Sri Lanka

Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: " Sri Lankan | |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic[6] |

| Ranil Wickremesinghe | |

| Dinesh Gunawardena | |

| Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena | |

| Jayantha Jayasuriya | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Formation | |

| 543 BCE | |

| 377 BCE–1017 CE | |

| 1017–1232 | |

| 1232–1592 | |

| 1592–1815 | |

| 1815–1948 | |

| 4 February 1948 | |

• Republic | 22 May 1972 |

| 7 September 1978 | |

.இலங்கை | |

Website gov.lk | |

Sri Lanka, in the northwest.

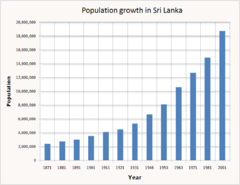

Sri Lanka has a population of approximately 22 million and is home to many cultures, languages and ethnicities. The Sinhalese people form the majority of the population, followed by the Sri Lankan Tamils, who are the largest minority group and are concentrated in northern Sri Lanka; both groups have played an influential role in the island's history. Other long-established groups include the Moors, Indian Tamils, Burghers, Malays, Chinese, and Vedda.[13]

Sri Lanka's documented history goes back 3,000 years, with evidence of prehistoric human settlements dating back 125,000 years.

Sri Lanka is a

Toponymy

In antiquity, Sri Lanka was known to travellers by a variety of names. According to the Mahāvaṃsa, the legendary Prince Vijaya named the island Tambapaṇṇĩ ("copper-red hands" or "copper-red earth"), because his followers' hands were reddened by the red soil of the area where he landed.[22][23] In Hindu mythology, the term Lankā ("Island") appears but it is unknown whether it refers to the modern-day state. The Tamil term Eelam (Tamil: ஈழம், romanized: īḻam) was used to designate the whole island in Sangam literature.[24][25] The island was known under Chola rule as Mummudi Cholamandalam ("realm of the three crowned Cholas").[26]

The country is now known in Sinhala as Śrī Laṅkā (Sinhala: ශ්රී ලංකා) and in Tamil as Ilaṅkai (Tamil: இலங்கை, IPA: [iˈlaŋɡaɪ]). In 1972, its formal name was changed to "Free, Sovereign and Independent Republic of Sri Lanka". Later, on 7 September 1978, it was changed to the "Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka".[32][33] As the name Ceylon still appears in the names of a number of organisations, the Sri Lankan government announced in 2011 a plan to rename all those over which it has authority.[34]

History

Prehistory

The pre-history of Sri Lanka goes back 125,000 years and possibly even as far back as 500,000 years.

The earliest inhabitants of Sri Lanka were probably ancestors of the

During the protohistoric period (1000–500 BCE) Sri Lanka was culturally united with southern India,

One of the first written references to the island is found in the Indian

Ancient history

According to the

Once

The Anuradhapura period (377 BCE – 1017 CE) began with the establishment of the Anuradhapura Kingdom in 380 BCE during the reign of Pandukabhaya. Thereafter, Anuradhapura served as the capital city of the country for nearly 1,400 years.[51] Ancient Sri Lankans excelled at building certain types of structures such as tanks, dagobas and palaces.[52] Society underwent a major transformation during the reign of Devanampiya Tissa, with the arrival of Buddhism from India. In 250 BCE,[53] Mahinda, a bhikkhu and the son of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka arrived in Mihintale carrying the message of Buddhism.[54] His mission won over the monarch, who embraced the faith and propagated it throughout the Sinhalese population.[55]

Succeeding kingdoms of Sri Lanka would maintain many

Sri Lanka experienced the first of many foreign invasions during the reign of

The

.Sri Lanka was the first Asian country known to have a female ruler: Anula of Anuradhapura (r. 47–42 BCE).[61] Sri Lankan monarchs undertook some remarkable construction projects such as Sigiriya, the so-called "Fortress in the Sky", built during the reign of Kashyapa I of Anuradhapura, who ruled between 477 and 495. The Sigiriya rock fortress is surrounded by an extensive network of ramparts and moats. Inside this protective enclosure were gardens, ponds, pavilions, palaces and other structures.[62][63]

In 993 CE, the invasion of

Post-classical period

Following a 17-year-long campaign,

Sri Lanka's

After his demise, Sri Lanka gradually decayed in power. In 1215, Kalinga Magha, an invader with uncertain origins, identified as the founder of the Jaffna kingdom, invaded and captured the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa. He sailed from Kalinga[72] 690 nautical miles on 100 large ships with a 24,000 strong army. Unlike previous invaders, he looted, ransacked and destroyed everything in the ancient Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa Kingdoms beyond recovery.[75] His priorities in ruling were to extract as much as possible from the land and overturn as many of the traditions of Rajarata as possible. His reign saw the massive migration of native Sinhalese people to the south and west of Sri Lanka, and into the mountainous interior, in a bid to escape his power.[76][77]

Sri Lanka never really recovered from the effects of Kalinga Magha's invasion. King Vijayabâhu III, who led the resistance, brought the kingdom to Dambadeniya. The north, in the meanwhile, eventually evolved into the Jaffna kingdom.[76][77] The Jaffna kingdom never came under the rule of any kingdom of the south except on one occasion; in 1450, following the conquest led by king Parâkramabâhu VI's adopted son, Prince Sapumal.[78] He ruled the North from 1450 to 1467 CE.[79]

The next three centuries starting from 1215 were marked by kaleidoscopically shifting collections of capitals in south and central Sri Lanka, including Dambadeniya,

Early modern period

The early modern period of Sri Lanka begins with the arrival of Portuguese soldier and explorer Lourenço de Almeida, the son of Francisco de Almeida, in 1505.[90] In 1517, the Portuguese built a fort at the port city of Colombo and gradually extended their control over the coastal areas. In 1592, after decades of intermittent warfare with the Portuguese, Vimaladharmasuriya I moved his kingdom to the inland city of Kandy, a location he thought more secure from attack.[91] In 1619, succumbing to attacks by the Portuguese, the independent existence of the Jaffna kingdom came to an end.[92]

During the reign of the Rajasinha II, Dutch explorers arrived on the island. In 1638, the king signed a treaty with the Dutch East India Company to get rid of the Portuguese who ruled most of the coastal areas.[93] The following Dutch–Portuguese War resulted in a Dutch victory, with Colombo falling into Dutch hands by 1656. The Dutch remained in the areas they had captured, thereby violating the treaty they had signed in 1638. The Burgher people, a distinct ethnic group, emerged as a result of intermingling between the Dutch and native Sri Lankans in this period.[94]

The Kingdom of Kandy was the last independent monarchy of Sri Lanka.

Eventually, with the support of

During the Napoleonic Wars, fearing that French control of the Netherlands might deliver Sri Lanka to the French, the British Empire occupied the coastal areas of the island (which they called the colony of British Ceylon) with little difficulty in 1796.[98] Two years later, in 1798, Sri Rajadhi Rajasinha, third of the four Nayakkar kings of Sri Lanka, died of a fever. Following his death, a nephew of Rajadhi Rajasinha, eighteen-year-old Kannasamy, was crowned.[99] The young king, now named Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, faced a British invasion in 1803 but successfully retaliated. The First Kandyan War ended in a stalemate.[99]

By then the entire coastal area was under the

The beginning of the modern period of Sri Lanka is marked by the

Soon, coffee became the primary commodity export of Sri Lanka. Falling coffee prices as a result of the

By the end of the 19th century, a new educated

The 1906 malaria outbreak in Ceylon actually started in the early 1900s, but the first case was documented in 1906.

