History of the socialist movement in the United Kingdom

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

Socialism in the United Kingdom is thought to stretch back to the 19th century from roots arising in the aftermath of the

Origins

The

19th century

Industrial Revolution and Robert Owen

The Industrial Revolution, the transition from a farming economy to an industrial one, began in the UK over thirty years before the rest of the world. Textile mills and coal mines sprang up across the whole country and peasants were taken from the fields to work down the mines, or into the "Dark, Satanic Mills", the chimneys of which blackened the sky over Lancashire and Yorkshire. Appalling conditions for workers, combined with support for the French Revolution, turned some intellectuals to socialism.

The pioneering work of

Trade unions

The trade union movement in Britain gradually developed from the Medieval

From 1830 on, attempts were made to set up national general unions, most notably Robert Owen's Grand National Consolidated Trades Union in 1834, which attracted a range of socialists from Owenites to revolutionaries. It played a part in the protests after the Tolpuddle Martyrs' case, but soon collapsed.

Militants turned to Chartism, the aims of which were supported by most socialists, although none appear to have played leading roles.

More permanent trade unions were established from the 1850s, better resourced but often less radical. The London Trades Council was founded in 1860, and the Sheffield Outrages spurred the establishment of the Trades Union Congress in 1868. Union membership grew as unskilled and women workers were unionised, and socialists such as Tom Mann played an increasingly prominent role.

Christian socialism

The rise of Non-Conformist religions, in particular Methodism, played a large role in the development of trade unions and of British socialism. The influence of the radical chapels was strongly felt among some industrial workers, especially miners and those in the north of England and Wales.

The first group calling itself

Chartist movement

The

The Chartists published several petitions to the British Parliament (ranging from 1,280,000 to 3,000,000 signatures), the most famous of which was called the People's Charter (hence their name) in 1842, which demanded:[10]

- Universal suffrage for men.

- The secret ballot.

- Removal of property qualifications for members of parliament.

- Salaries for members of parliament.

- Electoral districts representing equal numbers of people.

- Annually elected parliaments.

The government subsequently subjected the Chartists to brutal reprisals and arrested their leaders. The remaining party then split as a result of a divide in tactics: the Moral Force Party believed in bureaucratic reformism, while the Physical Force Party believed in workers' reformism (through strikes, etc.).

The Chartist movement's reformist goals, although not immediately and directly attained, were gradually achieved. In the same year as the People's Charter was created, the

Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Marxism

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels worked in England, and they influenced small émigré groups including the Communist League. Engels' book The Condition of the Working Class in England[12] became a popular expose of conditions for workers, but initially Marxism had little impact among Britain's working class.

The first nominally Marxist organisation was the Social Democratic Federation, founded in 1882. Engels refused to support the organisation, although Marx's daughter Eleanor joined.

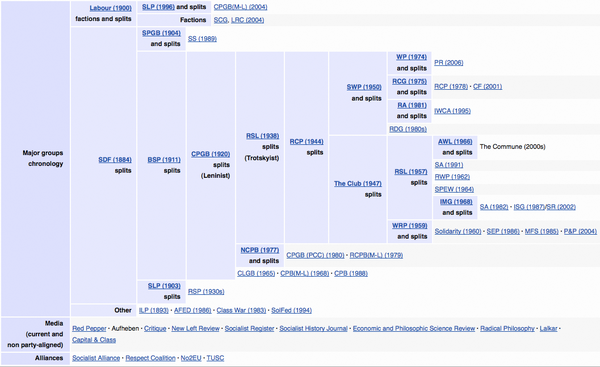

The party soon split, with the Socialist League of William Morris becoming divided between anarchists and Marxists such as Morris and Eleanor Marx. A much later split produced the Socialist Party of Great Britain, Britain's oldest existing socialist party, and the Socialist Labour Party.

Although Marxism had some impact in Britain, it was far less than in many other European countries, with philosophers such as John Ruskin and John Stuart Mill having much greater influence. Some non-Marxists[who?] theorise that this was because Britain was amongst the most democratic countries of Europe of the period, the ballot box provided an instrument for change, so a parliamentary, reformist socialism seemed a more promising route than elsewhere.

Liberal–Labour and the Independent Labour Party

The

However, a great deal of collaboration came to exist between the Liberal Party and the leaders of the labour movement, though Marx saw these as effective bribes by the bourgeoisie and the government.

