Sponge reef

Sponge reefs are

Sponge reefs were once a dominant landscape in the

Like

Characteristics of hexactinellid sponges

Hexactinellids, or "glassy" sponges are characterized by a rigid framework of spicules made of

As a result, the sponge has a distinctive electrical conduction system across its body. This allows the sponge to rapidly respond to disturbances such as a physical impact or excessive sediment in the water. The sponge's response is to stop feeding. It will try to resume feeding after 20–30 minutes, but will stop again if the irritation is still present.[3]

Hexactinellids are exclusively marine and are found throughout the world in deep (>1000 m) oceans.[5] Individual sponges grow at a rate of 0–7 cm/year, and can live to be at least 220 years old.[6] Little is known about hexactinellid sponge reproduction. Like all poriferans, the hexactinellids are filter feeders. They obtain nutrition from direct absorption of dissolved substances, and to a lesser extent from particulate materials.[5]

There are no known predators of healthy reef sponges.[6] This is likely because the sponges possess very little organic tissue; the siliceous skeleton accounts for 90% of the sponge body weight.[5]

Hexasterophoran sponges have spicules called hexactines that have six rays set at right angles. Orders within hexasterophora are classified by how tightly the spicules interlock with Lyssanctinosan spicules less tightly interlocked than those of Hexactinosan sponges.

The primary frame-building sponges are all members of the order Hexactinosa, and include the species Chonelasma/Heterochone calyx (chalice sponge), Aphrocallistes vastus (cloud sponge), and Farrea occa.[6] Hexactinosan sponges have a rigid scaffolding of "fused" spicules that persists after the death of the sponge.

Other sponge species abundant on sponge reefs are members of the order Lyssactinosa (Rosselid sponges) and include Rhabdocalyptus dawsoni (boot sponge), Acanthascus platei, Acanthascus cactus and Staurocalyptus dowlingi.[6] Rosselid sponges have a "woven" or "loose" siliceous skeleton that does not persist after the death of the sponge, and are capable of forming mats, but not reefs.[3]

Location of sponge reefs

Although hexactinellid sponges are found worldwide in deep seawater, the only place that they are known to form reefs is between south east Alaska and off

Four hexactinellid reefs were discovered in the Queen Charlotte Basin (QCB) in 1987–1988.[2] Three more reefs were reported in the Georgia Basin (GB) in 2005.[7] The QCB reefs are found 70–80 km from the coastline in water 165–240 m deep.[6] These reefs cover over 700 km² of the ocean floor.[5]

Sponge reefs require unique conditions, which may explain their global rarity. They are found only in glacier-scoured troughs of low-angle continental shelf. The seafloor is stable and consists of rock, coarse gravel, and large boulders.[5] Hexactinellid sponges require a hard substrate, and do not anchor to muddy or sandy sea floors.[6]

They are found only where sedimentation rates are low, dissolved silica is high (43–75 μM), and bottom currents are between 0.15 and 0.30 m/s.[5] Dissolved oxygen is low (64–152 μM), and temperatures are a cool 5.5-7.3 °C at the reefs.[5] Surface temperatures range between 6 °C in April and 14 °C in August.[6]

Downwellings are common in Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound, especially in winter, but there is an occasional summer upwelling.[5] These upwellings bring nutrient-rich waters to the sponge reefs.

Structure of sponge reefs

Each living sponge on the surface of the reef can be over 1.5 m tall. The reefs are composed of mounds called "bioherms" that are up to 21 m high, and sheets called "biostromes" that are 2–10 m thick and may be many kilometers wide.[5]

Each sponge in the order Hexactinosa has a rigid skeleton that persists after the death of the animal. This provides an excellent substrate for sponge larvae to settle upon, and new sponges grow on the framework of past generations. The growth of sponge reefs is thus analogous to that of

Deep ocean currents carry fine sediments that are captured by the scaffolding of sponge reefs. A sediment matrix of silt, clay, and some sand forms around the base of the sponge bioherms. The sediment matrix is soft near the surface, and firm below one metre deep.[6] Dead sponges become covered in sediment, but do not lose their supportive siliceous skeleton.[6] The sponge sediments have high levels of silica and organic carbon. The reefs grow parallel to the glacial troughs, and the morphology of reefs is due to deep currents.[7]

In the fossil record

Hexactinellids first appeared in the fossil record during the Late

The sponge reefs declined throughout the

It is estimated through radiocarbon dating of reef cores that the reefs have been living on the continental shelf of Western Canada for 8,500–9,000 years.[2]

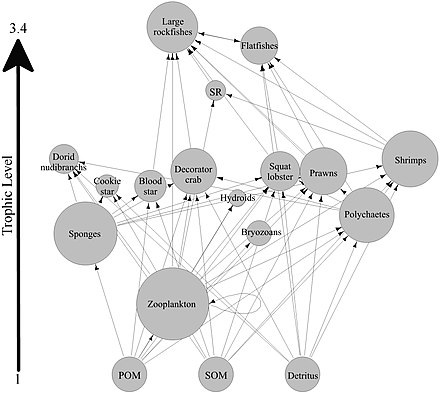

Ecological significance

Sponge reefs provide structure on the otherwise relatively featureless continental shelf. They provide habitat for fish and invertebrates, and may serve as an important nursery area for these animals. More research is required to determine the full ecological importance of these reefs.[2][3]

Observations by manned submersible indicate that the fauna of sponge reefs differs from surrounding areas.

