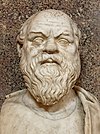

Socratic problem

| Part of a series on |

| Socrates |

|---|

|

| Eponymous concepts |

|

| Pupils |

| Related topics |

|

|

In historical scholarship, the Socratic problem (also called Socratic question)[1] concerns attempts at reconstructing a historical and philosophical image of Socrates based on the variable, and sometimes contradictory, nature of the existing sources on his life. Scholars rely upon extant sources, such as those of contemporaries like Aristophanes or disciples of Socrates like Plato and Xenophon, for knowing anything about Socrates. However, these sources contain contradictory details of his life, words, and beliefs when taken together. This complicates the attempts at reconstructing the beliefs and philosophical views held by the historical Socrates. It has become apparent to scholarship that this problem is seemingly impossible to clarify and thus perhaps now classified as unsolvable.[2][3] Early proposed solutions to the matter still pose significant problems today.[4]

Socrates was the main character in most of

There are also four sources extant in fragmentary states:

philosophers.Xenophon

There are four works of

Plato

Socrates—who is often credited with turning Western philosophy in a more ethical and political direction and who was put to death by the democracy of Athens in May 399 BC—was Plato's mentor. Plato, like some of his contemporaries, wrote dialogues about his teacher. Much of what is known about Socrates comes from Plato's writings; however, it is widely believed that very few, if any, of Plato's dialogues can be verbatim accounts of conversations between them or unmediated representations of Socrates' thought. Many of the dialogues seem to use Socrates as a device for Plato's thought, and inconsistencies occasionally crop up between Plato and the other accounts of Socrates; for instance, Plato has Socrates denying that he would ever accept money for teaching, while Xenophon's Symposium clearly has Socrates stating that students pay him to teach wisdom and that this is what he does for a living.

Aristotle

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2022) |

Others

Aeschines

Two relevant works pertain to periods in Socrates' life, of which Aeschines could not have had any personal first-hand experiential knowledge. However, substantial amounts are extant of his works Alcibiades and Aspasia.[23]

Antisthenes

Antisthenes was a pupil of Socrates, and was known to accompany him.[24]

Issues relating to the sources

Aristophanes (c. 450–386 BCE) was alive during the early years of Socrates. One source shows Plato and Xenophon were about 45 years younger than Socrates,[25] other sources show Plato as something in the range of 42–43 years younger, while Xenophon is thought to be 40 years younger.[26][27][28][29]

Issues resulting from translation

Apart from the existing identified issue of conflicting elements present in accounts and writings, there is the additional inherent concern of the veracity of transfer of meaning by translation from

History of the problem

Efforts have been made by writers for centuries to address the problem. According to one scholar (Patzer) the number of works with any significance in this issue, prior to the nineteenth century, are few indeed.

An essay written by Friedrich Schleiermacher in 1815 ("The Worth of Socrates as a Philosopher"), published 1818 (English translation 1833) is considered the most significant and influential toward developing an understanding of the problem.[33][34]

Throughout the 20th century, two strains of interpretation arose: the literary contextualists, who tended to interpret Socratic dialogues based on literary criticism, and the analysts, who focus much more heavily on the actual arguments contained within the different texts.[35]

Early in the 21st century, most of the scholars concerned have settled to agreement instead of argument about the nature of the significance of ancient textual sources in relation to this problem.[36]

Manuscript tradition

A fragment of Plato's Republic (588b-589b) was found in Codex VI, of the Nag Hammadi discoveries of 1945.[37][38]

Plato primary edition

The Latin language corpus was by

Xenophon primary edition

The Memorabilia appeared in the Florence Junta in 1516.[41][42]

The first Apology was by Johan Reuchlin in 1520.[43]

Scholarly analysis

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2015) |

Karl Popper, who considered himself to be a disciple of Socrates, wrote about the Socratic problem in his book The Open Society and Its Enemies.[44]

Søren Kierkegaard addressed the Socratic problem in Theses II, III and VII of his On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates.[45][46]

The German classical scholar Friedrich Schleiermacher addressed the "Socratic problem" in his essay "The Worth of Socrates as a Philosopher".[47] Schleiermacher maintained that the two dialogues Apology and Crito are purely Socratic. They were, therefore, accurate historical portrayals of the real man, and hence history and not Platonic philosophy at all. All of the other dialogues that Schleiermacher accepted as genuine he considered to be integrally bound together and consistent in their Platonism. Their consistency is related to the three phases of Plato's development:

- Foundation works, culminating in Parmenides;

- Transitional works, culminating in two so-called families of dialogues, the first consisting of Sophist, Statesman and Symposium, and the second of Phaedo and Philebus; and finally

- Constructive works: Republic, Timaeus and Laws.

Schleiermacher's views on the chronology of Plato's work are rather controversial. In Schleiermacher's view, the character of Socrates evolves over time into the "Stranger" in Plato's work, and fulfills a critical function in Plato's development, as he appears in the first family above as the "Eleatic Stranger" in Sophist and Statesman, and as the "Mantitenean Stranger" in the Symposium. The "Athenian Stranger" is the main character of Plato's Laws. Further, the Sophist–Statesman–Philosopher family makes particularly good sense in this order, as Schleiermacher also maintains that the two dialogues, Symposium and Phaedo, show Socrates as the quintessential philosopher in life (guided by Diotima) and into death, the realm of otherness. Thus the triad announced both in the Sophist and in the Statesman is completed, though the Philosopher, being divided dialectically into a "Stranger" portion and a "Socrates" portion, isn't called "The Philosopher"; this philosophical crux is left to the reader to determine. Schleiermacher thus takes the position that the real Socratic problem is understanding the dialectic between the figures of the "Stranger" and "Socrates".

