Stereoselectivity

In

An enantioselective reaction is one in which one enantiomer is formed in preference to the other, in a reaction that creates an optically active product from an achiral starting material, using either a chiral catalyst, an enzyme or a chiral reagent. The degree of selectivity is measured by the enantiomeric excess. An important variant is kinetic resolution, in which a pre-existing chiral center undergoes reaction with a chiral catalyst, an enzyme or a chiral reagent such that one enantiomer reacts faster than the other and leaves behind the less reactive enantiomer, or in which a pre-existing chiral center influences the reactivity of a reaction center elsewhere in the same molecule.

A diastereoselective reaction is one in which one

Stereoconvergence can be considered an opposite of stereospecificity, when the reaction of two different stereoisomers yield a single product stereoisomer.

The quality of stereoselectivity is concerned solely with the products, and their stereochemistry. Of a number of possible stereoisomeric products, the reaction selects one or two to be formed.

Stereomutation is a general term for the conversion of one stereoisomer into another. For example, racemization (as in SN1 reactions), epimerization (as in interconversion of D-glucose and D-mannose in Lobry de Bruyn–Van Ekenstein transformation), or asymmetric transformation (conversion of a racemate into a pure enantiomer or into a mixture in which one enantiomer is present in excess, or of a diastereoisomeric mixture into a single diastereoisomer or into a mixture in which one diastereoisomer predominates).[4]

Examples

An example of modest stereoselectivity is the

The

With a

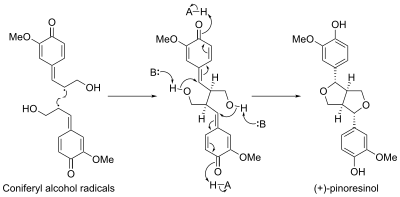

Stereoselective biosynthesis

See also

Notes and references

- ^ (a)"Overlap Control of Carbanionoid Reactions. I. Stereoselectivity in Alkaline Epoxidation," Zimmerman, H. E.; Singer, L.; Thyagarajan, B. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1959, 81, 108-116. (b)Eliel, E., "Stereochemistry of Carbon Compound", McGraw-Hill, 1962 pp 434-436.

- ^ For instance, the SN1 reaction destroys a pre-existing stereocenter, and then creates a new one.

- ^ Or fewer than all possible relative stereochemistries are obtained.

- ^ Eliel, E.L. & Willen S.H., "Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds", John Wiley & Sons, 2008 pp 1209.

- ^ Effects of base strength and size upon in base-promoted elimination reactions. Richard A. Bartsch, Gerald M. Pruss, Bruce A. Bushaw, Karl E. Wiegers

- ^ Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 10, p.140 (2004); Vol. 77, p.78 (2000). Link

- ^ Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 10, p.603 (2004); Vol. 79, p.93 (2002).Link

- S2CID 41957412.

- S2CID 195313754.