Ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

| Part of a series on |

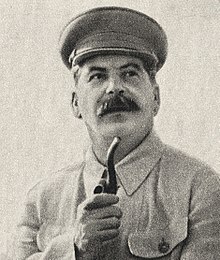

| Stalinism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Leninism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

Before the

Marxism–Leninism

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism–Leninism |

|---|

|

Marxism–Leninism was the ideological basis for the Soviet Union.

Despite having evolved over the years, Marxism–Leninism had several central tenets.

Leninism

In

Lenin, in light of the

Stalinism

Stalinism, while not an ideology

We stand for the strengthening of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which represents the mightiest and most powerful authority of all forms of State that have ever existed. The highest development of the State power for the withering away of State power —this is the Marxian formula. Is this "contradictory"? Yes, it is "contradictory." But this contradiction springs from life itself and reflects completely Marxist dialectic.[12]

The idea that the state would wither away was later abandoned by Stalin at the

De-Stalinization

After Stalin died and once the ensuing power struggle subsided, a period of

Concepts

Dictatorship of the proletariat

Either the dictatorship of the landowners and capitalists, or the dictatorship of the proletariat [...] There is no middle course [...] There is no middle course anywhere in the world, nor can there be.

—Lenin, claiming that people had only two choices; a choice between two different, but distinct class dictatorships.[15]

Lenin, according to his interpretation of

Marx, similar to Lenin, considered it fundamentally irrelevant whether a bourgeois state was ruled according to a

It was in the period of 1920–1921 that Soviet leaders and ideologists began differentiating between socialism and communism; hitherto the two terms had been used to describe similar conditions.[23] From then, the two terms developed separate meanings. According to Soviet ideology, Russia was in the transition from capitalism to socialism (referred to interchangeably under Lenin as the dictatorship of the proletariat), socialism being the intermediate stage to communism, with the latter being the final stage which follows after socialism.[23] By now, the party leaders believed that universal mass participation and true democracy could only take form in the last stage, if only because of Russia's current conditions at the time.[23]

[Because] the proletariat is still so divided, so degraded, so corrupted in parts [...] that an organization taking in the whole proletariat cannot directly exercise proletarian dictatorship. It can be exercised only by a vanguard that has absorbed the revolutionary energy of the class.

— Lenin, explaining the increasingly dictatorial nature of the regime.[24]

In early Bolshevik discourse, the term "dictatorship of the proletariat" was of little significance; the few times it was mentioned, it was likened to the form of government which had existed in the Paris Commune.[23] With the ensuing Russian Civil War and the social and material devastation that followed, however, its meaning was transformed from communal democracy to disciplined totalitarian rule.[25] By now, Lenin had concluded that only a proletarian regime as oppressive as its opponents could survive in this world.[26] The powers previously bestowed upon the soviets were now given to the Council of People's Commissars; the central government was in turn to be governed by "an army of steeled revolutionary Communists [by Communists he referred to the Party]".[24] In a letter to Gavril Myasnikov, Lenin in late 1920 explained his new reinterpretation of the term "dictatorship of the proletariat";[27]

Dictatorship means nothing more nor less than authority untrammelled by any laws, absolutely unrestricted by any rules whatever, and based directly on force. The term 'dictatorship' has no other meaning but this.[27]

Lenin justified these policies by claiming that all states were class states by nature, and that these states were maintained through

Consequently, "bourgeoisie" became synonymous with "opponent" and with people who disagreed with the party in general.[29] These oppressive measures led to another reinterpretation of the dictatorship of the proletariat and socialism in general; it was now defined as a purely economic system.[30] Slogans and theoretical works about democratic mass participation and collective decision-making were now replaced with texts which supported authoritarian management.[30] Considering the situation, the party believed it had to use the same powers as the bourgeoisie to transform Russia, for there was no other alternative.[31] Lenin began arguing that the proletariat, similar to the bourgeoisie, did not have a single preference for a form of government, and because of that dictatorship was acceptable to both the party and the proletariat.[32] In a meeting with party officials, Lenin stated—in line with his economist view of socialism—that "[i]ndustry is indispensable, democracy is not", further arguing that "we do not promise any democracy or any freedom".[32]

Anti-imperialism

Imperialism is capitalism at a stage of development at which the dominance of monopolies and finance-capital is established; in which the export of capital has acquired pronounced importance; in which the division of the world among the international trusts has begun; in which the divisions of all territories of the globe among the biggest capitalist powers has been completed.

