Slum

| |||||||||||||

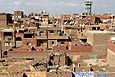

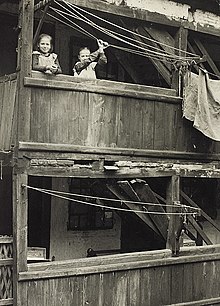

A slum is a highly populated

Due to increasing urbanization of the general populace, slums became common in the 19th to late 20th centuries in the United States and Europe.

Slums form and grow in different parts of the world for many different reasons. Causes include rapid rural-to-urban migration, economic stagnation and depression, high unemployment, poverty, informal economy, forced or manipulated ghettoization, poor planning, politics, natural disasters, and social conflicts.[1][11][12] Strategies tried to reduce and transform slums in different countries, with varying degrees of success, include a combination of slum removal, slum relocation, slum upgrading, urban planning with citywide infrastructure development, and public housing.[13][14]

The UN defines slums as[15]

.... individuals living under the same roof lacking one or more of the following conditions: access to improved water, access to improved sanitation, sufficient living area, housing durability, and security of tenure

Etymology and nomenclature

It is thought

Numerous other non-English terms are often used interchangeably with slum: shanty town, favela, rookery, gecekondu, skid row, barrio, ghetto, banlieue, bidonville, taudis, bandas de miseria, barrio marginal, morro, paragkoupoli, loteamento, barraca, musseque, iskuwater, Inner city, tugurio, solares, mudun safi, kawasan kumuh, karyan, medina achouaia, brarek, ishash, galoos, tanake, baladi, trushchoby, chalis, katras, zopadpattis, ftohogeitonia, basti, estero, looban, dagatan, umjondolo, watta, udukku, and chereka bete.[17]

The word slum has negative connotations, and using this label for an area can be seen as an attempt to delegitimize that land use when hoping to repurpose it.[18]

History

Before the 19th century, rich and poor people lived in the same districts, with the wealthy living on the high streets, and the poor in the service streets behind them. But in the 19th century, wealthy and upper-middle-class people began to move out of the central part of rapidly growing cities, leaving poorer residents behind.[19]

Slums were common in the United States and Europe before the early 20th century. London's East End is generally considered the locale where the term originated in the 19th century, where massive and rapid urbanization of the dockside and industrial areas led to intensive overcrowding in a warren of post-medieval streetscape. The suffering of the poor was described in popular fiction by moralist authors such as

Slums are often associated with

Close under the Abbey of Westminster there lie concealed labyrinths of lanes and potty and alleys and slums, nests of ignorance, vice, depravity, and crime, as well as of squalor, wretchedness, and disease; whose atmosphere is typhus, whose ventilation is cholera; in which swarms of huge and almost countless population, nominally at least, Catholic; haunts of filth, which no sewage committee can reach – dark corners, which no lighting board can brighten.[25]

This passage was widely quoted in the national press,[26] leading to the popularization of the word slum to describe bad housing.[24][27]

In France as in most industrialised European capitals, slums were widespread in Paris and other urban areas in the 19th century, many of which continued through first half of the 20th century. The first

New York City is believed to have created the United States' first slum, named the Five Points in 1825, as it evolved into a large urban settlement.[5][37] Five Points was named for a lake named Collect.[37][38] which, by the late 1700s, was surrounded by slaughterhouses and tanneries which emptied their waste directly into its waters. Trash piled up as well and by the early 1800s the lake was filled up and dry. On this foundation was built Five Points, the United States' first slum. Five Points was occupied by successive waves of freed slaves, Irish, then Italian, then Chinese, immigrants. It housed the poor, rural people leaving farms for opportunity, and the persecuted people from Europe pouring into New York City. Bars, bordellos, squalid and lightless tenements lined its streets. Violence and crime were commonplace. Politicians and social elite discussed it with derision. Slums like Five Points triggered discussions of affordable housing and slum removal. As of the start of the 21st century, Five Points slum had been transformed into the Little Italy and Chinatown neighborhoods of New York City, through that city's campaign of massive urban renewal.[4][37]

Five Points was not the only slum in America.

A type of slum housing, sometimes called poorhouses, crowded Boston Common, later at the fringes of the city.[41]

Rio de Janeiro documented its first slum in 1920 census. By the 1960s, over 33% of population of Rio lived in slums, 45% of Mexico City and Ankara, 65% of Algiers, 35% of Caracas, 25% of Lima and Santiago, 15% of Singapore. By 1980, in various cities and towns of Latin America alone, there were about 25,000 slums.[46]

Causes that create and expand slums

Slums sprout and continue for a combination of demographic, social, economic, and political reasons. Common causes include rapid rural-to-urban migration, poor planning, economic stagnation and depression, poverty, high unemployment, informal economy, colonialism and segregation, politics, natural disasters and social conflicts.

Rural–urban migration

Rural–urban migration is one of the causes attributed to the formation and expansion of slums.[1] Since 1950, world population has increased at a far greater rate than the total amount of arable land, even as agriculture contributes a much smaller percentage of the total economy. For example, in India, agriculture accounted for 52% of its GDP in 1954 and only 19% in 2004;[50] in Brazil, the 2050 GDP contribution of agriculture is one-fifth of its contribution in 1951.[51] Agriculture, meanwhile, has also become higher yielding, less disease prone, less physically harsh and more efficient with tractors and other equipment. The proportion of people working in agriculture has declined by 30% over the last 50 years, while global population has increased by 250%.[1]

Many people move to

According to Ali and Toran,

Urbanization

The formation of slums is closely linked to

Some scholars suggest that urbanization creates slums because local governments are unable to manage urbanization, and

Another type of urbanization does not involve economic growth but economic stagnation or low growth, mainly contributing to slum growth in Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia. This type of urbanization involves a high rate of unemployment, insufficient financial resources and inconsistent urban planning policy.[66] In these areas, an increase of 1% in urban population will result in an increase of 1.84% in slum prevalence.[67]

Urbanization might also force some people to live in slums when it influences

Many slums are part of economies of agglomeration in which there is an emergence of economies of scale at the firm level, transport costs and the mobility of the industrial labour force.[69] The increase in returns of scale will mean that the production of each good will take place in a single location.[69] And even though an agglomerated economy benefits these cities by bringing in specialization and multiple competing suppliers, the conditions of slums continue to lag behind in terms of quality and adequate housing. Alonso-Villar argues that the existence of transport costs implies that the best locations for a firm will be those with easy access to markets, and the best locations for workers, those with easy access to goods. The concentration is the result of a self-reinforcing process of agglomeration.[69] Concentration is a common trend of the distribution of population. Urban growth is dramatically intense in the less developed countries, where a large number of huge cities have started to appear; which means high poverty rates, crime, pollution and congestion.[69]

Poor house planning

Lack of affordable low-cost housing and poor planning encourages the supply side of slums.[70] The Millennium Development Goals proposes that member nations should make a "significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers" by 2020.[71] If member nations succeed in achieving this goal, 90% of the world total slum dwellers may remain in the poorly housed settlements by 2020.[72] Choguill claims that the large number of slum dwellers indicates a deficiency of practical housing policy.[72] Whenever there is a significant gap in growing demand for housing and insufficient supply of affordable housing, this gap is typically met in part by slums.[70] The Economist has observed that "good housing is obviously better than a slum, but a slum is better than none".[73]

