Suebi

The Suebi (also spelled Suevi) or Suebians were a large group of

Although Tacitus specified that the Suebian group was not an old tribal group itself, the Suebian peoples are associated by Pliny the Elder with the Irminones, a grouping of Germanic peoples who claimed ancestral connections. Tacitus mentions Suebian languages, and a geographical "Suevia".

The Suevians were first mentioned by Julius Caesar in connection with the invasion of Gaul by the Germanic king Ariovistus during the Gallic Wars. Unlike Tacitus he described them as a single people, distinct from the Marcomanni, within the larger Germanic category who he saw as a growing threat to Gaul and Italy in the first century BC, as they had been moving southwards aggressively, at the expense of Gallic tribes, and establishing a Germanic presence in the immediate areas north of the Danube. In particular, he saw the Suebians as the most warlike of the Germanic peoples.

During the reign of Augustus the first emperor, Rome made aggressive campaigns into Germania, east of the Rhine and north of the Danube, pushing towards the Elbe. After suffering a major defeat to the Romans in 9 BC, Maroboduus became king of a Suevian kingdom which was established within the protective mountains and forests of Bohemia. The Suevians did not join the alliance led by Arminius.[2]

In 69 AD the Suebian kings Italicus and Sido provided support to the Flavian faction under Vespasian.[3]

Under the reign of

By the

By the late 4th century AD, the Middle Danubian frontier inhabited by the Quadi and Marcomanni received large numbers of Gothic and other eastern peoples escaping disturbances associated with the

During the last years of the decline of the Western Roman Empire, the Suebian general Ricimer was its de facto ruler.[6] The Lombards, with many Danubian peoples both Suebian and eastern, later settled Italy and established the Kingdom of the Lombards.

The Alamanni,

Etymology

Etymologists trace the name from Proto-Germanic *swēbaz based on the Proto-Germanic root *swē- found in the third-person reflexive pronoun, giving the meaning "one's own" people,[9] in turn from an earlier Indo-European root *swe- (Polish swe, swój, swoi, Latin sui, Italian suo, Sanskrit swa, each meaning "one's own").[10]

The etymological sources list the following ethnic names as being from the same root:

Alternatively, it may be borrowed from a Celtic word for "vagabond".[11]

Classification

More than one tribe

Caesar placed the Suebi east of the Ubii apparently near modern Hesse, in the position where later writers mention the Chatti, and he distinguished them from their allies the Marcomanni. Some commentators believe that Caesar's Suebi were the later Chatti or possibly the Hermunduri, or Semnones.[12] Later authors use the term Suebi more broadly, "to cover a large number of tribes in central Germany".[13]

While Caesar treated them as one Germanic tribe within an alliance, albeit the largest and most warlike one, later authors, such as Tacitus, Pliny the Elder and Strabo, specified that the Suevi "do not, like the Chatti or Tencteri, constitute a single nation. They actually occupy more than half of Germania, and are divided into a number of distinct tribes under distinct names, though all generally are called Suebi".[14] Although no classical authors explicitly call the Chatti Suevic, Pliny the Elder (23 AD – 79 AD), reported in his Natural History that the Irminones were a large grouping of related Germanic gentes or "tribes" including not only the Suebi, but also the Hermunduri, Chatti and Cherusci.[15] Whether or not the Chatti were ever considered Suevi, both Tacitus and Strabo distinguish the two partly because the Chatti were more settled in one territory, whereas Suevi remained less settled.[16]

The definitions of the greater ethnic groupings within

At one time, classical ethnography had applied the name Suevi to so many Germanic tribes that it appeared as if, in the first centuries AD, that native name would replace the foreign name "Germans".[17]

