Socialism

This article may be readable prose size was 19,000 words. . (November 2023) |

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Party politics |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Economic systems |

|---|

|

Major types

|

|

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems[1] characterised by social ownership of the means of production,[2] as opposed to private ownership.[3][4][5] It describes the economic, political, and social theories and movements associated with the implementation of such systems.[6] Social ownership can take various forms, including public, community, collective, cooperative,[7][8][9] or employee.[10][11] Traditionally, socialism is on the left wing of the political spectrum.[12] Types of socialism vary based on the role of markets and planning in resource allocation, and the structure of management in organizations.[13][14]

Socialist systems divide into

The socialist

While the emergence of the

Etymology

For Andrew Vincent, "[t]he word 'socialism' finds its root in the Latin sociare, which means to combine or to share. The related, more technical term in Roman and then medieval law was societas. This latter word could mean companionship and fellowship as well as the more legalistic idea of a consensual contract between freemen".[43]

Initial use of socialism was claimed by

The definition and usage of socialism settled by the 1860s, replacing

In

History

Early socialism

Socialist models and ideas espousing common or public ownership have existed since antiquity. The economy of the 3rd century BCE

The first self-conscious socialist movements developed in the 1820s and 1830s. Groups such as the

The Chartists gathered significant numbers around the

The first advocates of socialism favoured social levelling in order to create a

West European social critics, including

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune was a government that ruled Paris from 18 March (formally, from 28 March) to 28 May 1871. The Commune was the result of an uprising in Paris after France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War. The Commune elections were held on 26 March. They elected a Commune council of 92 members, one member for each 20,000 residents.[88]

Because the Commune was able to meet on fewer than 60 days in total, only a few decrees were actually implemented. These included the separation of church and state; the remission of rents owed for the period of the siege (during which payment had been suspended); the abolition of night work in the hundreds of Paris bakeries; the granting of pensions to the unmarried companions and children of National Guards killed on active service; and the free return of all workmen's tools and household items valued up to 20 francs that had been pledged during the siege.[89]

First International

In 1864, the First International was founded in London. It united diverse revolutionary currents, including socialists such as the French followers of Proudhon,

Bakunin's followers were called

The

Guild socialism is a political movement advocating workers' control of industry through the medium of trade-related guilds "in an implied contractual relationship with the public".[101] It originated in the United Kingdom and was at its most influential in the first quarter of the 20th century. Inspired by medieval guilds, theorists such as Samuel George Hobson and G. D. H. Cole advocated the public ownership of industries and their workforces' organisation into guilds, each of which under the democratic control of its trade union. Guild socialists were less inclined than Fabians to invest power in a state.[95] At some point, like the American Knights of Labor, guild socialism wanted to abolish the wage system.[102]

Second International

As the ideas of Marx and Engels gained acceptance, particularly in central Europe, socialists sought to unite in an international organisation. In 1889 (the centennial of the French Revolution), the Second International was founded, with 384 delegates from twenty countries representing about 300 labour and socialist organisations.

Reformism arose as an alternative to revolution.

In South America, the

Early 20th century

For four months in 1904, Australian Labor Party leader Chris Watson was the Prime Minister of the country. Watson thus became the head of the world's first socialist or social democratic parliamentary government.[107] Australian historian Geoffrey Blainey argues that the Labor Party was not socialist at all in the 1890s, and that socialist and collectivist elements only made their way in the party's platform in the early 20th century.[108]

In 1909, the first Kibbutz was established in Palestine[109] by Russian Jewish immigrants. The Kibbutz Movement expanded through the 20th century following a doctrine of Zionist socialism.[110] The British Labour Party first won seats in the House of Commons in 1902.

By 1917, the patriotism of

Russian Revolution

In February 1917, a revolution occurred in Russia. Workers, soldiers and peasants established

Lenin had published

Upon arriving in

The day after assuming executive power on 25 January, Lenin wrote Draft Regulations on Workers' Control, which granted workers control of businesses with more than five workers and office employees and access to all books, documents and stocks and whose decisions were to be "binding upon the owners of the enterprises".

The Constituent Assembly elected SR leader

In the interwar period, Soviet Union experienced two major famines.[undue weight? ] The First famine occurred in 1921–1922 with death estimates varying between 1 and 10 million dead. It was caused by a combination of factors – severe drought and failed harvests, continuous war since 1914, forced collectivisation of farms and requisition of grain and seed from peasants (preventing the sowing of crops) by the Soviet authorities, and an economic blockade of the Soviet Union by the Allies. The experience with the famine led Lenin to replace war communism with the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921 to alleviate the extreme shortages.[125] Under the NEP, private ownership was allowed for small and medium-sized enterprises. While large industry remained state controlled.

A second major famine occurred in

The Soviet economy was the modern world's first

Third International and the revolutionary wave

The Bolshevik Russian Revolution of January 1918 launched Communist parties in many countries and a wave of revolutions until the mid-1920s. Few communists doubted that the Russian experience depended on successful, working-class socialist revolutions in developed capitalist countries.[127][128] In 1919, Lenin and Leon Trotsky organised the world's Communist parties into an international association of workers—the Communist International (Comintern), also called the Third International.

The Russian Revolution influenced uprisings in other countries. The German Revolution of 1918–1919 replaced Germany's imperial government with a republic. The revolution lasted from November 1918 until the establishment of the Weimar Republic in August 1919. It included an episode known as the Bavarian Soviet Republic[129][130][131][132] and the Spartacist uprising. A short lived Hungarian Soviet Republic was set up in Hungary March 21 to August 1, 1919. It was led by Béla Kun.[133][134][135][page needed] It instituted a Red Terror.[136][page needed] After the regime was put down, an even more brutal White Terror followed. Kun managed to escape to the Soviet Union, where he co-led murder of tens of thousands of White Russians.[137][138] He was killed in the 1930 Soviet purges.[139][140]

In Italy, the events known as the

There was a short-lived

4th World Congress of the Communist International

In 1922, the fourth congress of the Communist International took up the policy of the united front. It urged communists to work with rank-and-file social democrats while remaining critical of their leaders. They criticised those leaders for betraying the working class by supporting the capitalists' war efforts. The social democrats pointed to the dislocation caused by revolution and later the growing authoritarianism of the communist parties. The Labour Party rejected the Communist Party of Great Britain's application to affiliate to them in 1920.

On seeing the Soviet State's growing coercive power in 1923, a dying Lenin said Russia had reverted to "a bourgeois tsarist machine ... barely varnished with socialism".[145] After Lenin's death in January 1924, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union—then increasingly under the control of Joseph Stalin—rejected the theory that socialism could not be built solely in the Soviet Union in favour of the concept of socialism in one country. Stalin developed a bureaucratic and totalitarian government, which was condemned by democratic socialists and anarchists for undermining the Revolution's ideals.[146][147]

The Russian Revolution and its aftermath motivated national Communist parties elsewhere that gained political and social influence, such as those in

Left-wing groups which did not agree to the centralisation and abandonment of the soviets by the Bolshevik Party (see

The Second International and the Two-and-a-Half International

The International Socialist Commission (ISC, also known as Berne International) was formed in February 1919 at a meeting in Bern by parties that wanted to resurrect the Second International.[156] Centrist socialist parties which did not want to be a part of the resurrected Second International (ISC) or Comintern formed the International Working Union of Socialist Parties (IWUSP, also known as Vienna International, Vienna Union, or Two-and-a-Half International) on 27 February 1921 at a conference in Vienna.[157] The ISC and the IWUSP joined to form the Labour and Socialist International (LSI) in May 1923 at a meeting in Hamburg.[158]