Insufficient

Colonialism and segregation

Some of the slums in today's world are a product of

Others were created because of

Similarly, some of the slums of Lagos, Nigeria sprouted because of neglect and policies of the colonial era.[80] During apartheid era of South Africa, under the pretext of sanitation and plague epidemic prevention, racial and ethnic group segregation was pursued, people of colour were moved to the fringes of the city, policies that created Soweto and other slums – officially called townships.[81] Large slums started at the fringes of segregation-conscious colonial city centers of Latin America.[82] Marcuse suggests ghettoes in the United States, and elsewhere, have been created and maintained by the segregationist policies of the state and regionally dominant group.[83][84]

Poor infrastructure, social exclusion and economic stagnation

Social exclusion and poor infrastructure forces the poor to adapt to conditions beyond his or her control. Poor families that cannot afford transportation, or those who simply lack any form of affordable public transportation, generally end up in squat settlements within walking distance or close enough to the place of their formal or informal employment.[70] Ben Arimah cites this social exclusion and poor infrastructure as a cause for numerous slums in African cities.[67] Poor quality, unpaved streets encourage slums; a 1% increase in paved all-season roads, claims Arimah, reduces slum incidence rate by about 0.35%. Affordable public transport and economic infrastructure empowers poor people to move and consider housing options other than their current slums.[86][87]

A growing economy that creates jobs at rate faster than population growth, offers people opportunities and incentive to relocate from poor slum to more developed neighborhoods. Economic stagnation, in contrast, creates uncertainties and risks for the poor, encouraging people to stay in the slums. Economic stagnation in a nation with a growing population reduces per capita disposal income in urban and rural areas, increasing urban and rural poverty. Rising rural poverty also encourages migration to urban areas. A poorly performing economy, in other words, increases poverty and rural-to-urban migration, thereby increasing slums.[88][89]

Informal economy

Many slums grow because of growing informal economy which creates demand for workers. Informal economy is that part of an economy that is neither registered as a business nor licensed, one that does not pay taxes and is not monitored by local, state, or federal government.[90] Informal economy grows faster than formal economy when government laws and regulations are opaque and excessive, government bureaucracy is corrupt and abusive of entrepreneurs, labour laws are inflexible, or when law enforcement is poor.[91] Urban informal sector is between 20 and 60% of most developing economies' GDP; in Kenya, 78 per cent of non-agricultural employment is in the informal sector making up 42 per cent of GDP.[1] In many cities the informal sector accounts for as much as 60 per cent of employment of the urban population. For example, in Benin, slum dwellers comprise 75 per cent of informal sector workers, while in Burkina Faso, the Central African Republic, Chad and Ethiopia, they make up 90 per cent of the informal labour force.[92] Slums thus create an informal alternate economic ecosystem, that demands low paid flexible workers, something impoverished residents of slums deliver. In other words, countries where starting, registering and running a formal business is difficult, tend to encourage informal businesses and slums.[93][94][95] Without a sustainable formal economy that raise incomes and create opportunities, squalid slums are likely to continue.[96]

The World Bank and UN Habitat estimate, assuming no major economic reforms are undertaken, more than 80% of additional jobs in urban areas of developing world may be low-paying jobs in the informal sector. Everything else remaining same, this explosive growth in the informal sector is likely to be accompanied by a rapid growth of slums.[1]

Labour, work

Research in the latest years based on ethnographic studies, conducted since 2008 about slums, published initially in 2017, has found out the primary importance of labour as the main cause of emergence, rural-urban migration, consolidation and growth of informal settlements.[97][98] It also showed that work has also a crucial role in the self-construction of houses, alleys and overall informal planning of slums, as well as constituting a central aspect by residents living in slums when their communities suffer upgrading schemes or when they are resettled to formal housing.[97]

For example, it was recently proved that in a small favela in the northeast of Brazil (Favela Sururu de Capote), the migration of dismissed sugar cane factory workers to the city of Maceió (who initiated the self-construction of the favela), has been driven by the necessity to find a job in the city.[98] The same observation was noticed on the new migrants who contribute to the consolidation and growth of the slum. Also, the choice of the terrain for the construction of the favela (the margins of a lagoon) followed the rationale that it could offer conditions to provide them means of work. Circa 80% of residents living in that community live from the fishery of a mussel which divides the community through gender and age.[98] Alleys and houses were planned to facilitate the working activities, that provided subsistence and livelihood to the community. When resettled, the main reason of changes of formal housing units was due to the lack of possibilities to perform their work in the new houses designed according to formal architecture principles, or even by the distances they had to travel to work in the slum where they originally lived, which was in turn faced by residents by self-constructing spaces to shelter the work originally performed in the slum, in the formal housing units.[97] Similar observations were made in other slums.[97] Residents also reported that their work constitutes their dignity, citizenship, and self-esteem in the underprivileged settings in which they live.[97] The reflection of this recent research was possible due to participatory observations and the fact that the author of the research has lived in a slum to verify the socioeconomic practices which were prone to shape, plan and govern space in slums.[97]

Poverty

Urban poverty encourages the formation and demand for slums.[3] With rapid shift from rural to urban life, poverty migrates to urban areas. The urban poor arrives with hope, and very little of anything else. They typically have no access to shelter, basic urban services and social amenities. Slums are often the only option for the urban poor.[99]

Politics

Many local and national governments have, for political interests, subverted efforts to remove, reduce or upgrade slums into better housing options for the poor.[12] Throughout the second half of the 19th century, for example, French political parties relied on votes from slum population and had vested interests in maintaining that voting block. Removal and replacement of slum created a conflict of interest, and politics prevented efforts to remove, relocate or upgrade the slums into housing projects that are better than the slums. Similar dynamics are cited in favelas of Brazil,[100] slums of India,[101][102] and shanty towns of Kenya.[103]

Scholars[12][104] claim politics also drives rural-urban migration and subsequent settlement patterns. Pre-existing patronage networks, sometimes in the form of gangs and other times in the form of political parties or social activists, inside slums seek to maintain their economic, social and political power. These social and political groups have vested interests to encourage migration by ethnic groups that will help maintain the slums, and reject alternate housing options even if the alternate options are better in every aspect than the slums they seek to replace.[102][105]

Social conflicts

Millions of Lebanese people formed slums during the Lebanese Civil War from 1975 to 1990.[106][107] Similarly, in recent years, numerous slums have sprung around Kabul to accommodate rural Afghans escaping Taliban violence.[108]

Natural disasters

Major natural disasters in poor nations often lead to migration of disaster-affected families from areas crippled by the disaster to unaffected areas, the creation of temporary tent city and slums, or expansion of existing slums.[109] These slums tend to become permanent because the residents do not want to leave, as in the case of slums near Port-au-Prince after the 2010 Haiti earthquake,[110][111] and slums near Dhaka after 2007 Bangladesh Cyclone Sidr.[112]

Slums in developing countries

Location and growth

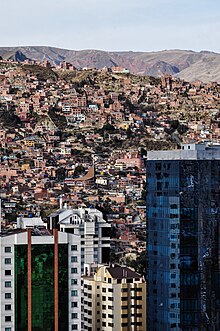

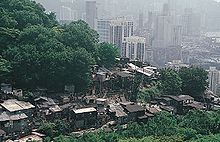

Slums typically begin at the outskirts of a city. Over time, the city may expand past the original slums, enclosing the slums inside the urban perimeter. New slums sprout at the new boundaries of the expanding city, usually on publicly owned lands, thereby creating an urban sprawl mix of formal settlements, industry, retail zones and slums. This makes the original slums valuable property, densely populated with many conveniences attractive to the poor.[113]

At their start, slums are typically located in the least desirable lands near the town or city, that are state owned, are part of a philanthropic trust, possessed by a religious entity, or have no clear land title. In cities located in mountainous terrain, slums begin on difficult to reach slopes or start at the bottom of flood prone valleys, often hidden from the plain view of downtown but close to some natural water source.[113] In cities located near lagoons, marshlands and rivers, they start on banks or on stilts above water or the dry river bed; in flat terrain, slums begin on lands unsuitable for agriculture, near city trash dumps, next to railway tracks,[114] and other shunned undesirable locations.