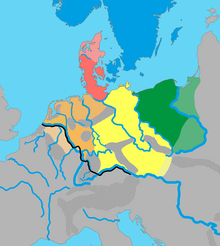

The modern term "Elbe Germanic" similarly covers a large grouping of Germanic peoples that at least overlaps with the classical terms "Suevi" and "Irminones". However, this term was developed mainly as an attempt to define the ancient peoples who must have spoken the Germanic dialects that led to modern Upper German dialects spoken in Austria, Bavaria, Thuringia, Alsace, Baden-Württemberg and German speaking Switzerland. This was proposed by Friedrich Maurer as one of five major Kulturkreise or "culture-groups" whose dialects developed in the southern German area from the first century BC through to the fourth century AD.[18] Apart from his own linguistic work with modern dialects, he also referred to the archaeological and literary analysis of Germanic tribes done earlier by Gustaf Kossinna[19] In terms of these proposed ancient dialects, the Vandals, Goths and Burgundians are generally referred to as members of the Eastern Germanic group, distinct from the Elbe Germanic.

Tribes names in classical sources

Northern bank of the Danube

In the time of Caesar, southern Germany had a mixture of

Strabo (64/63 BC – c. 24 AD), in Book IV (6.9) of his Geography also associates the Suebi with the

Approaching the Rhine

Caesar describes the Suebi as pressing the German tribes of the Rhine, such as the Tencteri, Usipetes and Ubii, from the east, forcing them from their homes. While emphasizing their warlike nature he writes as if they had a settled homeland somewhere between the Cherusci and the Ubii, and separated from the Cherusci by a deep forest called the Silva Bacenis. He also describes the Marcomanni as a tribe distinct from the Suebi, and also active within the same alliance. But he does not describe where they were living.

Strabo wrote that the Suebi "excel all the others in power and numbers."[26] He describes Suebic peoples (Greek ethnē) as having come to dominate Germany between the Rhine and Elbe, with the exception of the Rhine valley, on the frontier with the Roman empire, and the "coastal" regions north of the Rhine.

The geographer

As discussed below, in the third century a large group of Suebi, also referred to as the

The Elbe

Strabo does not say much about the Suebi east of the Elbe, saying that this region was still unknown to Romans,

From Tacitus and Ptolemy we can derive more details:

- The Hercynian forest). A monument confirms that the Juthungi, who fought the Romans in the 3rd century, and were associated with the Alamanni, were Semnones.

- The Langobardi live a bit further from Rome's borders, in "scanty numbers" but "surrounded by a host of most powerful tribes" and kept safe "by daring the perils of war" according to Tacitus.[32]

- Tacitus names seven tribes who live "next" after the Langobardi, "fenced in by rivers or forests" stretching "into the remoter regions of Germany". These all worshiped Nuitones.[32]

- At the mouth of the Elbe (and in the Danish peninsula), the classical authors do not place any Suevi, but rather the Chauci to the west of the Elbe, and the Saxons to the east, and in the "neck" of the peninsula.

Note that while various errors and confusions are possible, Ptolemy places the Angles and Langobardi west of the Elbe, where they may indeed have been present at some points in time, given that the Suebi were often mobile.

East of the Elbe

It is already mentioned above that stretching between the Elbe and the Oder, the classical authors place the Suebic Semnones. Ptolemy places the

According to Tacitus, around the north of the Danubian Marcomanni and Quadi, "dwelling in forests and on mountain-tops", live the

Beyond this mountain range (probably the modern

These Burgundians who according to Ptolemy lived between the Baltic sea Germans and the Lugii, stretching between the Suevus and Vistula rivers, were described by Pliny the Elder (as opposed to Tacitus) as being not Suevic but

Baltic Sea

Tacitus called the Baltic sea the Suebian sea. Pomponius Mela wrote in his Description of the World (III.3.31) beyond the Danish isles are "the farthest people of Germania, the Hermiones".

North of the Lugii, near the Baltic Sea, Tacitus places the Gothones (Goths), Rugii, and Lemovii. These three Germanic tribes share a tradition of having kings, and also similar arms – round shields and short swords.[33] Ptolemy says that east of the Saxons, from the "Chalusus" river to the "Suevian" river are the Farodini, then the Sidini up to the "Viadua" river, and after these the "Rugiclei" up to the Vistula river (probably referring to the "Rugii" of Tacitus). He does not specify if these are Suevi.

