Soumaoro Kanté

| Part of a series on |

| Traditional African religions |

|---|

|

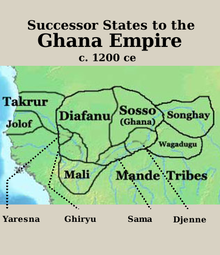

Soumaoro Kanté (also known as Sumaworo Kanté or Sumanguru Kanté) was a 13th-century king of the

Whether or not any of the deeds attributed to him actually happened as such, or even whether Kante existed at all, is debated by historians. Traditional oral histories provide a wide variety of information, some of which is contradictory and much that is obviously mythical.[3][4]

Biography

Soumaoro Kanté is portrayed as a villainous sorcerer-king in the national epic of Mali, the

Soumaoro is viewed as one of the true champions of Traditional African religion due to his reputation in the epic as someone possessing extraordinary magical powers. According to Fyle, Soumaoro was the inventor of the balafon and the dan (a four-string guitar used by the hunters and griots).[6]

As evidence of his supernatural powers, the griot Lansine Diabate notes, "At that time, owing to his magical powers, every fly which rested on the balafon of Soso [the royal musician], Sumaworo was able to find it out from a cloud of flies to kill it."[7] Diabate goes on to say that it was when the balafon player first refused to play for the king that Soumaoro Kanté's demise was anticipated.[7]

Notes

- ISBN 006270012X

- ^ Stride, G. T & Ifeka, Caroline, Peoples and empires of West Africa: West Africa in history, 1000–1800, Africana Pub. Corp., 1971, p 49

- ^ Conrad, David C. “Oral Sources on Links between Great States: Sumanguru, Servile Lineage, the Jariso, and Kaniaga.” History in Africa, vol. 11, 1984, pp. 35–55. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3171626. Accessed 22 Sept. 2023.

- ^ Jansen, Jan. “Beyond the Mali Empire—A New Paradigm for the Sunjata Epic.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 51, no. 2, 2018, pp. 317–40. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/45176442. Accessed 22 Sept. 2023.

- ^ Editor: Senghor, Léopold Sédar, Éthiopiques, Issues 21-24, Grande imprimerie africaine, 1980, p 79

- ISBN 9780761814566 [1]

- ^ OCLC 1051687994.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link

Bibliography

- Davidson, Basil. Africa in History. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

- Charry, Eric. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago: Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology, 2000.

- Carruth, Gorton, The encyclopedia of world facts and dates, p 167, 1192 HarperCollins Publishers, 1993, ISBN 006270012X

- Stride, G. T & Ifeka, Caroline, Peoples and empires of West Africa: West Africa in history, 1000–1800, p 49, Africana Pub. Corp., 1971

- (in French) Editor: Senghor, Léopold Sédar, Éthiopiques, Issues 21-24, Grande imprimerie africaine, 1980, p 79

- Fyle, Magbaily, Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa, ISBN 9780761814566 [2]

External links

- Sundiata and Mansa Musa on the Web web directory