In 1919, major Sinhalese and Tamil political organisations united to form the Ceylon National Congress, under the leadership of Ponnambalam Arunachalam,[110] pressing colonial masters for more constitutional reforms. But without massive popular support, and with the governor's encouragement for "communal representation" by creating a "Colombo seat" that dangled between Sinhalese and Tamils, the Congress lost momentum towards the mid-1920s.[111]

The Donoughmore reforms of 1931 repudiated the communal representation and introduced universal adult franchise (the franchise stood at 4% before the reforms). This step was strongly criticised by the Tamil political leadership, who realised that they would be reduced to a minority in the newly created State Council of Ceylon, which succeeded the legislative council.[112][113] In 1937, Tamil leader G. G. Ponnambalam demanded a 50–50 representation (50% for the Sinhalese and 50% for other ethnic groups) in the State Council. However, this demand was not met by the Soulbury reforms of 1944–45.

Contemporary history

The Soulbury constitution ushered in

S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike was elected prime minister in 1956. His three-year rule had a profound influence through his self-proclaimed role of "defender of the besieged Sinhalese culture".[118] He introduced the controversial Sinhala Only Act, recognising Sinhala as the only official language of the government. Although partially reversed in 1958, the bill posed a grave concern for the Tamil community, which perceived in it a threat to their language and culture.[119][120][121]

The

Queen of Ceylon

Prime Minister

The government of

Lapses in foreign policy resulted in India strengthening the Tigers by providing arms and training.

The 2004 Asian tsunami killed over 30,000 and displaced over 500,000 people in Sri Lanka.[142][143] From 1985 to 2006, the Sri Lankan government and Tamil insurgents held four rounds of peace talks without success. Both LTTE and the government resumed fighting in 2006, and the government officially backed out of the ceasefire in 2008.[121] In 2009, under the Presidency of Mahinda Rajapaksa, the Sri Lanka Armed Forces defeated the LTTE, bringing an end to the civil war on 19 May 2009,[144][145][146][147] and re-established control of the entire country by the Sri Lankan Government.[148] Overall, between 60,000 and 100,000 people were killed during the course of the 26 years of conflict.[149][150]

2019 Sri Lanka Easter bombings carried out by the terrorist group National Thowheeth Jama'ath on 21 April 2019 resulted in the death of 261 innocent people.[151] On 26 April 2019 an anti terrorist operation was carried out against the National Thowheeth Jama'ath by the Sri Lanka Army with the operation being successful and National Thowheeth Jama'ath's insurgency ending.[152][153][154]

Economic troubles in Sri Lanka began in 2019, when a

After winning the 2022 Sri Lankan presidential election, on 21 July 2022, Ranil Wickremesinghe took oath as the ninth President of Sri Lanka.[164] He implemented various economic reforms in efforts to stabilize Sri Lanka's economy.[165]

Geography

Sri Lanka, an island in South Asia shaped as a teardrop or a pear/mango,[166] lies on the Indian Plate, a major tectonic plate that was formerly part of the Indo-Australian Plate.[167] It is in the Indian Ocean southwest of the Bay of Bengal, between latitudes 5° and 10° N, and longitudes 79° and 82° E.[168] Sri Lanka is separated from the mainland portion of the Indian subcontinent by the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Strait. According to Hindu mythology, a land bridge existed between the Indian mainland and Sri Lanka. It now amounts to only a chain of limestone shoals remaining above sea level.[169] Legends claim that it was passable on foot up to 1480 CE, until cyclones deepened the channel.[170][171] Portions are still as shallow as 1 metre (3 ft), hindering navigation.[172] The island consists mostly of flat to rolling coastal plains, with mountains rising only in the south-central part. The highest point is Pidurutalagala, reaching 2,524 metres (8,281 ft) above sea level.

Sri Lanka has 103 rivers. The longest of these is the Mahaweli River, extending 335 kilometres (208 mi).[173] These waterways give rise to 51 natural waterfalls of 10 metres (33 ft) or more. The highest is Bambarakanda Falls, with a height of 263 metres (863 ft).[174] Sri Lanka's coastline is 1,585 km (985 mi) long.[175] Sri Lanka claims an exclusive economic zone extending 200 nautical miles, which is approximately 6.7 times Sri Lanka's land area. The coastline and adjacent waters support highly productive marine ecosystems such as fringing coral reefs and shallow beds of coastal and estuarine seagrasses.[176]

Sri Lanka has 45

Climate

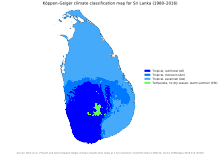

The climate is tropical and warm because of moderating effects of ocean winds. Mean temperatures range from 17 °C (62.6 °F) in the central highlands, where frost may occur for several days in the winter, to a maximum of 33 °C (91.4 °F) in low-altitude areas. Average yearly temperatures range from 28 °C (82.4 °F) to nearly 31 °C (87.8 °F). Day and night temperatures may vary by 14 °C (57.2 °F) to 18 °C (64.4 °F).[181]

The rainfall pattern is influenced by monsoon winds from the Indian Ocean and Bay of Bengal. The "wet zone" and some of the windward slopes of the central highlands receive up to 2,500 millimetres (98.4 in) of rain each year, but the leeward slopes in the east and northeast receive little rain. Most of the east, southeast, and northern parts of Sri Lanka constitute the "dry zone", which receives between 1,200 and 1,900 mm (47 and 75 in) of rain annually.[182]

The arid northwest and southeast coasts receive the least rain at 800 to 1,200 mm (31 to 47 in) per year. Periodic squalls occur and sometimes tropical cyclones bring overcast skies and rains to the southwest, northeast, and eastern parts of the island. Humidity is typically higher in the southwest and mountainous areas and depends on the seasonal patterns of rainfall.[183] An increase in average rainfall coupled with heavier rainfall events has resulted in recurrent flooding and related damages to infrastructure, utility supply and the urban economy.[184]

Flora and fauna

Western Ghats of India and Sri Lanka were included among the first 18 global biodiversity hotspots due to high levels of species endemism. The number of biodiversity hotspots has now increased to 34.[186] Sri Lanka has the highest biodiversity per unit area among Asian countries for flowering plants and all vertebrate groups except birds.[187] A remarkably high proportion of the species among its flora and fauna, 27% of the 3,210 flowering plants and 22% of the mammals, are endemic.[188] Sri Lanka supports a rich avifauna of that stands at 453 species and this include 240 species of birds that are known to breed in the country. 33 species are accepted by some ornithologists as endemic while some ornithologists consider only 27 are endemic and the remaining six are considered as proposed endemics.[189] Sri Lanka's protected areas are administrated by two government bodies; The Department of Forest Conservation and the Department of Wildlife Conservation. Department of Wildlife Conservation administrates 61 wildlife sanctuaries, 22 national parks, four nature reserves, three strict nature reserves, and one jungle corridor while Department of Forest Conservation oversees 65 conservation forests and one national heritage wilderness area. 26.5% of the country's land area is legally protected. This is a higher percentage of protected areas when compared to the rest of Asia.[190]

