Snow leopard

| Snow leopard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. uncia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Panthera uncia (Schreber, 1775)

| |

| |

| Distribution of the snow leopard, 2017[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

The snow leopard (Panthera uncia), occasionally called ounce, is a

Naming and etymology

The Old French word once, which was intended to be used for the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx), is where the Latin name uncia and the English word ounce both originate. Once is believed to have originated from a previous form of the word lynx through a process known as false splitting. The word once was originally considered to be pronounced as l'once, where l' stands for the elided form of the word la ('the') in French. Once was then understood to be the name of the animal.[2] The word panther derives from the classical Latin panthēra, itself from the ancient Greek πάνθηρ pánthēr, which was used for spotted cats.[3]

Taxonomy and evolution

Felis uncia was the

Uncia uncia was used by Reginald Innes Pocock in 1930 when he reviewed skins and skulls of Panthera species from Asia. He also described morphological differences between snow leopard and leopard skins.[8] Panthera baikalensis-romanii proposed by a Russian scientist in 2000 was a dark brown snow leopard skin from the Petrovsk-Zabaykalsky District in southern Transbaikal.[9]

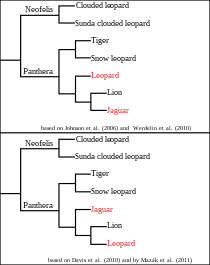

The snow leopard was long classified in the

Until spring 2017, there was no evidence available for the recognition of subspecies. Results of a phylogeographic analysis indicate that three subspecies should be recognised:[15]

- P. u. uncia in the range countries of the Pamir Mountains

- P. u. irbis in Mongolia, and

- P. u. uncioides in the Himalayas and Qinghai.

This view has been both contested and supported by different researchers.[16][17][18][19]

Additionally, an extinct subspecies Panthera uncia pyrenaica was described in 2022 based on material found in France.[20]

Evolution

Based on the phylogenetic analysis of the

The

Characteristics

The snow leopard's fur is whitish to grey with black spots on the head and neck, with larger

The snow leopard shows several adaptations for living in a cold, mountainous environments. Its small rounded ears help to minimize heat loss. Their broad paws well distribute the body weight for walking on snow, and have fur on their undersides to enhance the grip on steep and unstable surfaces; they also help to minimize heat loss. Its long and flexible tail helps to balance the cat in the rocky terrain. The tail is very thick due to fat storage, and is covered in a thick layer of fur, which allows the cat to use it like a blanket to protect its face when asleep.[31][32]

The snow leopard differs from the other Panthera species by a shorter muzzle, an elevated

Distribution and habitat

The snow leopard is distributed from the west of

Potential snow leopard habitat in the Indian Himalayas is estimated at less than 90,000 km2 (35,000 sq mi) in Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, of which about 34,000 km2 (13,000 sq mi) is considered good habitat, and 14.4% is protected. In the beginning of the 1990s, the Indian snow leopard population was estimated at 200–600 individuals living across about 25 protected areas.[36] The Snow Leopard Population Assessment in India (SPAI) Programme counted the number of snow leopards between 2019 and 2023 and found their number to be 718, with 477 in Ladakh, 124 in Uttarakhand, 51 in Himachal Pradesh, 36 in Arunachal Pradesh, 21 in Sikkim, and nine in Jammu and Kashmir.[38]

In summer, the snow leopard usually lives above the

Snow leopards were recorded by camera traps at 16 locations in northeastern Afghanistan's isolated Wakhan Corridor.[39]

Behavior and ecology

The snow leopard's vocalizations include meowing, grunting, prusten and moaning. They can purr when exhaling.[25]

It is

A study in the Gobi Desert from 2008 to 2014 revealed that adult males used a mean home range of 144–270 km2 (56–104 sq mi), while adult females ranged in areas of 83–165 km2 (32–64 sq mi). Their home ranges overlapped less than 20%. These results indicate that about 40% of the 170 protected areas in their range countries are smaller than the home range of a single male snow leopard.[42]

Snow leopards leave

Hunting and diet

The snow leopard is a

The snow leopard actively pursues prey down steep mountainsides, using the momentum of its initial leap to chase animals for up to 300 m (980 ft). Then it drags the prey to a safe location and consumes all edible parts of the carcass. It can survive on a single Himalayan blue sheep for two weeks before hunting again, and one adult individual apparently needs 20–30 adult blue sheep per year.[1][27] Snow leopards have been recorded to hunt successfully in pairs, especially mating pairs.[50]

The snow leopard is easily driven away from livestock and readily abandons kills, often without defending itself.

Reproduction and life cycle

Snow leopards become

The female gives birth in a rocky den or crevice lined with fur shed from her underside. The cubs are born blind and helpless, although already with a thick coat of fur, and weigh 320 to 567 g (11.3 to 20.0 oz). Their eyes open at around seven days, and the cubs can walk at five weeks and are fully weaned by 10 weeks. The cubs leave the den when they are around two to four months of age.[27] Three radio-collared snow leopards in Mongolia's Tost Mountains gave birth between late April and late June. Two female cubs started to part from their mothers at the age of 20 to 21 months, but reunited with them several times for a few days over a period of 4–7 months. One male cub separated from its mother at the age of about 22 months, but stayed in her vicinity for a month and moved out of his natal range at 23 months of age.[53]

The snow leopard has a generation length of eight years.[54]

Threats

Major threats to the population include poaching and illegal trade of its skins and body parts.