These strategies shield slums from the risk of being noticed and removed when they are small and most vulnerable to local government officials. Initial homes tend to be tents and shacks that are quick to install, but as a slum grows, becomes established and newcomers pay the informal association or gang for the right to live in the slum, the construction materials for the slums switches to more durable materials such as bricks and concrete, suitable for slum's topography.[115][116]

The original slums, over time, get established next to centers of economic activity, schools, hospitals, and sources of employment, which the poor rely on.[97] Established old slums, surrounded by the formal city infrastructure, cannot expand horizontally; therefore, they grow vertically by stacking additional rooms, sometimes for a growing family and sometimes as a source of rent from new arrivals in slums.[117] Some slums name themselves after founders of political parties, locally respected historical figures, current politicians or a politician's spouse to garner political backing against eviction.[118]

Insecure tenure

Informality of

Secure land tenure is important for slum dwellers as an authentic recognition of their residential status in urban areas. It also encourages them to upgrade their housing facilities, which will give them protection against natural and unnatural hazards.

Substandard housing and overcrowding

Slum areas are characterized by substandard housing structures.[126][127] Shanty homes are often built hurriedly, on ad hoc basis, with materials unsuitable for housing. Often the construction quality is inadequate to withstand heavy rains, high winds, or other local climate and location. Paper, plastic, earthen floors, mud-and-wattle walls, wood held together by ropes, straw or torn metal pieces as roofs are some of the materials of construction. In some cases, brick and cement is used, but without attention to proper design and structural engineering requirements.[128] Various space, dwelling placement bylaws and local building codes may also be extensively violated.[3][129]

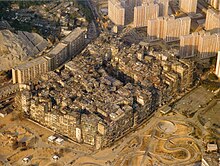

Overcrowding is another characteristic of slums. Many dwellings are single room units, with high occupancy rates. Each dwelling may be cohabited by multiple families. Five and more persons may share a one-room unit; the room is used for cooking, sleeping and living. Overcrowding is also seen near sources of drinking water, cleaning, and sanitation where one toilet may serve dozens of families.[130][131][132] In a slum of Kolkata, India, over 10 people sometimes share a 45 m2 room.[133] In Kibera slum of Nairobi, Kenya, population density is estimated at 2,000 people per hectare — or about 500,000 people in one square mile.[134]

However, the density and neighbourhood effects of slum populations may also offer an opportunity to target health interventions.[135]

Inadequate or no infrastructure

One of the identifying characteristics of slums is the lack of or inadequate public infrastructure.

Slums often have very narrow alleys that do not allow vehicles (including

In many countries, local and national government often refuse to recognize slums, because the slum are on disputed land, or because of the fear that quick official recognition will encourage more slum formation and seizure of land illegally. Recognizing and notifying slums often triggers a creation of property rights, and requires that the government provide public services and infrastructure to the slum residents.[142][143] With poverty and informal economy, slums do not generate tax revenues for the government and therefore tend to get minimal or slow attention. In other cases, the narrow and haphazard layout of slum streets, houses and substandard shacks, along with persistent threat of crime and violence against infrastructure workers, makes it difficult to layout reliable, safe, cost effective and efficient infrastructure. In yet others, the demand far exceeds the government bureaucracy's ability to deliver.[144][145]

Low socioeconomic status of its residents is another common characteristic attributed to slum residents.[146]

Problems

Vulnerability to natural and man-made hazards

Slums are often placed in areas vulnerable to natural disasters such as

Some slums risk

Unemployment and informal economy

Due to lack of skills and education as well as competitive job markets,[157] many slum dwellers face high rates of unemployment.[158] The limit of job opportunities causes many of them to employ themselves in the informal economy, inside the slum or in developed urban areas near the slum. This can sometimes be licit informal economy or illicit informal economy without working contract or any social security. Some of them are seeking jobs at the same time and some of those will eventually find jobs in formal economies after gaining some professional skills in informal sectors.[157]

Examples of licit informal economy include street vending, household enterprises, product assembly and packaging, making garlands and embroideries, domestic work, shoe polishing or repair, driving tuk-tuk or manual rickshaws, construction workers or manually driven logistics, and handicrafts production.[159][160][98] In some slums, people sort and recycle trash of different kinds (from household garbage to electronics) for a living – selling either the odd usable goods or stripping broken goods for parts or raw materials.[98] Typically these licit informal economies require the poor to regularly pay a bribe to local police and government officials.[161]

Examples of illicit informal economy include illegal substance and weapons trafficking, drug or moonshine/changaa production, prostitution and gambling – all sources of risks to the individual, families and society.[163][164][165] Recent reports reflecting illicit informal economies include drug trade and distribution in Brazil's favelas, production of fake goods in the colonías of Tijuana, smuggling in katchi abadis and slums of Karachi, or production of synthetic drugs in the townships of Johannesburg.[166]

The slum-dwellers in informal economies run many risks. The informal sector, by its very nature, means income insecurity and lack of social mobility. There is also absence of legal contracts, protection of labour rights, regulations and bargaining power in informal employments.[167]

Violence

Some scholars suggest that crime is one of the main concerns in slums.[168] Empirical data suggest crime rates are higher in some slums than in non-slums, with slum homicides alone reducing life expectancy of a resident in a Brazil slum by 7 years than for a resident in nearby non-slum.[7][169] In some countries like Venezuela, officials have sent in the military to control slum criminal violence involved with drugs and weapons.[170] Rape is another serious issue related to crime in slums. In Nairobi slums, for example, one fourth of all teenage girls are raped each year.[171]

On the other hand, while UN-Habitat reports some slums are more exposed to

Slum crime rate correlates with insufficient

Women in slums are at greater risk of physical and sexual violence.[175] Factors such as unemployment that lead to insufficient resources in the household can increase marital stress and therefore exacerbate domestic violence.[176]

Slums are often non-secured areas and women often risk sexual violence when they walk alone in slums late at night. Violence against women and women's security in slums emerge as recurrent issues.[177]

Another prevalent form of violence in slums is armed violence (gun violence), mostly existing in African and Latin American slums. It leads to homicide and the emergence of criminal gangs.[178] Typical victims are male slum residents.[179][180] Violence often leads to retaliatory and vigilante violence within the slum.[181] Gang and drug wars are endemic in some slums, predominantly between male residents of slums.[182][183] The police sometimes participate in gender-based violence against men as well by picking up some men, beating them and putting them in jail. Domestic violence against men also exists in slums, including verbal abuses and even physical violence from households.[183]

Cohen as well as Merton theorized that the cycle of slum violence does not mean slums are inevitably criminogenic, rather in some cases it is frustration against life in slum, and a consequence of denial of opportunity to slum residents to leave the slum.[184][185][186] Further, crime rates are not uniformly high in world's slums; the highest crime rates in slums are seen where illicit economy – such as drug trafficking, brewing, prostitution and gambling – is strong and multiple gangs are fighting for control.[187][188]

Infectious diseases and epidemics

Slum dwellers usually experience a high rate of disease.