Sri Lanka contains four terrestrial ecoregions: Sri Lanka lowland rain forests, Sri Lanka montane rain forests, Sri Lanka dry-zone dry evergreen forests, and Deccan thorn scrub forests.[191] Flowering acacias flourish on the arid Jaffna Peninsula. Among the trees of the dry-land forests are valuable species such as satinwood, ebony, ironwood, mahogany and teak. The wet zone is a tropical evergreen forest with tall trees, broad foliage, and a dense undergrowth of vines and creepers. Subtropical evergreen forests resembling those of temperate climates flourish in the higher altitudes.[192]

During the Mahaweli Program of the 1970s and 1980s in northern Sri Lanka, the government set aside four areas of land totalling 1,900 km2 (730 sq mi) as national parks. Statistics of Sri Lanka's forest cover show rapid deforestation from 1956 to 2010. In 1956, 44.2 percent of the country's land area had forest cover. Forest cover depleted rapidly in recent decades; 29.6 percent in 1999, 28.7 percent in 2010.[195]

Government and politics

This section needs expansion with: is missing explication of the constitutional socialist nature of the republic that is reflected in the formal name of the country: "Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka". You can help by adding to it. (July 2022) |

Sri Lanka is a

In common with many democracies, the Sri Lankan government has three branches:

- Executive: The chief executive, and is popularly elected for a five-year term.[198] The president heads the cabinet and appoints ministers from elected members of parliament.[199] The president is immune from legal proceedings while in the office with respect to any acts done or omitted to be done by him or her in either an official or private capacity.[200] Following the passage of the 19th amendment to the constitutionin 2015, the president has two terms, which previously stood at no term limit.

- Legislative: The Parliament of Sri Lanka is a unicameral 225-member legislature with 196 members elected from 22 multi-seat constituencies and 29 elected by proportional representation.[201] Members are elected by universal suffrage for a five-year term. The president may summon, suspend, or end a legislative session and dissolve Parliament at any time after four and a half years. The parliament reserves the power to make all laws.[202] The president's deputy and head of government, the prime minister, leads the ruling party in parliament and shares many executive responsibilities, mainly in domestic affairs.

- Judicial: Sri Lanka's judiciary consists of a Supreme Court – the highest and final superior court of record,[202] a Court of Appeal, High Courts and a number of subordinate courts. The highly complex legal system reflects diverse cultural influences.[203] Criminal law is based almost entirely on British law. Basic civil law derives from Roman-Dutch law. Laws pertaining to marriage, divorce, and inheritance are communal.[204] Because of ancient customary practices and religion, the Sinhala customary law (Kandyan law), the Thesavalamai, and Sharia law are followed in special cases.[205] The president appoints judges to the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, and the High Courts. A judicial service commission, composed of the chief justice and two Supreme Court judges, appoints, transfers, and dismisses lower court judges.

Politics

Sri Lanka junglefowl | |

|---|---|

| Flower | Blue water lily |

| Tree | Ceylon ironwood (nā) |

| Sport | Volleyball |

| Source: [206][207] | |

The current political culture in Sri Lanka is a contest between two rival coalitions led by the centre-left and progressive United People's Freedom Alliance (UPFA), an offspring of Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), and the comparatively right-wing and pro-capitalist United National Party (UNP). after 2018 two major political parties have split with UNP majority has formed Samagi Jana Balawegaya and UPFA majority has formed Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna. The third wing party Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna has gain popularity after 2022.

[208] Sri Lanka is essentially a multi-party democracy with many smaller Buddhist, socialist, and Tamil nationalist political parties. As of July 2011, the number of registered political parties in the country is 67.[209] Of these, the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), established in 1935, is the oldest.[210]

The UNP, established by D. S. Senanayake in 1946, was until recently the largest single political party.[211] It is the only political group which had representation in all parliaments since independence.[211] SLFP was founded by S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike in July 1951.[212] SLFP registered its first victory in 1956, defeating the ruling UNP in the 1956 Parliamentary election.[212] Following the parliamentary election in July 1960, Sirimavo Bandaranaike became the prime minister and the world's first elected female head of government.[213]

President

In 2022, a political crisis started due to the power struggle between President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the Parliament of Sri Lanka. The crisis was fuelled by anti-government protests and demonstrations by the public and also due to the worsening economy of Sri Lanka since 2019. The anti-government sentiment across various parts of Sri Lanka has triggered unprecedented political instability, creating shockwaves in the political arena.[224]

On July 20, 2022, Ranil Wickremesinghe was elected as the ninth President via a parliamentarian election.[225]

Administrative divisions

For administrative purposes, Sri Lanka is divided into nine provinces[226] and twenty-five districts.[227]

Provinces

Provinces in Sri Lanka have existed since the 19th century, but they had no legal status until 1987 when the 13th Amendment of the 1978 constitution established provincial councils after several decades of increasing demand for a decentralisation of the government.[228] Each provincial council is an autonomous body not under the authority of any ministry. Some of its functions had been undertaken by central government ministries, departments, corporations, and statutory authorities,[228] but authority over land and police is not as a rule given to provincial councils.[229][230] Between 1989 and 2006, the Northern and Eastern provinces were temporarily merged to form the North-East Province.[231][232] Prior to 1987, all administrative tasks for the provinces were handled by a district-based civil service which had been in place since colonial times. Now each province is administered by a directly elected provincial council:

|

Districts and local authorities

Each district is administered under a

There are three other types of local authorities: municipal councils (18), urban councils (13) and pradeshiya sabha, also called pradesha sabhai (256).[237] Local authorities were originally based on feudal counties named korale and rata, and were formerly known as "D.R.O. divisions" after the divisional revenue officer.[238] Later, the D.R.O.s became "assistant government agents," and the divisions were known as "A.G.A. divisions". These divisional secretariats are currently administered by a divisional secretary.

Foreign relations

Sri Lanka is a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). While ensuring that it maintains its independence, Sri Lanka has cultivated relations with India.[239] Sri Lanka became a member of the United Nations in 1955. Today, it is also a member of the Commonwealth, the SAARC, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the Asian Development Bank, and the Colombo Plan.

The United National Party has traditionally favoured links with the West, while the Sri Lanka Freedom Party has favoured links with the East.

The Bandaranaike government of 1956 significantly changed the pro-western policies set by the previous UNP government. It recognised Cuba under

Military

The Sri Lanka Armed Forces, comprising the Sri Lanka Army, the Sri Lanka Navy, and the Sri Lanka Air Force, come under the purview of the Ministry of Defence.[254] The total strength of the three services is around 346,000 personnel, with nearly 36,000 reserves.[255] Sri Lanka has not enforced military conscription.[256] Paramilitary units include the Special Task Force, the Civil Security Force, and the Sri Lanka Coast Guard.[257][258]

Since independence in 1948, the primary focus of the armed forces has been internal security, crushing three major insurgencies, two by Marxist militants of the JVP and a 26-year-long conflict with the LTTE. The armed forces have been in a continuous mobilised state for the last 30 years.[259][260] The Sri Lankan Armed Forces have engaged in United Nations peacekeeping operations since the early 1960s, contributing forces to permanent contingents deployed in several UN peacekeeping missions in Chad, Lebanon, and Haiti.[261]

Economy

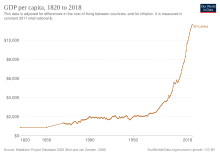

According to the International Monetary Fund, Sri Lanka's

While the production and export of tea, rubber, coffee, sugar, and other commodities remain important, industrialisation has increased the importance of food processing, textiles, telecommunications, and finance. The country's main economic sectors are tourism, tea export, clothing, rice production, and other agricultural products. In addition to these economic sectors, overseas employment, especially in the Middle East, contributes substantially in foreign exchange.[264]

As of 2020[update], the service sector makes up 59.7% of GDP, the industrial sector 26.2%, and the agriculture sector 8.4%.[265] The private sector accounts for 85% of the economy.[266] China, India and the United States are Sri Lanka's largest trading partners.[267] Economic disparities exist between the provinces with the Western Province contributing 45.1% of the GDP and the Southern Province and the Central Province contributing 10.7% and 10%, respectively.[268] With the end of the war, the Northern Province reported a record 22.9% GDP growth in 2010.[269]

The per capita income of Sri Lanka doubled from 2005 to 2011.