Where snow leopards prey on domestic livestock, they are subject to human–wildlife conflict.[1] The loss of natural prey due to overgrazing by livestock, poaching, and defense of livestock are the major drivers for the ever decreasing snow leopard population.[27] Livestock also cause habitat degradation, which, alongside the increasing use of forests for fuel, reduces snow leopard habitat.[60]

Conservation

| Country | Year | Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 2016 | 50–200[61] |

| Bhutan | 2016 | 79–112[62] |

| China | 2016 | 4,500[63] |

| India | 2016 | 516–524[64] |

| Kazakhstan | 2016 | 100–120[65] |

| Kyrgyzstan | 2016 | 300–400[66] |

| Mongolia | 2016 | 1,000[67] |

| Nepal | 2016 | 301–400[68] |

| Pakistan | 2016 | 250-420[69] |

| Russia | 2016 | 70–90[70] |

| Tajikistan | 2016 | 250–280[71] |

| Uzbekistan | 2016 | 30–120[72] |

The snow leopard is listed in

At the end of 2020, 35 cameras were installed on the outskirts of Almaty, Kazakhstan in hopes to catch footage of snow leopards. In November 2021, it was announced by the Russian World Wildlife Fund (WWF) that snow leopards were spotted 65 times on these cameras in the Trans-Ili Alatau mountains since the cameras were installed.[76][42][77][78][79]

Global Snow Leopard Forum

In 2013, government leaders and officials from all 12 countries encompassing the snow leopard's range (Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan) came together at the Global Snow Leopard Forum (GSLF) initiated by the then-President of Kyrgyzstan

In captivity

The Moscow Zoo exhibited the first captive snow leopard in 1872 that had been caught in Turkestan. In Kyrgyzstan, 420 live snow leopards were caught between 1936 and 1988 and exported to zoos around the world. The Bronx Zoo housed a live snow leopard in 1903; this was the first ever specimen exhibited in a North American zoo.[81] The first captive bred snow leopard cubs were born in the 1990s in the Beijing Zoo.[55] The Snow Leopard Species Survival Plan was initiated in 1984; by 1986, American zoos held 234 individuals.[82][83]

Cultural significance

The snow leopard is widely used in

See also

References

- ^ . Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- S2CID 251028590.

- ^ Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (1940). "πάνθηρ". A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2021-02-21.

- ISBN 978-0-12-802496-6.

- ^ Gray, J. E. (1854). "The ounces". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 2. 14: 394.

- ^ Ehrenberg, C. G. (1830). "Observations et données nouvelles sur le tigre du nord et la panthère du nord, recueillies dans le voyage de Sibérie fait par M.A. de Humboldt, en l'année 1829". Annales des sciences naturelles, Zoologie. 21: 387–412.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-226-51823-7.

- ^ Medvedev, D. G. (2000). "Morfologicheskie otlichiya irbisa iz Yuzhnogo Zabaikalia" [Morphological differences of the snow leopard from Southern Transbaikalia]. Vestnik Irkutskoi Gosudarstvennoi Sel'skokhozyaistvennoi Akademyi [Proceedings of Irkutsk State Agricultural Academy]. 20: 20–30.

- OCLC 62265494.

- ^ from the original on 2020-10-04. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- ^ ]

- ISBN 9780128024966. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 69. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-17. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- PMID 28498961.

- PMID 29225352.

- PMID 29434338.

- from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- S2CID 233480791. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2021-05-19. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- S2CID 246433218.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-923445-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2018-09-25. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- PMID 22016768.

- PMID 24225466.

- PMID 26518481.

- ^ JSTOR 3503882. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2012-04-01.

- ^ ISBN 9782831700458.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-226-77999-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- .

- .

- PMID 26246610.

- ^ Chadwick, D. H. (2008). "Out of the Shadows". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2009-07-11. Retrieved 2010-01-29.

- ISBN 978-1-56660-746-9.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1930). "The panthers and ounces of Asia. Part II. The panthers of Kashmir, India, and Ceylon". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 34 (2): 307–336.

- PMID 2606766.

- PMID 12363272.

- ^ a b McCarthy, T. M. & Chapron, G. (2003). Snow Leopard Survival Strategy (PDF). Seattle, USA: International Snow Leopard Trust and Snow Leopard Network. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-11. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- S2CID 20787622.

- ^ "Snow leopard census: Ladakh leads the pack with 477, J&K records minimum at 9 of total 718". Greaterkashmir. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- S2CID 96170915.

- ^ Jackson, R. & Ahlborn, G. (1988). "Observations on the ecology of snow leopard in west Nepal" (PDF). In Freeman, H. (ed.). Proceedings of the Fifth International Snow Leopard Symposium. India: International Snow Leopard Trust. pp. 65–97. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-12. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ^ Jackson, R. (1996). Home Range, Movements and Habitat Use of Snow Leopard in Nepal (PhD). London: University of London.