In 1874, the Liberals agreed not to put candidates against

In 1888,

At the 1892 general election, Keir Hardie, another Liberal politician who had joined Cunninghame-Graham in the Scottish Labour Party, was elected as an Independent Labour MP, and this gave him the spur to found a UK-wide Independent Labour Party in 1893.

20th century

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

The early twentieth century saw a number of socialist groups and movements in Britain. As well as the Independent Labour Party and the Social Democratic Federation, there was a mass movement around

Birth of the Labour Party

In 1900, representatives of various trade unions and of the Independent Labour Party, Fabian Society and Social Democratic Federation agreed to form a Labour Party backed by the unions and with its own whips. The

The LRC affiliated to the

Women's suffrage

The campaign for women's suffrage in Britain began in the mid-nineteenth century, with many early campaigners including Eleanor Marx being socialists, but many established socialists, including Robert Blatchford and

Syndicalism and World War I

Supporters of

This activity took place against the background of the

Bolshevism and the Communist Party of Great Britain

The shop steward movement worried many right-wingers, who believed that socialists were fomenting a

The CPGB soon became known for its loyalty to the line of the

Labour and the general strike

The Labour Party continued to grow as more unions affiliated and more Labour MPs were elected. In 1918, a new constitution was agreed, which laid out several aims of the party. These included

In 1926, British miners went on strike over their appalling working conditions. The situation soon escalated into the

Labour formed a minority government in

The Great Depression devastated the industrial areas of Northern England, Wales and Central Scotland, and the Jarrow March of unemployed workers from the North East to London to demand jobs defined the period.

Ethical socialism

Ethical socialism is a variant of liberal socialism developed by British socialists.[17][18] It became an important ideology within the Labour Party of the United Kingdom.[19] Ethical socialism was founded in the 1920s by R. H. Tawney, a British Christian socialist, and its ideals were connected to Christian socialist, Fabian, and guild socialist ideals.[20] Ethical socialism has been publicly supported by British Prime Ministers Ramsay MacDonald,[21] Clement Attlee,[22] and Tony Blair.[19]

Oswald Mosley

Spanish Civil War and World War II

The Independent Labour Party disaffiliated from the Labour Party in 1932, in protest at an erosion of their MPs' independence. For a time, they became a significant left-of-Labour force.

In 1936, the

The Labour Party leadership always supported British involvement in

1945 landslide Labour victory

To widespread surprise, the Labour Party led by wartime Deputy Prime Minister

The CPGB also grew on the back of Stalinist successes in Eastern Europe and China, and recorded their best-ever result, with two MPs elected (one in London and another in Fife). The Trotskyite Revolutionary Communist Party collapsed.

Labour lost power in 1951 and after Clement Attlee retired as party leader in 1955, he was succeeded by the figurehead of the "right-establishment" Hugh Gaitskell, against Aneurin Bevan.

Although there were some disputes between the

1960s and 1970s

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament briefly gained leverage over Labour Party policy at the beginning of the decade, but soon went into a long eclipse. The Vietnam War, given lukewarm support by Harold Wilson, radicalised a new generation. Significant anti-war protests were organised. Trotskyist groups like the International Marxist Group and the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign came to prominence, particularly due to high-profile members like the IMG's Tariq Ali.

After the Soviet Union's invasion of

In 1969, Wilson's Labour Government introduced

1980s

After the 1979 Labour defeat,

In 1981, thirty MPs on the right-wing of the Labour Party defected to found the

At the

After the 1983 general election, Neil Kinnock, long associated with the left-wing of the Labour Party, became the new leader. By that point in time, the Labour Party was factionalised between the right, including Healey and deputy leader Roy Hattersley, a "soft left" associated with the Tribune group, and a "hard left" associated with Benn and the new Campaign Group.

The Trotskyist Militant tendency, using entryist tactics in the Labour Party, had gradually increased their profile. By 1982, they controlled Liverpool City Council, and had a presence in many Constituency Labour Parties. The Labour NEC began to expel Militant members, beginning with their newspaper's "editorial board", in effect their Central Committee. A revival in municipal socialism seemed, for a time, a solution to Conservative hegemony for many on the left. The Greater London Council, led by Ken Livingstone, gained the most attention, seeming genuinely innovative to its support base, but the GLC was abolished by the Conservatives in 1986.