In the sea, the states of the

Tacitus describes the non-Germanic

Cultural characteristics

Caesar noted that rather than grain crops, they spent time on animal husbandry and hunting. They wore animal skins, bathed in rivers, consumed milk and meat products, and prohibited wine, allowing trade only to dispose of their booty and otherwise they had no goods to export. They had no private ownership of land and were not permitted to stay resident in one place for more than one year. They were divided into 100 cantons, each of which had to provide and support 1000 armed men for the constant pursuit of war.

Strabo describes the Suebi and people from their part of the world as highly mobile and nomadic, unlike more settled and agricultural tribes such as the Chatti and Cherusci:

...they do not till the soil or even store up food, but live in small huts that are merely temporary structures; and they live for the most part off their flocks, as the Nomads do, so that, in imitation of the Nomads, they load their household belongings on their wagons and with their beasts turn whithersoever they think best.

Notable in classical sources, the Suebi can be identified by their hair style called the "Suebian knot", which "distinguishes the freeman from the slave";[38] or in other words served as a badge of social rank. The same passage points out that chiefs "use an even more elaborate style".

Tacitus mentions the sacrifice of humans practiced by the

Language

While there is debate possible about whether all tribes identified by Romans as Germanic spoke a Germanic language, the Suebi are generally agreed to have spoken one or more Germanic languages. Tacitus refers to Suebian languages, implying there was more than one by the end of the first century. In particular, the Suebi are associated with the concept of an "Elbe Germanic" group of early dialects spoken by the Irminones, entering Germany from the east, and originating on the Baltic. In late classical times, these dialects, by now situated to the south of the Elbe, and stretching across the Danube into the Roman empire, experienced the High German consonant shift that defines modern High German languages, and in its most extreme form, Upper German.[39]

Modern Swabian German, and Alemannic German more broadly, are therefore "assumed to have evolved at least in part" from Suebian.[40] However, Bavarian, the Thuringian dialect, the Lombardic language spoken by the Lombards of Italy, and standard "High German" itself, are also at least partly derived from the dialects spoken by the Suebi. (The only non-Suebian name among the major groups of Upper Germanic dialects is High Franconian German, but this is on the transitional frontier with Central German, as is neighboring Thuringian.)[39]

Historical events

Ariovistus and the Suebi in 58 BC

Julius Caesar (100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) describes the Suebi in his firsthand account,

Caesar confronted a large army led by a Suevic King named Ariovistus in 58 BC who had been settled for some time in Gaul already, at the invitation of the Gaulish Arverni and Sequani as part of their war against the Aedui. He had already been recognized as a king by the Roman senate. Ariovistus forbade the Romans from entering into Gaul. Caesar on the other hand saw himself and Rome as an ally and defender of the Aedui.

The forces Caesar faced in battle were composed of "

, and Suevi". While Caesar was preparing for conflict, a new force of Suebi was led to the Rhine by two brothers, Nasuas and Cimberius, forcing Caesar to rush in order to try to avoid the joining of forces.Caesar defeated Ariovistus in battle, forcing him to escape across the Rhine. When news of this spread, the fresh Suebian forces turned back in some panic, which led local tribes on the Rhine to take advantage of the situation and attack them.

Caesar and the Suebi in 55 BC

Also reported within Caesar's accounts of the Gallic wars, the Suebi posed another threat in 55 BC.[42] The Germanic Ubii, who had worked out an alliance with Caesar, were complaining of being harassed by the Suebi, and the Tencteri and Usipetes, already forced from their homes, tried to cross the Rhine and enter Gaul by force. Caesar bridged the Rhine, the first known to do so, with a pile bridge, which though considered a marvel, was dismantled after only eighteen days. The Suebi abandoned their towns closest to the Romans, retreated to the forest and assembled an army. Caesar moved back across the bridge and broke it down, stating that he had achieved his objective of warning the Suebi. They in turn supposedly stopped harassing the Ubii. The Ubii were later resettled on the west bank of the Rhine, in Roman territory.

