Spike Jonze

Spike Jonze | |

|---|---|

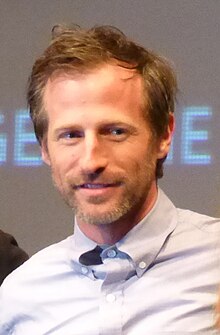

Jonze at the 2013 New York Film Festival | |

| Born | Adam Spiegel October 22, 1969 New York City, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1985–present |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Full list |

Adam Spiegel (born October 22, 1969),[1] known professionally as Spike Jonze (/dʒoʊnz/), is an American filmmaker, actor and photographer. His work includes films, commercials, music videos, skateboard videos and television.

Jonze began his career as a teenager photographing

Jonze began his feature film directing career with

He has worked as an actor sporadically throughout his career, co-starring in

Early life and education

Adam Spiegel was born on October 22, 1969, in

A keen BMX rider, Jonze began working at the Rockville BMX store in Rockville, Maryland, at the age of 16. A common destination for touring professional BMX teams, Jonze began photographing BMX demos at Rockville and formed a friendship with Freestylin' Magazine editors Mark Lewman and Andy Jenkins.[10] Impressed with Jonze's photography work, the pair offered him a job as a photographer for the magazine, and he subsequently moved to California to pursue career opportunities in photography.[10] Jonze fronted Club Homeboy, an international BMX club, alongside Lewman and Jenkins.[11] The three also created the youth culture magazines Homeboy and Dirt,[12] the latter of which was spun off from the female-centered Sassy and was aimed towards young boys.[13]

Career

1985–1993: Photography, magazines, and early video work

While shooting for various BMX publications in California, Jonze was introduced to a number of professional skateboarders who often shared ramps with BMX pros.[10] Jonze formed a close friendship with Mark Gonzales, co-owner of the newly formed Blind Skateboards at the time, and began shooting photos with the young Blind team including Jason Lee, Guy Mariano and Rudy Johnson in the late 1980s.[10] Jonze became a regular contributor to Transworld Skateboarding and was subsequently given a job at World Industries by Steve Rocco, who enlisted him to photograph advertisements and shoot promotional videos for his brands under the World Industries umbrella.[14] Jonze filmed, edited and produced his first skateboarding video, Rubbish Heap, for World Industries in 1989.[15] His following video project was Video Days, a promotional video for Blind Skateboards, which was released in 1991 and is considered to be highly influential in the community.[16] The video's subject, Gonzales, presented a copy of Video Days to Kim Gordon during a chance encounter following a Sonic Youth show in early 1992.[17] Impressed with Jonze's videography skills, Gordon asked him to direct a music video featuring skateboarders. The video, co-directed by Jonze and Tamra Davis, was for their 1992 single "100%", which featured skateboarding footage of Blind Skateboards rider Jason Lee, who later became a successful actor.[17] In 1993, Jonze co-directed the "trippy" music video for The Breeders song "Cannonball" with Gordon.[18]

Along with Rick Howard and

1995–1999: In demand video director and Being John Malkovich

Jonze collaborated with

Jonze filmed a short documentary in 1997,

The first feature film Jonze directed was Being John Malkovich in 1999. It stars John Cusack, Cameron Diaz, and Catherine Keener, with John Malkovich as himself. The screenplay was written by Charlie Kaufman and follows a puppeteer who finds a portal in an office that leads to the mind of actor John Malkovich. Kaufman's script was passed on to Jonze by his father-in-law Francis Ford Coppola and he agreed to direct it,[45] "delighted by its originality and labyrinthine plot".[46] Being John Malkovich was released in October 1999 to laudatory reviews; the Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert found the film to be "endlessly inventive" and named it the best film of 1999,[47][48] while Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly called it the "most excitingly original movie of the year".[49] At the 72nd Academy Awards, the film was nominated for Best Director, Best Original Screenplay and Best Supporting Actress for Keener.[50] Jonze co-starred opposite George Clooney, Mark Wahlberg and Ice Cube in David O. Russell's war comedy Three Kings (1999), which depicts a gold heist by four U.S. soldiers following the end of the Gulf War. Jonze's role in the film, the sweet, dimwitted, casually racist PFC Conrad Vig, was written specifically for him.[51] Jonze also directed a commercial for Nike called "The Morning After" in 1999, a parody of the hysteria surrounding Y2K.[52]