Factors that have been attributed to a higher rate of disease transmission in slums include high

Slums have been historically linked to epidemics, and this trend has continued in modern times.[211][212][213] For example, the slums of West African nations such as Liberia were crippled by as well as contributed to the outbreak and spread of Ebola in 2014.[214][215] Slums are considered a major public health concern and potential breeding grounds of drug resistant diseases for the entire city, the nation, as well as the global community.[216][217]

Child malnutrition

Child malnutrition is more common in slums than in non-slum areas.[218] In

The major nutritional problems in slums are

Widespread child malnutrition in slums is closely related to family

Other non-communicable diseases

A multitude of non-contagious diseases also impact health for slum residents. Examples of prevalent non-infectious diseases include: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, neurological disorders, and mental illness.[225] In some slum areas of India, diarrhea is a significant health problem among children. Factors like poor sanitation, low literacy rates, and limited awareness make diarrhea and other dangerous diseases extremely prevalent and burdensome on the community.[226]

Lack of reliable data also has a negative impact on slum dwellers' health. A number of slum families do not report cases or seek professional medical care, which results in insufficient data.

Overall, a complex network of physical, social, and environmental factors contribute to the health threats faced by slum residents.[232]

Countermeasures

Recent years have seen a dramatic growth in the number of slums as urban populations have increased in

Some NGO's are focused at addressing local problems (i.e. sanitation issues, health, ...), through the mapping out of the slums and its health services,[234] creation of latrines,[235] creation of local food production projects, and even microcredit projects.[236] In one project (in Rio de Janeiro), the government even employed slum residents for the reforestation of a nearby location.[237][238]

To achieve the goal of "cities without slums", the UN claims that governments must undertake vigorous urban planning, city management, infrastructure development, slum upgrading and poverty reduction.[13]

Slum removal

Some city and state officials have simply sought to remove slums.[241][242] This strategy for dealing with slums is rooted in the fact that slums typically start illegally on someone else's land property, and they are not recognized by the state. As the slum started by violating another's property rights, the residents have no legal claim to the land.[243][244]

Critics argue that slum removal by force tend to ignore the social problems that cause slums. The poor children as well as working adults of a city's informal economy need a place to live. Slum clearance removes the slum, but it does not remove the causes that create and maintain the slum.[245][246] Policymakers, urban planners, and politicians need to take the factors that cause people to live in informal housing into consideration while tackling the issue of slums.[247]

Slum relocation

Slum relocation strategies rely on removing the slums and relocating the slum poor to free semi-rural peripheries of cities, sometimes in free housing. An example of this is the governmental program in Morocco called Cities without Shantytowns (sometimes referred to as Cities without Slums or, in French, Villes Sans Bidonvilles), which was launched to put an end to informal housing and resettle the communities in slums into apartments.[247]

This strategy ignores several dimensions of a slum life. The strategy sees slum as merely a place where the poor lives. In reality, slums are often integrated with every aspect of a slum resident's life, including sources of employment, distance from work, and social life.[248] Slum relocation that displaces the poor from opportunities to earn a livelihood, generates economic insecurity in the poor.[249] In some cases, the slum residents oppose relocation even if the replacement land and housing to the outskirts of cities is of better quality than their current house. Examples include Zone One Tondo Organization of Manila, Philippines, and Abahlali base Mjondolo of Durban, South Africa.[250] In other cases, such as Ennakhil slum relocation project in Morocco, systematic social mediation has worked. The slum residents have been convinced that their current location is a health hazard, prone to natural disaster, or that the alternative location is well connected to employment opportunities.[251]

Slum upgrading

Some governments have begun to approach slums as a possible opportunity to urban development by slum upgrading. This approach was inspired in part by the theoretical writings of John Turner in 1972.[252][253] The approach seeks to upgrade the slum with basic infrastructure such as sanitation, safe drinking water, safe electricity distribution, paved roads, rain water drainage system, and bus/metro stops.[254] The assumption behind this approach is that if slums are given basic services and tenure security – that is, the slum will not be destroyed and slum residents will not be evicted, then the residents will rebuild their own housing, engage their slum community to live better, and over time attract investment from government organizations and businesses. Turner argued not to demolish the housing, but to improve the environment: if governments can clear existing slums of unsanitary human waste, polluted water and litter, and from muddy unlit lanes, they do not have to worry about the shanty housing.[255] "Squatters" have shown great organizational skills in terms of land management, and they will maintain the infrastructure that is provided.[255]

In

Most slum upgrading projects, however, have produced mixed results. While initial evaluations were promising and success stories widely reported by media, evaluations done 5 to 10 years after a project completion have been disappointing. Herbert Werlin[255] notes that the initial benefits of slum upgrading efforts have been ephemeral. The slum upgrading projects in kampungs of Jakarta, Indonesia, for example, looked promising in first few years after upgrade, but thereafter returned to a condition worse than before, particularly in terms of sanitation, environmental problems and safety of drinking water. Communal toilets provided under slum upgrading effort were poorly maintained, and abandoned by slum residents of Jakarta.[257] Similarly slum upgrading efforts in Philippines,[258][259] India[260] and Brazil[261][262] have proven to be excessively more expensive than initially estimated, and the condition of the slums 10 years after completion of slum upgrading has been slum like. The anticipated benefits of slum upgrading, claims Werlin, have proven to be a myth.[255] There is limited but consistent evidence that slums upgrading may prevent diarrhoeal diseases and water-related expenditure.[263]

Slum upgrading is largely a government controlled, funded and run process, rather than a competitive market driven process. Krueckeberg and Paulsen note[264] conflicting politics, government corruption and street violence in slum regularization process is part of the reality. Slum upgrading and tenure regularization also upgrade and regularize the slum bosses and political agendas, while threatening the influence and power of municipal officials and ministries. Slum upgrading does not address poverty, low paying jobs from informal economy, and other characteristics of slums.[97] Recent research shows that the lack of these options make residents to undertake measures to assure their working needs.[98] One example in the northeast of Brazil, Vila S. Pedro, was mischaracterized by informal self-constructions by residents to restore working opportunities originally employed in the informal settlement.[97] It is unclear whether slum upgrading can lead to long-term sustainable improvement to slums.[265]

Urban infrastructure development and public housing

Urban infrastructure such as reliable high speed mass transit system, motorways/interstates, and public housing projects have been cited[266][267] as responsible for the disappearance of major slums in the United States and Europe from the 1960s through 1970s. Charles Pearson argued in UK Parliament that mass transit would enable London to reduce slums and relocate slum dwellers. His proposal was initially rejected for lack of land and other reasons; but Pearson and others persisted with creative proposals such as building the mass transit under the major roads already in use and owned by the city. London Underground was born, and its expansion has been credited to reducing slums in respective cities[268] (and to an extent, the New York City Subway's smaller expansion).[269]

As cities expanded and business parks scattered due to cost ineffectiveness, people moved to live in the suburbs; thus retail, logistics, house maintenance and other businesses followed demand patterns. City governments used infrastructure investments and urban planning to distribute work, housing, green areas, retail, schools and population densities. Affordable public mass transit in cities such as New York City, London and Paris allowed the poor to reach areas where they could earn a livelihood. Public and council housing projects cleared slums and provided more sanitary housing options than what existed before the 1950s.[270]

Slum clearance became a priority policy in Europe between 1950–1970s, and one of the biggest state-led programs. In the UK, the slum clearance effort was bigger in scale than the formation of

The US and European governments additionally created a procedure by which the poor could directly apply to the government for housing assistance, thus becoming a partner to identifying and meeting the housing needs of its citizens.[272][273] One historically effective approach to reduce and prevent slums has been citywide infrastructure development combined with affordable, reliable public mass transport and public housing projects.[274]

However, slum relocation in the name of urban development is criticized for uprooting communities without consultation or consideration of ongoing livelihood. For example, the Sabarmati Riverfront Project, a recreational development in Ahmedabad, India, forcefully relocated over 19,000 families from shacks along the river to 13 public housing complexes that were an average of 9 km away from the family's original dwelling.[275]