From the Great Depression to the World War

The 1920s and 1930s were marked by an increasing divergence between democratic and reformists socialists (mainly affiliated with the Labour and Socialist International) and revolutionary socialists (mainly affiliated with the Communist International), but also by tension within the Communist movement between the dominant Stalinists and dissidents such as Trotsky's followers in the Left Opposition. Trotsky's Fourth International was established in France in 1938 when Trotskyists argued that the Comintern or Third International had become irretrievably "lost to Stalinism" and thus incapable of leading the working class to power.[159]

Spanish Civil War

In the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), socialists (including the democratic socialist

The

Mid-20th century

Post-World War II

The rise of Nazism and the start of World War II led to the dissolution of the LSI in 1940. After the War, the Socialist International was formed in Frankfurt in July 1951 as its successor.[165]

After World War II, social democratic governments introduced social reform and

In 1945, the

Nordic countries

During most of the post-war era, Sweden was governed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party largely in cooperation with trade unions and industry.[173] The party held power from 1936 to 1976, 1982 to 1991, 1994 to 2006 and 2014 to 2022, most often in minority governments. Party leader Tage Erlander led the government from 1946 to 1969, the longest uninterrupted parliamentary government. These governments substantially expanded the welfare state.[174] Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme identified as a "democratic socialist"[175] and was described as a "revolutionary reformist".[176]

The Norwegian Labour Party was established in 1887 and was largely a trade union federation. The party did not proclaim a socialist agenda, elevating universal suffrage and dissolution of the union with Sweden as its top priorities. In 1899, the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions separated from the Labour Party. Around the time of the Russian Revolution, the Labour Party moved to the left and joined the Communist International from 1919 through 1923. Thereafter, the party still regarded itself as revolutionary, but the party's left-wing broke away and established the Communist Party of Norway while the Labour Party gradually adopted a reformist line around 1930. In 1935, Johan Nygaardsvold established a coalition that lasted until 1945.[177]

From 1946 to 1962, the Norwegian Labour Party held an absolute majority in the parliament led by

In countries such as Sweden, the Rehn–Meidner model[182] allowed capitalists owning productive and efficient firms to retain profits at the expense of the firms' workers, exacerbating inequality and causing workers to agitate for a share of the profits in the 1970s. At that time, women working in the state sector began to demand better wages. Rudolf Meidner established a study committee that came up with a 1976 proposal to transfer excess profits into worker-controlled investment funds, with the intention that firms would create jobs and pay higher wages rather than reward company owners and managers.[86] Capitalists immediately labeled this proposal as socialism and launched an unprecedented opposition—including calling off the class compromise established in the 1938 Saltsjöbaden Agreement.[183] Social democratic parties are some of the oldest such parties and operate in all Nordic countries. Countries or political systems that have long been dominated by social democratic parties are often labelled social democratic.[184][185] Those countries fit the social democratic type of "high socialism" which is described as favouring "a high level of decommodification and a low degree of stratification".[186]

The Nordic model is a form of economic-political system common to the

In Norway, the first mandatory social insurances were introduced by conservative cabinets in 1895 (Francis Hagerups's cabinet) and 1911 (Konow's Cabinet). During the 1930s, the Labour Party adopted the conservatives' welfare state project. After World War II, all political parties agreed that the welfare state should be expanded. Universal social security (Folketrygden) was introduced by the conservative Borten's Cabinet.[194][195] Norway's economy is open to the international or European market for most products and services, joining the European Union's internal market in 1994 through European Economic Area. Some of the mixed economy institutions from the post-war period were relaxed by the conservative cabinet of the 1980s and the finance market was deregulated.[196] Within the Varieties of Capitalism-framework, Finland, Norway and Sweden are identified as coordinated market economies.[197]

Soviet Union and Eastern Europe

The Soviet era saw competition between the Soviet-led Eastern Bloc and the United States-led Western Bloc. The Soviet system was seen as a rival of and a threat to Western capitalism for most of the 20th century.[198][page needed]

The Eastern Bloc was the group of

The

Asia, Africa, and Latin America

In the post-war years, socialism became increasingly influential in many then-developing countries. Embracing Third World socialism, countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America often nationalised industries. During India's freedom movement and fight for independence, many figures in the left-wing faction of the Indian National Congress organised themselves as the Congress Socialist Party. Their politics and those of the early and intermediate periods of Jayaprakash Narayan's career combined a commitment to the socialist transformation of society with a principled opposition to the one-party authoritarianism they perceived in the Stalinist model.[207]

The Chinese Communist Revolution was the second stage in the Chinese Civil War, which ended with the establishment of the People's Republic of China led by the Chinese Communist Party. The then-Chinese Kuomintang Party in the 1920s incorporated Chinese socialism as part of its ideology.[208][209] Between 1958 and 1962 during the Great Leap Forward in the People's Republic of China, some 30 million people starved to death[210] and at least 45 million died overall.[211]

The emergence of this new political entity in the frame of the

The Cuban Revolution (1953–1959) was an armed revolt conducted by Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement and its allies against the government of Fulgencio Batista. Castro's government eventually adopted socialism and the communist ideology, becoming the Communist Party of Cuba in October 1965.[214][215][216]

In Indonesia in the mid-1960s, a coup attempt blamed on the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) was countered by an anti-communist purge led by Suharto, which mainly targeted the growing influence of the PKI and other leftist groups, with significant support from the United States, which culminated in the overthrow of Sukarno.[217] These events resulted not only in the total destruction of the PKI but also the political left in Indonesia, and paved the way for a major shift in the balance of power in Southeast Asia towards the West, a significant turning point in the global Cold War.[218][219][220]

New Left

The New Left was a term used mainly in the United Kingdom and United States in reference to

In the United States, the New Left was associated with the

Protests of 1968

The protests of 1968 represented a worldwide escalation of social conflicts, predominantly characterised by popular rebellions against military, capitalist and bureaucratic elites who responded with an escalation of

Mass socialist movements grew not only in the United States, but also in most European countries. In many other capitalist countries, struggles against dictatorships, state repression and colonisation were also marked by protests in 1968, such as the Tlatelolco massacre in Mexico City and the escalation of guerrilla warfare against the military dictatorship in Brazil.

Countries governed by Communist parties saw protests against bureaucratic and military elites too. In Eastern Europe, widespread protests escalated particularly in the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia. In response, Soviet Union occupied Czechoslovakia. The occupation was denounced by the Italian and French[229] Communist parties and the Communist Party of Finland, but defended by the Portuguese Communist Party secretary-general Álvaro Cunhal[230] the Communist Party of Luxembourg[229] and conservative factions of the Communist Party of Greece.[229]

In the

Late 20th century

This section may be readable prose size was 2,000 words. . (March 2024) |

In the 1960s, a socialist tendency within the Latin American Catholic church appeared and was known as

The Nicaraguan Revolution encompassed the rising opposition to the

In 1976, the word socialist was added to the Preamble of the

In 1982, the newly elected French socialist government of François Mitterrand nationalised parts of a few key industries, including banks and insurance companies.[243] Eurocommunism was a trend in the 1970s and 1980s in various Western European Communist parties to develop a theory and practice of social transformation that was more relevant for a Western European country and less aligned to the influence or control of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Outside Western Europe, it is sometimes called neocommunism.[244]

Some Communist parties with strong popular support, notably the

Until its 1976 Geneva Congress, the Socialist International (SI) had few members outside Europe and no formal involvement with Latin America.

