Sperm

Sperm (pl.: sperm or sperms) is the

Sperm cells form during the process known as

Sperm cells cannot divide and have a limited lifespan, but after fusion with

The word sperm is derived from the Greek word σπέρμα, sperma, meaning "seed".

Evolution

It is generally accepted that isogamy is the ancestor to sperm and eggs. Because there are no fossil records of the evolution of sperm and eggs from isogamy, there is a strong emphasis on mathematical models to understand the evolution of sperm.[4]

A widespread hypothesis states that sperm evolved rapidly, but there is no direct evidence that sperm evolved at a fast rate or before other male characteristics.[5]

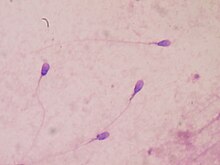

Sperm in animals

Function

The main sperm function is to reach the

The nuclear DNA in sperm cells is haploid, that is, they contribute only one copy of each paternal chromosome pair. Mitochondria in human sperm contain no or very little DNA because mtDNA is degraded while sperm cells are maturing, hence they typically do not contribute any genetic material to their offspring.[6]

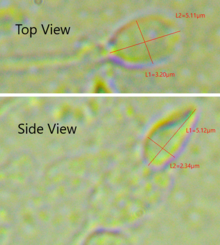

Anatomy

The mammalian sperm cell can be divided in 2 parts connected by a neck:

- Head: contains the nucleus with densely coiled chromatin fibers, surrounded anteriorly by a thin, flattened sac called the acrosome, which contains enzymes used for penetrating the female egg. It also contains vacuoles.[7]

- Tail: also called the flagellum, is the longest part and capable of wave-like motion that propels sperm for swimming and aids in the penetration of the egg.[8][9][10] The tail was formerly thought to move symmetrically in a helical shape.

- Neck: also called connecting piece contains one typical centriole and one atypical centriole such as the .

During

Origin

The spermatozoa of

In 2016, scientists at

Sperm quality

Sperm quantity and quality are the main parameters in semen quality, which is a measure of the ability of semen to accomplish

DNA damages present in sperm cells in the period after meiosis but before fertilization may be repaired in the fertilized egg, but if not repaired, can have serious deleterious effects on fertility and the developing embryo. Human sperm cells are particularly vulnerable to free radical attack and the generation of oxidative DNA damage,[19] such as that from 8-Oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine.

The postmeiotic phase of mouse spermatogenesis is very sensitive to environmental genotoxic agents, because as male germ cells form mature sperm they progressively lose the ability to repair DNA damage.[20] Irradiation of male mice during late spermatogenesis can induce damage that persists for at least 7 days in the fertilizing sperm cells, and disruption of maternal DNA double-strand break repair pathways increases sperm cell-derived chromosomal aberrations.[21] Treatment of male mice with melphalan, a bifunctional alkylating agent frequently employed in chemotherapy, induces DNA lesions during meiosis that may persist in an unrepaired state as germ cells progress through DNA repair-competent phases of spermatogenic development.[22] Such unrepaired DNA damages in sperm cells, after fertilization, can lead to offspring with various abnormalities.

Sperm size

Related to sperm quality is sperm size, at least in some animals. For instance, the sperm of some species of fruit fly (Drosophila) are up to 5.8 cm long—about 20 times as long as the fly itself. Longer sperm cells are better than their shorter counterparts at displacing competitors from the female's seminal receptacle. The benefit to females is that only healthy males carry "good" genes that can produce long sperm in sufficient quantities to outcompete their competitors.[23][24]

Market for human sperm

Some sperm banks hold up to 170 litres (37 imp gal; 45 US gal) of sperm.[25]

In addition to ejaculation, it is possible to extract sperm through testicular sperm extraction.