Prevalence

Slums exist in many countries and have become a global phenomenon.[277] A UN-Habitat report states that in 2006 there were nearly 1 billion people settling in slum settlements in most cities of Central America, Asia, South America and Africa, and a smaller number in the cities of Europe and North America.[278]

In 2012, according to UN-Habitat, about 863 million people in the

The distribution of slums within a city varies throughout the world. In most of the

In some cities, especially in countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, slums are not just marginalized neighborhoods holding a small population; slums are widespread, and are home to a large part of urban population. These are sometimes called slum cities.[280]

The percentage of developing world's urban population living in slums has been dropping with economic development, even while total urban population has been increasing. In 1990, 46 percent of the urban population lived in slums; by 2000, the percentage had dropped to 39%; which further dropped to 32% by 2010.[281]

See also

Variations of impoverished settlements

- Banlieue (Term used for the deprived neighbourhoods in the edges or around the French cities)

- Barrio (slums in Venezuela)

- Campamento (slums in Chile)

- Favela (slums in Brazil)

- Gecekondu (slums in Turkey)

- Ghetto

- Hooverville (slums in 1930s US)

- Inner city

- Komboni (slums in Zambia)

- Pueblos jóvenes (slums in Peru)

- Refugee shelter

- Romani Peoplecamp

- Rooftop slum

- Rookery (slums in London, United Kingdom)

- Shanty town

- Skid row

- Tent city

- Trailer park

- Urban village (China)

- Villa miseria (slums in Argentina)

References

- ^ a b c d e f g What are slums and why do they exist? Archived 2011-02-06 at the Wayback Machine UN-Habitat, Kenya (April 2007)

- ISBN 9780415252256.

- ^ a b c UN-HABITAT 2007 Press Release Archived 2011-02-06 at the Wayback Machine on its report, "The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements 2003".

- ^ ISBN 978-0674025752

- ^ PMC 2588079.

- ^ Slums: Past, Present and Future United Nations Habitat (2007)

- ^ a b c d e The challenge of slums – Global report on Human Settlements, United Nations Habitat (2003)

- ISBN 978-2-7071-4915-2)

- ^ 5 Biggest Slums in the World Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine, International Business Times, Daniel Tovrov, IB Times (December 9, 2011)

- ISBN 978-0-345-54711-8; see page 277

- ^ Patton, C. (1988). Spontaneous shelter: International perspectives and prospects, Philadelphia: Temple University Press

- ^ a b c Assessing Slums in the Development Context Archived 2014-01-05 at the Wayback Machine United Nations Habitat Group (2011)

- ^ a b c Slum Dwellers to double by 2030 Archived 2013-03-17 at the Wayback Machine UN-HABITAT report, April 2007.

- ^ Local Government Actions to Reduce Poverty and Achieve The Millennium Development Goals Archived 2019-10-22 at the Wayback Machine, Mona Serageldin, Elda Solloso, and Luis Valenzuela, Global Urban Development Magazine, Vol 2, Issue 1 (March 2006)

- ^ "Population living in slums". United Nations. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ Slum Archived 2014-02-03 at the Wayback Machine Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper (2001)

- ISBN 92-1-131683-9, UN-Habitat; page 30

- S2CID 220803082.

- ^ Flanders, Judith (May 15, 2014) "Discovering Literature: Romantics & Victorians: Slums" British Library

- ^ Unearthing Manchester's Victorian slums Archived 2016-09-20 at the Wayback Machine Mike Pitts, The Guardian (August 27, 2009)

- ^ The History of Council Housing Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine University of the West of England, Bristol (2008)

- ^ Eckstein, Susan. 1990. Urbanization Revisited: Inner-City Slum of Hope and Squatter Settlement of Despair. World Development 18: 165–181

- ISBN 978-0415252256, (page 410); also see Encyclopædia Britannica (2001), article on Slum

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-28848-4.

- ISBN 978-0-559-68852-2.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ISBN 978-0-521-28848-4.

cardinal wiseman slum.

- ISBN 978-0-7658-0870-7.

- ^ Toronto Culture – Exploring Toronto's past – The First Half of the 20th Century, 1901–51 City of Toronto, Ontario, Canada (2011)

- ^ "Remembering St. John's Ward: The Images of Toronto City Photographer, Arthur S. Goss". Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Nancy Krieger, Historical roots of social epidemiology, Int. Journal Epidemiol. (2001) 30 (4): 899–900

- ISBN 978-0299098803

- ^ 10 idées reçues sur les HLM Archived 2013-11-26 at the Wayback Machine, Union sociale pour l'habitat, February 2012

- ^ France – public housing Archived 2013-05-18 at the Wayback Machine European Union

- ^ Ordering the Disorderly Slum – Standardizing Quality of Life in Marseille Tenements and Bidonvilles Archived 2016-10-14 at the Wayback Machine Minayo Nasiali, Journal of Urban History November 2012 vol. 38 no. 6, 1021–1035

- ^ Livret A rate falls to 1.25% Archived 2013-08-22 at the Wayback Machine The Connexion (July 18, 2013)

- ^ "Paris: Le bidonville de la Petite ceinture évacué".

- ^ a b c The First Slum in America Archived 2016-12-06 at the Wayback Machine Kevin Baker, The New York Times (September 30, 2001)

- ^ Solis, Julia. New York Underground: The Anatomy of a City. p. 76

- ^ Suttles, Gerald D. 1968. The Social Order of the Slum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- ^ Gans, Herbert J. 1962. The Urban Villagers. New York: The Free Press

- ^ HISTORY OF US PUBLIC HOUSING Archived 2014-02-23 at the Wayback Machine Affordable Housing Institute, United States (2008); See Part 1, 2 and 3

- ISBN 978-0226870236; see pages 45–61

- ^ Courgey (1908), Recherche et classement des anormaux: enquête sur les enfants des Écoles de la ville d'Ivry-sur-Seine, International Magazine of School Hygiene, Ed: Sir Lauder Brunton, 395–418

- ^ "Cités de transit": the urban treatment of poverty during decolonisation Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine Muriel Cohen & Cédric David, Metro Politiques (March 28, 2012)

- ^ Le dernier bidonville de Nice Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine Pierre Espagne, Reperes Mediterraneens (1976)

- ISBN 978-0520039520; pages 12–16

- ^ a b "International Medical Corps – International Medical Corps". Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Participating countries". Archived from the original on 2009-01-14. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ^ Machetes, Ethnic Conflict and Reductionism Archived 2008-05-19 at the Wayback Machine The Dominion

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-24. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Brazil: The Challenges in Becoming an Agricultural Superpower Archived 2013-10-23 at the Wayback Machine Geraldo Barros, Brookings Institution (2008)

- ^ Urban Poverty – An Overview Judy Baker, The World Bank (2008)

- ^ Tjiptoherijanto, Prinjono, and Eddy Hasmi. "Urbanization and Urban Growth in Indonesia." Asian Urbanization in the New Millennium. Ed. Gayl D. Ness and Prem P. Talwar. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Academic, 2005., page 162

- ^ a b Todaro, Michael P. (1969). "A Model of Labour Migration and Urban Unemployment in Less Developed Countries". The American Economic Review. 59 (1): 138–148.

- PMID 18016046.

- ^ Ali, Mohammed Akhter; Kavita Toran (2004). "Migration, Slums and Urban Squalor – A case study of Gandhinagar Slum". Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Environment and Health: 1–10.

- ^ a b Davis, Mike (2006). Planet of Slums. Verso.