The 2011 Global Competitiveness Report, published by the World Economic Forum, described Sri Lanka's economy as transitioning from the factor-driven stage to the efficiency-driven stage and that it ranked 52nd in global competitiveness.[273] Also, out of the 142 countries surveyed, Sri Lanka ranked 45th in health and primary education, 32nd in business sophistication, 42nd in innovation, and 41st in goods market efficiency. In 2016, Sri Lanka ranked 5th in the World Giving Index, registering high levels of contentment and charitable behaviour in its society.[274] In 2010, The New York Times placed Sri Lanka at the top of its list of 31 places to visit.[275] S&P Dow Jones Indices classifies Sri Lanka as a frontier market as of 2018.[276] Sri Lanka ranks well above other South Asian countries in the Human Development Index (HDI) with an index of 0.750.

By 2016, the country's debt soared as it was developing its infrastructure to the point of near bankruptcy which required a bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[277] The IMF had agreed to provide a US$1.5 billion bailout loan in April 2016 after Sri Lanka provided a set of criteria intended to improve its economy. By the fourth quarter of 2016, the debt was estimated to be $64.9 billion. Additional debt had been incurred in the past by state-owned organisations and this was said to be at least $9.5 billion. Since early 2015, domestic debt increased by 12% and external debt by 25%.[278] In November 2016, the IMF reported that the initial disbursement was larger than US$150 million originally planned, a full US$162.6 million (SDR 119.894 million). The agency's evaluation for the first tranche was cautiously optimistic about the future. Under the program, the Sri Lankan government implemented a new Inland Revenue Act and an automatic fuel pricing formula which was noted by the IMF in its fourth review. In 2018 China agreed to bail out Sri Lanka with a loan of $1.25 billion to deal with foreign debt repayment spikes in 2019 to 2021.[279][280][281]

In September 2021, Sri Lanka declared a major

Tourism, which provided the economy with an input of foreign currency, has significantly declined as a result of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.[286]

Transport

Sri Lanka has an extensive road network for inland transportation. With more than 100,000 km (62,000 mi) of paved roads,[287] it has one of the highest road densities in the world (1.5 km or 0.93 mi of paved roads per every 1 km2 or 0.39 sq mi of land). The road network consists of 35 A-Grade highways and four controlled-access highways.[288][289] A and B grade roads are national (arterial) highways administered by Road Development Authority.[290] C and D grade roads are provincial roads coming under the purview of the Provincial Road Development Authority of the respective province. The other roads are local roads falling under local government authorities.

The

Transition to biological agriculture

In June 2021, Sri Lanka imposed a nationwide ban on inorganic fertilisers and pesticides. The program was welcomed by its advisor Vandana Shiva,[292] but ignored critical voices from scientific and farming community who warned about possible collapse of farming,[293][294][295][296][297] including financial crisis due to devaluation of national currency pivoted around tea industry.[293] The situation in the tea industry was described as critical, with farming under the organic program being described as ten times more expensive and producing half of the yield by the farmers.[298] In September 2021 the government declared an economic emergency, as the situation was further aggravated by falling national currency exchange rate, inflation rising as a result of high food prices, and pandemic restrictions in tourism which further decreased country's income.[282]

In November 2021, Sri Lanka abandoned its plan to become the world's first organic farming nation following rising food prices and weeks of protests against the plan.[299] As of December 2021, the damage to agricultural production was already done, with prices having risen substantially for vegetables in Sri Lanka, and time needed to recover from the crisis. The ban on fertiliser has been lifted for certain crops, but the price of urea has risen internationally due to the price for oil and gas.[286] Jeevika Weerahewa, a senior lecturer at the University of Peradeniya, predicted that the ban would reduce the paddy harvest in 2022 by an unprecedented 50%.[300]

Demographics

Sri Lanka has roughly 22,156,000 people and an annual population growth rate of 0.5%. The

Largest cities

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Colombo  Kaduwela |

1 | Colombo | Western | 561,314 | 11 | Galle | Southern | 86,333 | |

| 2 | Kaduwela | Western | 252,041 | 12 | Batticaloa | Eastern | 86,227 | ||

| 3 | Maharagama | Western | 196,423 | 13 | Jaffna | Northern | 80,829 | ||

| 4 | Kesbewa | Western | 185,122 | 14 | Matara | Southern | 74,193 | ||

| 5 | Dehiwala-Mount Lavinia | Western | 184,468 | 15 | Gampaha | Western | 62,335 | ||

| 6 | Moratuwa | Western | 168,280 | 16 | Katunayake | Western | 60,915 | ||

| 7 | Negombo | Western | 142,449 | 17 | Boralesgamuwa | Western | 60,110 | ||

| 8 | Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte | Western | 107,925 | 18 | Kolonnawa | Western | 60,044 | ||

| 9 | Kalmunai | Eastern | 99,893 | 19 | Anuradhapura | North Central | 50,595 | ||

| 10 | Kandy | Central | 98,828 | 20 | Trincomalee | Eastern | 48,351 | ||

Languages

Religion

Although

Christianity reached the country at least as early as the fifth century (and possibly in the first),[317] gaining a wider foothold through Western colonists who began to arrive early in the 16th century.[318] Around 7.4% of the Sri Lankan population are Christians, of whom 82% are Roman Catholics who trace their religious heritage directly to the Portuguese. Tamil Catholics attribute their religious heritage to St. Francis Xavier as well as Portuguese missionaries. The remaining Christians are evenly split between the Anglican Church of Ceylon and other Protestant denominations.[319]

There is also a small population of

Religion plays a prominent role in the life and culture of Sri Lankans. The

Health

Sri Lankans have a life expectancy of 75.5 years at birth, which is 10% higher than the world average.[265][264] The infant mortality rate stands at 8.5 per 1,000 births and the maternal mortality rate at 0.39 per 1,000 births, which is on par with figures from developed countries. The universal "pro-poor"[323] health care system adopted by the country has contributed much towards these figures.[324] Sri Lanka ranks first among southeast Asian countries with respect to deaths by suicide, with 33 deaths per 100,000 persons. According to the Department of Census and Statistics, poverty, destructive pastimes, and inability to cope with stressful situations are the main causes behind the high suicide rates.[325] On 8 July 2020, the World Health Organization declared that Sri Lanka had successfully eliminated rubella and measles ahead of their 2023 target.[326]

