Sociology of sport

| Part of a series on |

| Sociology |

|---|

|

Sociology of sport, alternately referred to as sports sociology, is a sub-discipline of

Sport is regulated by

The emergence of the sociology of sport (though not the name itself) dates from the end of the 19th century, when first social psychological experiments dealing with group effects of competition and pace-making took place. Besides cultural anthropology and its interest in games in the human culture, one of the first efforts to think about sports in a more general way was Johan Huizinga's

It is a common assumption that sports can be viewed as a ritual and a game at the same time. Sports as a result can be viewed as a parallel ritual process which is connected to leisure time and freedom. The symbolic effect of a ritual allows classification of social relationships among men and between women and men, as well as the impact sports has on nations. Some national sports like baseball in Cuba, cricket in the West Indies, and football in a majority of Latin American countries drive passion that goes past the ethnic status, regional origins, or class lines. Therefore, sport is an important field of analysis for achieving better understanding of the functioning of modern societies.[4]

Race and sports

1936 Berlin Games

There was controversy around the

Adolf Hitler agreed with the proposition people who had ancestors who "came from the jungle" were "primitive because their physiques were stronger than those of civilized whites."[5] and wanted to impose racial segregation on the games, but the Olympic Committee refused. The Nazi regime did, however, use any results they could to propagandize the superiority of what they called the Aryan race.

Historical racist theories

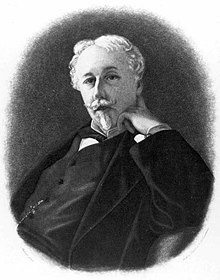

Sport has always been characterized by racial social relationships. The first scientific look at race came at the end of the 19th century, when count Arthur de Gobineau attempted to prove the physical and intellectual superiority of the white race. Darwin's theory of natural selection was used in service of racism as well. After the athletic ability of black sportspeople was proven, the theory shifted toward physical ability at the expense of intellect.[6]

Several racist theories were advanced. Black people were athletically able because animals ate all the slow ones.

Current sociology

Young

Race is often connected to gender, with women having less opportunities to access and succeed in sports. Once a woman does succeed, her race is downplayed and her sexuality is accentuated.[12] In certain cultures, especially Muslim ones, women are denied access to sports all-together.[13]

In team sports, white players are often placed in central positions which demand intelligence, decisiveness, leadership, calmness and reliability. Black players are in turn place in positions that demand athletic ability, physical strength, speed and explosiveness. For example, white players in the role of central midfielders and black players as wingers.[14]

Gender in sports

Female participation in sports is influenced by patriarchal ideologies surrounding the body, as well as ideas of femininity and sexuality. Physical exertion inevitably leads to development of muscle, which is connected to masculinity, which is in contrast to the idea of women as presented by modern consumer culture. Women who enter sports early are more likely to challenge these stereotypes.[15]

Jennifer Hargreaves sees three political strategies for women in sports:[18]

- Liberal feministsbelieve women will gradually take over more roles within sport created and controlled by men.

- radical feminists, which advocates self-realization through organization of sport events and governing bodiesindependent of men. It would further increase the number of women competing in various sports.

- socialist feministswho believe that cooperation between men and women would help to establish new sporting models that would negate gender differences. They recognize the diversity of struggles within modern capitalist societies, and aims at liberation from them. Unlike separatism it engages with men, and is more extensive than co-option. Co-operation posits that men are not inherently oppressive, but are socialized into reproducing oppressive roles.

Theories in sociology of sport

Functionalism

Structural functionalist theories see society as a

Bromberger saw similarities between religious ceremonies and football matches. Matches are held in a particular spatial configuration, pitches are sacred and may not be polluted by pitch invaders, and lead to intense emotional states in fans. As with religious ceremonies, spectators are spatially distributed according to social distribution of power. Football seasons have a fixed calendar. Group roles on match day are ceremonial, with specially robed people performing intense ritual acts. As a church, football has an organizational network, from local to global levels. Matches have a sequential order that guides the actions of participants, from pre-match to post-match actions. Lastly, football rituals create a sense of communitas.[21] Songs and choreography can be seen as an immanent ceremony through which spectators transfer their strength to the team.[22]

Accounting for the fact that not all actions support the existing societal structure, Robert K. Merton saw five ways a person could react to the existing structure, which can be applied to sports as well: conformism, innovation, ritualism, withdrawal, and rebellion.[23]