- ^ State of the world population 2007: unleashing the potential of urban growth. New York: United Nations Population Fund. 2007.

- ^ S2CID 130682432.

- ^ S2CID 19545185.

- ^ S2CID 24793439.

- ^ Firdaus, Ghuncha (2012). "Urbanization, emerging slums and increasing health problems: a challenge before the nation: an empirical study with reference to state of uttar pradesh in India". Journal of Environmental Research and Management. 3 (9): 146–152.

- ^ JSTOR 3145522.

- ^ UN-HABITAT (2003b) The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements. Earthscan, London: UN-Habitat. 2003.

- ^ Wekwete, K. H (2001). "Urban management: The recent experience, in Rakodi, C.". The Urban Challenge in Africa.

- ^ Cheru, F (2005). Globalization and uneven development in Africa: The limits to effective urban governance in the provision of basic services. UCLA Globalization Research Center-Africa.

- ^ a b c d Slums as Expressions of Social Exclusion: Explaining the Prevalence of Slums in African Countries Archived 2013-10-15 at the Wayback Machine Ben Arimah, United Nations Human Settlements Programme, Nairobi, Kenya

- JSTOR 3145421.

- ^ S2CID 153400618.

- ^ a b c Istanbul's Gecekondus Archived 2013-10-22 at the Wayback Machine Orhan Esen, London School of Economics and Political Science (2009)

- ^ United Nations (2000). "United Nations Millennium Declaration" (PDF). United Nations Millennium Summit. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-03-07. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ^ .

- ^ Scourge of slums Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine The Economist (July 14, 2012)

- ^ .

- PMID 17387618.

- ^ a b Jan Nijman, A STUDY OF SPACE IN MUMBAI'S SLUMS, Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie Volume 101, Issue 1, pages 4–17, February 2010

- ISBN 978-0141000237, pages 3–11

- ^ Pacione, Michael (2006), Mumbai, Cities, 23(3), pages 229–238

- S2CID 154852140.

- ^ Liora Bigon, Between Local and Colonial Perceptions: The History of Slum Clearances in Lagos (Nigeria), 1924–1960, African and Asian Studies, Volume 7, Number 1, 2008, pages 49–76 (28)

- ^ Beinart, W., & Dubow, S. (Eds.), (2013), Segregation and apartheid in twentieth century South Africa, Routledge, pages 25–35

- ^ Griffin, E., and Ford, L. (1980), A model of Latin American city structure, Geographical Review, pages 397–422

- ^ Marcuse, Peter (2001), Enclaves yes, ghettoes, no: Segregation and the state Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Conference Paper, Columbia University

- ^ Bauman, John F (1987), Public Housing, Race, and Renewal: Urban Planning in Philadelphia, 1920–1974, Philadelphia, Temple University Press

- ^ Destroying Makoko Archived 2013-09-04 at the Wayback Machine The Economist (August 18, 2012)

- ^ Africa: Improved infrastructure key to slum upgrading – UN Official Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine IRIN, United Nations News Service (11 June 2009)

- ^ LATIN AMERICAN SLUM UPGRADING EFFORTS Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine Elisa Silva, Arthur Wheelwright Traveling Fellowship 2011, Harvard University

- ISBN 1-84407-037-9

- ^ Growing out of poverty: Urban job Creation and the Millennium Development Goals Archived 2019-10-31 at the Wayback Machine Marja Kuiper and Kees van der Ree, Global Urban Development Magazine, Vol 2, Issue 1, March 2006

- ^ "The Informal Economy: Fact Finding Study" (PDF). Department for Infrastructure and Economic Cooperation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ^ Towards a better understanding of informal economy Archived 2015-01-09 at the Wayback Machine Dan Andrews, Aida Caldera Sánchez, and Åsa Johansson, OECD France (30 May 2011)

- ^ The state of world's cities Archived 2009-07-04 at the Wayback Machine UN Habitat (2007)

- ^ The Urban Informal Sector in Nigeria Archived 2013-09-13 at the Wayback Machine Geoffrey Nwaka, Global Urban Development Magazine, Vol 1, No 1 (May 2005)

- ^ In nairobi's slums, problems and potential as big as Africa itself Archived 2015-01-09 at the Wayback Machine Sam Sturgis, Rockefeller Foundation, (January 3, 2013)

- ^ In one slum, misery, work, politics and hope Archived 2015-01-08 at the Wayback Machine Jim Yardley, New York Times (December 28, 2011)

- ^ Minnery et al., Slum upgrading and urban governance: Case studies in three South East Asian cities, Habitat International, Volume 39, July 2013, Pages 162–169

- ^ ISBN 9783868595345.

- ^ JSTOR 44779812.

- ISBN 92-1-131683-9, UN-Habitat

- ^ The case of São Paulo, Brazil – Slums Archived 2016-03-06 at the Wayback Machine Mariana Fix, Pedro Arantes and Giselle Tanaka, Laboratorio de Assentamentos Humanos de FAU-USP, São Paulo, pages 15–20

- ^ Bid to develop Indian slum draws opposition Archived 2018-11-06 at the Wayback Machine Philip Reeves, National Public Radio (Washington DC), May 9, 2007

- ^ a b Slum banged Archived 2014-08-08 at the Wayback Machine Joshi and Unnithan, India Today (March 7, 2005)

- ^ An Inventory of the Slums in Nairobi Archived 2013-08-10 at the Wayback Machine Irene Wangari Karanja and Jack Makau, IRIN, United Nations News Service (2010); page 10-14

- ISBN 978-0226781921, University of Chicago Press, see Chapter 1

- ^ Bright City Lights and Slums of Dhaka city Archived 2013-05-07 at the Wayback Machine Ahsan Ullah, City University of Hong Kong (2002)

- ^ Slums – Summary of City Case Studies Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine UN Habitat, page 203

- ^ Slums: The case of Beirut, Lebanon Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine, Mona Fawaz and Isabelle Peillen, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2003)

- ^ Fleeing war, finding misery The plight of the internally displaced in Afghanistan Archived 2018-11-22 at the Wayback Machine Amnesty International (February 2012); page 9-12

- ^ Slum upgrading – Why do slums develop Archived 2013-09-06 at the Wayback Machine Cities Alliance (2011)

- ^ Three years after Haiti earthquake, loss of hope, desperation Archived 2013-10-03 at the Wayback Machine Jacqueline Charles, Miami Herald (January 8, 2013)

- ^ Slum eviction plans in Haiti spark protests Archived 2018-11-03 at the Wayback Machine The Telegraph (United Kingdom), July 25, 2012

- ^ Bangladesh cyclone: Rebuilding after Cyclone Sidr Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Habitat for Humanity International (May 6, 2009)

- ^ a b c d e f Rosa Flores Fernandez (2011), Physical and Spatial Characteristics of Slum Territories Vulnerable to Natural Disasters Archived 2013-10-20 at the Wayback Machine, Les Cahiers d'Afrique de l'Est, n° 44, French Institute for Research in Africa

- ^ a b Banerji, M. (2009), Provision of basic services in the slums and resettlement colonies of Delhi, Institute of Social Studies Trust

- ISBN 978-0719007071

- ^ McAuslan, Patrick. (1986). Les mal logés du Tiers-Monde. Paris: Éditions L'Harmattan

- ^ Centre des Nations Unies pour les Etablissements Humains (CNUEH). (1981). Amélioration physique des taudis et des bidonvilles Archived 2014-11-01 at the Wayback Machine, Nairobi

- ^ Gilbert, Daniel (1990), Barriada Haute-Espérance : Récit d'une coopération au Pérou. Paris: Éditions Karthala

- ^ a b Agbola, Tunde; Elijah M. Agunbiade (2009). "Urbanization, Slum Development and Security of Tenure- The Challenges of Meeting Millennium Development Goal 7 in Metropolitan Lagos, Nigeria". Urban Population–Development–Environment Dynamics in the Developing World- Case Studies and Lessons Learned: 77–106.