On the global market,

History

Sperm were first observed in 1677 by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek[29] using a microscope. He described them as being animalcules (little animals), probably due to his belief in preformationism, which thought that each sperm contained a fully formed but small human.[citation needed]

Forensic analysis

Ejaculated fluids are detected by

Sperm in plants

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2021) |

Sperm cells in algal and many plant

Motile sperm cells

Motile sperm cells typically move via flagella and require a water medium in order to swim toward the egg for fertilization. In animals most of the energy for sperm motility is derived from the metabolism of

Motile sperm are also produced by many protists and the gametophytes of bryophytes, ferns and some gymnosperms such as cycads and ginkgo. The sperm cells are the only flagellated cells in the life cycle of these plants. In many ferns and lycophytes, cycads and ginkgo they are multi-flagellated (carrying more than one flagellum).[34]

In nematodes, the sperm cells are amoeboid and crawl, rather than swim, towards the egg cell.[35]

Non-motile sperm cells

Non-motile sperm cells called spermatia lack flagella and therefore cannot swim. Spermatia are produced in a spermatangium.[34]

Because spermatia cannot swim, they depend on their environment to carry them to the egg cell. Some

Fungal spermatia (also called pycniospores, especially in the Uredinales) may be confused with

Sperm nuclei

In almost all

In some protists, fertilization also involves sperm nuclei, rather than cells, migrating toward the egg cell through a fertilization tube. Oomycetes form sperm nuclei in a syncytical antheridium surrounding the egg cells. The sperm nuclei reach the eggs through fertilization tubes, similar to the pollen tube mechanism in plants.[34]

Sperm centrioles

Most sperm cells have centrioles in the sperm neck.[38] Sperm of many animals has two typical centrioles, known as the proximal centriole and distal centriole. Some animals (including humans and bovines) have a single typical centriole, the proximal centriole, as well as a second centriole with atypical structure.[11] Mice and rats have no recognizable sperm centrioles. The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster has a single centriole and an atypical centriole named the proximal centriole-like.[39]

Sperm tail formation

The sperm tail is a specialized type of cilium (aka flagella). In many animals the sperm tail is formed through the unique process of cytosolic ciliogenesis, in which all or part of the sperm tail's axoneme is formed in the cytoplasm or gets exposed to the cytoplasm.[40]

See also

- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

- Female sperm

- Female sperm storage

- Mendelian inheritance

- Polyspermy

- Sperm competition

- Sperm granuloma

- Sperm theft

Citations

- ^ "Spermatium definition and meaning". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- ISBN 978-81-219-2618-8.

- ^ "Animal reproductive system - Male systems". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- ISBN 978-0-08-091987-4.

- PMID 32752988.

- PMID 37723262.

- PMID 25780567.

- ^ Fawcett, D. W. (1981) Sperm Flagellum. In: The Cell. D. W. Fawcett. Philadelphia, W. B. Saunders Company. 14: pp. 604-640.

- ^ Lehti, M. S. and A. Sironen (2017). "Formation and function of sperm tail structures in association with sperm motility defects." Bi

- .

- ^ PMID 29880810.

- PMID 19293139.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-3769-2. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ^ Semen and sperm quality

- PMID 6518230.

- S2CID 87014225.

- ^ Gurevich, Rachel (2008-06-10). "Does Age Affect Male Fertility?". About.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-28. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ a b Singh NP, Muller CH, Berger RE. Effects of age on DNA double-strand breaks and apoptosis in human sperm. Fertil Steril. 2003 Dec;80(6):1420-30. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.04.002. PMID: 14667878

- PMID 26178844.

- S2CID 1316244.

- PMID 17978187.

- PMID 25567288.

- S2CID 4407752.

- PMID 27225117.

- ^ Sarfraz Manzoor (2 November 2012). "Come inside: the world's biggest sperm bank". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ a b c Assisted Reproduction in the Nordic Countries Archived 2013-11-11 at the Wayback Machine ncbio.org

- ^ a b FDA Rules Block Import of Prized Danish Sperm Posted Aug 13, 08 7:37 AM CDT in World, Science & Health

- ^ a b Steven Kotler (26 September 2007). "The God of Sperm".

- ^ "Timeline: Assisted reproduction and birth control". CBC News. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- .

- PMID 11305439.

- ^ Illinois State Police/President's DNA Initiative. "The Presidents's DNA Initiative: Semen Stain Identification: Kernechtrot" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-26. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ISBN 978-1-78923-236-3.

- ^ ISBN 0-7167-1007-2.

- PMID 11839788.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 1-84265-153-6.

- PMID 10072316.

- PMID 25883936.

- PMID 19293139.

- PMID 26654377.

General and cited sources

- Fawcett, D. W. (1981). "Sperm Flagellum". In: D. W. Fawcett. The Cell, 2nd ed (OCLC 993416586.

- Lehti, M. S. and A. Sironen (October 2017). "Formation and function of sperm tail structures in association with sperm motility defects". Biol Reprod 97(4): 522–536. .