Suicide methods

| Suicide |

|---|

A suicide method is any means by which a person may choose to

Worldwide, three suicide methods predominate with the pattern varying in different countries. These are hanging, poisoning by pesticides, and firearms.[2]

Some suicides may be preventable by removing the means.

Purpose of study

The

Such information allows public health resources to focus on the problems that are relevant in a particular place, or for a given population or subpopulation.[13] For instance, if firearms are used in a significant number of suicides in one place, then public health policies there could focus on gun safety, such as keeping guns locked away, and the key inaccessible to at-risk family members. If young people are found to be at increased risk of suicide by overdosing on particular medications, then an alternative class of medication may be prescribed instead, a safety plan and monitoring of medication can be put in place, and parents can be educated about how to prevent the hoarding of medication for a future suicide attempt.[11]

Media reporting

Media reporting of the methods used in suicides is "strongly discouraged" by the

Media reporting guidelines also apply to "online content including citizen-generated media coverage". The Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide, created by journalists, suicide prevention groups, and

Method restriction

Method restriction, also called lethal means reduction, is an effective way to reduce the number of suicide deaths in the short and medium term.

Method restriction is effective and prevents suicides.[16] It has the largest effect on overall suicide rates when the method being restricted is common and no direct substitution is available.[16] If the method being restricted is uncommon, or if a substitute is readily available, then it may be effective in individual cases but not produce a large-scale reduction in the number of deaths in a country.[16]

Method substitution is the process of choosing a different suicide method when the first-choice method is inaccessible.[3] In many cases, when the first-choice method is restricted, the person does not attempt to find a substitute.[16] Method substitution has been measured over the course of decades, so when a common method is restricted (for example, by making domestic gas less toxic), overall suicide rates may be suppressed for many years.[3][16] If the first-choice suicide method is inaccessible, a method substitution may be made which may be less lethal, tending to result in fewer fatal suicide attempts.[3]

In an example of the curb cut effect, changes unrelated to suicide have also functioned as suicide method restrictions.[16] Examples of this include changes to align train doors with platforms, switching from coal gas to natural gas in homes, and gun control laws, all of which have reduced suicides despite being intended for a different purpose.[16]

List

Suffocation

Suicide by suffocation involves restricting breathing or the amount of oxygen taken in, causing

Hanging

Hanging is the prevalent means of suicide in impoverished

Hanging was the most common method in

Drowning

Suicide by

Poisoning

Suicide by

Pesticide

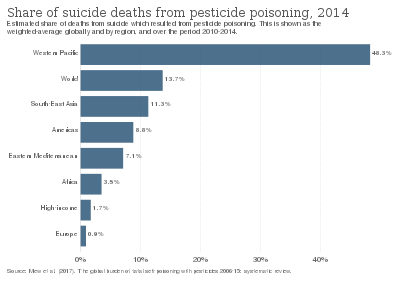

As of 2006[update], worldwide, around 30% of suicides were from pesticide poisonings.[40] The use of this method varies markedly in different areas of the world, from 0.9% in Europe to about 50% in the Pacific region.[39] In the US, pesticide poisoning is very rare, being used in about 12 suicides per year.[41] The overall case fatality rate for suicide attempts using pesticide is about 10–20%.[42]

Method restriction has been an effective way to reduce suicide by poisoning in many countries. In Finland, limiting access to parathion in the 1960s resulted in a rapid decline in both poisoning-related suicides and total suicide deaths for several years, and a slower decline in subsequent years.[43] In Sri Lanka, both suicide by pesticide and total suicides declined after first toxicity class I and later class II endosulfan were banned.[44] Overall suicide deaths were cut by 70%, with 93,000 lives saved over 20 years as a result of banning these pesticides.[2] In Korea, banning a single pesticide, paraquat, halved the number of suicides by pesticide poisoning[2] and reduced the total number of suicides in that country.[43]

Drug overdose

A drug overdose involves taking a dose of a drug that exceeds safe levels. In the UK (England and Wales) until 2013, a drug overdose was the most common suicide method in females.[45] In 2019 in males the percentage is 16%. Self-poisoning accounts for the highest number of non-fatal suicide attempts. In the United States about 60% of suicide attempts and 14% of suicide deaths involve drug overdoses.[28] The risk of death in suicide attempts involving overdose is about 2%.[28][verification needed]

Overdose attempts using

Carbon monoxide

A particular type of poisoning involves the inhalation of high levels of

Carbon monoxide is a colorless and odorless gas, so its presence cannot be detected by sight or smell. It acts by binding preferentially to the hemoglobin in the bloodstream, displacing oxygen molecules and progressively deoxygenating the blood, eventually resulting in the failure of cellular respiration and death. Carbon monoxide is extremely dangerous to bystanders and people who may discover the body; right-to-die advocate Philip Nitschke has therefore recommended against this method.[55][self-published source?]

Before air quality regulations and catalytic converters, suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning was often achieved by running a car's engine in an enclosed space such as a garage, or by redirecting a running car's exhaust back inside the cabin with a hose. Motor car exhaust may have contained up to 25% carbon monoxide. Catalytic converters found on all modern automobiles eliminate over 99% of carbon monoxide produced.[56] As a further complication, the amount of unburned gasoline in emissions can make exhaust unbearable to breathe well before a person loses consciousness.