- (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- Davy, Ben; Sony Pellissery (2013). "The citizenship promise (un) fulfilled: The .

- ^ Flood, Joe (2006). "Secure Tenure Survey Final Report". Urban Growth Management Initiative.

- ^ Taschner, Suzana (2001), Desenhando os espaços da pobreza. Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Université de Sao Paulo

- .

- .

- ^ Ravetz, A. (2013). The government of space: town planning in modern society. Routledge

- JSTOR 3159005.

- .

- JSTOR 1287349.

- ISBN 1-84407-037-9[page needed]

- PMID 17551841.

- .

- ^ Wohl, A. S. (1977). The Eternal Slum: Housing and Social Policy in Victorian (Vol. 5). Transaction Books.

- ^ Kundu N (2003) Urban slum reports: The case of Kolkata, India. Nairobi: United Nations

- ^ Integrated Water Sanitation and Waste Management in Kibera Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine United Nations (2008)

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- ^ Kenya Slum Upgrading Project United Nations Habitat (2011)

- ^ Slums in Romania Archived 2015-06-10 at the Wayback Machine Cristina Iacoboaea (2009), TERUM, No 1, Vol 10, pages 101–113

- ^ Growth of Slums, Availability of Infrastructure and Demographic Outcomes in Slums: Evidence from India[permanent dead link] S Chandrasekhar (2005), Urbanization in Developing Countries at the Population Association of America, Philadelphia

- ^ The unlisted: how people without an address are stripped of their basic rights Archived 2020-03-28 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, 2020

- ^ Chasant, Muntaka (23 December 2018). "Sodom And Gomorrah (Agbogbloshie) - Ghana". ATC MASK. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Matt Birkinshaw, Abahlali baseMjondolo Movement SA. August 2008. Big Devil in the Jondolos: The Politics of Shack Fires. Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

- PMID 23400338.

- .

- )

- PMID 17387618.

- ^ "Slums of Urban Bangladesh: Mapping and Census, 2005". Archived from the original on 2013-06-22. Retrieved 2012-09-05.

- ^ Rio slum landslide leaves hundreds dead Archived 2017-05-04 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian (8 April 2010)

- ^ Dilley, M. (2005). Natural disaster hotspots: a global risk analysis (Vol. 5). World Bank Publications

- ]

- ]

- .

- S2CID 155074833.

- ^ ]

- ^ "3 dead as massive fire breaks out at outer Delhi slum". Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Photos: Manila slum fire leaves more than 1,000 homeless". 2013-07-11. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- .

- ^ a b Gupta, Indrani; Arup Mitra (2002). "Rural migrants and labour segmentation: Micro-level evidence from Delhi slums". Economic and Political Weekly: 163–168.

- ^ Slum residence Archived 2013-10-05 at the Wayback Machine World Health Organization (2010)

- ^ Taj Ganj Slum Housing Archived 2013-11-27 at the Wayback Machine, Cities Alliance (2012)

- ISBN 978-951-22-9102-1

- ^ The case of Karachi, Pakistan Archived 2011-04-09 at the Wayback Machine Urban Slum Reports, A series on Slums of the World (2011); see page 13

- ^ How New York City Sold Public Housing Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Mark Byrnes, The Atlantic (November 2, 2011)

- ^ Uganda: slum areas, posh pubs biggest drug hubs Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine All Africa News (January 7, 2013)

- The Economist. 2010-04-29.

- ISBN 978-0815328735, page 29

- ^ Vanda Felbab-Brown, Bringing the State to the Slum: Confronting Organized Crime and Urban Violence in Latin America – Lessons for Law Enforcement and Policymakers Archived 2014-03-07 at the Wayback Machine Brookings Institution (December 2011)

- ^ Breman, J. (2003). The labouring poor in India: Patterns of exploitation, subordination, and exclusion. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- PMID 24382935.

- ^ In the Violent Favelas of Brazil Archived 2013-09-17 at the Wayback Machine S Mehta, The New York Review of Books (August 2013)

- ^ Venezuela's military enters high crime slums Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine Karl Ritter, Associated Press (May 17, 2013)

- ^ Newar, Rachel (14 June 2013). "In Kenya, Where One in Four Women has Been Raped, Self Defense Training Makes a Difference". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Global: Urban conflict – fighting for resources in the slums Archived 2013-11-05 at the Wayback Machine IRIN, United Nations News Service (October 8, 2007)

- ^ Josephine Slater (2009), Naked C

- ^ Bringing the State to the Slum: Confronting Organized Crime and Urban Violence in Latin America Archived 2013-10-05 at the Wayback Machine Vanda Felbab-Brown (2011), Brookings Institution

- S2CID 1041409.

- .

- ISBN 978-92-95004-42-9.

- ^ Palus, Nancy. "Humanitarian intervention in violence-hit slums – from whether to how". IRIN. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 1 Nov 2013.

- ^ More Slums Equals More Violence Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine Robert Muggah and Anna Alvazzi del Frate, Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development & UNDP (October 2007)

- hdl:10520/EJC93065.

- S2CID 153350971.

- OCLC 855972637.

- ^ a b Ochako, Rhoune Adhiambo; et al. (2011). "Gender-Based Violence in the Context of Urban Poverty: Experiences of Men from the Slums of Nairobi, Kenya". Population Association of America 2011 Annual Meeting Program.

- JSTOR 2084686.

- ^ S Cohen (1971), Images of deviance, Harmondsworth, UK, Penguin

- ISBN 978-1412981453, pages 41-69

- ^ Global: Urban conflict - fighting for resources in the slums Archived 2013-11-05 at the Wayback Machine IRIN, United Nations News Service (October 8, 2007)

- ISBN 0-9550664-3-3

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- ^ Nossiter, Adam (2012-08-22). "Cholera Epidemic Envelops Coastal Slums in West Africa". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 20 Nov 2013.

- ^ Cholera epidemic envelops coastal slums in West Africa, Africa Health[permanent dead link], page 10 (September 2012)

- PMID 22591621.

- PMID 22704913.

- ^ MEASLES OUTBREAK – A STUDY IN MIGRANT POPULATION IN ALIGARH[permanent dead link] Najam Khalique et al, Indian J. Prev. Soc. Med. Vol. 39 No.3& 4 2008

- PMID 23721247.

- PMID 23222946.

- PMID 23497202.

- PMID 22824498.

- ^ India: Battling TB in India's slums The World bank (May 9, 2013)

- PMID 19732423.

- PMID 21072238.

- ^ PMID 15964861.

- PMID 18299707.

- PMID 19070950.

- S2CID 5608709.

- PMID 26981732.

- PMID 18331630. Slums can also cause the disease of blackening of the body which is known as "Black Bund"

- (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- ^ World Health Organization (2004). Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Links to Health: Facts and Figures.[page needed]

- PMID 15964861.

- ISBN 981-04-0164-7

- S2CID 55748580.

- S2CID 17297343.

- ^ In a Liberian slum swarming with Ebola, a race against time to save two little girls Archived 2018-02-01 at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post

- ^ Liberian Slum Takes Ebola Treatment Into Its Own Hands Archived 2014-11-01 at the Wayback Machine The Wall Street Journal

- ISBN 978-0-470-42206-9

- PMID 21272793.