Proposed solutions

Four solutions elucidated by Nails were proposed early in the history of the Socratic problem and are still relevant, even though each still poses problems today:[4]

- Socrates is the individual whose qualities exhibited in Plato’s writings are corroborated by Aristophanes and Xenophon.

- Socrates is he who claims “to possess no wisdom” but still participates in exercises with the aim of gaining understanding.

- Socrates is the [individual named] Socrates who appears in Plato’s earliest dialogues.

- The real Socrates is the one who turns from a pre-Socratic interest in nature to ethics, instead.

References

- ^ A Rubel, M Vickers, Fear and Loathing in Ancient Athens: Religion and Politics During the Peloponnesian War, Routledge, 2014, p. 147.

- ^ Prior, W. J., "The Socratic Problem" in Benson, H. H. (ed.), A Companion to Plato (Blackwell Publishing, 2006), pp. 25–35.

- ISBN 9780511780257. Online Publication Date: March 2011 , Print Publication Year: 2010. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ a b Nails, Debra (Spring 2014). "Early attempts to solve the Socratic problem". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Supplement to ‘Socrates’. Stanford University.

- ^ J Ambury. Socrates (469–399 B.C.E.) Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy [Retrieved 2015-04-19]

- ^ May, H. (2000). On Socrates. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. p. 20.

- ^ catalogue of Harvard University Press – Xenophon Volume IV [Retrieved 2015-3-26]

- ISBN 0521648300[Retrieved 2015-04-19]

- ^ Aristophanes, W.C. Green - commentary on The Clouds (p.6) Catena classicorum Rivingtons, 1868 [Retrieved 2015-04-20]

- ISBN 978-1405192606. Retrieved 2015-04-17. (a translation of one fragment reads "But from them the sculptor, blatherer on the lawful, turned away. Spellbinder of the Greeks, who made them precise in language. Sneerer trained by rhetoricians, sub-Attic ironist." Cf. source for a discussion of this quote.

- ^ )

- ^ ISBN 978-0801472985. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ M MacLaren - Xenophon. Banquet; Apologie de Socrate by Francois Ollier The American Journal of Philology Vol. 85, No. 2 (Apr., 1964), pp. 212-214 (Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press in JSTOR) [Retrieved 2015-04-20]

- ISBN 9781405192606. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ISBN 1137325925[Retrieved 2015-04-17]

- ISBN 9781847144416. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ Krämer (1990) ascribes this view to Eduard Zeller (Hans Joachim Krämer, Plato and the Foundations of Metaphysics, SUNY Press, 1990, pp. 93–4).

- ^ Penner, T. "Socrates and the early dialogues" in Kraut, R. (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Plato (Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 121. See also Irwin, T. H., "The Platonic Corpus" in Fine, G. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Plato (Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 77–85.

- ^ Rowe, C. "Interpreting Plato" in Benson, H. H. (ed.), A Companion to Plato (Blackwell Publishing, 2006), pp. 13–24.

- ISBN 9780195119800.

- ISBN 978-0521648301.

- ISBN 978-0199769193.

- ISBN 0801499038[Retrieved 2015-04-20]

- ^ J Piering - Antisthenes Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy[Retrieved 2015-04-20]

- ^ Nails, D. (Spring 2014). "Socrates". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. section 2:1, paragraph 2. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Meinwald, C.C. "Plato". The Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Kraut, R. "Socrates". The Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Tuplin, C.J. "Xenophon". The Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ISBN 978-1136783944. Retrieved 24 March 2015 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 0801472989. Retrieved 17 April 2015 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 1441112847[Retrieved 2015-04-17]

- ^ ISBN 9780792335436. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ISBN 9780521833424. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ^ M Trapp - Introduction: Questions of Socrates [Retrieved 3 May 2015] (p.xvi)

- ^ Nails, Debra (February 8, 2018). "Socrates". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0199695423. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ISBN 0567178269 [Retrieved 2015-04-20] (primary source for Nag Hammadi was this)

- ISBN 0802837859[Retrieved 2015-04-20]

- ISBN 9004087877. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ Dibdin, T. Frognall (1804). [no title cited]. W. Dwyer. p. 5. (located Ficinus using this source, which though provides suggestions of the wrong years for publication - p. 5)

- ISBN 9004111751. Retrieved 20 April 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ Marsh, David. "Xenophon" (PDF). Catalogus Translationum et Commentariorum. 7: 82. Retrieved 25 August 2015. (editio princeps using Brown, V. "Catalogus Translationum" (PDF).

Cicero translated Oeconomicus

) - ^ Schmoll, E.A. (1990). "The manuscript tradition of Xenophon's Apologia Socratis". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 31 (1). Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ISBN 0521890551[reference Retrieved 2015-04-20, material added at a prior date]

- ISBN 0865547424Volume 2 of International Kierkegaard commentary [Retrieved 2015-04-20] (mentions Thesis VII)

- ISBN 1400846927[Retrieved 2015-04-20] (shows details of Theses II, III & VII)

- ^ The Philological museum, Volume 2 (edited by J.C. Hare) Printed by J. Smith for Deightons, 1833 [Retrieved 2015-05-03] (sourced firstly at L-A Dorion in D.R. Morrison - The Cambridge Companion to Socrates)

Further reading

- Popper, Karl (2002). The Open Society and Its Enemies. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-29063-0.

- Schleiermacher, Friedrich (1973). Introductions to the Dialogues of Plato. Ayer Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-0-405-04868-5.

- Schleiermacher, Friedrich (1996). Ueber die Philosophie Platons. Philos. Bibliotek. Band 486, Meiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7873-1462-1.