Slavonic-Serbian

| Slavonic-Serbian | |

|---|---|

| Славено-сербскiй | |

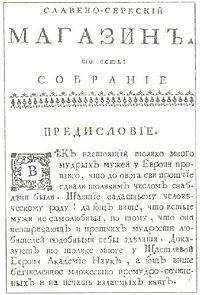

Cover of the 1768 edition of the Slavenoserbskij Magazin | |

| Region | Vojvodina |

| Era | 18th to 19th century |

Indo-European

| |

Early form | |

Old Cyrillic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| South Slavic languages and dialects |

|---|

Slavonic-Serbian (славяносербскій, slavjanoserbskij), Slavo-Serbian, or Slaveno-Serbian (славено-сербскiй, slaveno-serbskij;

History

At the beginning of the 18th century, the literary language of the Serbs was the Serbian recension of

Around that time, laymen became more numerous and notable than monks and priests among active Serbian writers. The secular writers wanted their works to be closer to the general Serbian readership, but at the same time, most of them regarded Church Slavonic as more prestigious and elevated than the popular Serbian language. Church Slavonic was also identified with the Proto-Slavic language, and its use in literature was seen as the continuation of an ancient tradition. The writers began blending Russo-Slavonic, vernacular Serbian, and Russian, and the resulting mixed language is called Slavonic-Serbian. The first printed work in Slavonic-Serbian appeared in 1768, written by Zaharije Orfelin. Before that, a German–Slavonic-Serbian dictionary was composed in the 1730s. The blended language became dominant in secular Serbian literature and publications during the 1780s and 1790s.[6] At the beginning of the 19th century, it was severely attacked by Vuk Karadžić and his followers, whose reformatory efforts formed modern literary Serbian based on the popular language.[7] The last notable work in Slavonic-Serbian was published in 1825.[8]

Slavonic-Serbian was used in literary works, including prose and poetry, school textbooks, philological and theological works,

Characteristics

Slavonic-Serbian texts exhibit

| Slavonic-Serbian | Transliteration | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Честь имамъ всѣмъ Высокопочитаемымъ Читателемъ обявити, да безъ сваке сумнѣ намѣренъ есамъ, ону достохвалну и цѣлому Сербскому Роду преполезну ИСТОРИЮ СЕРБСКУ, от коесамъ цѣло оглавленïе давно сообщïо, печатати. | Čest' imam vsěm Vysokopočitaemym Čitatelem objaviti, da bez svake sumně naměren esam, onu dostohvalnu i cělomu Serbskomu Rodu prepoleznu ISTORIJU SERBSKU, ot koesam cělo oglavlenie davno soobštio, pečatati. | I have the honour to announce to all Revered Readers that I am, without any doubt, intent on printing that praiseworthy and to all Serbian People valuable SERBIAN HISTORY, a whole chapter of which I have published long ago. |

| Modern Serbian | Transliteration | |

| Част имам објавити свим Високопоштованим Читаоцима да сам без сваке сумње намерен штампати ону доста хваљену и целоме Српском Роду прекорисну ИСТОРИЈУ СРПСКУ, од које сам цело поглавље давно саопштио. | Čast imam objaviti svim Visokopoštovanim Čitaocima da sam bez svake sumnje nameren štampati onu dosta hvaljenu i celome Srpskom Rodu prekorisnu ISTORIJU SRPSKU, od koje sam celo poglavlje davno saopštio. |

See also

Notes

- ^ Mladenović, Aleksandar (1973). "Tipovi knjizevnog jezika Srba u 18. veku". Novi Sad.

- ^ Albin 1970, p. 484

- ^ Ivić 1998, pp. 105–6

- ^ Ivić 1998, pp. 116–19

- ^ Paxton 1981, pp. 107–9

- ^ a b Ivić 1998, pp. 129–33

- ^ a b Albin 1970, pp. 489–91

- ^ Ivić 1998, p. 194

- Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža, 1999–2009

- ^ Gudkov 1993, pp. 79–81

- ^ Ivić 1998, pp. 134–35

- ^ Ivanova 2010, p. 259

References

- Albin, Alexander (1970). "The Creation of the Slaveno-Serbski Literary Language". JSTOR 4206278.

- Gudkov, Vladimir Pavlovich (1993). Сербская лексикография XVIII века [Serbian Lexicography of the 18th Century] (in Russian). Moscow: Philological Faculty of the Moscow State University.

- Ivanova, Najda (2010). Славеносрпски језик између 'простоте' и 'совершенства' [Slaveno-Serbian Language between 'Simplicity' and 'Perfection']. Južnoslovenski Filolog (in Serbian). 66 (66). Belgrade: Institute for the Serbian Language of the ISSN 0350-185X.

- OCLC 500282371.

- Paxton, Roger V. (1981). "Identity and Consciousness: Culture and Politics among the Habsburg Serbs in the Eighteenth Century". In ISBN 978-0914710899.