography

- Richard C. Frucht (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Matjaž Klemenčič; Mitja Žagar (2004). The former Yugoslavia's diverse peoples: a reference sourcebook. ISBN 978-1-57607-294-3. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- Frederic Chapin Lane (1973). Venice, a Maritime Republic. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-1460-0. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Ivan Mužić (2007). Hrvatska povijest devetoga stoljeća [Croatian Ninth Century History] (PDF) (in Croatian). Naklada Bošković. ISBN 978-953-263-034-3. Archived from the original(PDF) on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- Nation, R. Craig (2004). War in the Balkans, 1991–2002. ISBN 978-1-4102-1773-8. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Taube, Friedrich Wilhelm von (1777). Historische und geographische Beschreibung des Königreiches Slavonien und des Herzogthumes Syrmien. Vol. 1. Leipzig.

- Taube, Friedrich Wilhelm von (1777). Historische und geographische Beschreibung des Königreiches Slavonien und des Herzogthumes Syrmien. Vol. 2. Leipzig.

- Taube, Friedrich Wilhelm von (1778). Historische und geographische Beschreibung des Königreiches Slavonien und des Herzogthumes Syrmien. Vol. 3. Leipzig.