After

The Soviet Union experienced continued increases in mortality rate (particularly among men) as far back as 1965.

A lasting legacy of Communism in Soviet Union remains in the physical infrastructure created during decades of combined industrial production practices, and widespread environmental destruction.[261] The transition to capitalist market economies in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc was accompanied by Washington Consensus-inspired "shock therapy",[262] advocated by Western institutions and economists with the intent to replace state socialism with capitalism and integrate these countries into the capitalist western world.[263]

Following a transition to free-market capitalism, there was initially a steep fall in the standard of living. Post-Communist Russia experienced rising

The average post-Communist country had returned to 1989 levels of per-capita GDP by 2005,[275] and as of 2015, some countries were still behind that.[276] Several scholars state that the negative economic developments in post-Communist countries after the fall of Communism led to increased nationalist sentiment and nostalgia for the Communist era.[277][278][279] In 2011, The Guardian published an analysis of the former Soviet countries twenty years after the fall of the USSR. They found that "GDP fell as much as 50 percent in the 1990s in some republics... as capital flight, industrial collapse, hyperinflation and tax avoidance took their toll," but that there was a rebound in the 2000s, and by 2010 "some economies were five times as big as they were in 1991." Life expectancy has grown since 1991 in some of the countries, but fallen in others; likewise, some held free and fair elections, while others remained authoritarian.[280] By 2019, the majority of people in most Eastern European countries approved of the shift to multiparty democracy and a market economy, with approval being highest among residents of Poland and residents in the territory of what was once East Germany, and disapproval being the highest among residents of Russia and Ukraine. In addition, 61 per cent said that standards of living were now higher than they had been under Communism, while only 31 per cent said that they were worse, with the remaining 8 per cent saying that they did not know or that standards of living had not changed.[281]

Many social democratic parties, particularly after the Cold War, adopted neoliberal market policies including

In the 1990s, the British Labour Party under Tony Blair enacted policies based on the free-market economy to deliver public services via the private finance initiative. Influential in these policies was the idea of a Third Way between Old Left state socialism and New Right market capitalism, and a re-evaluation of welfare state policies.[285][286][287] In 1995, the Labour Party re-defined its stance on socialism by re-wording Clause IV of its constitution, defining socialism in ethical terms and removing all references to public, direct worker or municipal ownership of the means of production. The Labour Party stated: "The Labour Party is a democratic socialist party. It believes that, by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone, so as to create, for each of us, the means to realise our true potential, and, for all of us, a community in which power, wealth, and opportunity are in the hands of the many, not the few."[288] Left-wing critics of the Third Way argued that it reduced equality to an equal opportunity to compete in an economy in which the rich were growing richer and the poor were becoming more disadvantaged, which the leftists argue is not socialist.[40]

Starting in the late 20th century, the development of a

Early 21st century

In 1990, the

Many mainstream democratic socialist and social democratic parties continued to drift right-wards. On the right of the socialist movement, the

In Europe, the share of votes for such socialist parties was at its 70-year lowest in 2015. For example, the

Social and political theory

Early socialist thought took influences from a diverse range of philosophies such as civic

The fundamental objective of socialism is to attain an advanced level of material production and therefore greater productivity, efficiency and rationality as compared to capitalism and all previous systems, under the view that an expansion of human productive capability is the basis for the extension of freedom and equality in society.[302] Many forms of socialist theory hold that human behaviour is largely shaped by the social environment. In particular, socialism holds that social mores, values, cultural traits and economic practices are social creations and not the result of an immutable natural law.[303][304] The object of their critique is thus not human avarice or human consciousness, but the material conditions and man-made social systems (i.e. the economic structure of society) which give rise to observed social problems and inefficiencies. Bertrand Russell, often considered to be the father of analytic philosophy, identified as a socialist. Russell opposed the class struggle aspects of Marxism, viewing socialism solely as an adjustment of economic relations to accommodate modern machine production to benefit all of humanity through the progressive reduction of necessary work time.[305]

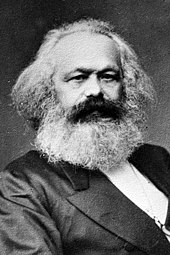

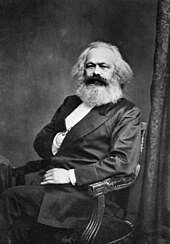

Socialists view creativity as an essential aspect of human nature and define freedom as a state of being where individuals are able to express their creativity unhindered by constraints of both material scarcity and coercive social institutions.[306] The socialist concept of individuality is intertwined with the concept of individual creative expression. Karl Marx believed that expansion of the productive forces and technology was the basis for the expansion of human freedom and that socialism, being a system that is consistent with modern developments in technology, would enable the flourishing of "free individualities" through the progressive reduction of necessary labour time. The reduction of necessary labour time to a minimum would grant individuals the opportunity to pursue the development of their true individuality and creativity.[307]

Criticism of capitalism

Socialists argue that the accumulation of capital generates waste through externalities that require costly corrective regulatory measures. They also point out that this process generates wasteful industries and practices that exist only to generate sufficient demand for products such as high-pressure advertisement to be sold at a profit, thereby creating rather than satisfying economic demand.

Socialists view

Excessive disparities in income distribution lead to social instability and require costly corrective measures in the form of redistributive taxation, which incurs heavy administrative costs while weakening the incentive to work, inviting dishonesty and increasing the likelihood of tax evasion while (the corrective measures) reduce the overall efficiency of the market economy.

Marxism

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or—this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms—with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure.[319]

—Karl Marx,

Marx and Engels held the view that the consciousness of those who earn a wage or salary (the working class in the broadest Marxist sense) would be moulded by their conditions of

Marx and Engels used the terms socialism and communism interchangeably, but many later Marxists defined socialism as a specific historical phase that would displace capitalism and precede communism.[52][55]

The major characteristics of socialism (particularly as conceived by Marx and Engels after the Paris Commune of 1871) are that the proletariat would control the means of production through a workers' state erected by the workers in their interests.

For

Role of the state

Socialists have taken different perspectives on the state and the role it should play in revolutionary struggles, in constructing socialism and within an established socialist economy.

In the 19th century, the philosophy of state socialism was first explicitly expounded by the German political philosopher Ferdinand Lassalle. In contrast to Karl Marx's perspective of the state, Lassalle rejected the concept of the state as a class-based power structure whose main function was to preserve existing class structures. Lassalle also rejected the Marxist view that the state was destined to "wither away". Lassalle considered the state to be an entity independent of class allegiances and an instrument of justice that would therefore be essential for achieving socialism.[323]

Preceding the Bolshevik-led revolution in Russia, many socialists including

Joseph Schumpeter rejected the association of socialism and social ownership with state ownership over the means of production because the state as it exists in its current form is a product of capitalist society and cannot be transplanted to a different institutional framework. Schumpeter argued that there would be different institutions within socialism than those that exist within modern capitalism, just as feudalism had its own distinct and unique institutional forms. The state, along with concepts like property and taxation, were concepts exclusive to commercial society (capitalism) and attempting to place them within the context of a future socialist society would amount to a distortion of these concepts by using them out of context.[325]