Erving Goffman drew on Durkheim's conception of positive rituals, emphasizing the sacred status of an individual's "face". Positive (compliments, greetings, etc.) and negative (avoiding confrontation, apologies, etc.) rituals all serve to protect one's face.[24] Sport journalists, for example, utilize both the positive and negative rituals to protect the face of the athlete they wish to maintain good relations with. Birrell furthermore posits sport events are ritual competitions in which athletes show their character through a mix of bravery, good play and integrity. A good showing serves to reinforce the good face of the athlete.[25]

Interpretative sociology

Interpretative sociology explores the interrelations of social action to status, subjectivity, meaning, motives, identities and social change. It avoids explaining human groups through general laws and generalizations, preferring what Max Weber called verstehen - understanding and explaining individual motivations.[26] It allows for a more complete understanding of diverse social meanings, symbols and roles within sport. Sport allows for creation of various social identities within the framework of a single game or match, which may change during it or throughout the course of multiple matches.[27] Ones role as a sportsperson further affects how they act outside of a game or a match, i.e. acting out the role of a student athlete.[28]

Weber introduced the notion of rationalization. In modern society, relationship are organized to be as efficient as possible, based on technical knowledge, instead of moral and political principles. This creates bureaucracies that are efficient, impersonal and homogeneous.[29] Allen Guttmann identified several key aspects of rationalization, which can likewise be applied to sports:[30][31]

- superstitions and prayer.

- Olympics excluded women and non-citizens. In contrast, modern sports offer opportunities to the disadvantaged, while fair judging/refereeing offer a level playing field. Social statusstill plays a role in sport access and success. Richer countries will have more numerous and successful athletes, while the higher class will have access to better training and preparation.

- Specialization: modern sports, just like industry, has a complex division of labor. Athletes have a very specialized role inside of a team, which they must learn and perform, i.e. the kicker in american football. This does not apply to all sports, as some value the ability to cover a number of roles as necessary.

- Rationalization: modern sports identify the most efficient way to achieve the desired goal. On the other hand, Giulianotti points out that sports are dominated by irrational actions.

- Bureaucratization: sports are controlled by organizations, committees and supervisory boards on local, continental and global levels. Leading positions are supposed to be given based on qualifications and experience, instead of charisma and nepotism. This is not always the case, as powerful and charismatic personage are often put in charge of said organizations and committees.

- Quantification: Statistics measure and compare modern sport events, often throughout multiple generations, reducing complex events to understandable information which can be easily grasped by the mass public. Statistics are not the dominant factor in sport culture, with the socio-psychological and aesthetically pleasing factors still being the most important.

Neo-Marxism

Specialized division of labor force athletes to constantly perform the same movements, instead of playing creatively, experimentally and freely.[34] The athlete if often under the illusion of being free, unaware of losing control over his labor power.[35] Spectators themselves support the alienation of athletes' labor through their support and participation.[36]

Marxist theories have been used to research the commodification of sport, for example, how players themselves become goods or promote them,[37] the hyper-commercialization of sports during the 20th century,[38] how clubs become like traditional firms, and how sport organizations become brands.[39]

This approach has been criticized for their tendency toward raw economism,[40] and supposing that all current social structures function to maintain the existing capitalist order.[41] Supporting sport teams does not necessarily contradict the development of class consciousness and participating in the class struggle.[42] Sport events have a number of examples of political protest. Neo Marxist analysis of sports often underestimate the aesthetic side of sport as well.

Cultural studies

Hegemony research describes the relations of power, as well as methods and techniques used by dominant groups to achieve ideological consent, without resorting to physical coercion. This ideological consent aims to make the exploratory social order seem natural, guaranteeing that the subordinate groups live out their subordination. A hegemony is always open to contestation, and thus counter-hegemonic movements may emerge.[43]

The dominant groups may use sports to steer the use of the subordinate classes in the desired direction,[44] or towards consumerism.[45] However, the history of sport shows that colonized are not necessarily manipulated through sport,[46] while sport professionalization, and their own popular culture, helped the working class avoid mass subordination to bourgeois values.[47]

Resistance is a key concept in cultural studies, which describes how subordinate groups engage in particular cultural practices to resist their domination. Resistance can be overt and deliberate or latent and unconscious, but always counters the norms and conventions of the dominant groups.[48] John Fiske differentiated between confrontational semiotics and avoidance.[49]

Body and sports

Body became a subject of research in the 80s, with the work of Michel Foucault. For him, power is exercise in two different ways - through biopower and disciplinary power. Biopower centers on the political control of key biological aspects of the human body and whole populations, such as birth, reproduction, death, etc. Disciplinary power is exercised by means of the everyday disciplining of bodies, particularly through controlling time and space.[50][51]