- ^ doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.08.034. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2021-05-19. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- S2CID 200084900.

- doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2015.02.003. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2016-01-28. Retrieved 2015-03-25.

- S2CID 30967502.

- PMID 24533080.

- ^ PMID 22393381.

- .

- S2CID 266289402. Archived from the original(PDF) on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- .

- ^ a b Heptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Snow Leopard, Ounce [Irbis]". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 276–319.

- ISBN 9780128022139.

- S2CID 225114786.

- ^ Pacifici, M.; Santini, L.; Di Marco, M.; Baisero, D.; Francucci, L.; Grottolo Marasini, G.; Visconti, P. & Rondinini, C. (2013). "Generation length for mammals". Nature Conservation (5): 87–94. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2021-12-14.

- ^ CiteSeerX 10.1.1.498.7184.

- ^ ISBN 1-85850-201-2. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2021-04-20. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ISBN 978-1-85850-409-4. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2021-04-10. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ^ a b Maheshwari, A.; Niraj, S. K.; Sathyakumar, S.; Thakur, M. & Sharma, L. K. (2016). "Snow leopard illegal trade in Afghanistan: A rapid survey". Cat News (64): 22–23.

- doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.03.001. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ "What water means to snow leopards". UNDP. 2 June 2022. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ a b Lham, D.; Thinley, P.; Wangchuk, S.; Wangchuk, N.; Lham, K.; Namgay, T.; Tharchen, L. & Wangchuck, T. (2016). National Snow Leopard Survey of Bhutan – Phase II: Camera Trap Survey for Population Estimation (Report). Thimphu, Bhutan: Wildlife Conservation Division, Department of Forests and Park Services.

- ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ ISBN 9780128024966.

- ISBN 9780128024966.

- ISBN 9780128024966.

- ISBN 9780128024966.

- ISBN 9780128024966.

- ISBN 9780128024966.

- ISBN 9780128024966. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ISBN 9780128024966.

- ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ Kattel, B. & Bajiimaya, S. (1995). "Status and conservation of Snow Leopard in Nepal". In Jackson, R. & Ahmad, A. A. (eds.). Proceedings of the Eighth International Snow Leopard Symposium, 12–16 November 1995, Islamabad, Pakistan. Islamabad, Pakistan: International Snow Leopard Trust. pp. 21–27.

- ^ Paltsyn, M.Y.; Spitsyn, S.V.; Kuksin, A.N. & Istomov, S.V. (2012). Snow Leopard Conservation in Russia – Data for Conservation Strategy for Snow Leopard in Russia (Report). Krasnoyarsk: WWF Russia.

- ^ Riordan, P. & Kun, S. (2010). "The Snow Leopard in China". Cat News (Special Issue 5): 14–17.

- ^ Bulatkulova, Saniya (2021-11-21). "Snow Leopards Caught On Camera 65 Times and Counting This Year Alone in Almaty Region". The Astana Times. Archived from the original on 2021-11-23. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ISBN 9780128024966. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ Jackson, R. (1998). "People-Wildlife Conflict Management in the Qomolangma Nature Preserve, Tibet" (PDF). In Wu Ning; D. Miller; Lhu Zhu; J. Springer (eds.). Tibet's Biodiversity: Conservation and Management. Proceedings of a Conference, August 30 – September 4, 1998. Tibet Forestry Department and World Wide Fund for Nature. pp. 40–46. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ISBN 9780128024966. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ "Global Snow Leopard Conservation Forum". World Bank. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- ^ Wharton, D. & Freeman, H. (1988). "The Snow Leopard in North America: Captive Breeding Under the Species Survival Plan". In Freeman, H. (ed.). Proceedings of the Fifth International Snow Leopard Symposium. Seattle and Dehra Dun: International Snow Leopard Trust and Wildlife Institute of India. pp. 131–136.

- ISBN 978-0-12-802213-9, retrieved 2023-05-15

- ISBN 978-0-295-74658-6.

- ^ Cambridge, University of. "Understanding local attitudes to snow leopards vital for their ongoing protection". phys.org. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- ISBN 978-0-12-802213-9, retrieved 2023-05-14

- ISSN 2160-617X.

- ^ Cambridge, University of. "Understanding local attitudes to snow leopards vital for their ongoing protection". phys.org. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

Further reading

- Jackson, R.; Hillard, D. (June 1986). "Tracking the Elusive Snow Leopard". OCLC 643483454.

- Janczewski, D. N.; Modi, W. S.; Stephens, J. C.; O'Brien, S. J. (July 1995). "Molecular Evolution of Mitochondrial 12S RNA and Cytochrome b Sequences in the Pantherine Lineage of Felidae". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 12 (4): 690–707. PMID 7544865.

External links

- "The Snow Leopard Network". Snow Leopard Network.

- "Ensuring Snow Leopard survival and conserving mountain landscapes by expanding environmental awareness and sharing innovative practices through community stewardship and partnerships". Snow Leopard Conservancy.

- "Snow Leopard Program". Panthera. Archived from the original on 2015-10-07. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- "Snow Leopard". IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.