Utopian versus scientific

Utopian socialism is a term used to define the first currents of modern socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier and Robert Owen which inspired Karl Marx and other early socialists.[326] Visions of imaginary ideal societies, which competed with revolutionary social democratic movements, were viewed as not being grounded in the material conditions of society and as reactionary.[327] Although it is technically possible for any set of ideas or any person living at any time in history to be a utopian socialist, the term is most often applied to those socialists who lived in the first quarter of the 19th century who were ascribed the label "utopian" by later socialists as a negative term to imply naivete and dismiss their ideas as fanciful or unrealistic.[86]

Religious sects whose members live communally such as the

Reform versus revolution

Revolutionary socialists believe that a social revolution is necessary to effect structural changes to the socioeconomic structure of society. Among revolutionary socialists there are differences in strategy, theory and the definition of revolution. Orthodox Marxists and left communists take an

Reformism is generally associated with

The debate on the ability for social democratic reformism to lead to a socialist transformation of society is over a century old. Reformism is criticized for being paradoxical as it seeks to overcome the existing economic system of capitalism while trying to improve the conditions of capitalism, thereby making it appear more tolerable to society. According to

Economics

The economic anarchy of capitalist society as it exists today is, in my opinion, the real source of the evil. ... I am convinced there is only one way to eliminate these grave evils, namely through the establishment of a socialist economy, accompanied by an educational system which would be oriented toward social goals. In such an economy, the means of production are owned by society itself and are utilised in a planned fashion. A planned economy, which adjusts production to the needs of the community, would distribute the work to be done among all those able to work and would guarantee a livelihood to every man, woman, and child. The education of the individual, in addition to promoting his own innate abilities, would attempt to develop in him a sense of responsibility for his fellow men in place of the glorification of power and success in our present society.[334]

—Albert Einstein, "Why Socialism?", 1949

Socialist economics starts from the premise that "individuals do not live or work in isolation but live in cooperation with one another. Furthermore, everything that people produce is in some sense a social product, and everyone who contributes to the production of a good is entitled to a share in it. Society as whole, therefore, should own or at least control property for the benefit of all its members".[95]

The original conception of socialism was an economic system whereby production was organised in a way to directly produce goods and services for their utility (or use-value in classical and Marxian economics), with the direct allocation of resources in terms of physical units as opposed to financial calculation and the economic laws of capitalism (see law of value), often entailing the end of capitalistic economic categories such as rent, interest, profit and money.[335] In a fully developed socialist economy, production and balancing factor inputs with outputs becomes a technical process to be undertaken by engineers.[336]

The ownership of the

Management and control over the activities of enterprises are based on self-management and self-governance, with equal power-relations in the workplace to maximise occupational autonomy. A socialist form of organisation would eliminate controlling hierarchies so that only a hierarchy based on technical knowledge in the workplace remains. Every member would have decision-making power in the firm and would be able to participate in establishing its overall policy objectives. The policies/goals would be carried out by the technical specialists that form the coordinating hierarchy of the firm, who would establish plans or directives for the work community to accomplish these goals:[345][346]

The role and use of money in a hypothetical socialist economy is a contested issue. Nineteenth century socialists including Karl Marx, Robert Owen, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and John Stuart Mill advocated various forms of labour vouchers or labour credits, which like money would be used to acquire articles of consumption, but unlike money they are unable to become capital and would not be used to allocate resources within the production process. Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Trotsky argued that money could not be arbitrarily abolished following a socialist revolution. Money had to exhaust its "historic mission", meaning it would have to be used until its function became redundant, eventually being transformed into bookkeeping receipts for statisticians and only in the more distant future would money not be required for even that role.[347]

Planned economy

A planned economy is a type of economy consisting of a mixture of public ownership of the means of production and the coordination of production and distribution through economic planning. A planned economy can be either decentralised or centralised. Enrico Barone provided a comprehensive theoretical framework for a planned socialist economy. In his model, assuming perfect computation techniques, simultaneous equations relating inputs and outputs to ratios of equivalence would provide appropriate valuations to balance supply and demand.[348]

The most prominent example of a planned economy was the

Although central planning was largely supported by

Self-managed economy

Socialism, you see, is a bird with two wings. The definition is 'social ownership and democratic control of the instruments and means of production.'[353]

A self-managed, decentralised economy is based on autonomous self-regulating economic units and a decentralised mechanism of resource allocation and decision-making. This model has found support in notable classical and neoclassical economists including

One such system is the cooperative economy, a largely free market economy in which workers manage the firms and democratically determine remuneration levels and labour divisions. Productive resources would be legally owned by the cooperative and rented to the workers, who would enjoy usufruct rights.[356] Another form of decentralised planning is the use of cybernetics, or the use of computers to manage the allocation of economic inputs. The socialist-run government of Salvador Allende in Chile experimented with Project Cybersyn, a real-time information bridge between the government, state enterprises and consumers.[357] Another, more recent variant is participatory economics, wherein the economy is planned by decentralised councils of workers and consumers. Workers would be remunerated solely according to effort and sacrifice, so that those engaged in dangerous, uncomfortable and strenuous work would receive the highest incomes and could thereby work less.[358] A contemporary model for a self-managed, non-market socialism is Pat Devine's model of negotiated coordination. Negotiated coordination is based upon social ownership by those affected by the use of the assets involved, with decisions made by those at the most localised level of production.[359]

Michel Bauwens identifies the emergence of the open software movement and peer-to-peer production as a new alternative mode of production to the capitalist economy and centrally planned economy that is based on collaborative self-management, common ownership of resources and the production of use-values through the free cooperation of producers who have access to distributed capital.[360]

The economy of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia established a system based on market-based allocation, social ownership of the means of production and self-management within firms. This system substituted Yugoslavia's Soviet-type central planning with a decentralised, self-managed system after reforms in 1953.[364]

The Marxian economist Richard D. Wolff argues that "re-organising production so that workers become collectively self-directed at their work-sites" not only moves society beyond both capitalism and state socialism of the last century, but would also mark another milestone in human history, similar to earlier transitions out of slavery and feudalism.[365] As an example, Wolff claims that Mondragon is "a stunningly successful alternative to the capitalist organisation of production".[366]

State-directed economy

State socialism can be used to classify any variety of socialist philosophies that advocates the ownership of the means of production by the state apparatus, either as a transitional stage between capitalism and socialism, or as an end-goal in itself. Typically, it refers to a form of technocratic management, whereby technical specialists administer or manage economic enterprises on behalf of society and the public interest instead of workers' councils or workplace democracy.