—Lenin, citing the main features of capitalism in the age of imperialism in Imperialism: the Highest Stage of Capitalism.[33]

The Marxist theory on imperialism was conceived by Lenin in his book,

Lenin did not know when the imperialist stage of capitalism began, and claimed it would be foolish to look for a specific year, however he did assert it began at the beginning of the 20th century (at least in Europe).[33] Lenin believed that the economic crisis of 1900 accelerated and intensified the concentration of industry and banking, which led to the transformation of the finance capital connection to industry into the monopoly of large banks."[36] In Imperialism: the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin wrote; "the twentieth century marks the turning-point from the old capitalism to the new, from the domination of capital in general to the domination of finance capital."[36] Lenin's defines imperialism as the monopoly stage of capitalism.[37]

Despite radical anti-imperialism being an original core value of Bolshevism, the Soviet Union from 1939 onward was widely viewed as a de facto imperial power whose ideology could not allow it to admit its own imperialism. Through the Soviet ideological viewpoint, pro-Soviet factions in each country were the only legitimate voice of "the people" regardless of whether they were minority factions. All other factions were simply class enemies of "the people", inherently illegitimate rulers regardless of whether they were majority factions. Thus, in this view, any country that became Soviet or a Soviet ally naturally did so via a legitimate voluntary desire, even if the requesters needed Soviet help to accomplish it. The principal examples were the Soviet invasion of Finland yielding the annexation of Finnish parts of Karelia, the Soviet invasion of Poland, the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states, and the postwar de facto dominance over the satellite states of the Eastern Bloc under a pretense of total independence. In the post-Soviet era even many Ukrainians, Georgians, and Armenians feel that their countries were forcibly annexed by the Bolsheviks, but this has been a problematic view because the pro-Soviet factions in these societies were once sizable as well. Each faction felt that the other did not represent the true national interest. This civil war–like paradox has been seen in the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, as pro-Russian Crimeans have been viewed as illegitimate by pro-Ukrainian Crimeans, and vice versa.

Peaceful coexistence

The loss by imperialism of its dominating role in world affairs and the utmost expansion of the sphere in which the laws of socialist foreign policy operate are a distinctive feature of the present stage of social development. The main direction of this development is toward even greater changes in the correlation of forces in the world arena in favour of socialism."

—Nikolay Inozemtsev, a Soviet foreign policy analyst, referring to series of events (which he believed) would lead to the ultimate victory of socialism.[38]

"Peaceful coexistence" was an ideological concept introduced under Khrushchev's rule.[39] While the concept has been interpreted by fellow communists as proposing an end to the conflict between the systems of capitalism and socialism, Khrushchev saw it instead as a continuation of the conflict in every area with the exception in the military field.[40] The concept claimed that the two systems were developed "by way of diametrically opposed laws", which led to "opposite principles in foreign policy."[38]

The concept was steeped in Leninist and Stalinist thought.

The emphasise on peaceful coexistence did not mean that the Soviet Union accepted a static world, with clear lines.[38] They continued to upheld the creed that socialism was inevitable, and they sincerely believed that the world had reached a stage in which the "correlations of forces" were moving towards socialism.[38] Also, with the establishment of socialist regimes in Eastern Europe and Asia, Soviet foreign policy-planners believed that capitalism had lost its dominance as an economic system.[38]

Socialism in one country

The concept of "socialism in one country" was conceived by Stalin in his struggle against

In late 1925, Stalin received a letter from a party official which stated that his position of "Socialism in One Country" was in contradiction with

See also

- Bolshevism

- Brezhnev Doctrine

- Ideology of the Chinese Communist Party

- Ideology of the Workers' Party of Korea

- Ho Chi Minh Thought

- Kadarism

- Politics of Fidel Castro

- Ceaușism

- Real socialism

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e Sakwa 1990, p. 206.

- ^ a b Sakwa 1990, p. 212.

- ^ a b c Smith 1991, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Smith 1991, p. 82.

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 83.