Destruction of sponge reefs

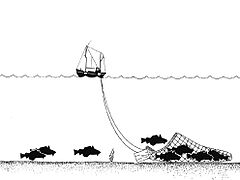

The reefs are susceptible to damage by fishing, especially bottom trawling and dredging. In typical groundfish trawling, a large net is dragged across the ocean floor, its mouth held open by two 2 tonne doors called otterboards. The siliceous skeleton of the sponges is fragile, and these organisms are easily broken by physical impact. The impacts of bottom trawling have been observed in three of the reefs in the QCB.[3] Trawling damage appears as parallel tracks 70–100 m apart that may extend for several kilometers. Each trawl track is 10 cm deep, 20 cm wide, and occurs at depths of 210–220 m. Sponges in the vicinity of trawl tracks are shattered or completely removed.

While less harmful, hook and line fishing as well as crustacean trapping may also damage the reefs. When the fishing gear is hauled to the surface, the lines and traps drag along the ocean floor and have the potential to break corals and sponges. Broken sponge "stumps", as well as those with abraded sides, were found in regions where line and trap fishing took place.[3]

Breakage of reef sponges may have dire consequences for the recruitment of new sponges, as sponge larvae require the siliceous skeletons of past generations as a substrate.[6] Without a hard substrate, new sponges cannot settle and regrow broken parts of the reef. It has been estimated that broken sponge reefs may take up to 200 years to recover.[3]

In addition, offshore oil and gas exploration threatens the reefs. The government of British Columbia has lifted a moratorium preventing exploratory drilling and tanker traffic in Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound, and the area has been leased by the oil and gas industry.[3] Even if exploratory drilling is not done on or immediately adjacent to the reefs, it may still have a negative impact by increasing the amount of sediment in the seawater, or through hydrocarbon pollution.[4]

Protection

In 1999,

Protection of the four sponge reefs in Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound was included as a "management issue" in the 2005/06 groundfish trawling management plan.[10] The management plan recommended that an additional 9 km (5.6 mi) buffer zone around the reefs be added to the existing groudfish trawl closures.[3] The reefs were also being considered as locations for future Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).[3] Although MPAs may be more effective than fishery closures for long-term protection of the reefs from bottom trawling, the oil and gas industry would still pose a threat.[10]

In 2008, the issue of preserving sensitive underwater ecosystems along the North Coast of British Columbia were consolidated within the Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area. The goal was to develop a plan to conserve this relatively undeveloped region, while fostering sustainable economies on the coast, which promised to make Canada a world leader in marine conservation. However, in 2011, the ministry withdrew support for the process in favour of greater consistency with ocean planning on the other coasts of Canada.

In February 2017, the sponge reefs of Hecate Sound and Queen Charlotte Sound were formally protected within the Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reefs Marine Protected Area. The marine protected area covers an area of 2,410 km2 (930 sq mi) and prohibits any activity that could disturb or destroy the sponge reefs.[11]

See also

- Hexactinellid sponges (glass sponges)

- Cloud sponge

- Sponge Reef Project

References

- S2CID 52015990.

- ^ a b c d e f

Hexactinellid sponge reefs on the British Columbia continental shelf: Geological and biological structure (Report). DFO Pacific Region Habitat Status Report. Department of Fisheries and Oceans. February 2000. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n

Jamieson, G.S.; Chew, L. (2002). Hexactinellid sponge reefs: Areas of interest as marine protected areas in the north and central coast areas (Report). Can Sci Adv Sec Res Doc. Vol. 12. - ^ a b Protecting the glass sponge reefs from offshore oil and gas (PDF) (Report). Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2004. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 128410530.

- ^ S2CID 129356194.

- doi:10.1139/e91-040.

- ISSN 2296-7745..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - ^ a b

Groundfish trawl integrated fisheries management plan (PDF) (Report). Department of Fisheries and Oceans. 2005. Retrieved 28 March 2008. - ^ "Hecate Strait/Queen Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reefs Marine Protected Area (HS/QCS MPA)". Fisheries and Oceans Canada. www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca (Press release). Government of Canada. 18 September 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

External links

- The Sponge Reef Project - Accessed on March 25, 2008

- Natural Resources Canada - Sponge Reefs on the continental shelf - Accessed on March 25, 2008.

- Austin, W. C. 2003 - Sponge gardens: A hidden treasure in British Columbia - Accessed on March 25, 2008

- University of California Museum of Paleontology - Hexactinellida - Accessed on April 7, 2008