2000–2008: Adaptation and Jackass

Jonze returned to video directing in 2000, helming the video for the song "

Jonze co-founded

After directing videos for

2009–2019: Where the Wild Things Are, short films, and Her

Where the Wild Things Are (2009), a film adaptation of Maurice Sendak children's picture book of the same name, was directed by Jonze and co-written by Jonze and Dave Eggers, who expanded the original ten-sentence book into a feature film.[79] Sendak gave advice to Jonze while he was adapting the book and the two developed a friendship.[80] The film stars Max Records as Max, a lonely 8-year-old boy who runs away from home after an argument with his mother (played by Catherine Keener) and sails away to an island inhabited by creatures known as the "Wild Things," who declare Max their king.[80] The Wild Things were played by performers in creature suits, while CGI was required to animate their faces.[81] James Gandolfini, Lauren Ambrose, Chris Cooper, Forest Whitaker, Catherine O'Hara, Paul Dano, and Michael Berry Jr. provided the voices for the Wild Things, and Jonze voiced two owls named Bob and Terry.[82] The film's soundtrack was performed by Karen O and composer Carter Burwell scored his third film for Jonze.[83] Where the Wild Things Are was released in October 2009 to a generally positive critical reception but did not perform well at the box office. Some reviewers were unsure whether the film was intended for a younger or adult audience due to its dark tone and level of maturity.[84] Jonze himself said that he "didn't set out to make a children's movie; I set out to make a movie about childhood".[85] A television documentary, Tell Them Anything You Want: A Portrait of Maurice Sendak, co-directed by Jonze and Lance Bangs, aired in 2009 and features a series of interviews with Sendak.[86] Jonze wrote and directed We Were Once a Fairytale (2009), a short film starring Kanye West as himself acting belligerently while drunk in a nightclub.[87]

Jonze wrote and directed the science fiction romance short film

Jonze's fourth feature film, the romantic science fiction drama Her, was released in December 2013. The film was his first original screenplay and the first he had written alone, inspired by Charlie Kaufman by putting "all the ideas and feelings at that time" into his script for Synecdoche, New York.[99] It stars Joaquin Phoenix, Amy Adams, Rooney Mara, Olivia Wilde, and Scarlett Johansson. The film follows the recently divorced Theodore Twombly (Phoenix), a man who develops a relationship with a seemingly intuitive and humanistic female voice, named "Samantha" (Johansson), produced by an advanced computer operating system.[99] Samantha was originally voiced by Samantha Morton during its production, but was later replaced by Johansson.[99] Jonze provided his voice to a video game character in the film, Alien Child, who interacts with Theodore.[100] The film's score was composed by Arcade Fire and Owen Pallett.[101]

Her was met with universal acclaim from critics.[102] Todd McCarthy of The Hollywood Reporter praised Jonze for taking an old theme "the search for love and the need to 'only connect'" and embracing it "in a speculative way that feels very pertinent to the moment and captures the emotional malaise of a future just an intriguing step or two ahead of contemporary reality."[103] Scott Foundas of Variety opined that it was Jonze's "richest and most emotionally mature work to date".[104] At the 86th Academy Awards, Jonze was nominated for three Academy Awards for Her, winning for Best Original Screenplay and receiving further nominations for Best Picture and Best Original Song for co-writing "The Moon Song" with Karen O.[105] Jonze won the Golden Globe Award for Best Screenplay at the 71st Golden Globe Awards.[106]