Other toxins

Gas-oven suicide was a common method of suicide in the early to mid-20th centuries in some North American and European countries. Household gas was originally

Shooting

In the United States, suicide by firearm is the most lethal method of suicide, resulting in a fatality 90% of the time,[28] and is thus the leading cause of death by suicide as of 2017.[64] Worldwide, firearm prevalence in suicides varies widely, depending on the acceptance and availability of firearms in a culture. The use of firearms in suicides ranges from less than 10% in Australia[65] to 50.5% in the U.S., where it is the most common method of suicide.[66]

Generally, the bullet will be aimed at point-blank range. Surviving a self-inflicted gunshot may result in severe chronic pain as well as reduced cognitive abilities and motor function, subdural hematoma, foreign bodies in the head, pneumocephalus and cerebrospinal fluid leaks. For temporal bone directed bullets, temporal lobe abscess, meningitis, aphasia, hemianopsia, and hemiplegia are common late intracranial complications. As many as 50% of people who survive gunshot wounds directed at the temporal bone suffer facial nerve damage, usually due to a severed nerve.[67]

Gun control

Reducing access to guns at a population level decreases the risk of suicide by firearms.[68][69][70]

Fewer people die from suicide overall in places with stricter laws regulating the use, purchase, and trading of firearms.[71][72] Suicide risk goes up when firearms are more available.[73][74][75]

Gun control is a primary method of reducing suicide by people who live in a home with guns. Prevention measures include simple actions such as locking all firearms in a

More firearms are involved in suicide than are involved in homicides in the United States. A 1999 study of California and gun mortality found that a person is more likely to die by suicide if they have purchased a firearm, with a measurable increase of suicide by firearm beginning at most a week after the purchase and continuing for six years or more.[76]

The United States has both the highest number of suicides and firearms in circulation in a developed country, and when gun ownership rises so too does suicide involving the use of a firearm.

A 2006 study found an accelerated decline in firearm-related suicides in Australia after the introduction of nationwide gun control. The same study found no evidence of substitution to other methods.[96] Multiple studies in Canada found that gun suicides declined after gun control, but other methods rose, leading to no change in the overall rates.[97][98][99] Similarly, in New Zealand, gun suicides declined after more legislation, but overall suicide rates did not change;[100] this might be due to the highly stringent firearm storage laws and very low prevalence of handgun ownership in New Zealand.[101] A study about Canada found no significant correlations between provincial firearm ownership and overall provincial suicide rates.[102]

Jumping

Jumping is the most common method of suicide in

Many jumping deaths could be prevented through the construction of fencing or other safety equipment. For example, suicide by jumping into a volcanic crater is a rare method of suicide. Mount Mihara in Japan briefly became a notorious suicide site during the Great Depression following media reports of a suicide there. Copycat suicides in the ensuing years prompted the erection of a protective fence surrounding the crater.[106][107] Similarly, in New Zealand, secure fencing at the Grafton Bridge substantially reduced the rate of suicides.[108] Chest-high barriers are more effective than waist-high barriers because they require more time and effort to climb over.[105]

Constructing barriers is not the only option, and it can be expensive.[109] Other method-specific prevention actions include making staff members visible in high-risk areas, using closed-circuit television cameras to identify people in inappropriate places or behaving abnormally (e.g., lingering in a place that people normally spend little time in), and installing awnings and soft-looking landscaping, which deters suicide attempts by making the place look ineffective.[109]

Another factor in reducing jumping deaths is to avoid suggesting in news articles, signs, or other communication that a high-risk place is a common, appropriate, or effective place for dying by jumping from.[109] The efficacy of signage is uncertain, and may depend on whether the wording is simple and appropriate.[109]

Cutting and stabbing

A fatal self-inflicted wound to the wrist is termed a deep wrist injury, and is often preceded by several tentative surface-breaking attempts known as hesitation wounds, indicating indecision or a self-harm tactic.[110] For every suicide by wrist cutting, there are many more nonfatal attempts, so that the number of actual deaths using this method is very low.[111]

Wounds from suicide attempts involve the non-dominant hand, with damage often done to the median nerve, ulnar nerve, radial artery, palmaris longus muscle, and flexor carpi radialis muscle.[112][110] Such injuries can severely affect the function of the hand, and the inability caused to carry out work or interests increases the risk of further attempts.[110]

Seppuku is a form of Japanese ritual suicide by disembowelment. It was originally reserved for samurai in their code of honour. It is not often used in the modern day because it is painful and slow.[113][114]

Starvation and dehydration

A classification has been made of Voluntarily Stopping Eating and Drinking (VSED) which is often resorted to by those with a terminal illness.[115][116] This includes fasting and dehydration, and has also been referred to as autoeuthanasia.[117] It has been used by assisted dying activists, such as Wendy Mitchell, as an means of death in places where assisted suicide is not available.