Education

With a

The free education system established in 1945[331] is a result of the initiative of C. W. W. Kannangara and A. Ratnayake.[332][333] It is one of the few countries in the world that provide universal free education from primary to tertiary stage.[334] Kannangara led the establishment of the Madhya Vidyalayas (central schools) in different parts of the country in order to provide education to Sri Lanka's rural children.[329] In 1942, a special education committee proposed extensive reforms to establish an efficient and quality education system for the people. However, in the 1980s changes to this system separated the administration of schools between the central government and the provincial government. Thus the elite national schools are controlled directly by the ministry of education and the provincial schools by the provincial government. Sri Lanka has approximately 10,155 government schools, 120 private schools and 802 pirivenas.[265]

Sri Lanka has 17 public universities.[335][336] A lack of responsiveness of the education system to labour market requirements, disparities in access to quality education, lack of an effective linkage between secondary and tertiary education remain major challenges for the education sector.[337] A number of private, degree awarding institutions have emerged in recent times to fill in these gaps, yet the participation at tertiary level education remains at 5.1%.[338] Sri Lanka was ranked 90th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[339][340]

Human rights and media

The Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (formerly Radio Ceylon) is the oldest-running radio station in Asia,[341] established in 1923 by Edward Harper just three years after broadcasting began in Europe.[341] The station broadcasts services in Sinhala, Tamil, English and Hindi. Since the 1980s, many private radio stations have also been introduced. Broadcast television was introduced in 1979 when the Independent Television Network was launched. Initially, all television stations were state-controlled, but private television networks began broadcasting in 1992.[342]

As of 2020[update], 192 newspapers (122 Sinhala, 24 Tamil, 43 English, 3 multilingual) are published and 25 TV stations and 58 radio stations are in operation.

Officially, the constitution of Sri Lanka guarantees human rights as ratified by the United Nations. However, several groups, such as

The UN Human Rights Council has documented over 12,000 named individuals who have disappeared after detention by security forces in Sri Lanka, the second-highest figure in the world since the Working Group came into being in 1980.[354] The Sri Lankan government confirmed that 6,445 of these died. Allegations of human rights abuses have not ended with the close of the ethnic conflict.[355]

In 2012, the UK charity Freedom from Torture reported that it had received 233 referrals of torture survivors from Sri Lanka for clinical treatment or other services provided by the charity. In the same year, the group published Out of the Silence, which documents evidence of torture in Sri Lanka and demonstrates that the practice has continued long after the end of the civil war in 2009.[358] On 29 July 2020, Human Rights Watch said that the Sri Lanka government has targeted lawyers, human rights defenders, and journalists to suppress criticism against the government.[359]

Culture

The culture of Sri Lanka is influenced primarily by Buddhism and Hinduism.[360] Sri Lanka is the home to two main traditional cultures: the Sinhalese (centred in Kandy and Anuradhapura) and the Tamil (centred in Jaffna). Tamils co-existed with the Sinhalese people since then, and the early mixing rendered the two ethnic groups almost physically indistinguishable.[361] Ancient Sri Lanka is marked for its genius in hydraulic engineering and architecture. The British colonial culture has also influenced the locals. The rich cultural traditions shared by all Sri Lankan cultures is the basis of the country's long life expectancy, advanced health standards, and high literacy rate.[362]

Food and festivals

Dishes include rice and curry,

In April, Sri Lankans celebrate the

.Visual, literary and performing arts

The movie

An influential filmmaker is

The earliest music in Sri Lanka came from theatrical performances such as Kolam, Sokari and Nadagam.

There are three main styles of Sri Lankan classical dance. They are, the

The history of Sri Lankan painting and sculpture can be traced as far back as to the 2nd or 3rd century BCE.[375] The earliest mention about the art of painting on Mahāvaṃsa, is to the drawing of a palace on cloth using cinnabar in the 2nd century BCE. The chronicles have a description of various paintings in relic chambers of Buddhist stupas and in monastic residences.

Theatre came to the country when a Parsi theatre company from Mumbai introduced Nurti, a blend of European and Indian theatrical conventions to the Colombo audience in the 19th century.[373] The golden age of Sri Lankan drama and theatre began with the staging of Maname, a play written by Ediriweera Sarachchandra in 1956.[376] It was followed by a series of popular dramas like Sinhabāhu, Pabāvatī, Mahāsāra, Muudu Puththu and Subha saha Yasa.

Sri Lankan literature spans at least two millennia and is heir to the

Sport

While the national sport is volleyball, by far the most popular sport in the country is Cricket.[380] Rugby union also enjoys extensive popularity,[381] as do association football, netball and tennis. Aquatic sports such as boating, surfing, swimming, kitesurfing[382] and scuba diving attract many Sri Lankans and foreign tourists. There are two styles of martial arts native to Sri Lanka: Cheena di and Angampora.[383]

The

Sri Lankans have won two medals at Olympic Games: one silver, by Duncan White at the 1948 London Olympics for men's 400 metres hurdles;[399] and one silver by Susanthika Jayasinghe at the 2000 Sydney Olympics for women's 200 metres.[400] In 1973, Muhammad Lafir won the World Billiards Championship, the highest feat by a Sri Lankan in a Cue sport.[401] Sri Lanka has also won the Carrom World Championship titles twice in 2012, 2016[402] and 2018, the men's team becoming champions and the women's team winning second place. The Sri Lankan National Badminton Championships was annually held between 1953 and 2011.

Sri Lanka national football team also won the prestigious 1995 South Asian Gold Cup.[403][404][405][406][407]

See also

Notes

- ^ UK: /sri ˈlæŋkə, ʃriː -/, US: /- ˈlɑːŋkə/ ⓘ; Sinhala: ශ්රී ලංකා, romanized: Śrī Laṅkā (IPA: [ʃriː laŋkaː]); Tamil: இலங்கை, romanized: Ilaṅkai (IPA: [ilaŋɡaj])

References

Citations

- ^ "Sri Jayewardenepura Kotte". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "Colombo". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "Official Languages Policy". languagesdept.gov.lk. Department of Official Languages. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- CIA. 22 September 2021. Archivedfrom the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "2018 Report on International Religious Freedom: Sri Lanka". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Constitution of Sri Lanka" (PDF). Parliament of Sri Lanka. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-19-561655-2. A History of Sri Lanka.

- ^ "Mid-year Population Estimates by District & Sex, 2014 - 2023". statistics.gov.lk. Department of Census and Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing 2011 Enumeration Stage February–March 2012" (PDF). Department of Census and Statistics – Sri Lanka. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2022". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. October 2022. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Gini Index". World Bank. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Vedda". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-971-561-607-2.

- ISBN 978-0-671-04188-5.

... the Pali canon of Theravada is the earliest known collection of Buddhist writings ...

- ^ "Religions – Buddhism: Theravada Buddhism". BBC. 2 October 2002. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ISBN 978-955-9043-02-7.

- ^ British Prime Minister Winston Churchill described the moment a Japanese fleet prepared to invade Sri Lanka as "the most dangerous and distressing moment of the entire conflict". – Commonwealth Air Training Program Museum, The Saviour of Ceylon Archived 22 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "A Brief History of Sri Lanka". localhistories.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Reuters Sri Lanka wins civil war, says kills rebel leader Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine Reuters (18 May 2009). Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Ellis-Petersen, Hannah (9 April 2022). "'We're finished': Sri Lankans pushed to the brink by financial crisis". The Observer. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-7614-1477-3.

- ISBN 978-81-206-1271-6.

- ISBN 978-1-57958-470-2. Archivedfrom the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-136-31188-8.

- ISBN 978-0-231-51524-5.