The defining event of the 1980s for British socialists was the

Socialism and nationalism

The early nationalist parties had little connection with socialism, but by the 1980s they had become increasingly identified with the left, and in the 1990s Plaid Cymru declared itself to be a socialist party.

Following the establishment of the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Parliament (established as the National Assembly for Wales), both the Scottish National Party and Plaid have been challenged by socialists in recent years. [clarification needed] The Scottish Socialist Party, who also support Scottish independence as an immediate goal, has had recent electoral success; it won six MSPs in the 2003 Scottish Parliament election. Forward Wales, with a less militant programme, aimed to replicate their success.

Irish republicanism came to be supported by socialists in Britain. Labour's election manifestos for 1983, 1987 and 1992 included a commitment to Irish unification by consent.

1990s

In 1989 in

The CPGB dissolved itself in 1991, although their former newspaper, the

In the run-up to the 1992 general election, polling showed that there might be a hung parliament, but possibly a small Labour majority – the party's lead on the opinion polls had shrunk and some polls had even seen the Tories creep ahead in spite of the deepening recession. In the event, the Conservatives led by John Major; won a fourth consecutive election with a majority of 21 seats. This has been attributed to both the Labour Party's premature triumphalism (in particular at the Sheffield Rally) and the Tories' "Tax Bombshell" advertising campaign, which highlighted the increased taxes that a Labour government would impose. This general election defeat was shortly followed by Kinnock's resignation after nearly a decade as leader. And, as had happened in the aftermath of the 1959 general election defeat, there was widespread public and media doubt as to whether a Labour government could be elected again, since it had failed in the face of a recession and rising unemployment.[25]

After the brief stewardship of John Smith in the early 1990s, Tony Blair was elected leader following Smith's sudden death from a heart attack in May 1994. He immediately decided to revamp Clause IV, dropping Labour's commitment to public ownership of key industries and utilities, along with other socialist policies.[26]

Many members of the party were unhappy with the proposed changes and several unions considered using their block vote to kill the motion, but in the end their leaderships backed down and settled for a new clause declaring the Labour Party a "democratic socialist party", broadening the party's electoral appeal. However, Labour had been ascendant in the opinion polls since the Black Wednesday economic fiasco a few months after the 1992 general election, and the increased lead of the polls under Blair's leadership remained strong in spite of the revolt, and the fact that the economy was growing again and unemployment was falling under Major's Conservative government. Labour's popularity was also helped by the fact that the Conservative government was now divided over Europe.[27]

Several party members, such as Arthur Scargill, regarded this as a betrayal of Labour's ideology and left the Labour Party. Scargill formed the Socialist Labour Party (SLP) which initially attracted some support, much of which transferred to the Socialist Alliance on its formation, but the SA has since been wound up and the SLP has become marginalised.[citation needed]

The Scottish Socialist Party have proven much more successful, while Ken Livingstone became the Mayor of London, standing against an official Labour Party candidate. Livingstone was re-admitted into the Labour Party in time for his re-election in 2004.

Under Blair, Labour launched a PR campaign to rebrand as New Labour. The party also introduced women-only shortlists in certain seats and central vetting of Parliamentary candidates to ensure that its candidates were seen as on-message. Labour won the 1997 general election with a landslide majority of 179 seats; their best result to date.[28]

21st century

The international

Several minor socialist parties merged in 2003 to form the Alliance for Green Socialism which is a socialist party that campaigns on a wide variety of policies including; economic, environmental and social.

After

In 2013, director

2010 general election

The Labour Party was defeated at the

Other socialists[

The Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) was formed in January 2010 to contest the 2010 general election. Founding supporters include Bob Crow, general secretary of the Rail, Maritime and Transport workers union (RMT), Brian Caton, general secretary of the POA and Chris Baugh, assistant general secretary of the PCS. RMT and Socialist Party executive members, including Bob Crow, form the core of the steering committee. The coalition includes the Socialist Workers Party, which will also stand candidates under its banner,[35] RESPECT[36] and other trade unionists and socialist groups. This followed the No2EU coalition which fought the European elections in 2009 gaining the official backing of the RMT. The RMT declined to officially back the new TUSC coalition, but granted their branches the right to stand and fund local candidates as part of the coalition.[37]

