Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919

| Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russian Civil War, Polish–Soviet War, Estonian War of Independence, Latvian War of Independence, Lithuanian Wars of Independence, and Ukrainian War of Independence | |||||||||

Soviet anti-Polish propaganda poster 1920 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Swedish volunteers[1] |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

Dmitry Nadyozhny | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Total: unknown, 70,000+ Estonia: 19,000[3] Poland: ~50,000 | 285,000 | ||||||||

The Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919 was part of the campaign by

The campaign eventually became bogged down, leading to the Estonian

Soviet war aims

The newly-formed

Background

After signing the

In November and December, the German army started a retreat westwards. Demoralised officers and mutinous soldiers abandoned their garrisons en masse and returned home. The areas abandoned by the

The Bolsheviks were also implementing a new strategy, "Revolution from abroad" (Revolutsiya izvne—literally, "revolution from the outside"), based on an assumption that revolutionary masses desire revolution but are unable to carry it out without help from more organized and advanced Bolsheviks. Hence, as

-

Territories occupied by Germany during 1918

-

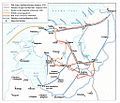

Estonian and Soviet operations in Estonia and Latvia, 1918–19

-

Soviet operations in Southeast Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Belorussia in 1918–19

-

Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian and Polish counterattacks

-

Polish-Ukrainian front and Polish-Soviet front as forming in February 1919

Offensives

Estonian direction

The

Subsequently, the northeastern front stabilized along the

Byelorussian direction

The

On January 12 Soviet High Command ordered deep scouting towards the

It is speculated that among the aims of the Bolsheviks one goal was to drive through eastern and central Europe and support the

Finally, the first Polish-Soviet clashes happened in mid-February, in the area of the towns of Bereza Kartuska and Mosty, where both armies clashed in a series of skirmishes. [11] The Soviet offensive came to a halt by late February and it became apparent that a new line had estalished itself between the Polish and Soviet forces. Both the Soviet offensive and the Polish counterattack started at the same time, which resulted in an increasing number of troops being brought to the area.

Romanian direction

In early 1918, Bessarabia, a former Russian province,

Aftermath

The Baltic and Romanian Armies proved to be far more capable opponents than the Red Army had assumed. The Pskov Offensive of the Estonian Army's Petseri Battle Group captured Pskov on 25 May 1919, destroyed the Estonian Red Riflemen units in the process, and expelled all other Soviet forces from the territory between Estonia and the

In the wake of the Soviet drive west as well as the Polish advance east through Byelorussia, a new line had formed between the newly created Soviet Socialist Republic of Byelorussia and the Republic of Poland. Armies from both sides regularly engaged in local clashes despite the yet peaceful relations between Poland and the Soviets. Such clashes marked a prelude to the Polish-Soviet War which began in April of the same year with the Polish Vilna Offensive.[13]

Historiography

A comprehensive historical analysis of the campaign against Poland was performed by

Norman Davies in his book claims that "Target Vistula" ("Цель – Висла" or similar) was the Soviet codename of the offensive. This term, however, is mostly absent in Polish and

References

- ^ Per Finsted. "Boganmeldelse: For Dannebrogs Ære - Danske frivillige i Estlands og Letlands frihedskamp 1919 af Niels Jensen". chakoten.dk (in Danish). Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ^ Thomas & Boltowsky (2019), p. 23.

- OCLC 250435918. Archived from the originalon August 22, 2010.

- ISBN 83-7001-914-5.

- ^ Pilsudski 1972.

- ^ a b Jyri Kork, ed. (1988) [1938]. Estonian War of Independence 1918–1920. Baltimore: Esto.

Reprint from Historical Committee for the War of Independence, Tallinn

- ^ Davies 2003, p. 12.

- ^ Davies 2003, p. 39.

- ^ Davies 2003, p. 29.

- ^ Davies 2003, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Neiberg & Jordan 2008, p. 215.

- ISBN 9781857431377.

- ^ Davies 2003, p. 48 – 54.

- ISBN 83-85719-68-7. Archived from the original on June 28, 2006.. THE SUMMIT TIMES (in Polish)..

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) or Andrzej Leszek Szczesniak. "Wojna polsko-bolszewicka 1918–1920"

Bibliography

- ISBN 0-7126-0694-7.

- Pilsudski, Jozef (1972). Year 1920 and its climax Battle of Warsaw during the Polish Soviet war 1919-1920.

- Neiberg, M.S.; Jordan, D. (2008). The Eastern Front 1914-1920. ISBN 978-1-906626-00-6.

- Thomas, Nigel; Boltowsky, Toomas (2019). Armies of the Baltic Independence Wars 1918–20. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472830791.