- ^ from the original on 2018-03-22. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ^ Dasra. "Nourishing our Future: Tackling Child Malnutrition in Urban Slums".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ PMID 12693602.

- ^ United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2006). State of the world's cities 2006/7. London: Earthscan Publications.[page needed]

- ^ Karim, Md Rezaul (11 Jan 2012). "Children suffering malnutrition in a slum". Wikinut-guides-activism.

- ^ Punwani, Jyoti (Jan 10, 2011). "Malnutrition kills 56,000 children annually in urban slums". The Times of India. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- PMID 14700351.

- PMID 30270904.

- PMID 21261200.

- ^ Desai, V.K.; el al. (2003). "Study of measles incidence and vaccination coverage in slums of Surat city". Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 28 (1).

- ^ PMID 17343758.

- from the original on 2018-10-12. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- PMID 16624184.

- (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- PMID 28170319.

- ISBN 978-1-907121-02-9; page 14

- ^ Slummapping

- S2CID 132760561.

- ^ About Liveinslums

- ^ Reforestation in Rio: More birds, less greenhouse gases, safer favelas

- ^ An opportunity to break barriers

- ^ a b Kristian Buhl Thomsen (2012), Modernism and Urban Renewal in Denmark 1939–1983 Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine, Aarhus University, 11th Conference on Urban History, EAUH, Prague

- Rigsdagstidende, 1939, pages 1250–1260

- ^ Slum dwellers refuse to vacate railway land Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine, The Dawn, Rawalpindi, Pakistan (August 24, 2013)

- ^ Homeless labourers protest razing of slums Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine The Hindustan Times, Gurgaon, India (April 21, 2013)

- ^ Gardiner, B. (1997), Squatters' Rights and Adverse Possession: A Search for Equitable Application of Property Laws. Ind. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev., 8, 119

- ISBN 3-506-71265-9

- .

- S2CID 142274849.

- ^ a b Strava, Cristiana; Beier, Raffael. The Everyday Life of Urban Inequality: Ethnographic Case Studies of Global Cities. New York: Lexington Books.

- S2CID 153513755.

- ^ Upgrading Urban Communities Archived 2012-11-10 at the Wayback Machine, The World Bank, MIT (2009)

- ^ Ton Van Naerssen, Squatter Access to Land in Metro Manila, Philippine Studies vol. 41, no. 1 (1993); pages 3–20

- .

- ^ TURNER, J. F. C. and FICHTER, R. (Eds) (1972) Freedom to Build. New York: Macmillan[page needed]

- .

- ^ What is Urban Upgrading Archived 2013-05-28 at the Wayback Machine The World Bank Group, MIT (2009)

- ^ S2CID 155052834.

- ISBN 978-9211323931; see pages 7–19

- ^ World Bank Experience with the Provision of Infrastructure Services for the Urban Poor Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine Christine Kessides] The World Bank (1997)

- ^ LUNA, E. M., FERRER, O. P. and IGNACIO, JR., U. (1994) Participatory Action Planning for the Development of Two PSF Projects. Manila: University of Philippines

- ^ BARTONE, C., BERNSTEIN, J., LEITMANN, J. and Eigen, J. (1994) Toward Environmental Strategies for Cities. Washington, DC: World Bank

- ^ BANNERJEE, T. and CHAKROVORTY, S. (1994) Transfer of planning technology and local political economy: a retrospective analysis of Calcutta, Journal of the American Planning Association, 60, pages 71–82

- .

- ^ Smolka, M (2003), Informality, urban poverty, and land market prices. Land Lines 15(1)

- PMID 23440845.

- ^ Urban Land Tenure Policies in Brazil, South Africa, and India: an Assessment of the Issues Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine Donald A. Krueckeberg and Kurt G. Paulsen (2000), Lincoln Institute, Rutgers University

- ^ Marie Huchzermeyer and Aly Karam, Informal settlements: A perpetual challenge? Cape Town, SA: University of Cape Town Press

- ^ Policy and Planning as Public Choice Mass Transit in the United States Archived 2013-05-12 at the Wayback Machine Daniel Lewis and Fred Williams, Federal Transport Agency, DOT, US Government, 1999; Ashgate

- .

- ^ Public transport in Victorian London: Part Two: Underground Archived 2013-05-31 at the Wayback Machine London Transport Museum (2010)

- ^ nycsubway.org—Historic American Engineering Record: Clifton Hood, IRT and New York City, Subway Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Before Public Housing, a City Life Cleared Away Archived 2014-12-16 at the Wayback Machine Sam Roberts, New York Times (May 8, 2005)

- ^ The impact of post-war slum clearance in the UK Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine Becky Tunstall and Stuart Lowe, Social Policy and Social Work, The University of York (November 2012)

- ^ Inter-war Slum Clearance Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine The History of Council Housing; UK

- ^ A New Urban Vision Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine UK's History of Council Housing (2008)

- S2CID 115791262.

- JSTOR 41720411.

- ^ "Urban population living in slums". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ a b Arimah, Ben C. (2010). "The face of urban poverty: Explaining the prevalence of slums in developing countries". World Institute for Development Economics Research. 30. Archived from the original on 2018-10-12. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ^ UN-HABITAT (2006b) (2006). State of the World's Cities 2006/2007: The Millennium Development Goals and Urban Sustainability. London: Earthscan.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "State of the World's Cities Report 2012/2013: Prosperity of Cities" (PDF). UNHABITAT. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ Slum Cities and Cities with Slums" States of the World's Cities 2008/2009. UN-Habitat.

- ^ "State of the World's Cities Report 2012/2013: Prosperity of Cities" (PDF). UNHABITAT. p. 127. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

Further reading

- (2017). Story of the Slum, Chicago West Side 1890-1930

- Parenti, Michael (Jan 2014). What's a Slum?

- The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements. UN-HABITAT. 23 May 2012. ISBN 978-1-1-36554-759. Archived from the originalon 2 June 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013. (original report 2003, revised 2010, reprint 2012)

- Moreno, Eduardo López (2003). Slums of the World: The Face of Urban Poverty in the New Millennium?. UN-HABITAT. ISBN 978-92-1-131683-4. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- Robert Neuwirth: Shadow Cities, New York, 2006, Routledge

- ISBN 1-84467-022-8

- Cavalcanti, Ana Rosa Chagas(2017). Work, Slums, and Informal Settlement Traditions: Architecture of the Favela Do Telegrafo.Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review. 28(2): 71–81.

- Cavalcanti, Ana Rosa Chagas. Housing Shaped by Labour: The Architecture of Scarcity in Informal Settlements. Berlin, 2017, Jovis.

- Elisabeth Blum / Peter Neitzke: FavelaMetropolis. Berichte und Projekte aus Rio de Janeiro und São Paulo, Birkhäuser Basel, Boston, Berlin 2004 ISBN 3-7643-7063-7

- Floris Fabrizio Puppets or people? A sociological analysis of Korogocho slum, Pauline Publication Africa, Nairobi 2007.

- Floris Fabrizio ECCESSI DI CITTÀ: Baraccopoli, campi profughi, città psichedeliche, Paoline, Milano, ISBN 88-315-3318-5

- Matt Birkinshaw A Big Devil in the Jondolos: A report on shack fires by Matt Birkinshaw, 2008

- Every third person will be a slum dweller within 30 years, UN agency warns; John Vidal; The Guardian; October 4, 2003.

- Mute Magazine Vol 2#3, Naked Cities – Struggle in the Global Slums, 2006

- Cities Alliance

- Marx, Benjamin; Stoker, Thomas; Suri, Tavneet (2013). "The Economics of Slums in the Developing World". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 27 (4): 187–210. .