Stomach cancer

| Stomach cancer | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Gastric cancer |

| Diagnostic method | Biopsy done during endoscopy[1] |

| Prevention | Mediterranean diet, not smoking[2][5] |

| Treatment | Surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy[1] |

| Prognosis | Five-year survival rate: < 10% (advanced cases),[6] 32% (US),[7] 71% (Japan)[8] |

| Frequency | 968,350 (2022)[9] |

| Deaths | 659,853 (2022)[9] |

Stomach cancer, also known as gastric cancer, is a

The most common cause is infection by the

A Mediterranean diet lowers the risk of stomach cancer, as does not smoking.[2][5] Tentative evidence indicates that treating H. pylori decreases the future risk.[2][5] If stomach cancer is treated early, it can be cured.[2] Treatments may include some combination of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and targeted therapy.[1][13] For certain subtypes of gastric cancer, cancer immunotherapy is an option as well.[14] If treated late, palliative care may be advised.[2] Some types of lymphoma can be cured by eliminating H. pylori.[15] Outcomes are often poor, with a less than 10% five-year survival rate in the Western world for advanced cases.[6] This is largely because most people with the condition present with advanced disease.[6] In the United States, five-year survival is 31.5%,[7] while in South Korea it is over 65% and Japan over 70%, partly due to screening efforts.[2][8]

Globally, stomach cancer is the fifth-leading type of cancer and the third-leading cause of death from cancer, making up 7% of cases and 9% of deaths.

Signs and symptoms

Stomach cancer is often either

Early cancers may be associated with

Gastric cancers that have enlarged and invaded normal tissue can cause

These can be symptoms of other problems such as a

Risk factors

Gastric cancer can occur as a result of many factors.[27] It occurs twice as commonly in males as females. Estrogen may protect women against the development of this form of cancer.[28][29]

Infections

Smoking

Smoking increases the risk of developing gastric cancer significantly, from 40% increased risk for current smokers to 82% increase for heavy smokers. Gastric cancers due to smoking mostly occur in the upper part of the stomach near the esophagus.[34][35][36]

Alcohol

Some studies show increased risk with alcohol consumption as well.[4][37]

Diet

Dietary factors are not proven causes, and the association between stomach cancer and various foods and beverages is weak.

Fresh fruit and vegetable intake,[44] citrus fruit intake,[44] and antioxidant intake are associated with a lower risk of stomach cancer.[4][34] A Mediterranean diet is associated with lower rates of stomach cancer,[45] as is regular aspirin use.[4]

Obesity is a physical risk factor that has been found to increase the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma by contributing to the development of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).[46] The exact mechanism by which obesity causes GERD is not completely known. Studies hypothesize that increased dietary fat leading to increased pressure on the stomach and the lower esophageal sphincter, due to excess adipose tissue, could play a role, yet no statistically significant data have been collected.[47] However, the risk of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma, with GERD present, has been found to increase more than two times for an obese person.[46] There is a correlation between iodine deficiency and gastric cancer.[48][49][50]

Genetics

About 10% of cases run in families, and between 1 and 3% of cases are due to

A genetic risk factor for gastric cancer is a genetic defect of the

The

Heavy metals

Heavy metals, such as arsenic, are commonly found in groundwater and have been linked to gastric cancers. There is a positive and significant relationship between arsenic concentration in groundwater and gastric cancer mortality.[56]

Other

Other risk factors include

In addition,

In a human retrospective study, biliary reflux was found to be a likely risk factor for gastric cancer and precancerous lesions.[62]

Diagnosis

To find the cause of symptoms, the doctor asks about the patient's medical history, does a physical examination, and may order laboratory studies.[63] The patient may also have one or all of these exams:

- fibre optic camera into the stomach to visualise it.[37]

- Upper GI series(may be called barium roentgenogram)

- Computed tomography or CT scanning of the abdomen may reveal gastric cancer. It is more useful to determine invasion into adjacent tissues or the presence of spread to local lymph nodes. Wall thickening of more than 1 cm that is focal, eccentric, and enhancing favours malignancy.[64]

In 2013, Chinese and Israeli scientists reported a successful

Abnormal tissue seen in a gastroscope examination is

Various gastroscopic modalities have been developed to increase yield of detected mucosa with a dye that accentuates the cell structure and can identify areas of dysplasia. Endocytoscopy involves ultra-high magnification to visualise cellular structure to better determine areas of dysplasia. Other gastroscopic modalities such as optical coherence tomography are being tested investigationally for similar applications.[69]