- ^ Sakwa 1990, pp. 206–212.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Smith 1991, p. 76.

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 77.

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 767.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith 1991, p. 78.

- ^ Smith 1991, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith 1991, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d van Ree 2003, p. 133.

- ^ Volkogonov 1999, Introduction.

- ^ a b c Harding 1996, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Lenin, Vladimir (1918). "Class Society and the State". The State and Revolution. Vol. 25 (Collected Works). Marxists Internet Archive (published 1999). Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Harding 1996, p. 155.

- ^ Harding 1996, p. 156.

- ^ Harding 1996, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Harding 1996, pp. 157–158.

- ^ a b c Harding 1996, p. 158.

- ^ Harding 1996, pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b c d e Harding 1996, p. 159.

- ^ a b Harding 1996, p. 161.

- ^ Harding 1996, p. 160.

- ^ Harding 1996, pp. 160–161.

- ^ a b c d e Harding 1996, p. 162.

- ^ Harding 1996, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Harding 1996, p. 163.

- ^ a b Harding 1996, p. 165.

- ^ Harding 1996, pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b Harding 1996, p. 166.

- ^ a b McDonough 1995, p. 352.

- ^ a b c McDonough 1995, p. 339.

- ^ a b c d e McDonough 1995, pp. 344–347.

- ^ a b McDonough 1995, p. 353.

- ^ McDonough 1995, p. 354.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Evans 1993, p. 72.

- ^ Evans 1993, p. 71.

- ^ Evans 1993, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b van Ree 2003, p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f van Ree 2003, p. 127.

- ^ a b c van Ree 2003, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d e van Ree 2003, p. 129.

- ^ van Ree 2003, pp. 129–130.

- ^ van Ree 2003, p. 130.

- ^ van Ree 2003, pp. 134–135.

Bibliography

Articles and journal entries

- McDonough, Terrence (1995). "Lenin, Imperialism, and the Stages of Capitalist Development". JSTOR 40403507.

Books

- ISBN 9789811063664.

- ISBN 978-0192880529.

- Eaton, Katherine Bliss (2004). Daily Life in the Soviet Union. ISBN 978-0313316289.

- Eisen, Jonathan (1990). The Glasnost Reader. ISBN 978-0453006958.

- Evans, Alfred (1993). Soviet Marxism–Leninism: The Decline of an Ideology. ISBN 978-0275947637.

- ISBN 978-0674410305.

- Gill, Graeme (2002). The Origins of the Stalinist Political System. ISBN 978-0674410305.

- Harding, Neil (1996). Leninism. ISBN 978-0333664827.

- Harris, Jonathan (2005). Subverting the System: Gorbachev's Reform of the Party's Apparat 1986–1991. ISBN 978-0742526785.

- Kenez, Peter (1985). The Birth of the Propaganda State: Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization, 1917–1929. ISBN 978-0521313988.

- Lenoe, Matthew Edward (2004). Closer to the Masses: Stalinist Culture, Social Revolution, and Soviet Newspapers. ISBN 978-0674013193.

- Lowenhardt, John; van Ree, Erik; Ozinga, James (1992). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Politburo. ISBN 978-0312047849.

- Matthews, Marvyn (1983). Education in the Soviet Union: Policies and Institutions since Stalin. ISBN 978-0043701140.

- ISBN 978-0415005067.

- ISBN 978-0415071536.

- Smith, Gordon (1988). Soviet Politics: Continuity and Contradictions. ISBN 978-0312007959.

- Smith, Gordon (1991). Soviet Politics: Continuity and Contradictions (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-0333535769.

- Swain, Geoff (2006). Trotsky. ISBN 978-0582771901.

- van Ree, Erik (2003). The Political Thought of Joseph Stalin: A Study in Twentieth Century Revolutionary Patriotism. ISBN 978-1-135-78604-5.

- Volkogonov, Dmitri (1999). Autopsy for an Empire : The Seven Leaders Who Built the Soviet Regime. Free Press. ISBN 978-0684834207.

- Williams, Simons (1984). The Party Statutes of the Communist World. ISBN 978-9024729753.

- Zimmerman, William (1977). Dallin, Alexander (ed.). The Twenty-fifth Congress of the CPSU: Assessment and Context. ISBN 978-0817968434.