Eichberg sees three different types of bodies as highlighting the difference between disciplined and undisciplined bodies in sport: the dialogic body, of different shapes and sizes, which are given to freeing oneself from control, and were the main type in pre-modern festivals and carnivals. The streamlined, improved body for sports accomplishment and competition. The healthy, straight body, which is shaped through disciplined regimes of fitness. The grotesque body could be seen in pre-modern festivals and carnivals, i.e. folk wrestling or three-legged race.[52] Modern sport pedagogy fluctuates between strictness and freedom, discipline and control, but the hierarchical relations of power and knowledge between the coach and athlete remain.[53]

Segel claimed that the cultural raise of sports reflected the wider turn of modern society toward physical expression, which revived militarism, war and fascism.[54] Some representatives of the Frankfurt school, saw sport as a cult of the fascistic idea of the body.[55] Tännsjö claimed that overly complimenting sport prowess reflects the fascistic elements in society, as it normalizes the ridicule of the weak and defeated.

Sports and injury

Despite this, athletes are still thought to ignore and attempt to overcome pain, as overcoming pain is seen as brave and heroic. The capacity of the athlete to make the body seem invincible is an integral part of sports professionalism.[62] This ignoring of pain is often a key part of some sport subcultures.[63] Children are also often exposed to acute pain and injuries, i.e. gymnastics.[64]

Emotion in sports

Emotion has always been a huge part of sports as it can affect both athletes and the spectators themselves. Theorists and sociologists who study the impact of emotions in sports try to classify emotions into categories. Controversial, debated, and discussed intensely, these classifications are not definitive or set in stone. Emotion is very important in sports; athletes can use them to convey specific and significant information to their teammates and coaches and they can use emotion to send false signals to confuse their opponents. In addition to athletes using emotion to their advantage, emotion can also have a negative impact on athletes and their performances. For example, "stage fright," or nervousness and apprehension, can impact their performance in their sport, be it in a positive or negative way.[65]

Depending on the level of sports, the level of emotion differs. In professional sports, emotions can be extremely intense because there are many more people in many distinct roles who are involved. There are the professional athletes, the coaching staff, the referees, the television crew, the commentators, and last but not least, the fans and spectators. There is much more public press, pressure, and self-pressure. It is extremely difficult to not get emotionally invested in sports; sports are very good at bringing out the worst qualities in people. There have been violent brawls when one team beats another in an intense game, loud fighting and yelling, and intense verbal arguments as well. Emotion is also highly contagious, especially if there are many emotional people in one space.[66]

Binary divisions within sports

There are many perspectives through which sport can be viewed. Therefore, very often some binary divisions are stressed, and many sports sociologists have shown that those divisions can create constructs within the ideologies of gender and affect the relationships between genders, as well as advocate or challenge social and racial class structures.[67] Some of these binary divisions include: professional vs. amateur, mass vs. top-level, active vs. passive/spectator, men vs. women, sports vs. play (as an antithesis to organized and institutionalized activity).

Not only can binary divisions be seen within sports themselves, but they are also seen in the research of sports. The field of research has mainly been dominated by men because many[citation needed] believe that women's input or research is inauthentic compared to men's research. Some women researchers also feel as though they have to "earn" their place within the sports research field whereas men, for the most part, do not. While women researchers in this field do have to deal with gender-related issues when it comes to their research, it does not prevent them from being able to gather and understand the data they are collecting. Sports sociologists believe that women can have a unique perspective when gathering research on sports since they are able to more closely look at and understand the female fan side of sporting events.[68]

Following feminist or other reflexive and tradition-breaking paradigms, sports are sometimes studied as contested activities, i.e. as activities in the center of various people/groups interests (connection of sports and gender, mass media, or state-politics). These perspectives provide people with different ways to think about sports and figure out the differences between the binary divisions. Sports have always been of tremendous impact to the world as a whole, as well as individual societies and the people within them. There are so many positive aspects to the world of sport, specifically, organized sport. Sports involve community values, attempting to establish and exercise good morals and ethics. Spectator sports provide watchers with an enlivenment through key societal values displayed in the "game". Becoming a fan teaches you a large variety of skills as well that are a very important part of everyday life in the office, at home, and on the go. Some of these skills include teamwork, leadership, creativity, and individuality.[citation needed]

See also

- History of sport

- Women's sport

- Anti-jock Movement

- Physical cultural studies

- Harry Edwards

- Physical culture

- Fitness culture

- Sports strategy

- Sociology of the body

- The Outsourced Self

- Quantified self

- Exercise trends

References

- ^ Macri, Kenneth. "Not Just a Game: Sport and Society in the United States". inquiriesjournal.com. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- ISBN 978-0873222358.