Rhine crossing of 29 BC

The victory of Drusus in 9 BC

Florus (c. 74 AD – c. 130 AD), gives a more detailed view of the operations of 9 BC. He reports that the Cherusci, Suebi and Sicambri formed an alliance by crucifying twenty Roman centurions, but that Drusus defeated them, confiscated their plunder and sold them into slavery.[46] Presumably only the war party was sold, as the Suebi continue to appear in the ancient sources.

Florus's report of the peace brought to Germany by Drusus is glowing but premature. He built "more than five hundred forts" and two bridges guarded by fleets. "He opened a way through the Hercynian Forest", which implies but still does not overtly state that he had subdued the Suebi. "In a word, there was such peace in Germany that the inhabitants seemed changed ... and the very climate milder and softer than it used to be."

In the

Augustus planned in 6 AD to destroy the kingdom of Maroboduus, which he considered to be too dangerous for the Romans. The later emperor

Roman defeat in 9 AD

After the death of Drusus, the

Aftermath of 9 AD

Subsequently, Augustus placed Germanicus, the son of Drusus, in charge of the forces of the Rhine and he, after dealing with a mutiny among his troops, proceeded against the Cherusci and their allies, breaking their power finally at the battle of Idistavisus, a plain on the Weser. All eight legions and supporting units of Gauls were required in order to accomplish this.[49] Germanicus' zeal led finally to his being replaced (17 AD) by his cousin Drusus, Tiberius' son, as Tiberius thought it best to follow his predecessor's policy of limiting the empire. Germanicus certainly would have involved the Suebi, with unpredictable results.[47]

The resulting battle was indecisive but Maroboduus withdrew to Bohemia and sent for assistance to Tiberius. He was refused on the grounds that he had not moved to help Varus. Drusus encouraged the Germans to finish him off. A force of Goths under Catualda, a Marcomannian exile, bought off the nobles and seized the palace. Maroboduus escaped to Noricum and the Romans offered him refuge in Ravenna where he remained the rest of his life.[51] He died in 37 AD. After his expulsion the leadership of the Marcomanni was contested by their Suebic neighbours and allies, the Hermunduri and Quadi.

Marcomannic wars

In the 2nd century AD, the Marcomanni entered into a confederation with other peoples including the

In the third century Jordanes claims that the Marcomanni paid tribute to the Goths, and that the princes of the Quadi were enslaved. The Vandals, who had moved south towards Pannonia, were apparently still sometimes able to defend themselves.[52]

Migration period

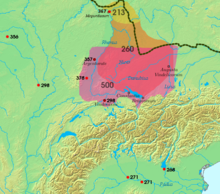

In 259/60, one or more groups of Suebi appear to have been the main element in the formation of a new tribal alliance known as the

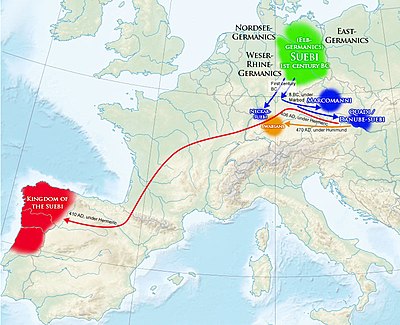

These Suebi for the most part stayed on the east bank of the Rhine until 31 December 406, when much of the tribe joined the Vandals and Alans in breaching the Roman frontier by crossing the Rhine, perhaps at Mainz, thus launching an invasion of northern Gaul. It is thought that this group probably contained a significant amount of Quadi, moving out of their homeland under pressure from Radagaisus.

Other Suebi apparently remained in or near to the original homeland areas near the Elbe and the modern Czech Republic, occasionally still being referred to by this term. They expanded eventually into Roman areas such as Switzerland, Austria, and Bavaria, possibly pushed by groups arriving from the east.