- ^ Abeydeera, Ananda. "In Search of Taprobane: the Western discovery and mapping of Ceylon". Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Hobson-Jobson". Dsalsrv02.uchicago.edu. 1 September 2001. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Serendipity – definition of serendipity by The Free Dictionary". Thefreedictionary.com. 10 November 2017. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ Rajasingham, K. T. (11 August 2001). "Sri Lanka: The untold story". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 14 August 2001. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Zubair, Lareef. "Etymologies of Lanka, Serendib, Taprobane and Ceylon". Archived from the original on 22 April 2007.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka" (PDF). University of Minnesota Human Rights Library. 7 September 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Chapter I – The People, The State And Sovereignty". The Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Haviland, Charles (1 January 2011). "Sri Lanka erases colonial name, Ceylon". BBC. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Deraniyagala, Siran U. "Pre and Protohistoric settlement in Sri Lanka". International Union of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences. XIII U. I. S. P. P. Congress Proceedings – Forli, 8–14 September 1996. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Pahiyangala (Fa-Hiengala) Caves". angelfire.com. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Kennedy, Kenneth A.R., Disotell, T.W., Roertgen, J., Chiment, J., Sherry, J. Ancient Ceylon 6: Biological anthropology of upper Pleistocene hominids from Sri Lanka: Batadomba Lena and Beli Lena caves. pp. 165–265.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ De Silva 1981, pp. 6–7

- ISBN 978-955-9159-00-1.

- ^ Deraniyagala, S.U. "Early Man and the Rise of Civilisation in Sri Lanka: the Archaeological Evidence". lankalibrary.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Reading the past in a more inclusive way – Interview with Dr. Sudharshan Seneviratne". Frontline (2006). 26 January 2006. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ a b Seneviratne, Sudharshan (1984). Social base of early Buddhism in south east India and Sri Lanka.

- ^ Karunaratne, Priyantha (2010). Secondary state formation during the early iron age on the island of Sri Lanka : the evolution of a periphery.

- ^ Robin Conningham – Anuradhapura – The British-Sri Lankan Excavations at Anuradhapura Salgaha Watta Volumes 1 and 2 (1999/2006)

- ^ Seneviratne, Sudarshan (1989). "Pre-state chieftains and servants of the state: a case study of Parumaka". The Sri Lanka Journal of the Humanities. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ISBN 978-81-208-0545-3.

- ISBN 978-81-206-0208-3.

- ^ "The Coming of Vijaya". The Mahavamsa. 8 October 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ "Vijaya (Singha) and the Lankan Monarchs – Family #3000". Ancestry.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "The Consecrating of Vijaya". Mahavamsa. 8 October 2011. Archived from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "World Heritage site: Anuradhapura". worldheritagesite.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2004. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Waterworld: Ancient Sinhalese Irrigation". mysrilankaholidays.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Perera H. R. "Buddhism in Sri Lanka: A Short History". accesstoinsight.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-5459-6.

- ^ Mahavamsa. 28 May 2008. Archivedfrom the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Buddhism in Sri Lanka". buddhanet.net. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Paw, p. 6

- ^ Gunawardana, Jagath. "Historical trees: Overlooked aspect of heritage that needs a revival of interest". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ISBN 9780198542575. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 200.

- ^ "The History of Ceylon". sltda.gov.lk. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-9873451-1-0.

- ISBN 978-955-613-111-6.

- ISBN 978-0-7069-7621-2. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ Codrington, Ch. 4 Archived 7 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lambert, Tim. "A Brief History of Sri Lanka". localhistories.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- JSTOR 1522637.

- ^ "Ancient Irrigation Works". lakdiva.org. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-55369-793-0. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

Parakramabahu 1 further extended the system to the highest resplendent peak of hydraulic civilization of the country's history.

- ^ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland: Volume 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for the Royal Asiatic Society. 1875. p. 152. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

... and when at the height of its prosperity, during the long and glorious reign of Parakramabahu the Great ...

- ^ Beveridge, H. (1894). "The Site of Karna Suvarna". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 62: 324. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 29 September 2020 – via Google Books.

His [Parakramabahu's] reign is described by Tumour as having been the most martial, enterprising, and glorious in Singhalese history.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55369-793-0. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ "Parakrama Samudra". International Lake Environment Committee. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- ^ "ParakramaBahu I: 1153–1186". lakdiva.org. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014.

- ISBN 978-81-7003-148-2. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

..His invasion in 1215 was more or less a looting expedition..

- ^ a b Nadarajan, V History of Ceylon Tamils, p. 72

- ^ a b Indrapala, K Early Tamil Settlements in Ceylon, p. 16

- ISBN 978-81-206-1686-8. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-19-506418-6. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ Codrington, Ch. 6 Archived 10 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ India's interaction with Southeast Asia, by Govind Chandra Pande p.286

- ^ Craig J. Reynolds (2019). Power, Protection and Magic in Thailand: The Cosmos of a Southern Policeman. ANU Press. pp. 74–75.

- ^ "Astronesians Historical and Comparative Perspectives" Page 146 Archived 24 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine "Annual trade between China and India through the Malacca Straits had opened by about 200 BCE. Perhaps by that time Austronesian sailors were regularly carrying cloves and cinnamon to India and Sri Lanka, and perhaps even as far as the coast of Africa in boats with outriggers. Certainly they have left numerous traces in canoe design, rigs, outriggers and fishing techniques, and a mention in Greek literature (Christie 1957)."

- ^ "South East Aisa in Ming Shi-lu". Geoff Wade, 2005. Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ "Voyages of Zheng He 1405–1433". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 18 December 2007. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ "Ming Voyages". Columbia University. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ "Admiral Zheng He". aramco world. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ "The trilingual inscription of Admiral Zheng He". lankalibrary forum. Archived from the original on 20 June 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ "Zheng He". world heritage site. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ "Sri Lanka History". Thondaman Foundation. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ "King Wimaladharmasuriya". S.B. Karalliyadde – The Island. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Knox, Robert (1681). An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon. London: Reprint. Asian Educational Services. pp. 19–47.

- ISBN 978-81-206-1845-9.

- ISBN 978-0-89680-261-2. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b c "A kingdom is born, a kingdom is lost". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-472-10288-4. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ Codrington, Ch. 9 Archived 13 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The first British occupation and the definitive Dutch surrender". colonialvoyage.com. 18 February 2014. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ a b c "History of Sri Lanka and significant World events from 1796 AD to 1948". scenicsrilanka.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Codrington, Ch. 11 Archived 21 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Keppetipola and the Uva Rebellion". lankalibrary.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7619-3278-9.

- ^ a b Nubin 2002, p. 115

- ^ "Gongale Goda Banda (1809–1849) : The leader of the 1848 rebellion". Wimalaratne, K.D.G. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-7146-2019-0. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Nubin 2002, pp. 116–117

- ISBN 978-81-208-1047-1. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Cutting edge of Hindu revivalism in Jaffna". Balachandran, P.K. 25 June 2006. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ De Silva 1981, p. 387

- ^ De Silva 1981, p. 386

- ^ De Silva 1981, pp. 389–395

- ^ a b "Chronology of events related to Tamils in Sri Lanka (1500–1948)". Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar. National University of Malaysia. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ De Silva 1981, p. 423

- ^ "Sinhalese Parties". Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Sinhalese Parties". Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Nubin 2002, pp. 121–122

- ^ Weerakoon, Batty. "Bandaranaike and Hartal of 1953". The Island. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Nubin 2002, p. 123

- ISBN 978-0-262-52333-2. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-415-22905-0. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b c "Sri Lanka Profile". BBC News. 5 November 2013. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33205-0. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Staff profile: Jonathan Spencer". University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Sri Lanka: The untold story – Assassination of Bandaranaike". Rajasingham, K. T. 2002. Archived from the original on 20 December 2001. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Nubin 2002, pp. 128–129

- ^ De Silva; K. M. (July 1997). "Affirmative Action Policies: The Sri Lankan Experience" (PDF). International Centre for Ethnic Studies. pp. 248–254. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011.