A number of

Various blood tests may be done, including a

Histopathology

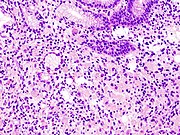

- Gastric signet-ring cells.[citation needed]

- Around 5% of gastric cancers are lymphomas.extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas (MALT type)[75] and to a lesser extent diffuse large B-cell lymphomas.[76] MALT type make up about half of stomach lymphomas.[15]

- Carcinoid and stromal tumors may occur.[citation needed]

-

Poor to moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach. H&E stain.

-

Gastric signet ring cell carcinoma. H&E stain.

-

Adenocarcinoma of the stomach and intestinal metaplasia. H&E stain.

Staging

If cancer cells are found in the tissue sample, the next step is to

Staging may not be complete until after surgery. The surgeon removes nearby lymph nodes and possibly samples of tissue from other areas in the abdomen for examination by a pathologist.[citation needed]

The clinical stages of stomach cancer are:[78][79]

- Stage 0 – Limited to the inner lining of the stomach, it is treatable by endoscopic mucosal resection when found very early (in routine screenings), or otherwise by gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy without need for chemotherapy or radiation.

- Stage I – Penetration to the second or third layers of the stomach (stage 1A) or to the second layer and nearby 5-fluorouracil) and radiation therapy.

- Stage II – Penetration to the second layer and more distant lymph nodes, or the third layer and only nearby lymph nodes, or all four layers but not the lymph nodes, it is treated as for stage I, sometimes with additional neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

- Stage III – Penetration to the third layer and more distant lymph nodes, or penetration to the fourth layer and either nearby tissues or nearby or more distant lymph nodes, it is treated as for stage II; a cure is still possible in some cases.

- Stage IV – Cancer has spread to nearby tissues and more distant lymph nodes, or has metastasized to other organs. A cure is very rarely possible at this stage. Some other techniques to prolong life or improve symptoms are used, including laser treatment, surgery, and/or stents to keep the digestive tract open, and chemotherapy by drugs such as 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, epirubicin, etoposide, docetaxel, oxaliplatin, capecitabine, or irinotecan.[13]

The TNM staging system is also used.[80]

In a study of open-access endoscopy in Scotland, patients were diagnosed 7% in stage I, 17% in stage II, and 28% in stage III.[81] A Minnesota population was diagnosed 10% in stage I, 13% in stage II, and 18% in stage III.[82] However, in a high-risk population in the Valdivia Province of southern Chile, only 5% of patients were diagnosed in the first two stages and 10% in stage III.[83]

Prevention

Getting rid of H. pylori in those who are infected decreases the risk of stomach cancer.

Management

Cancer of the stomach is difficult to cure unless it is found at an early stage (before it has begun to spread). Unfortunately, because early stomach cancer causes few symptoms, the disease is usually advanced when the diagnosis is made.[90]

Treatment for stomach cancer may include surgery,[91] chemotherapy,[13] or radiation therapy.[92] New treatment approaches such as immunotherapy or gene therapy and improved ways of using current methods are being studied in clinical trials.[93]

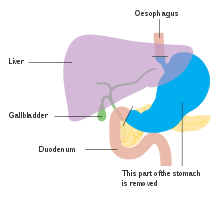

Surgery

Surgery remains the only curative therapy for stomach cancer.

Those with metastatic disease at the time of presentation may receive palliative surgery, and while it remains controversial, due to the possibility of complications from the surgery itself and because it may delay chemotherapy, the data so far are mostly positive, with improved survival rates being seen in those treated with this approach.[6][96]

Chemotherapy

The use of chemotherapy to treat stomach cancer has no firmly established

Targeted therapy

Recently[

Radiation

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) may be used to treat stomach cancer, often as an adjuvant to chemotherapy and/or surgery.[6]

Lymphoma

MALT lymphomas are often completely resolved after the underlying H. pylori infection is treated.[15] This results in remission in about 80% of cases.[15]

Prognosis

The prognosis of stomach cancer is generally poor, because the tumor has often metastasized by the time of discovery, and most people with the condition are elderly (median age is between 70 and 75 years) at presentation.[99] The average life expectancy after being diagnosed is around 24 months, and the five-year survival rate for stomach cancer is less than 10%.[6]

Almost 300 genes are related to outcomes in stomach cancer, with both unfavorable genes where high expression is related to poor survival and favorable genes where high expression is associated with longer survival times.