A state-directed economy may refer to a type of mixed economy consisting of public ownership over large industries, as promoted by various Social democratic political parties during the 20th century. This ideology influenced the policies of the British Labour Party during Clement Attlee's administration. In the biography of the 1945 United Kingdom Labour Party Prime Minister Clement Attlee, Francis Beckett states: "[T]he government ... wanted what would become known as a mixed economy."[367]

Nationalisation in the United Kingdom was achieved through compulsory purchase of the industry (i.e. with compensation). British Aerospace was a combination of major aircraft companies British Aircraft Corporation, Hawker Siddeley and others. British Shipbuilders was a combination of the major shipbuilding companies including Cammell Laird, Govan Shipbuilders, Swan Hunter and Yarrow Shipbuilders, whereas the nationalisation of the coal mines in 1947 created a coal board charged with running the coal industry commercially so as to be able to meet the interest payable on the bonds which the former mine owners' shares had been converted into.[368][369]

Market socialism

Market socialism consists of publicly owned or cooperatively owned enterprises operating in a

The current economic system in China is formally referred to as a

Politics

While major socialist political movements include anarchism, communism, the labour movement, Marxism, social democracy, and syndicalism, independent socialist theorists,

In his Dictionary of Socialism (1924), Angelo S. Rappoport analysed forty definitions of socialism to conclude that common elements of socialism include general criticism of the social effects of

In The Concepts of Socialism (1975), Bhikhu Parekh identifies four core principles of socialism and particularly socialist society, namely sociality, social responsibility, cooperation and planning.[388] In his study Ideologies and Political Theory (1996), Michael Freeden states that all socialists share five themes: the first is that socialism posits that society is more than a mere collection of individuals; second, that it considers human welfare a desirable objective; third, that it considers humans by nature to be active and productive; fourth, it holds the belief of human equality; and fifth, that history is progressive and will create positive change on the condition that humans work to achieve such change.[388]

Anarchism

Anarchism advocates

The authoritarian–

According to anarchists such as the authors of An Anarchist FAQ, anarchism is one of the many traditions of socialism. For anarchists and other anti-authoritarian socialists, socialism "can only mean a classless and anti-authoritarian (i.e. libertarian) society in which people manage their own affairs, either as individuals or as part of a group (depending on the situation). In other words, it implies self-management in all aspects of life", including at the workplace.[404] Michael Newman includes anarchism as one of many socialist traditions.[86] Peter Marshall argues that "[i]n general anarchism is closer to socialism than liberalism. ... Anarchism finds itself largely in the socialist camp, but it also has outriders in liberalism. It cannot be reduced to socialism, and is best seen as a separate and distinctive doctrine."[410]

Democratic socialism and social democracy

You can't talk about ending the slums without first saying profit must be taken out of slums. You're really tampering and getting on dangerous ground because you are messing with folk then. You are messing with captains of industry. Now this means that we are treading in difficult water, because it really means that we are saying that something is wrong with capitalism. There must be a better distribution of wealth, and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism.[411][412]

—Martin Luther King Jr., 1966

Democratic socialism represents any socialist movement that seeks to establish an economy based on economic democracy by and for the working class. Democratic socialism is difficult to define and groups of scholars have radically different definitions for the term. Some definitions simply refer to all forms of socialism that follow an electoral, reformist or evolutionary path to socialism rather than a revolutionary one.[413] According to Christopher Pierson, "[i]f the contrast which 1989 highlights is not that between socialism in the East and liberal democracy in the West, the latter must be recognised to have been shaped, reformed and compromised by a century of social democratic pressure". Pierson further claims that "social democratic and socialist parties within the constitutional arena in the West have almost always been involved in a politics of compromise with existing capitalist institutions (to whatever far distant prize its eyes might from time to time have been lifted)". For Pierson, "if advocates of the death of socialism accept that social democrats belong within the socialist camp, as I think they must, then the contrast between socialism (in all its variants) and liberal democracy must collapse. For actually existing liberal democracy is, in substantial part, a product of socialist (social democratic) forces".[414]

Social democracy is a socialist tradition of political thought.

Social democrats advocate a peaceful, evolutionary transition of the economy to socialism through progressive social reform.[429][430] It asserts that the only acceptable constitutional form of government is representative democracy under the rule of law.[431] It promotes extending democratic decision-making beyond political democracy to include economic democracy to guarantee employees and other economic stakeholders sufficient rights of co-determination.[431] It supports a mixed economy that opposes inequality, poverty and oppression while rejecting both a totally unregulated market economy or a fully planned economy.[432] Common social democratic policies include universal social rights and universally accessible public services such as education, health care, workers' compensation and other services, including child care and elder care.[433] Social democracy supports the trade union labour movement and supports collective bargaining rights for workers.[434] Most social democratic parties are affiliated with the Socialist International.[421]

Modern democratic socialism is a broad political movement that seeks to promote the ideals of socialism within the context of a democratic system. Some democratic socialists support social democracy as a temporary measure to reform the current system while others reject reformism in favour of more revolutionary methods. Modern social democracy emphasises a program of gradual legislative modification of capitalism to make it more equitable and humane while the theoretical end goal of building a socialist society is relegated to the indefinite future. According to Sheri Berman, Marxism is loosely held to be valuable for its emphasis on changing the world for a more just, better future.[435]

The two movements are widely similar both in terminology and in ideology, although there are a few key differences. The major difference between social democracy and democratic socialism is the object of their politics in that contemporary social democrats support a welfare state and unemployment insurance as well as other practical, progressive reforms of capitalism and are more concerned to administrate and humanise it. On the other hand, democratic socialists seek to replace capitalism with a socialist economic system, arguing that any attempt to humanise capitalism through regulations and welfare policies would distort the market and create economic contradictions.[436]

Ethical and liberal socialism

Ethical socialism appeals to socialism on ethical and moral grounds as opposed to economic, egoistic, and consumeristic grounds. It emphasizes the need for a morally conscious economy based upon the principles of altruism, cooperation, and social justice while opposing possessive individualism.[437] Ethical socialism has been the official philosophy of mainstream socialist parties.[438]

Liberal socialism incorporates liberal principles to socialism.

Principles that can be described as ethical or liberal socialist have been based upon or developed by philosophers such as

Leninism and precedents

Blanquism is a conception of revolution named for

According to Arthur Lipow, Marx and Engels were "the founders of modern revolutionary democratic socialism", described as a form of "socialism from below" that is "based on a mass working-class movement, fighting from below for the extension of democracy and human freedom". This

Trotsky viewed himself to be an adherent of Leninism but opposed the

Libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, sometimes called

Anarcho-syndicalist Gaston Leval explained:

We therefore foresee a Society in which all activities will be coordinated, a structure that has, at the same time, sufficient flexibility to permit the greatest possible autonomy for social life, or for the life of each enterprise, and enough cohesiveness to prevent all disorder. ... In a well-organised society, all of these things must be systematically accomplished by means of parallel federations, vertically united at the highest levels, constituting one vast organism in which all economic functions will be performed in solidarity with all others and that will permanently preserve the necessary cohesion".[486]

All of this is typically done within a general call for

As part of the larger socialist movement, it seeks to distinguish itself from Bolshevism, Leninism and Marxism–Leninism as well as social democracy.

Religious socialism

Christian socialism is a broad concept involving an intertwining of Christian religion with socialism.[499]

Social movements

Socialist feminism is a branch of

Many socialists were early advocates of

Eco-socialism is a political strain merging aspects of socialism, Marxism or libertarian socialism with green politics, ecology and

In the late 19th century, anarcho-naturism fused anarchism and

Syndicalism

Syndicalism operates through industrial trade unions. It rejects

Public views

A multitude of polls have found significant levels of support for socialism among modern populations.[542][543]

A 2018 IPSOS poll found that 50% of the respondents globally strongly or somewhat agreed that present socialist values were of great value for societal progress. In China this was 84%, India 72%, Malaysia 62%, Turkey 62%, South Africa 57%, Brazil 57%, Russia 55%, Spain 54%, Argentina 52%, Mexico 51%, Saudi Arabia 51%, Sweden 49%, Canada 49%, Great Britain 49%, Australia 49%, Poland 48%, Chile 48%, South Korea 48%, Peru 48%, Italy 47%, Serbia 47%, Germany 45%, Belgium 44%, Romania 40%, United States 39%, France 31%, Hungary 28% and Japan 21%.[544]