Jonze co-wrote, co-produced, and appeared in

In 2017, Jonze directed

2020–present: Beastie Boys Story

Jonze directed the Beastie Boys Story: As Told By Michael Diamond & Adam Horovitz stage show, which took place in Philadelphia and Brooklyn for three nights in 2019 and saw the band's two surviving members tell the story of the Beastie Boys and their friendship.[123] A feature-length documentary, Beastie Boys Story, was also directed by Jonze and features footage from the shows.[123] It was released on Apple TV+ in 2020 to positive reviews.[124] He returned to acting in Damien Chazelle's 2022 film Babylon, appearing as a German film director bearing a resemblance to Erich von Stroheim.[125]

Personal life

On June 26, 1999, Jonze married director Sofia Coppola, whom he had first met in 1992 on the set of the music video for Sonic Youth's "100%".[3][126] On December 5, 2003, the couple filed for divorce, citing "irreconcilable differences".[126] The character of John, a career-driven photographer (played by Giovanni Ribisi) in Coppola's Lost in Translation (2003), was rumored to be based on Jonze, though Coppola commented "It's not Spike, but there are elements of him there, elements of experiences."[127]

Jonze dated singer Karen O throughout 2005, although the couple broke up shortly after.[128] People magazine reported that Jonze dated actress Drew Barrymore in 2007.[129] From 2008 to 2009, Jonze dated actress Michelle Williams, with whom he worked on Synecdoche, New York.[130] Jonze was reported to have begun dating Japanese actress Rinko Kikuchi in 2010 and the couple briefly lived together in New York City.[131][132] They separated in 2011.[133]

Jonze has twins with DJ Allie Teilz who were born in 2023.[134]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Being John Malkovich | USA Films / Universal Pictures |

| 2002 | Adaptation | Sony Pictures Releasing

|

| 2009 | Where the Wild Things Are | Warner Bros. Pictures |

| 2013 | Her |

Awards and nominations

| Year | Title | Academy Awards | BAFTA Awards | Golden Globe Awards | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | ||

| 1999 | Being John Malkovich | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

| 2002 | Adaptation | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 2 |

| 2009 | Where the Wild Things Are | 1 | |||||

| 2013 | Her | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Total | 12 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 14 | 3 | |

References

- ISBN 978-0-73332-052-1.

...born: Adam Spiegel, October 22, 1969

- ^ "Spike Jonze The Nine Club With Chris Roberts - Episode 78". YouTube. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Smith, Ethan (October 18, 1999). "Spike Jonze Unmasked". New York. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Obituary for Spiegel". Albuquerque Journal. June 27, 2000. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Bloom, Nate (October 16, 2009). "Jewish Stars 10/16 – Cleveland Jewish News: Archives". Cleveland Jewish News. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Pappademas, Alex (December 17, 2013). "Career Arc: Spike Jonze". Grantland. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Mottram, James (January 31, 2014). "Spike Jonze interview: Her is my 'boy meets computer' movie". The Independent. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Tewksbury, Drew (July 22, 2010). "The Continuing Adventures of Squeak E. Clean". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Director Jeff Tremaine Talks 'Bad Grandpa'". Military.com. January 28, 2014. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d O'Dell, Patrick (September 20, 2017). "Spike Jonze". Epicly Later'd. Season 1. Episode 3. Viceland. Archived from the original on June 5, 2023.

- ^ Lewman, Mark (December 18, 2009). "Spike Jonze Tribute – Ask What If". Huck. Archived from the original on June 10, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ Y. Moss, Marie (September 4, 1991). "Here's The Dirt". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Elizabeth Williams, Mary (August 1, 1995). "Dirt Alumni Clean Up". Wired. Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Tony, Owen (April 10, 2010). "How One Man Changed Skateboarding Forever". Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Gandert, Sean (March 26, 2009). "Salute Your Shorts: Spike Jonze Skate Videos". Paste. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ a b Hammond, Stuart (May 1, 2016). "Spike Jonze skates against the grain". Dazed. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ a b "17 Essential Music Videos for Skate Fans". Vogue. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Stiernberg, Bonnie (July 6, 2011). "Our 15 Favorite Spike Jonze-Directed Music Videos". Paste. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ Cox, Stephen (November 5, 2014). "20 Years of Girl: Spike Jonze Interview". The Deaf Lens. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Phull, Hardeep (January 25, 2017). "How Mary Tyler Moore became an unlikely icon for '90s kids". New York Post. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (December 9, 1994). "Weezer loves "Happy Days"". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ a b "Readers' Poll: The 10 Greatest Music Videos of the 1990s". Rolling Stone. October 23, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Pitchfork. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ L. Cooper, Carol. "Beastie Boys". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (June 24, 2009). "Weezer's 'Undone – The Sweater Song' Turns 15: A Look Back". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ "Mi Vida Loca". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