Epidemiology

In 2018, stomach cancer was the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide, representing 5.7% of all cancer cases, and the third leading cause of death from cancers, being responsible for 8.2% of all cancer deaths.[103] Among men, 683 754 cases were diagnosed, accounting for 7.2% of all cancer cases, and among women, stomach cancer was diagnosed in 349 947 cases, accounting for 4.1% of all cancer cases.[103]

In 2012, stomach cancer was the fifth most-common cancer with 952,000 cases diagnosed.[16] It is more common both in men and in developing countries.[104][105] In 2012, it represented 8.5% of cancer cases in men, making it the fourth most-common cancer in men.[106] Also in 2012, the number of deaths was 700,000, having decreased slightly from 774,000 in 1990, making it the third-leading cause of cancer-related death (after lung cancer and liver cancer).[107][108]

Less than 5% of stomach cancers occur in people under 40 years of age, with 81.1% of that 5% in the age-group of 30 to 39 and 18.9% in the age-group of 20 to 29.[109]

In 2014, stomach cancer resulted in 0.61% of deaths (13,303 cases) in the United States.[110] In China, stomach cancer accounted for 3.56% of all deaths (324,439 cases).[111][unreliable source?] The highest rate of stomach cancer was in Mongolia, at 28 cases per 100,000 people.[112][unreliable source?]

In the United Kingdom, stomach cancer is the 15th most-common cancer (around 7,100 people were diagnosed with stomach cancer in 2011), and it is the 10th most-common cause of cancer-related deaths (around 4,800 people died in 2012).[113]

Incidence and mortality rates of gastric cancer vary greatly in Africa. The GLOBOCAN system is currently the most widely used method to compare these rates between countries, but African incidence and mortality rates are seen to differ among countries, possibly due to the lack of universal access to a registry system for all countries.[114] Variation as drastic as estimated rates from 0.3/100000 in Botswana to 20.3/100000 in Mali have been observed.[114] In Uganda, the incidence of gastric cancer has increased from the 1960s measurement of 0.8/100000 to 5.6/100000.[114] Gastric cancer, though present, is relatively low when compared to countries with high incidence like Japan and China. One suspected cause of the variation within Africa and between other countries is due to different strains of the H. pylori bacteria. The trend commonly seen is that H. pylori infection increases the risk for gastric cancer, but this is not the case in Africa, giving this phenomenon the name the "African enigma".[115] Although this bacterial species is found in Africa, evidence has supported that different strains with mutations in the bacterial genotype may contribute to the difference in cancer development between African countries and others outside the continent.[115] Increasing access to health care and treatment measures have been commonly associated with the rising incidence, though, particularly in Uganda.[114]

Other animals

The stomach is a muscular organ of the

A carcinogenic interaction was demonstrated between bile acids and Helicobacter pylori in a mouse model of gastric cancer.[117][118]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Gastric Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". NCI. 17 April 2014. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "5.4 Stomach Cancer". World Cancer Report 2014. 2014.

- ^ PMID 20930075.

- ^ S2CID 22918077.

- ^ a b c "Stomach (Gastric) Cancer Prevention (PDQ®)". NCI. 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ PMID 24587643.

- ^ a b "Cancer of the Stomach - Cancer Stat Facts". SEER. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ a b "がん診療連携拠点病院等院内がん登録生存率集計: [国立がん研究センター がん登録・統計]". ganjoho.jp. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ ISSN 0007-9235.

- ^ "Stomach (Gastric) Cancer". NCI. January 1980. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-19-517543-1. Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-335-24422-5.

- ^ PMID 28850174.

- PMID 33798523.

- ^ S2CID 6796557.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9.

- S2CID 52188256.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-0637-8.

- ISBN 978-1-60831-782-0.

- ]

- ISBN 978-0-306-47885-7.

- ^ "Statistics and outlook for stomach cancer". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- S2CID 4017466.

- ^ "Guidance on Commissioning Cancer Services Improving Outcomes in Upper Gastro-intestinal Cancers" (PDF). NHS. January 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2012.

- ^ "Symptoms of stomach cancer". nhs.uk. 17 September 2018.