A 2021 survey conducted by the

A 2021 Axios poll found that 51% of 18-34 US adults had a positive view of socialism and 41% of Americans more generally had a positive view compared to 52% of those who viewing socialism more negatively.[546]

In 2023, the Fraser Institute published findings which found that 42% of Canadians viewed socialism as the ideal system compared to 43% of British respondents, 40% Australian respondents and 31% American respondents. Overall support for socialism ranged from 50% of Canadians 18-24 year olds to 28% of Canadians over 55.[547]

Criticism

According to analytical Marxist sociologist Erik Olin Wright, "The Right condemned socialism as violating individual rights to private property and unleashing monstrous forms of state oppression", while "the Left saw it as opening up new vistas of social equality, genuine freedom and the development of human potentials."[548]

Because of socialism's many varieties, most critiques have focused on a specific approach. Proponents of one approach typically criticise others. Socialism has been criticised in terms of its

.Some forms of criticism occupy theoretical grounds, such as in the

Critics of socialism have argued that in any society where everyone holds equal wealth, there can be no material incentive to work because one does not receive rewards for a work well done. They further argue that incentives increase productivity for all people and that the loss of those effects would lead to stagnation. Some critics of socialism argue that income sharing reduces individual incentives to work and therefore incomes should be individualized as much as possible.[555]

Some philosophers have also criticized the aims of socialism, arguing that equality erodes away at individual diversities and that the establishment of an equal society would have to entail strong coercion.[556]

Milton Friedman argued that the absence of private economic activity would enable political leaders to grant themselves coercive powers, powers that, under a capitalist system, would instead be granted by a capitalist class, which Friedman found preferable.[557]

Many commentators on the political right point to the mass killings under communist regimes, claiming them as an indictment of socialism.[558][559][560] Opponents of this view, including supporters of socialism, state that these killings were aberrations caused by specific authoritarian regimes, and not caused by socialism itself, and draw comparisons to killings and excess deaths under colonialism and anti-communist authoritarian governments.[561]

See also

- Anarchism and socialism

- Critique of work

- List of socialist parties with national parliamentary representation

- List of communist ideologies

- List of socialist songs

- List of socialist states

- Paris Commune

- Socialist democracy

- Scientific socialism

- Marxian critique of political economy

- Why Socialism? – an article written by Albert Einstein

- Types of socialism

- Zenitism

- Socialism by country (category)

References

- ^ Busky (2000), p. 2: "Socialism may be defined as movements for social ownership and control of the economy. It is this idea that is the common element found in the many forms of socialism."

- ^

- Busky (2000), p. 2: "Socialism may be defined as movements for social ownership and control of the economy. It is this idea that is the common element found in the many forms of socialism."

- Arnold (1994), pp. 7–8: "What else does a socialist economic system involve? Those who favor socialism generally speak of social ownership, social control, or socialization of the means of production as the distinctive positive feature of a socialist economic system."

- Horvat (2000), pp. 1515–1516: "Just as private ownership defines capitalism, social ownership defines socialism. The essential characteristic of socialism in theory is that it destroys social hierarchies, and therefore leads to a politically and economically egalitarian society. Two closely related consequences follow. First, every individual is entitled to an equal ownership share that earns an aliquot part of the total social dividend... Second, in order to eliminate social hierarchy in the workplace, enterprises are run by those employed, and not by the representatives of private or state capital. Thus, the well-known historical tendency of the divorce between ownership and management is brought to an end. The society—i.e. every individual equally—owns capital and those who work are entitled to manage their own economic affairs."

- Rosser & Barkley (2003), p. 53: "Socialism is an economic system characterised by state or collective ownership of the means of production, land, and capital.";

- Badie, Berg-Schlosser & Morlino (2011), p. 2456: "Socialist systems are those regimes based on the economic and political theory of socialism, which advocates public ownership and cooperative management of the means of production and allocation of resources."

- Zimbalist, Sherman & Brown (1988), p. 7: "Pure socialism is defined as a system wherein all of the means of production are owned and run by the government and/or cooperative, nonprofit groups."

- Brus (2015), p. 87: "This alteration in the relationship between economy and politics is evident in the very definition of a socialist economic system. The basic characteristic of such a system is generally reckoned to be the predominance of the social ownership of the means of production."

- Hastings, Adrian; Mason, Alistair; Pyper, Hugh (2000). The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought. ISBN 978-0198600244.

Socialists have always recognized that there are many possible forms of social ownership of which co-operative ownership is one...Nevertheless, socialism has throughout its history been inseparable from some form of common ownership. By its very nature it involves the abolition of private ownership of capital; bringing the means of production, distribution, and exchange into public ownership and control is central to its philosophy. It is difficult to see how it can survive, in theory or practice, without this central idea.

- ^ Horvat (2000), pp. 1515–1516.

- ^ Arnold (1994), pp. 7–8.

- ISBN 978-0198600244.

Socialists have always recognized that there are many possible forms of social ownership of which co-operative ownership is one...Nevertheless, socialism has throughout its history been inseparable from some form of common ownership. By its very nature it involves the abolition of private ownership of capital; bringing the means of production, distribution, and exchange into public ownership and control is central to its philosophy. It is difficult to see how it can survive, in theory or practice, without this central idea.

- ^ "Socialism". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

2. (Government, Politics & Diplomacy) any of various social or political theories or movements in which the common welfare is to be achieved through the establishment of a socialist economic system.

- ISBN 978-0-15-512403-5.

Pure socialism is defined as a system wherein all of the means of production are owned and run by the government and/or cooperative, nonprofit groups.

- ISBN 978-0-262-18234-8.

Socialism is an economic system characterised by state or collective ownership of the means of production, land, and capital.

- ^ Badie, Berg-Schlosser & Morlino (2011), p. 2456: "Socialist systems are those regimes based on the economic and political theory of socialism, which advocates public ownership and cooperative management of the means of production and allocation of resources."

- ^ Horvat (2000), pp. 1515–1516: "Just as private ownership defines capitalism, social ownership defines socialism. The essential characteristic of socialism in theory is that it destroys social hierarchies, and therefore leads to a politically and economically egalitarian society. Two closely related consequences follow. First, every individual is entitled to an equal ownership share that earns an aliquot part of the total social dividend...Second, in order to eliminate social hierarchy in the workplace, enterprises are run by those employed, and not by the representatives of private or state capital. Thus, the well-known historical tendency of the divorce between ownership and management is brought to an end. The society—i.e. every individual equally—owns capital and those who work are entitled to manage their own economic affairs."

- ISBN 978-0415241878.

In order of increasing decentralisation (at least) three forms of socialised ownership can be distinguished: state-owned firms, employee-owned (or socially) owned firms, and citizen ownership of equity.

- ^ "Left". Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 April 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

Socialism is the standard leftist ideology in most countries of the world; ... .

- Nove, Alec (2008). "Socialism". New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (Second ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

A society may be defined as socialist if the major part of the means of production of goods and services is in some sense socially owned and operated, by state, socialised or cooperative enterprises. The practical issues of socialism comprise the relationships between management and workforce within the enterprise, the interrelationships between production units (plan versus markets), and, if the state owns and operates any part of the economy, who controls it and how.

- ISBN 978-0810855601.

- ISBN 978-1412916523.

There are many forms of socialism, all of which eliminate private ownership of capital and replace it with collective ownership. These many forms, all focused on advancing distributive justice for long-term social welfare, can be divided into two broad types of socialism: nonmarket and market.