- ^ "About NASSS". nasss.org. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Archetti, Eduardo P. “The Meaning of Sport in Anthropology: A View from Latin America.” Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y Del Caribe / European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, no. 65 (1998): 91–103. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25675799.

- ^ ISBN 9780199858910.

- JSTOR 43606920. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ISBN 9780801838309.

- ISBN 9780395822920.

- ISBN 9780765804402.

- ISBN 978-0-745-66993-9.

- ^ Lapchick, Richard B. (1991). Five Minutes to Midnight: Race and Sport in the 1990s. Seattle: Madison Books. p. 290.

- ^ Captain, Gwendolyn; Vertinsky, Patricia (September 1998). "More Myth than History: American Culture and Representations of the Black Female's Athletic Ability". Journal of Sport History. 25 (3): 552–553. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-333-64231-3.

- ISBN 1850009171.

- S2CID 144844174.

- S2CID 145292818. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ISBN 9780231069571.

- S2CID 144357744. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- OCLC 652430995.

- ISBN 9780511803109.

- S2CID 194009566. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Robertson, Roland (1970). The Sociological Interpretation of Religion. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 50–51.

- ISBN 9780029211304.

- ISBN 9781412810067.

- JSTOR 2578440. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Giulianotti, Richard (2015). Sport: A Critical Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 35.

- S2CID 144798843. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ISBN 0231073070.

- ISBN 9780520035003.

- ISBN 9780231133418.

- ^ Giulianotti, Richard (2015). Sport: A Critical Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 42–43.

- ISBN 074530303X.

- ^ Adorno, Theodor W. (2001). The Culture Industry. London: Routledge.

- ISBN 9780855145019.

- ISBN 9780807842201.

- ISBN 9780822311980.

- ISBN 9789513900144.

- S2CID 55615322. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- JSTOR 43609130. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ISBN 9780415070287.

- ISBN 9780870233876.

- ^ Miliband, Ralph (1977). Marxism and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 52–53.

- ^ Williams, Raymond (1977). Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 110–111.

- ^ Clarke, J.; Critcher, C. (1985). The Devil Makes Work: Leisure in Capitalist Britain. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 228.

- ISBN 9780415070287.

- ISBN 9780231100427.

- ISBN 9780521572170.

- ^ Rinehart, Robert E.; Sydnor, Synthia (1996). To the Extreme. New York: State University of New York Press. p. 136.

- ISBN 9780415078764.

- S2CID 55355645. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Foucault, Michel (1980). Power/Knowledge. Brighton: Harvester Press.

- ISBN 9780714634890.

- S2CID 144819775. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Segel, Harold B. (1998). Body Ascendant: Modernism and the Physical Imperative. Baltimore & London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Hoberman, John M. (1984). Sport and Political Ideology. Austin: U. of Texas Press. pp. 244–245.

- S2CID 144506344. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- S2CID 144030276. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- S2CID 145591779. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ISBN 9780807041055.

- ISBN 9781446223420.

- ^ Giulianotti, Richard (2008). Sport kritička sociologija. Beograd: Clio. pp. 172–173.

- S2CID 146277415. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- S2CID 143774370. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ISBN 9780446676823.

- ^ "Sports Emotions - Sports Psychology - IResearchNet". Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- ^ "Sports - Sociology of sports". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- .

- S2CID 144986873.

Further reading

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1993). How can one be a sports fan?. London: Routledge In The Cultural Studies Reader, During, S. (ed.). pp. 339–355. OCLC 28818343.

- Cashmore, Ernest (2000). Sports Culture: An A-Z Guide. London, UK; New York, NY: Routledge. OCLC 41548336.

- Coakley, Jay J. (2004). Sport in Society: Issues and Controversies (8th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. OCLC 51631598.

- Collins, Michael F. and Tess Kay (2003). Sport and Social Exclusion. London: Routledge. OCLC 51527713. - Examines how social factors that exclude participation in sports, including poverty, age, ethnicity, gender, etc.

- Danielson, Michael N. (1997). Home Team: Professional Sports and the American Metropolis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. OCLC 35397761.