- PMID 33641020.

- PMID 23725070. Archived from the original(PDF) on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- PMID 18755583.

- S2CID 14288660.

- ^ "Proceedings of the fourth Global Vaccine Research Forum" (PDF). Initiative for Vaccine Research team of the Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. WHO. April 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer...

- S2CID 5721063.

- S2CID 257804097.

- ^ "Developing a vaccine for the Epstein–Barr Virus could prevent up to 200,000 cancers globally say experts". Cancer Research UK. 24 March 2014. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ a b "What Are The Risk Factors For Stomach Cancer(Website)". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- PMID 2208177.

- S2CID 42758668.

- ^ S2CID 16351105.

- PMID 11014322.

- PMID 28826375.

- PMID 37447308.

- ^ PMID 31584199.

- PMID 11945131. Archived from the originalon 6 October 2011.

- PMID 16865769.

- ^ PMID 32525569.

- PMID 20007304.

- ^ PMID 16489633.

- S2CID 15540274.

- ISBN 978-0-12-374135-6.

- ISSN 1872-3136.

- PMID 10936894.

- ^ a b c d e "Hereditary Diffuse Cancer". No Stomach for Cancer. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- PMID 32651972.

- ^ "Gastric Cancer — Adenocarcinoma". International Cancer Genome Consortium. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Gastric Cancer—Intestinal- and diffuse-type". International Cancer Genome Consortium. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- PMID 15235021.

- PMID 37726351.

- PMID 24587649.

- PMID 23075625.

- PMID 15227748.

- PMID 16952033.

- S2CID 226218796.

- PMID 32187838.

- ^ "Gastric Cancer". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- PMID 22935192.

- PMID 23462808.

- ^ Paddock C (6 March 2013). "Breath Test Could Detect And Diagnose Stomach Cancer". Medical News Today. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- S2CID 206961387.

- PMID 34887450.

- S2CID 34445155.

- S2CID 37434568.

- ^ Beg M, Singh M, Saraswat MK, Rewari BB (2002). "Occult Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Detection, Interpretation, and Evaluation" (PDF). JIACM. 3 (2): 153–58. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2010.

- PMID 1891020.

- ISBN 978-1-4160-3121-5.

- ^ Kumar 2010, p. 786

- PMID 28151409.

- S2CID 10160642.

- PMID 16418249.

- ^ "Detailed Guide: Stomach Cancer Treatment Choices by Type and Stage of Stomach Cancer". American Cancer Society. 3 November 2009. Archived from the original on 8 October 2009.

- ^ Slowik G (October 2009). "What Are The Stages Of Stomach Cancer?". ehealthmd.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010.

- ^ "Detailed Guide: Stomach Cancer: How Is Stomach Cancer Staged?". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 25 March 2008.

- S2CID 31841360.

- PMID 18828967.

- PMID 19370783.

- PMID 24846275.

- PMID 25339056.

- PMID 25549091.

- PMID 18677777.

- PMID 22419320.

- PMID 35566209.

- PMID 23639645.

- PMID 23983442.

- PMID 23622077.

- ^ PMID 21556317.

- PMID 27030300.

- ^ S2CID 58584460.

- (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2014.

- S2CID 24196381.

- ^ PMID 23348899.

- ^ Gastric Cancer at eMedicine

- ^ "The stomach cancer proteome – The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org.

- PMID 28818916.

- PMID 32070268.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-4-000129-9.

- S2CID 13746942.

- ^ "Are the number of cancer cases increasing or decreasing in the world?". WHO Online Q&A. WHO. 1 April 2008. Archived from the original on 14 May 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ^ World Cancer Report 2014. 2014.

- S2CID 1541253.

- ^ "PRESS RELEASE N° 224 Global battle against cancer won't be won with treatment alone: Effective prevention measures urgently needed to prevent cancer crisis" (PDF). World Health Organization. 3 February 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- from the original on 3 July 2009.

- ^ "Health profile: United States". Le Duc Media. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Health profile: China". Le Duc Media. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Stomach Cancer: Death Rate Per 100,000". Le Duc Media. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ "Stomach cancer statistics". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ^ PMID 24833842.

- ^ S2CID 25990463.

- ISBN 978-0-323-24197-7.

- PMID 35575088.

- PMID 35316215.

External links

- "Gastric cancer treatment guidelines". National Cancer Institute. 14 October 2022.