several musicians and film directors also make cameos, among them Spike Jonze

- ^ a b Ehrlich, David (March 3, 2015). "The 10 best Bjork music videos". Time Out. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ King, Susan (January 8, 1995). "Generations X-Press : English / Shukovsky Sitcom Leads With Bike Messengers and 'Murphy's' Former Painter". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (March 17, 1995). "Spike Jonze: The Sheik of Geek". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Vulture. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Sciretta, Peter (June 17, 2008). "VOTD: Spike Jonze's 1997 Short Film How They Get There". /Film. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Complex. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Slant. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Wagoner, Allison (July 15, 2012). "Spike Jonze's Top 9 Music Videos". Houston Press. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Dentler, Matt (September 3, 2009). "Pavement's Best Video: Shady Lane by Spike Jonze". IndieWire. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Mlynar, Phillip (August 15, 2011). "Top Five Spike Jonze Rap Videos That Are Better Than "Otis"". LA Weekly. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Susman, Gary (September 12, 2017). "14 Things You Never Knew About David Fincher's 'The Game'". Moviefone. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ Sciretta, Peter (August 25, 2009). "The Museum of Modern Art Presents Spike Jonze: The First 80 Years". /Film. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawerence (September 11, 1998). "'Free Tibet': Good Causes Don't Always Make Good Films". The New York Times. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Wickman, Forrest (December 19, 2013). "The Short Films of Spike Jonze—and What They Can Tell Us About Her". Slate. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ "Fatboy Slim Rolls With Jonze". NME. May 12, 1998. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Landay, Vincent (Producer) Brown, Richard (Producer) (2003). The Work of Director Spike Jonze (DVD). New York City: Palm Pictures. Event occurs at Side A, Commentry Track of Praise You spoken by Normal Cook (Fatboy Slim).

- ^ "Fatboy Slim's Praise You voted best video". The Guardian. July 31, 2001. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Ives, Brian (September 9, 1999). "Spike Jonze Highlights Fatboy Slim's VMA "Performance"". MTV News. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Villarreal, Phil (January 7, 2007). "Being John Malkovich a quirky wonder". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