- ^ Bockman (2011), p. 20: "socialism would function without capitalist economic categories—such as money, prices, interest, profits and rent—and thus would function according to laws other than those described by current economic science. While some socialists recognised the need for money and prices at least during the transition from capitalism to socialism, socialists more commonly believed that the socialist economy would soon administratively mobilise the economy in physical units without the use of prices or money."; Steele (1999), pp. 175–177: "Especially before the 1930s, many socialists and anti-socialists implicitly accepted some form of the following for the incompatibility of state-owned industry and factor markets. A market transaction is an exchange of property titles between two independent transactors. Thus internal market exchanges cease when all of industry is brought into the ownership of a single entity, whether the state or some other organization, ... the discussion applies equally to any form of social or community ownership, where the owning entity is conceived as a single organization or administration."; Arneson (1992): "Marxian socialism is often identified with the call to organize economic activity on a nonmarket basis."; Schweickart et al. (1998), pp. 61–63: "More fundamentally, a socialist society must be one in which the economy is run on the principle of the direct satisfaction of human needs. ... Exchange-value, prices and so money are goals in themselves in a capitalist society or in any market. There is no necessary connection between the accumulation of capital or sums of money and human welfare. Under conditions of backwardness, the spur of money and the accumulation of wealth has led to a massive growth in industry and technology ... . It seems an odd argument to say that a capitalist will only be efficient in producing use-value of a good quality when trying to make more money than the next capitalist. It would seem easier to rely on the planning of use-values in a rational way, which because there is no duplication, would be produced more cheaply and be of a higher quality."

- ^ Nove (1991), p. 13: "Under socialism, by definition, it (private property and factor markets) would be eliminated. There would then be something like 'scientific management', 'the science of socially organized production', but it would not be economics."; Kotz (2006): "This understanding of socialism was held not just by revolutionary Marxist socialists but also by evolutionary socialists, Christian socialists, and even anarchists. At that time, there was also wide agreement about the basic institutions of the future socialist system: public ownership instead of private ownership of the means of production, economic planning instead of market forces, production for use instead of for profit."; Weisskopf (1992): "Socialism has historically been committed to the improvement of people's material standards of living. Indeed, in earlier days many socialists saw the promotion of improving material living standards as the primary basis for socialism's claim to superiority over capitalism, for socialism was to overcome the irrationality and inefficiency seen as endemic to a capitalist system of economic organization."; Prychitko (2002), p. 12: "Socialism is a system based upon de facto public or social ownership of the means of production, the abolition of a hierarchical division of labor in the enterprise, a consciously organized social division of labor. Under socialism, money, competitive pricing, and profit-loss accounting would be destroyed."

- S2CID 153267388.

- ISBN 978-0415241878.

Market socialism is the general designation for a number of models of economic systems. On the one hand, the market mechanism is utilized to distribute economic output, to organize production and to allocate factor inputs. On the other hand, the economic surplus accrues to society at large rather than to a class of private (capitalist) owners, through some form of collective, public or social ownership of capital.

- ISBN 978-0271-014784.

At the heart of the market socialist model is the abolition of the large-scale private ownership of capital and its replacement by some form of 'social ownership'. Even the most conservative accounts of market socialism insist that this abolition of large-scale holdings of private capital is essential. This requirement is fully consistent with the market socialists' general claim that the vices of market capitalism lie not with the institutions of the market but with (the consequences of) the private ownership of capital ... .

- ^ Newman (2005), p. 2: "In fact, socialism has been both centralist and local; organized from above and built from below; visionary and pragmatic; revolutionary and reformist; anti-state and statist; internationalist and nationalist; harnessed to political parties and shunning them; an outgrowth of trade unionism and independent of it; a feature of rich industrialized countries and poor peasant-based communities."

- ^ Ely, Richard T. (1883). French and German Socialism in Modern Times. New York: Harper and Brothers. pp. 204–205.

Social democrats forms the extreme wing of the socialists ... inclined to lay so much stress on equality of enjoyment, regardless of the value of one's labor, that they might, perhaps, more properly be called communists. ... They have two distinguishing characteristics. The vast majority of them are laborers, and, as a rule, they expect the violent overthrow of existing institutions by revolution to precede the introduction of the socialistic state. I would not, by any means, say that they are all revolutionists, but the most of them undoubtedly are. ... The most general demands of the social democrats are the following: The state should exist exclusively for the laborers; land and capital must become collective property, and production be carried on unitedly. Private competition, in the ordinary sense of the term, is to cease.

- ISBN 978-0415438209.

- ISBN 978-0230367258.

Social democracy is an ideological stance that supports a broad balance between market capitalism, on the one hand, and state intervention, on the other hand. Being based on a compromise between the market and the state, social democracy lacks a systematic underlying theory and is, arguably, inherently vague. It is nevertheless associated with the following views: (1) capitalism is the only reliable means of generating wealth, but it is a morally defective means of distributing wealth because of its tendency towards poverty and inequality; (2) the defects of the capitalist system can be rectified through economic and social intervention, the state being the custodian of the public interest ... .

- ^ Roemer (1994), pp. 25–27: "The long term and the short term."; Berman (1998), p. 57: "Over the long term, however, democratizing Sweden's political system was seen to be important not merely as a means but also as an end in itself. Achieving democracy was crucial not only because it would increase the power of the SAP in the Swedish political system but also because it was the form socialism would take once it arrived. Political, economic, and social equality went hand in hand, according to the SAP, and were all equally important characteristics of the future socialist society."; Busky (2000), pp. 7–8; Bailey (2009), p. 77: "... Giorgio Napolitano launched a medium-term programme, 'which tended to justify the governmental deflationary policies, and asked for the understanding of the workers, since any economic recovery would be linked with the long-term goal of an advance towards democratic socialism'"; Lamb (2015), p. 415

- ^ Badie, Berg-Schlosser & Morlino (2011), p. 2423: "Social democracy refers to a political tendency resting on three fundamental features: (1) democracy (e.g., equal rights to vote and form parties), (2) an economy partly regulated by the state (e.g., through Keynesianism), and (3) a welfare state offering social support to those in need (e.g., equal rights to education, health service, employment and pensions)."

- ISBN 1933567015.

- ^ Lamb & Docherty (2006), p. 1.

- ISBN 978-1931859257.

As the nineteenth century progressed, 'socialist' came to signify not only concern with the social question, but opposition to capitalism and support for some form of social ownership.

- Polity Press. p. 71.

- ^ Newman (2005), p. 5: "Chapter 1 looks at the foundations of the doctrine by examining the contribution made by various traditions of socialism in the period between the early 19th century and the aftermath of the First World War. The two forms that emerged as dominant by the early 1920s were social democracy and communism."

- ^ Kurian, George Thomas, ed. (2011). The Encyclopedia of Political Science. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. p. 1554.

- Facts on File. Inc.p. 280.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (Spring–Summer 1986). "The Soviet Union Versus Socialism". Our Generation. Retrieved 10 June 2020 – via Chomsky.info.