2014 Scottish independence referendum

The Scottish Socialist Party (SSP) has been actively campaigning for Scottish independence since the announcement of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum. Its co-convenor, Colin Fox, sits on the advisory board of the Yes Scotland campaign organisation. The party's support for Scottish independence is rooted in a belief that "the tearing of the blue out of the Union Jack and the dismantling of the 300-year-old British state would [be] a traumatic psychological blow for the forces of capitalism and conservatism in Britain, Europe and the USA", and that it would be "almost as potent in its symbolism as the unravelling of the Soviet Union at the start of the 1990s". Representatives of the party have also claimed that while the break-up of the United Kingdom would not result in "instant socialism", it would cause "a decisive shift in the balance of ideological and class forces".[38]

The campaign for independence has also enjoyed support from a minority of trade unionists. In 2013, a branch of the

Until 2006, the RMT was affiliated with the Scottish Socialist Party.[41]

The Labour Party campaigned in favour of a "No" vote through the referendum campaign, headed by former Labour

2015 general election

Miliband's election as Leader of the Labour Party on the back of trade union member votes had been seen by some[

2017 general election

Jeremy Corbyn became Leader of the Labour Party in September 2015. Corbyn identifies as a democratic socialist.[49]

In August 2015, prior to the 2015 leadership election, the Labour Party reported 292,505 full members.[50][51] As of December 2017[update], the party had approximately 570,000 full members, making it the largest political party by membership in Western Europe.[52][53]

On 18 April 2017, Prime Minister

In July 2017, opinion polling suggested Labour leads the Conservatives, 45% to 39%[60] while a YouGov poll gave Labour an 8-point lead over the Conservatives.[61]

Post 2019 General Election

Following the 2019 United Kingdom general election and Keir Starmer's winning of the Labour Party leadership in the 2020 leadership election, socialists in the Labour Party have been marginalised or expelled.[62] There has however been an uptick in industrial action.[63]

Leaders

- Annie Besant

- G. D. H. Cole

- Keir Hardie

- Henry Hyndman

- Ramsay MacDonald

- John Maclean

- Tom Mann

- Charles Marson

- William Morris

- Sydney Olivier

- Robert Owen

- Sylvia Pankhurst

- Edward R. Pease

- George Bernard Shaw

- Graham Wallas

- Beatrice Webb

- Sidney Webb

- H. G. Wells

See also

- History of socialism

- British Left

- Socialist Students

References

- ^ Engels, Friedrich (1970) [1880]. "I: The Development of Utopian Socialism". Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Progress Publishers – via Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^ Empson, Martin (5 April 2017). "A common treasury for all: Gerrard Winstanley's vision of utopia". International Socialism. No. 154. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-61530-062-4.

- ISBN 0-684-80577-4.

- ^ Johnson, Daniel (1 December 2013). "Winstanley's Ecology: The English Diggers Today". Monthly Review. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-89869-678-3. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- JSTOR j.ctt17w8h53.

- ^ "Minute Book of the London Working Men's Association". British Library. 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Williams, David (1939). John Frost: A Study in Chartism. Cardiff: University of Wales Press Board. pp. 100, 104, 107.

- ^ "The six points | chartist ancestors". Chartist Ancestors. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ "Glossary of Organisations: Chartists (Chartism)". Marxists Internet Archive Encyclopedia of Marxism. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich. "Conditions of the Working-Class in England Index". Marx/Engels Internet Archive. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ ISBN 0905400151.

- ^ Marx, Karl (31 August 1866). Letter to Becker.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1976). Minutes and Documents of the Hague Congress of the First International. Progress Publishers. p. 124.

- ISBN 9781786940025.

- ^ Dearlove, John; Saunders, Peter (2000). Introduction to British politics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 427.

- ^ Thompson 2006, p. 52.

- ^ a b Tansey, Stephen D.; Jackson, Nigel A. (2008). Politics: the basics (Fourth ed.). Oxon, England, UK; New York City, USA: Routledge. p. 97.

- ^ Thompson 2006, pp. 52, 58, 60..

- ^ Morgan, Kevin (2006). Ramsay MacDonald. London, England: Haus Publishing Ltd. p. 29.