Further south, a group of Suebi settled in parts of Pannonia, after the Huns were defeated in 454 in the Battle of Nedao. Later, the Suebian king Hunimund fought against the Ostrogoths in the battle of Bolia in 469. The Suebian coalition lost the battle, and parts of the Suebi therefore migrated to southern Germany.[53] Probably the Marcomanni made up one significant part of these Suebi, who probably lived in at least two distinct areas.[54] Later, the Lombards, a Suebic group long known on the Elbe, came to dominate the Pannonian region before successfully invading Italy.

Another group of Suebi, the so-called "northern Suebi" were mentioned in 569 under the Frankish king Sigebert I in areas of today's Saxony-Anhalt which were known as Schwabengau or Svebengau at least until the 12th century. In addition to the Svebi, Saxons and Lombards, returning from the Italian Peninsula in 573, are mentioned.

Suevian Kingdom of Gallaecia

Migration

Suebi under king Hermeric, probably coming from the Alemanni, the Quadi, or both,[55] worked their way into the south of France, eventually crossing the Pyrenees and entering the Iberian Peninsula which was no longer under Imperial rule since the rebellion of Gerontius and Maximus in 409.

Passing through the

The Suebic kingdom in Gallaecia and northern Lusitania was established in 410 and lasted until 584. Smaller than the Ostrogothic kingdom of Italy or the Visigothic kingdom in Hispania, it reached a relative stability and prosperity—and even expanded military southwards—despite the occasional quarrels with the neighbouring Visigothic kingdom.

Settlement

The Germanic invaders and immigrants settled mainly in rural areas, as

As the Suebi quickly adopted the local language, few traces were left of their Germanic tongue, but for some words and for their personal and land names, adopted by most of the Gallaeci.[59] In Galicia four parishes and six villages are named Suevos or Suegos, i.e. Sueves, after old Suebic settlements.

Establishment

The

Last years of the kingdom

In 561 king Ariamir called the catholic First Council of Braga, which dealt with the old problem of the Priscillianism heresy. Eight years after, in 569, king Theodemir called the First Council of Lugo,[61] in order to increase the number of dioceses within his kingdom. Its acts have been preserved through a medieval resume known as Parrochiale Suevorum or Divisio Theodemiri.

Defeat by the Visigoths

In 570 the Arian king of the Visigoths,

Religion

Conversion to Arianism

The Suebi remained mostly pagan, and their subjects Priscillianist until an Arian missionary named Ajax, sent by the Visigothic king Theodoric II at the request of the Suebic unifier Remismund, in 466 converted them and established a lasting Arian church which dominated the people until the conversion to Trinitarian Catholicism the 560s.

Conversion to Orthodox Trinitarianism

Mutually incompatible accounts of the conversion of the Suebi to Orthodox Catholic Trinitarian Christianity of the First and Second Ecumenical Councils are presented in the primary records:

- The minutes of the Tui.

- The Martin of Dumio.[64]

- According to the Chararic, having heard of Martin of Tours, promised to accept the beliefs of the saint if only his son would be cured of leprosy. Through the relics and intercession of Saint Martin the son was healed; Chararic and the entire royal household converted to the Nicene faith.[65]

- By 589, when the John of Biclarum, who puts their conversion alongside that of the Goths, occurring under Reccared I in 587–589.

Most scholars have attempted to meld these stories. It has been alleged that Chararic and Theodemir must have been successors of Ariamir, since Ariamir was the first Suebic monarch to lift the ban on Catholic synods; Isidore therefore gets the chronology wrong.