- S2CID 42809979. Archived from the original(PDF) on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ Fitzgibbons, Daniel J. (11 October 2002). "USSR strayed from communism, say Economics professors". The Campus Chronicle. University of Massachusetts Amherst. Retrieved 22 September 2021. See also Wolff, Richard D. (27 June 2015). "Socialism Means Abolishing the Distinction Between Bosses and Employees". Truthout. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Barrett (1978): "If we were to extend the definition of socialism to include Labor Britain or socialist Sweden, there would be no difficulty in refuting the connection between capitalism and democracy."; Heilbroner (1991), pp. 96–110; Kendall (2011), pp. 125–127: "Sweden, Great Britain, and France have mixed economies, sometimes referred to as democratic socialism—an economic and political system that combines private ownership of some of the means of production, governmental distribution of some essential goods and services, and free elections. For example, government ownership in Sweden is limited primarily to railroads, mineral resources, a public bank, and liquor and tobacco operations."; Li (2015), pp. 60–69: "The scholars in camp of democratic socialism believe that China should draw on the Sweden experience, which is suitable not only for the West but also for China. In the post-Mao China, the Chinese intellectuals are confronted with a variety of models. The liberals favor the American model and share the view that the Soviet model has become archaic and should be totally abandoned. Meanwhile, democratic socialism in Sweden provided an alternative model. Its sustained economic development and extensive welfare programs fascinated many. Numerous scholars within the democratic socialist camp argue that China should model itself politically and economically on Sweden, which is viewed as more genuinely socialist than China. There is a growing consensus among them that in the Nordic countries the welfare state has been extraordinarily successful in eliminating poverty."

- ^ Sanandaji (2021): "Nordic nations—and especially Sweden—did embrace socialism between around 1970 and 1990. During the past 30 years, however, both conservative and social democratic-led governments have moved toward the center."

- ^ Sanandaji (2021); Caulcutt (2022); Krause-Jackson (2019); Best et al. (2011), p. xviii

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica. 29 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Judis, John B. (20 November 2019). "The Socialist Revival". American Affairs Journal. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ISBN 978-1405154956.

- ^ "socialism (n.)". etymonline. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-0393-060546 – via Google Books.

- ^ OCLC 1289795802.

- ISBN 978-1285-05535-0.

Socialist writers of the nineteenth century proposed socialist arrangements for sharing as a response to the inequality and poverty of the industrial revolution. English socialist Robert Owen proposed that ownership and production take place in cooperatives, where all members shared equally. French socialist Henri Saint-Simon proposed to the contrary: socialism meant solving economic problems by means of state administration and planning, and taking advantage of new advances in science.

- ^ "Etymology of socialism". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (1972). A History of Western Philosophy. Touchstone. p. 781.

- ISBN 978-0195204698.

Modern usage began to settle from the 1860s, and in spite of the earlier variations and distinctions it was socialist and socialism which came through as the predominant words ... Communist, in spite of the distinction that had been made in the 1840s, was very much less used, and parties in the Marxist tradition took some variant of social and socialist as titles.

- ISBN 978-0875484495.

One widespread distinction was that socialism socialised production only while communism socialised production and consumption.

- ^ ISBN 978-0875484495.

By 1888, the term 'socialism' was in general use among Marxists, who had dropped 'communism', now considered an old fashioned term meaning the same as 'socialism'. ... At the turn of the century, Marxists called themselves socialists. ... The definition of socialism and communism as successive stages was introduced into Marxist theory by Lenin in 1917. ... the new distinction was helpful to Lenin in defending his party against the traditional Marxist criticism that Russia was too backward for a socialist revolution.

- ^ Busky (2000), p. 9: "In a modern sense of the word, communism refers to the ideology of Marxism–Leninism."

- ISBN 978-0195204698.

The decisive distinction between socialist and communist, as in one sense these terms are now ordinarily used, came with the renaming, in 1918, of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) as the All-Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks). From that time on, a distinction of socialist from communist, often with supporting definitions such as social democrat or democratic socialist, became widely current, although it is significant that all communist parties, in line with earlier usage, continued to describe themselves as socialist and dedicated to socialism.

- ^ ISBN 978-019-0695545.

- ISBN 978-0-006334798.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich (2002) [1888]. Preface to the 1888 English Edition of the Communist Manifesto. Penguin Books. p. 202.

- ISBN 978-1350150331.

- ^ Wilson, Fred (2007). "John Stuart Mill". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ Baum, Bruce (2007). "J. S. Mill and Liberal Socialism". In Urbanati, Nadia; Zacharas, Alex (eds.). J.S. Mill's Political Thought: A Bicentennial Reassessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mill, in contrast, advances a form of liberal democratic socialism for the enlargement of freedom as well as to realise social and distributive justice. He offers a powerful account of economic injustice and justice that is centered on his understanding of freedom and its conditions.

- ^ Principles of Political Economy with Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy, IV.7.21. John Stuart Mill: Political Economy, IV.7.21. "The form of association, however, which if mankind continue to improve, must be expected in the end to predominate, is not that which can exist between a capitalist as chief, and work-people without a voice in the management, but the association of the labourers themselves on terms of equality, collectively owning the capital with which they carry on their operations, and working under managers elected and removable by themselves."

- ^ Gildea, Robert. "1848 in European Collective Memory". In Evans; Strandmann (eds.). The Revolutions in Europe, 1848–1849. pp. 207–235.

- ISBN 978-07391-06075 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mookerji, Radhakumud. Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 102.

Kautiliya polity was based on a considerable amount of socialism and nationalisation of industries.

- ^ Taylor, A.E. (2001). Plato: The Man and His Work. Dover. pp. 276–277.

- ^ Ross, W. D. Aristotle (6 ed.). p. 257.

- ^ A Short History of the World. Moscow: Progress Publishers. 1974.

- ^ Esposito (1995), p. 19; Oxford Islamic Studies Online; Hanna & Gardner (1969), pp. 273–274; Hanna (1969), pp. 275–286

- ^ And Once Again Abu Dharr. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ISBN 978-1844671762.

- ^ Salter, Alexander William (21 April 2022). "Opinion | Jesus a Socialist? That's a Myth". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ISSN 2471-2647. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Acts 4:32–35: "32Now the whole group of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common. 33With great power the apostles gave their testimony to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and great grace was upon them all. 34There was not a needy person among them, for as many as owned lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold. 35They laid it at the apostles' feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need."

- ^ Routledge, Paul (21 May 1994). "Labour revives faith in Christian Socialism". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ a b Kurian, Thomas, ed. (2011). The Encyclopedia of Political Science. Washington D.C.: CQ Press. p. 1555.

- ISBN 0141018909.

- ISBN 978-0262-022569.

- ^ Bonnett, Alastair (2007). "The Other Rights of Man: The Revolutionary Plan of Thomas Spence". History Today. 57 (9): 42–48.

- ^ Vincent, Andrew (2010). Modern political ideologies. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 88.

- ISBN 1412904099.

- ^ Cole, G. D. H. (1953). Socialist Thought: The Forerunners. Macmillan & Co. p. 1.

- ^ Brandal, Bratberg & Thorsen (2013), p. 20.

- Encyclopedia BritannicaOnline. 29 May 2023.

The origins of socialism as a political movement lie in the Industrial Revolution.

- ^ a b c "Adam Smith". Fsmitha.com. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ "2: Birth of the Socialist Idea". Anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 7 August 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Newman (2005).

- .

In Fourier's system of Harmony all creative activity including industry, craft, agriculture, etc. will arise from liberated passion—this is the famous theory of "attractive labour." Fourier sexualises work itself—the life of the Phalanstery is a continual orgy of intense feeling, intellection, & activity, a society of lovers & wild enthusiasts....The Harmonian does not live with some 1600 people under one roof because of compulsion or altruism, but because of the sheer pleasure of all the social, sexual, economic, "gastrosophic," cultural, & creative relations this association allows & encourages.

- ISBN 978-213-0620785.