- ^ Kobel, Peter (October 24, 1999). "The Fun and Games of Living a Virtual Life". The New York Times. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 29, 1999). "Being John Malkovich". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 31, 1999). "The Best 10 Movies Movies of 1999". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (November 12, 1999). "Being John Malkovich". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ "Nominees & Winners for the 72nd Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ Wolk, Josh (October 1, 1999). "George Clooney fought to star in Three Kings". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Grandy Taylor, Frances (December 10, 2009). "Why Worry? Y2K Is Funny Fodder for Ads". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Willman, Chris (September 14, 2001). "Tenacious D's Date with Spike Jonze". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Anne Hughes, Sarah (June 27, 2011). "Johnny Knoxville, Spike Jonze pen emotional tributes to Ryan Dunn". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Crouch, Ian (January 24, 2014). ""Mitt," Al Gore, and Our Identification With Presidential Losers". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Levy, Glen (July 26, 2011). "The 30 All-TIME Best Music Videos". Time. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ "Slim's 'Weapon' Bulges With Six MTV VMAs". Billboard. September 7, 2001. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ "Grammys 2002: The winners". BBC News. February 28, 2002. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Leigh, Danny (February 14, 2003). "Let's make a meta-movie". The Guardian. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ "Adaptation (2002)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Elise, Marianne (October 3, 2017). "An Oral History of 'Jackass: The Movie'". Vice. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Wild, David (January 23, 2003). "Spike Jonze: The Man Who Wasn't There". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Elliot, Stuart (September 16, 2002). "Ikea challenges the attachment to old stuff, in favor of brighter, new stuff". The New York Times. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Nudd, Tim (June 16, 2014). "Spike Jonze Reveals His Favorite Ad and How to Stay Creative With Clients Around". Adweek. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Pinkerton, Nick (October 6, 2009). "Spike Jonze Gets His Long-Overdue MOMA Retrospective". The Village Voice. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Baltimore, Megan (September 16, 2003). "Behind the Video: Girl Skateboards' Yeah Right". Transworld Skateboarding. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Fossum, Tommy (April 8, 2003). "Jackass-dramatikk for Turboneger". dagbladet.no (in Norwegian). Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ "Chris Cunningham, Michel Gondry & Palm Pictures Present The Directors Label; Director-Compiled DVD Series to Debut October 28". Business Wire. September 17, 2003. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- Advertising Age. April 1, 2005. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ "O My God!". NME. April 13, 2005. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Endelman, Michael (October 8, 2004). "Yeah Yeah Yeahs explain their disturbing new video". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Foundas, Scott (September 19, 2006). "Jackass: Number Two". The Village Voice. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Sullivan, Caroline (September 29, 2006). "Beck, The Information". The Guardian. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Levine, Robert (November 19, 2007). "A Guerrilla Video Site Meets MTV". The New York Times. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Tanz, Jason (October 18, 2007). "The Snarky Vice Squad Is Ready to Be Taken Seriously. Seriously". Wired. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Slant. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Rodriguez, Jayson (February 15, 2008). "Kanye West's Latest Video Vixen Defends 'Flashing Lights' Clip: "It's Whatever You Want It To Be"". MTV News. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Carr, David (October 19, 2008). "The Universe According to Kaufman". The New York Times. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (October 16, 2009). "Where the Wild Things Are". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Knafo, Saki (September 2, 2009). "Bringing 'Where the Wild Things Are' to the Screen". The New York Times. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Sancton, Julian (October 17, 2009). "Where the Wild Things Are Built: Jim Henson's Creature Shop". Vanity Fair. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Pahle, Rebecca (November 11, 2015). "10 Wild Facts About Where the Wild Things Are". Mental Floss. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Solarski, Matthew (January 16, 2008). "Karen O Pens Tunes for Jonze/Eggers Wild Things Film". Pitchfork. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- The Atlantic. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Wong, Grace (October 14, 2009). "Spike Jonze goes 'Where the Wild Things Are'". CNN. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Murray, Noel (October 19, 2009). "Tell Them Anything You Want: A Portrait Of Maurice Sendak". The A.V. Club. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (October 22, 2009). "Spike Jonze Explains His Kanye West Mini-Movie, 'We Were Once a Fairytale'". The New York Times. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- Slant. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Sciretta, Peter (February 16, 2010). "Photos and Video From the Spike Jonze-Produced Short Film Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More to Life". /Film. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Bettinger, Brendan (April 19, 2010). "Spike Jonze Co-Directed "Drunk Girls" Music Video for LCD Soundsystem". Collider. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (March 18, 2011). "SXSW Review: Spike Jonze & Arcade Fire's 'Scenes From The Suburbs' An Intense Look At Fading Youth". IndieWire. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Biddlecombe, Sarah (November 1, 2014). "Songs inspired by the suburbs". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- Vulture. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Ferguson, LaToya (January 8, 2016). "Are you now or have you ever been Todd Margaret?". The A.V. Club. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Montgomery, James (August 11, 2011). "Jay-Z And Kanye 'Otis' Video: Maybach Massacre". MTV News. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Slant. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Vulture. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Fischer, Russ (November 30, 2012). "'Pretty Sweet' Trailer: Spike Jonze Returns to Skateboarding". /Film. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c Michael, Chris (September 9, 2013). "Spike Jonze on letting Her rip and Being John Malkovich". The Guardian. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Gorochow, Erica (February 13, 2014). "Meet The Real World Designers Behind The Fictional Video Games Of 'Her". The Creators Project. Vice Media. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Battan, Carrie (February 20, 2014). "Watch: Arcade Fire and Owen Pallett's Her Score, Behind the Scenes". Pitchfork. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- ^ "Her Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (October 12, 2013). "Her: Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Foundas, Scott (October 12, 2013). "Film Review: 'Her'". Variety. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ "The 86th Academy Awards (2014) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. AMPAS. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- ^ Los Angeles Times (January 12, 2014). "Golden Globes 2014: The complete list of nominees and winners". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (October 26, 2013). "Review: 'Jackass Presents: Bad Grandpa' Starring Johnny Knoxville And Co-Written & Produced By Spike Jonze". IndieWire. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ "Spike Jonze to direct live music videos for Arcade Fire and Lady Gaga at YouTube Awards". NME. October 31, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Pitchfork. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Gibson, Megan (August 1, 2014). "Spike Jonze Will Appear on Girls Next Season". Time. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Vine, Richard (August 31, 2016). "Spike Jonze gets freaky for Kenzo – where film meets beauty". The Guardian. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Guthrie, Marisa (November 3, 2015). "It's Official: Vice Channel to Take Over A+E Networks' History Spinoff H2". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ "Frank Ocean had a legendary director film his first New York concert in 5 years". Business Insider France (in French). Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ Ryzik, Melana (September 8, 2017). "Twirly Legs and All: Spike Jonze Spreads His Dance Wings". The New York Times. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Stolworthy, Jacob (December 22, 2017). "Jim and Andy: Spike Jonze and Chris Smith on documentary charting Jim Carrey's controversial transformation into comedian Andy Kaufman". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (March 6, 2018). "Spike Jonze Returns For A Surreal Apple Short Film Starring Double FKA Twigs — Watch". IndieWire. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Obenson, Tambay (January 30, 2019). "Spike Jonze Directs Idris Elba in Charming Comedy Short Film for Squarespace". IndieWire. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (March 1, 2019). "Spike Jonze Directs Short Film Advocating for Marijuana Legalization — Watch". IndieWire. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ St. Félix, Doreen (July 13, 2019). "The Productive Ambivalence of Aziz Ansari in His Comeback Netflix Special". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ "71st Annual DGA Awards Winners -". www.dga.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ "72nd Annual DGA Awards Winners -". www.dga.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Kohn, Eric (April 20, 2020). "'Beastie Boys Story' Review: Spike Jonze Directs a Moving Nostalgia Trip as the Rappers Tell Their Story". IndieWire. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Beastie Boys Story Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Belinchón, Gregorio (January 21, 2023). "'Babylon:' A love song to the lawless years of Hollywood". El País. Archived from the original on August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ a b "Sofia Coppola, Spike Jonze to divorce". USA Today. December 9, 2003. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Valby, Karen (July 26, 2007). "Sofia Coppola talks about 'Lost in Translation'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Mulkerrins, Jane (September 6, 2014). "Yeah Yeah Yeahs frontwoman Karen O talks about going it alone and her new solo album Crush Songs". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ People Staff (July 11, 2007). "Drew Barrymore Reunites with Spike Jonze". People. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- US Weekly. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "Rinko Kikuchi dating director Spike Jonze". Japan Today. September 7, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Wiseman, Eva (February 27, 2011). "Rinko Kikuchi: the interview". The Guardian. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Kikuchi Rinko and Spike Jonze no more". news.yahoo.com. May 15, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ @allieteilz (January 27, 2024). "we are over the moon with the expansion of our family blessed with the birth of beautiful twins! the sweetest boys in the world on the day they were born i had eden ahbez 'nature boy' sung by nat king cole floating around my head... the greatest thing you'll ever learn is just to love and be love in return 💓💓💓". Retrieved March 3, 2024 – via Instagram.

Further reading

- OCLC 56617315.

External links

- Spike Jonze at IMDb

- Spike Jonze at AllMovie