-

Suebic and Roman fibullae fromConimbriga, Portugal

Norse mythology

The name of the Suebi also appears in

See also

- Swabia

- Dukes of Swabia family tree

- Germanic personal names in Galicia

- Laeti

References

Citations

- ISBN 9780191735257. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

Suebi, an elusive term, applied by Tacitus (1) in his Germania to an extensive group of German peoples living east of the Elbe and including the Hermunduri, Marcomanni, Quadi, Semnones, and others, but used rather more narrowly by other Roman writers, beginning with Caesar.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-140-44964-8.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Harm, Volker (2013), ""Elbgermanisch", "Weser-Rhein-Germanisch" und die Grundlagen des Althochdeutschen", in Nielsen; Stiles (eds.), Unity and Diversity in West Germanic and the Emergence of English, German, Frisian and Dutch, North-Western European Language Evolution, vol. 66, pp. 79–99

- ^ Suiones

- ^ Pokorny, Julius. "Root/Lemma se-". Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch. Indo-European Etymological Dictionary (IEED), Department of Comparative Indo-European Linguistics, Leiden University. pp. 882–884. Archived from the original on 2011-08-09. (German language text); locate by searching the page number.Köbler, Gerhard (2000). "*se-" (PDF). Indogermanisches Wörterbuch: 3. Auflage. p. 188. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-25. (German language text); the etymology in English is in Watkins, Calvert (2000). "s(w)e-". Appendix I: Indo-European Roots. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. Some related English words are sibling, sister, swain, self.

- ^

ISBN 978-1-891271-10-6.

- ^ Peck (1898). "Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities".

- ISBN 1-4254-9551-6.

- ^ Tacitus Germania Section 8, translation by H. Mattingly.

- ^ "Book IV section XIV". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ "Strab. 7.1". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ISBN 9780674511736.

- ^ Maurer, Friedrich (1952) [1942]. Nordgermanen und Alemannen: Studien zur germanischen und frühdeutschen Sprachgeschichte, Stammes – und Volkskunde. Bern, München: A. Franke Verlag, Leo Lehnen Verlag.

- ^ Kossinna, Gustaf (1911). Die Herkunft der Germanen. Leipzig: Kabitsch.

- ^ a b "Tac. Ger. 28". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ Dio, Cassius (19 September 2014). Delphi Complete Works of Cassius Dio (Illustrated). Delphi Classics.

- ^ "Strab. 7.1". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ "Section 41". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ "Section 42". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ "Chapt 22". Romansonline.com. Archived from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ Strabo. Geographica. Book IV Chapter 3 Section 4.

- ^ Strabo. "Geography". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ Schütte, Ptolemy's Maps of Northern Europe

- ^ "Geography 7.2". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ "Geography 7.3". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ a b Germania Section 39.

- ^ a b c Germania Section 40.

- ^ a b c "Section 43". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ Section 44.

- ^ a b Germania Section 45

- ^ Section 46.

- S2CID 246879432. A review in English of Neumann, Gunter; Henning Seemann. Beitrage zum Verstandnis der Germania des Tacitus, Teil II: Bericht uber die Kolloquien der Kommission fur die Altertumskunde Nord- und Mitteleuropas im Jahre 1986 und 1987. A German-language text.

- ^ Section 38.

- ^ a b Robinson, Orrin (1992), Old English and its Closest Relatives pages 194–5.

- ^ Waldman & Mason, 2006, Encyclopedia of European Peoples, p. 784.

- ^ Book IV, sections 1–3, and 19; Book VI, section 10.

- ^ Book IV sections 4–19.

- ^ Dio, Lucius Claudius Cassius. "Dio's Rome". Project Gutenberg. Translated by Herbert Baldwin Foster. pp. Book 51 sections 21, 22.

- ^ Suetonius Tranquillus, Gaius. "The Life of Augustus". The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Bill Thayer in LacusCurtius. pp. section 21.

- ^ Suetonius Tranquillus, Gaius. "The Life of Tiberius". The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Bill Thayer in LacusCurtius. pp. section 9.

- ^ Florus, Lucius Annaeus. Epitome of Roman History. Book II section 30.

- ^ a b Book II section 26.

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, Compendium of Roman History 2, 109, 5; Cassius Dio, Roman History 55, 28, 6–7

- ^ Book II section 16.