- OCLC 7925123.

- ^ Taraki Sivaram (May 1994). "The Exclusive Right to Write Eelam History". Tamil Nation. Archived from the original on 19 November 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-231-12699-1. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ Rohan Gunaratna (December 1998). "International and Regional Implications of the Sri Lankan Tamil Insurgency" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Rajasingham, K.T. (2002). "Tamil militancy – a manifestation". Archived from the original on 13 February 2002. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b "Sri Lanka – an Overview". Fulbright commission. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ^ "Remembering Sri Lanka's Black July – BBC News". BBC News. 23 July 2013. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "The Black July 1983 that Created a Collective Trauma". Jayatunge, Ruwan M. LankaWeb. 2010. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "LTTE: the Indian connection". Sunday Times. 1997. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Uppermost in our minds was to save the Gandhis' name". Express India. 1997. Archived from the original on 11 August 2007.

- ^ "For firmer and finer International Relations". Wijesinghe, Sarath. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- .

- ISBN 978-955-8093-00-9. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ a b "Chapter 30: Whirlpool of violence, Sri Lanka: The Untold Story". Asia Times. 2002. Archived from the original on 16 April 2002. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "1990, The War Year if Ethnic Cleansing of the Muslims From North and the East of Sri Lanka". lankanewspapers.com. 2008. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ "US presidents in tsunami aid plea". BBC News. 3 January 2005. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ "One year after the tsunami, Sri Lankan survivors still live in squalour". World Socialist Web Site. 29 December 2005. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ Weaver, Matthew; Chamberlain, Gethin (19 May 2009). "Sri Lanka declares end to war with Tamil Tigers". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ McDonald, Mark (25 May 2009). "Tamil Tigers Confirm Death of Their Leader". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Tamil Tigers confirm leader's death". Al Jazeera English. 24 May 2009. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "Tamil Tigers admit leader is dead". BBC News. 24 May 2009. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ Weaver, Matthew; Chamberlain, Gethin (19 May 2009). "Sri Lanka declares end to war with Tamil Tigers". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "Up to 100,000 killed in Sri Lanka's civil war: UN". ABC Australia. 20 May 2009. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Olsen, Erik. "Sri Lanka". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Easter Sunday massacres: Where do we go from here?". Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ "Wife, daughter of Sri Lanka bombings mastermind will survive blast:..." Reuters. 29 April 2019. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "15 bodies including children found at blast site in Sainthamaruthu". adaderana.lk. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ "15 bodies found from site of shootout and explosions in Saindamaradu;6 Suicide bombers among them". Hiru News. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ "Everything to Know About Sri Lanka's Economic Crisis". BORGEN. 23 April 2022. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ "Sri Lanka declares worst economic downturn in 73 years". France 24. 30 April 2021. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Sri Lanka declares food emergency as forex crisis worsens". India Today. Agence France-Presse. 31 August 2021. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Sri Lanka's PM says its debt-laden economy has 'collapsed'". Sky News. Archived from the original on 22 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Sri Lanka becomes first Asia-Pacific country in decades to default on foreign debt". NewsWire. 19 May 2022. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Sri Lanka to reduce power cut duration from April 18 as rains start – PUCSL". EconomyNext. 11 April 2022. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Sri Lanka protesters break into President's House as thousands rally". CNN. 9 July 2022. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "President Gotabaya Rajapaksa Resigns – letter sent to Speaker of Parliament". Hiru News. 14 July 2022. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "Sri Lankan crisis: Protesters set PM Ranil Wickremesinghe's residence on fire". Hindustan Times News. 9 July 2022. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Ranil Wickremesinghe takes oath as President of Sri Lanka". indiatoday.in. 21 July 2022. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ "Sri Lanka cuts policy rates to reduce inflation and boost economic recovery". The Hindu. June 2023. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- ISBN 9789812040602. Archivedfrom the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ Seth Stein. "The January 26, 2001 Bhuj Earthquake and the Diffuse Western Boundary of the Indian Plate" (PDF). earth.northwestern.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ "Geographic Coordinates for Sri Lanka Towns and Villages". jyotisha.00it.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Gods row minister offers to quit". BBC. 15 September 2007. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- ISBN 978-81-261-3489-2.

- ^ "Ramar Sethu, a world heritage centre?". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Adam's Bridge". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-903471-78-4.

- ^ "Introducing Sri Lanka". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Depletion of coastal resources" (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. p. 86. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012.

- ^ "5 Coral Reefs of Sri Lanka: Current Status And Resource Management". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Information Brief on Mangroves in Sri Lanka". International Union for Conservation of Nature. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Sri Lanka Graphite Production by Year". indexmundi.com. 2009. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Availability of sizeable deposits of thorium in Sri Lanka". Tissa Vitharana. 2008. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Three Dimensional Seismic Survey for Oil Exploration in Block SL-2007-01-001 in Gulf of Mannar–Sri Lanka" (PDF). Cairn Lanka. 2009. pp. iv–vii. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Climate & Seasons: Sri Lanka". mysrilanka.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Sri Lanka Rainfall". mysrilanka.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Sri Lanka Climate Guide". climatetemp.info. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012.

- ^ Integrating urban agriculture and forestry into climate change action plans: Lessons from Sri Lanka Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Marielle Dubbeling, the RUAF Foundation, 2014

- ^ "Sri Lanka Survey Finds More Elephants Than Expected". Voice of America. 2 September 2011. Archived from the original on 29 January 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Gunawardene, N. R.; Daniels, A. E. D.; Gunatilleke, I. A. U. N.; Gunatilleke, C. V. S.; Karunakaran, P. V.; Nayak, K.; Prasad, S.; Puyravaud, P.; Ramesh, B. R.; Subramanian, K. A; Vasanthy, G. (10 December 2007). "A brief overview of the Western Ghats—Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot" (PDF). Current Science. 93 (11): 1567–1572. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ISBN 2-8317-0643-2. Archived(PDF) from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "An interview with Dr. Ranil Senanayake, chairman of Rainforest Rescue International". news.mongabay.com. Archived from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-955-0-03355-3. Archived(PDF) from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- S2CID 58915438.

- PMID 28608869.

- ^ "Forests, Grasslands, and Drylands – Sri Lanka" (PDF). p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2007.

- ^ "Sri Lanka". UNESCO. 1 September 2006. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ^ "Minneriya National Park". trabanatours.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Chapter 1 – The People, The State and Sovereignty". The Official Website of the Government of Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-07-243298-5.

- ^ "The Executive Presidency". The Official Website of the Government of Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "The Constitution of Sri Lanka – Contents". The Official Website of the Government of Sri Lanka. 20 November 2003. Archived from the original on 18 November 2014.

- ^ "Presidential Immunity". constitution.lk.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Evolution of the Parliamentary System". Parliament of Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b "The Legislative Power of Parliament". Parliament of Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010.