- ^ Howell, David (2006). Attlee. London, England: Haus Publishing Ltd. pp. 130–132.

- ^ "1983: Thatcher triumphs again". BBC News. 5 April 2005. Archived from the original on 16 February 2006.

- ^ "1987: Thatcher's third victory". BBC News. 5 April 2005. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013.

- ^ "1992: Tories win again against odds". BBC News. 5 April 2005. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013.

- ^ "Britain Since 1948". www.localhistories.org. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ "YouGov | Unity: Parties divided". YouGov: What the world thinks. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ "1997: Labour landslide ends Tory rule". BBC News. 15 April 2005. Archived from the original on 4 February 2008.

- ^ "Galloway expelled by Labour". BBC News. 24 October 2003. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "Shock win for Galloway in London". BBC News. 6 May 2005.

- ^ "George Galloway wins Bradford West by-election". BBC News. 30 March 2012.

- ^ Tempest, Matthew (17 February 2004). "Monbiot quits Respect over threat to Greens". The Guardian.

- ^ Woodcock, Andrew (12 September 2012). "Respect chief Salma Yaqoob quits over George Galloway rape row". The Independent.

- ^ "David Cameron and Nick Clegg pledge 'united' coalition". BBC News. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "Party Notes". 25 January 2010. Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ^ "Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition". 17 January 2010. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition gets started". 19 January 2010. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021.

Portsmouth RMT stands in election with Bob Crow's support

- ^ "Why the left should back independence". 19 May 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ "Scottish postal workers hope to deliver Yes vote for independence". STV News. 4 March 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ "A Just Scotland – STUC publishes interim report on Scotland's constitutional future". 25 November 2012. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ "RMT disaffiliates from Scottish Socialist Party". RMT. 27 October 2006. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ McAlpine, Joan (25 September 2012). "Even loyal labour voters won't back No campaign". Daily Record. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "Election results: Ed Miliband steps down as Labour leader". BBC News. 8 May 2015.

- ^ "'Red Ed? Come off it', says Labour leader Miliband". BBC News. 28 September 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "Labour calls for 'responsible and better' capitalism". BBC News. 7 January 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ Clark, Liat (22 May 2013). "Ed Miliband: Google should pay more tax, engage in 'responsible capitalism'". Wired UK. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ Watt, Nicholas (26 June 2013). "Ed Balls hits out at Tories but accepts some cuts in Labour's balancing act". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ Tapsfield, James (9 June 2013). "Ed Balls facing state pension cut claims". The Scotsman. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "How Jeremy Corbyn Would Govern Britain". The Atlantic. 18 August 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ Wright, Oliver (10 September 2015). "Labour leadership contest: After 88 days of campaigning, how did Labour's candidates do?". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

the electorate is divided into three groups: 292,000 members, 148,000 union "affiliates" and 112,000 registered supporters who each paid £3 to take part

- ^ Bloom, Dan (25 August 2015). "All four Labour leadership candidates rule out legal fight – despite voter count plummeting by 60,000". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

total of those who can vote now stands at 550,816 ... The total still eligible to vote are now 292,505 full paid-up members, 147,134 supporters affiliated through the unions and 110,827 who've paid a £3 fee.

- ^ Waugh, Paul (13 June 2017). "Labour Party Membership Soars By 35,000 in Just Four Days – After 'Corbyn Surge' In 2017 General Election". Huffington Post. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ "A Snap Election, A New Leader in Scotland And A "Staggering" Rise in Membership – Alice Perry's Latest NEC Report". 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Theresa May seeks general election". BBC News. 18 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ "Corbyn welcomes PM's election move". Sky News. 18 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Stone, Jon (18 April 2017). "Jeremy Corbyn welcomes Theresa May's announcement of an early election". The Independent. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Travis, Alan (11 June 2017). "Labour can win majority if it pushes for new general election within two years". The Guardian.

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (9 June 2017). "Corbyn gives Labour biggest vote share increase since 1945". The London Economic. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Bulman, May (13 June 2017). "Labour Party membership soars by 35,000 since general election". The Independent. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ "Theresa May's ratings slump in wake of general election – poll". The Guardian.

- ^ "How excited should Labour be about its 8-point poll lead?". New Statesman.