- ^ Book II sections 44–46.

- ^ Book II sections 62–63.

- ^ "chapt 16". Romansonline.com. Archived from the original on 2014-05-02. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ Geschichte der Goten. Entwurf einer historischen Ethnographie, C.H. Beck, 1. Aufl. (München 1979), 2. Aufl. (1980), unter dem Titel: Die Goten. Von den Anfängen bis zur Mitte des sechsten Jahrhunderts. 4. Aufl. (2001)

- ^ See Friedrich Lotter on the "Donausueben".

- ^ López Quiroga, Jorge (2001). "Elementos foráneos en las necrópolis tardorromanas de Beiral (Ponte de Lima, Portugal) y Vigo (Pontevedra, España): de nuevo la cuestión del siglo V d. C. en la Península Ibérica" (PDF). CuPAUAM. 27: 115–124. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ "the barbarians, detesting their swords, turn them into ploughs", Historiarum Adversum Paganos, VII, 41, 6.

- ^ "anyone wanting to leave or to depart, uses these barbarians as mercenaries, servers or defenders", Historiarum Adversum Paganos, VII, 41, 4.

- ^ Domingos Maria da Silva, Os Búrios, Terras de Bouro, Câmara Municipal de Terras de Bouro, 2006. (in Portuguese)

- ^ Medieval Galician records show more than 1500 different Germanic names in use for over 70% of the local population. Also, in Galicia, Northern and Central Portugal, there are more than 5.000 toponyms (villages and towns) based on personal Germanic names (Mondariz < *villa *Mundarici; Baltar < *villa *Baldarii; Gomesende < *villa *Gumesenþi; Gondomar < *villa *Gunþumari...); and several toponyms not based on personal names, mainly in Galicia (Malburgo, Samos < Samanos "Congregated", near a hundred Saa/Sá < *Sala "house, palace"...); and some lexical influence on the Galician language and Portuguese language, such as:

laverca "lark" < protogermanic *laiwarikō "lark"

brasa "torch; ember" < protogermanic *blasōn "torch"

britar "to break" < protogermanic *breutan "to break"

lobio "vine gallery" < protogermanic *laubjōn "leaves"

ouva "elf" < protogermanic *albaz "elf"

trigar "to urge" < protogermanic *þreunhan "to urge"

maga "guts (of fish)" < protogermanic *magōn "stomach" - ^ Isidorus Hispalensis, Historia de regibus Gothorum, Vandalorum et Suevorum, 85

- ^ Ferreiro, 199 n11.

- ^ a b c d Thompson, 86.

- ^ St. Martin on Braga wrote in his Formula Vitae Honestae Gloriosissimo ac tranquillissimo et insigni catholicae fidei praedito pietate Mironi regi

- ^ Ferreiro, 198 n8.

- ^ a b Thompson, 83.

- ^ Thompson, 87.

- ^ Ferreiro, 199.

- ^ Thompson, 88.

- ^ Ferreiro, 207.

- ^ Peterson, Lena. (2002). Nordiskt runnamnslexikon, at Institutet för språk och folkminnen, Sweden. Archived October 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

General sources

- Ferreiro, Alberto. "Braga and Tours: Some Observations on Gregory's De virtutibus sancti Martini." Journal of Early Christian Studies. 3 (1995), p. 195–210.

- ISBN 0-19-822543-1.

- Reynolds, Robert L., "Reconsideration of the history of the Suevi", Revue belge de pholologie et d'histoire, 35 (1957), p. 19–45.

External links

- The Chronicle of Hydatius is the main source for the history of the Suebi in Galicia and Portugal up to 468.

- Identity and Interaction: the Suevi and the Hispano-Romans, University of Virginia, 2007

- Medieval Galician anthroponomy

- Minutes of the Councils of Braga and Toledo, in the Collectio Hispana Gallica Augustodunensis

- Orosius' Historiarum Adversum Paganos Libri VII