- United Nations Public Administration Network. p. 2. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Background Note: Sri Lanka". U.S. Department of State. United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Sri Lanka Society & Culture: Customs, Rituals & Traditions". lankalibrary.com. Archived from the original on 18 June 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "National Symbols of Sri Lanka". My Sri Lanka. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ^ "Sri Lanka names its national butterfly". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ^ Nubin 2002, p. 95

- ^ "Political Parties in Sri Lanka". Department of Election, Sri Lanka. July 2011. Archived from the original on 19 September 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ "Sri Lanka's oldest political party". Daily News. 18 December 2010. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ a b "UNP: The Story of the Major Tradition". unplanka.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Charting a new course for Sri Lanka's success". Daily News. 16 November 2009. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ "Ceylon chooses world's first woman PM". BBC. 20 July 1960. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Society of Jesus in India (1946). New review, Volume 23. India: Macmillan and co. ltd. p. 78. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-56072-784-2. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b c "Sri Lanka: Post Colonial History". Lanka Library. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Sri Lanka Tamil National Alliance denies having talks with Buddhist prelates". Asian Tribune. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ "Revolutionary Idealism and Parliamentary Politics" (PDF). Asia-Pacific Journal of Social Sciences. December 2010. p. 139. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2011.

- ^ "Sri Lankan Muslims: Between ethno-nationalism and the global ummah". Dennis B. McGilvray. Association for the Study of Ethnicity and Nationalism. January 2011. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "Sri Lanka President Sirisena abandons re-election bid". The Straits Times. 6 October 2019. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "Sri Lanka's ruling party calls an election, hoping for a landslide". The Economist. 5 March 2020. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Bastians, Dharisha; Schultz, Kai (17 November 2019). "Gotabaya Rajapaksa Wins Sri Lanka Presidential Election". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "Mahinda Rajapaksa sworn in as Sri Lanka's PM". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "Rajapaksa Clan Losing Grip on Power in Sri Lanka". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ Jayasinghe, Uditha; Pal, Alasdair; Ghoshal, Devjyot (21 July 2022). "Sri Lanka gets new president in six-time PM Wickremesinghe". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ "The Constitution of Sri Lanka – Eighth Schedule". Priu.gov.lk. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "The Constitution of Sri Lanka – First Schedule". Priu.gov.lk. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Provincial Councils". The Official Website of the Government of Sri Lanka. 3 September 2010. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009.

- ^ "Lanka heads for collision course with India: Report". The Indian Express. 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Accepting reality and building trust". Jehan Perera. peace-srilanka.org. 14 September 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2010.

- ^ "North-East merger illegal: SC". LankaNewspapers.com. 17 October 2006. Archived from the original on 24 May 2009.

- ^ "North East De-merger-At What Cost? Update No. 107". Hariharan, R. southasiaanalysis.org. 19 October 2010. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing Sri Lanka 2012" (PDF). Department of Census and Statistics. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "Provincial Gross Domestic Product (PGDP) - 2022" (PDF). cbsl.gov.lk. Central Bank of Sri Lanka. 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Sri Lanka Prosperity Index - 2021" (PDF). cbsl.gov.lk. Central Bank of Sri Lanka. 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ "List of Codes for the Administrative Divisions of Sri Lanka 2001" (PDF). Department of Census and Statistics. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-9542917-9-2. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2018.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ISBN 978-0-521-02975-9. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ a b "Foreign Relations". Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Jayasekera, Upali S. "Colombo Plan at 57". Colombo Plan. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012.

- ^ "Sri Lanka excels at the San Francisco Peace Conference" (PDF). The Island. 7 September 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ "Lanka-China bilateral ties at its zenith". The Sunday Observer. 3 October 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Bandung Conference of 1955 and the resurgence of Asia and Africa". The Daily News. 21 April 2005. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ "Lanka-Cuba relations should be strengthened". The Daily News. 14 January 2004. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ "29 October 1964". Pact.lk. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Statelessness abolished?". cope.nu. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Suryanarayan, V. (22 August 2011). "India-Sri Lanka: 1921 Conference On Fisheries And Ceding Of Kachchatheevu – Analysis". Albany Tribune. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012.

- ^ "NAM Golden Jubilee this year". The Sunday Observer. 10 July 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- S2CID 154512767.

- ^ Weisman, Steven R. (5 June 1987). "India airlifts aid to Tamil rebels". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ "Sri Lanka: Background and U.S. Relations" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Russia and Sri Lanka to strengthen bilateral relations". Asian Tribune. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "World leaders send warm greeting to Sri Lanka on Independence Day". Asian Tribune. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: Sr Lanka". Central Intelligence Agency. 16 August 2011. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-85743-557-3.

- ^ "Conscription (most recent) by country". NationMaster. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ "Sri Lanka coast guard sets up bases". Lanka Business Online. 10 August 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Coast Guard bill passed in Parliament". Sri Lanka Ministry of Defence. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ "How Sri Lanka's military won". BBC News. 22 May 2009. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Doucet, Lyse (13 November 2012). "UN 'failed Sri Lanka civilians', says internal probe". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ "UN Mission's Summary detailed by Country – March 2012" (PDF). United Nations. April 2012. p. 33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Fernando, Maxwell. "Echoes of a Plantation Economy". historyofceylontea.com. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012.

- ^ "The Strategic Importance of Sri Lanka to Australia". asiapacificdefencereporter.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b c "Annual Report 2010". Ministry of Finance – Sri Lanka. 2011. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Ministry of Finance. Archivedfrom the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Country Partnership Strategy" (PDF). Asian Development Bank. 2008. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Sri Lanka's Top Trading Partners". Lakshman Kadiragamar Institute. 2018. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ "Western Province share of national GDP falling: CB". Sunday Times. 17 July 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ "Sri Lanka's Northern province has recorded the highest GDP growth rate of 22.9 per cent last year". Asian Tribune. 18 July 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ "Sri Lanka Tea Board". worldteanews.com. Retrieved 7 September 2011.[dead link]

- ^ "Per capita income has doubled". tops.lk. 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ "Inequality drops with poverty" (PDF). Department of Census and Statistics. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Schwab, Klaus (2011). The Global Competitiveness Report 2011–2012 (PDF) (Report). World Economic Forum. pp. 326–327. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "CAF world giving index 2016" (PDF). cafonline.org. Charities aid foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "The 31 Places to Go in 2010". The New York Times. 24 January 2010. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ "A Closer Look at Indices Country Classifications – Indexology® Blog | S&P Dow Jones Indices". Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Shaffer, Leslie (2 May 2016). "Why Sri Lanka's economic outlook is looking less rosy". CNBC. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

While the government is aiming to raise its low revenue collection, partly through an increase in the value-added tax rate ... the country has a spotty record on tax collection.

- ^ Shepard, Wade (30 September 2016). "Sri Lanka's Debt Crisis Is So Bad The Government Doesn't Even Know How Much Money It Owes". Forbes. Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

"We still don't know the exact total debt number," Sri Lanka's prime minister admitted to parliament earlier this month.

- ^ "IMF Completes First Review of the Extended Arrangement Under the EFF with Sri Lanka and Approves US$162.6 Million Disbursement". IMF. 18 November 2016. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

[IMF] completed the first review of Sri Lanka's economic performance under the program supported by a three-year extended arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) arrangement.

- ^ "Sri Lanka : 2018 Article IV Consultation and the Fourth Review Under the Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Sri Lanka". IMF. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.