- ^ "Keir Starmer's allies purging Labour left, says John McDonnell". BBC News. 4 July 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ "The impact of strikes in the UK - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

Bibliography

- Thompson, Noel W. (2006). Political economy and the Labour Party: the economics of democratic socialism, 1884–2005 (2nd ed.). Oxon, England, UK; New York City, USA: Routledge.

Further reading

- Barrow, Logic and Bullock, Ian. Democratic Ideas and the British Labour Movement (Cambridge University Press, 1996)

- Beilharz, Peter. Labour's Utopias: Bolshevism, Fabianism and Social Democracy (Routledge 1992)

- Biagini, E.F. and Reid, A.J., eds. Currents of Radicalism: Popular Radicalism, Organized Labour and Party Politics in Britain 1850–1914, (Cambridge University Press, 1991)

- Black, L. The Political Culture of the Left in Affluent Britain, 1951–64: old Labour, new Britain? (Basingstoke, 2003)

- Bonin, Hugo. "Between Panacea and Poison: 'democracy' in British socialist thought, 1881–1891." Intellectual History Review (2020): 1-21.

- Bryant, C. Possible Dreams: a personal history of British Christian Socialists (London, 1996)

- Callaghan, John. Socialism in Britain since 1884 (Blackwell, 1990)

- Hargreaves, John. "Sport and socialism in Britain." Sociology of sport journal 9.2 (1992): 131–153.

- McKernan, James A. "The origins of critical theory in education: Fabian socialism as social reconstructionism in nineteenth-century Britain." British Journal of Educational Studies 61.4 (2013): 417–433.

- Manton, Kevin. Socialism and education in Britain 1883-1902 (Routledge, 2013).

- Miller, Kenneth E. Socialism and Foreign Policy: Theory and Practice in Britain to 1931 (Springer, 2012).

- Morgan, Kenneth O.Ages of Reform: Dawns and Downfalls of the British Left (I.B. Tauris, dist. by Palgrave Macmillan; 2011), history of British left since the Great Reform Act, 1832.

- Parker, Martin, et al. The Dictionary of Alternatives (Zed Books, 2007)

- Rees, Jonathan.Proletarian Philosophers: Problems in Socialist Culture in Britain 1900–1940 (Oxford, 1984)

- Rosen, Greg, ed. Dictionary of Labour Biography. Politicos Publishing, 2001, 665pp; short biographies.

- Williams, Anthony A. J. Christian Socialism as Political Ideology: The Formation of the British Christian Left, 1877-1945 (Bloomsbury, 2020).

- Winter, Jay M. Socialism and the Challenge of War: Ideas and Politics in Britain, 1912-18 (Routledge, 2014) excerpt.

- Yeo, Stephen. "A new life: the religion of socialism in Britain, 1883–1896." History Workshop Journal 4#1 (1977).

Women

- Bruley, Sue. Leninism, Stalinism and the Women's Movement in Britain, 1920–1939 (Garland, London and New York, 1986)

- Graves, Pamela M. Labour Women: Women in British Working-Class Politics 1918–1939 (Cambridge University Press, 1994)

- Hannam, Julie. Socialist Women: Britain 1880s to 1920s (Routledge, 2002)

- Jackson, Angela. British Women and the Spanish Civil War (Routledge 2002

- Mitchell, Juliet, and Ann Oakley, (eds). The Rights and Wrongs of Women (Penguin, London, 1976)

- Rowbotham, Sheila. Hidden from History: 300 Years of Women's Oppression and the Fight Against It (Pluto Press, London, 1973)

Labour Party

- Bassett, Lewis. "Corbynism: Social democracy in a new left garb." Political Quarterly 90.4 (2019): 777-784 online[dead link].

- Durbin, Elizabeth. New Jerusalems: the Labour Party and the economics of democratic socialism (Routledge, 2018).

- Lyman, Richard W. "The British Labour Party: The Conflict between Socialist Ideals and Practical Politics between the Wars". Journal of British Studies 5#1 1965, pp. 140–152. online

- Pelling, Henry and Alastair J. Reid. A Short History of the Labour Party (12th ed. 2005) excerpt

- Taylor, Robert. The Parliamentary Labour Party: A History 1906–2006 (2007).

Communist Party of Great Britain

Far-left

External links

- "Alternative Pleasures", Mark Bevir, Berfrois, 25 October 2011

- "History of British Socialism", Max Beer, 1920