- Dunning, Eric; Malcolm, Dominic (2003). Sport: Critical Concepts in Sociology. London, UK; New York, NY: Routledge. OCLC 51222256.

- Dyck, Noel (2000). Games, Sports and Cultures. Oxford: Berg. OCLC 44485325.

- Dunleavy, Aidan O.; Andrew W. Miracle & C. Roger Rees (1982). Studies in the Sociology of Sport. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press. OCLC 8762539.

- Eitzen, D. Stanley and George Harvey Sage (2003). Sociology of North American Sport (7th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. OCLC 49276709.

- Giulianotti, Richard (2005). Sport: A Critical Sociology. Oxford, UK; Malden, MA: Polity. OCLC 56659449.

- Giulianotti, Richard (2004). Sport and Modern Social Theorists. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. OCLC 55095622.

- Guttmann, Allen (2004). From Ritual to Record: The Nature of Modern Sports (Updated with a new afterword ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. OCLC 54503875.

- Guttmann, Allen (1994). Games and Empires. Modern Sports and Cultural Imperialism. New York: Columbia University Press. OCLC 30036883.

- Heywood, Leslie, and Shari L. Dworkin (2003). Built to Win: The Female Athlete as Cultural Icon. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. )

- Houlihan, Barrie, ed. (2003). Sport and Society: A Student Introduction. London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. OCLC 52460691.

- Jarvie, Grant & Maguire, Joseph (1994). Sport and Leisure in Social Thought. London: Routledge. OCLC 30030487.

- Jarvie, Grant (2006). Sport, Culture and Society. An Introduction. London: Routledge. OCLC 60650865.

- Jay, Kathryn (2004). More than just a Game: Sports in American Life since 1945. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. OCLC 54503879.

- Johnson, Jay and Margery Jean Holman (2004). Making the Team: Inside the World of Sport Initiations and Hazing. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Scholars' Press. OCLC 55973445.

- Jones, Robyn L.; Armour, Kathleen M. (2000). Sociology of Sport: Theory and Practice. Harlow, Essex, England: Longman. OCLC 46486583.

- Laker, Anthony (2002). The Sociology of Sport and Physical Education: An Introductory Reader. London, UK; New York, NY: RoutledgeFalmer. OCLC 46732587.

- Lenskyj, Helen Jefferson (2003). Out on the Field: Gender, Sport and Sexualities. Toronto: Women's Press. ISBN 9780889614161.

- Loland, Sigmund; Skirstad, Berit; Waddington, Ivan (2006). Pain and Injury in Sport: Social and Ethical Analysis. London, UK; New York, NY: Routledge. OCLC 60453764.

- Maguire, Joseph A. (2002). Sport Worlds: A Sociological Perspective. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. OCLC 48162875.

- Joseph A. Maguire; Kevin Young, eds. (2002). Theory, Sport & Society. Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Boston, MA: JAI. OCLC 48837757.

- Nixon, Howard L. (2008). Sport in a Changing World. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers. OCLC 181368766.

- Scambler, Graham (2005). Sport and Society: History, Power and Culture. Maidenhead, England; New York, NY: Open University Press. OCLC 58554471.

- Scraton, Sheila and Anne Flintoff (2002). Gender and Sport: A Reader. London, UK; New York, NY: Routledge. OCLC 47255389.

- Sugden, John Peter and Alan Tomlinson (2002). Power Games: A Critical Sociology of Sport. London, England; New York, NY: Routledge. OCLC 50291216.

- Tomlinson, Alan (2005). Sport and Leisure Cultures. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. OCLC 57000964.

- Tomlinson, Alan and Christopher Young (2006). National Identity and Global Sports Events: Culture, Politics, and Spectacle in the Olympics and the Football World Cup. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. OCLC 57349033.

- Waddington, Ivan (2000). Sport, Health and Drugs: A Critical Sociological Perspective. London, UK; New York, NY: E & FN Spon. OCLC 42692125.

- Woods, Ron B. (2007). Social Issues in Sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. OCLC 70673116.

- Yiannakis, Andrew and Merrill J. Melnick (2001). Contemporary Issues in Sociology of Sport (Revised ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. OCLC 45207842.

- Young, Kevin and Kevin B. Wamsley (2005). Global Olympics: Historical and Sociological Studies of the Modern Games. Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Oxford, UK: Elsevier JAI. OCLC 62133166.

- Young, Kevin and Philip White (2007). Sport and Gender in Canada (2nd ed.). Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press. OCLC 70062619.