Fasting to death has been used by

Death from dehydration can take from several days to a few weeks. This means that unlike many other suicide methods, it cannot be accomplished impulsively. Those who die by terminal dehydration typically lapse into unconsciousness before death, and may also experience

Terminal dehydration has been described as having substantial advantages over physician-assisted suicide with respect to self-determination, access, professional integrity, and social implications. Specifically, a patient has a right to refuse treatment and it would be a personal assault for someone to force water on a patient, but such is not the case if a doctor merely refuses to provide lethal medication.[123] But it also has distinctive drawbacks as a humane means of voluntary death.[124] One survey of hospice nurses found that nearly twice as many had cared for patients who chose voluntary refusal of food and fluids to hasten death as had cared for patients who chose physician-assisted suicide.[125] They also rated fasting and dehydration as causing less suffering and pain and being more peaceful than physician-assisted suicide.[126][116] Other sources note very painful side effects of dehydration, including seizures, skin cracking and bleeding, blindness, nausea, vomiting, cramping and severe headaches.[127]

Collision with or of a vehicle

Another suicide method is to lie down, or throw oneself, in the path of a fast-moving vehicle, either on the road or onto railway tracks. Nonfatal attempts may result in profound injuries, such as

Road

Some people use intentional car crashes as a suicide method. This especially applies to single-occupant, single-vehicle wrecks,

The real percentage of suicides among motor vehicle fatalities is not reliably known and likely varies by the ease of accessing a car and the ease of accessing other methods. One review article suggested that more than 2% of crashes result from suicidal intent.[131] A study in Switzerland indicated that 1% of deaths by suicide involved a motor vehicle collision.[132]

Rail

Air

Toward the end of the 20th century, one or two pilots in the US

Disease

There have been documented cases of gay men deliberately trying to contract a disease such as HIV/AIDS as a means of suicide.[142][143][144]

Electrocution

Suicide by electrocution involves using a lethal

Fire

Hypothermia

Hypothermia is a rare method of suicide. Between 1991 and 2014 in the United States, there were eight cases in the scientific literature, and they usually involved some other factor like drugs.[150]

Assisted suicide

Indirect

Indirect suicide is the act of setting out on an obviously fatal course without directly carrying out the act upon oneself. Indirect suicide is differentiated from legally defined suicide by the fact that the person does not directly cause the action meant to kill them, but rather expects and allows the action to happen to them. Examples of indirect suicide include a soldier enlisting in the army with the intention and expectation of being killed in combat, or provoking an armed law enforcement officer into using lethal force against them. The latter is generally called "suicide by cop".

Evidence exists for suicide by

Rituals

See also

- Advocacy of suicide

- List of suicides from antiquity to the present

- List of suicides in the 21st century

- Sarco device

- Suicide bag

- Suicide legislation

References

- ^ "Preventing Suicide |Violence Prevention|Injury Centerf". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 September 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Suicide: one person dies every 40 seconds". World Health Organization. 9 September 2019.

- ^ PMID 26385066.

- ^ PMID 22726520.

- ^ "Worrying trends in U.S. suicide rates".

- ^ "Suicide". www.who.int. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- PMID 26905895.

- ^ "Suicide Risk and Protective Factors|Suicide|Violence Prevention|Injury Center". www.cdc.gov. 25 April 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- PMID 22977392.

- ^ National Institute of Mental Health: Suicide in the U.S.: Statistics and Prevention [1]

- ^ ISBN 978-1-61537-163-1.

- ^ a b "First WHO report on suicide prevention calls for coordinated action to reduce suicides worldwide". WHO. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Campaign materials – handouts". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- PMID 31071144.

- ^ "Reporting on Suicide: Recommendations for the Media". American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Archived from the original on 31 October 2004. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-102683-6.

- ^ Solomon A (9 June 2018). "Anthony Bourdain, Kate Spade, and the Preventable Tragedies of Suicide". New Yorker. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "Online Media". Reporting on Suicide. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- PMID 22726520.

- ^ PMID 29436398.

- ^ from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ PMID 27197046.

- ^ a b "Suicides in the UK". www.ons.gov.uk – Office for National Statistics.

- ^ Kurzban R (7 February 2011). "Why Can't You Hold Your Breath Until You're Dead?". Web. Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Deaths Involving the Inadvertent Connection of Air-line Respirators to Inert Gas Supplies".

- PMID 19022078.

- ^ Howard M, Hall M, Jeffrey D et al., "Suicide by Asphyxiation due to Helium Inhalation, Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2010; accessed 12 May 2014

- ^ S2CID 208611916.

- PMID 24949083.

- ISBN 978-1-57230-541-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-30170-1.

- ISBN 978-0-313-35067-2.

- ISBN 978-1-57230-570-0.

- PMID 4719540.

- ^ a b "WISQARS Leading Causes of Death Reports". Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- PMID 35886717.

Drowning is a common suicide method for those with schizophrenia, psychotic disorders and dementia.

- ^ "Poisoning methods". Ctrl-c.liu.se. Archived from the original on 10 May 1996. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ "Poison - Animal, Zootoxins, Biochemistry". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Share of suicide deaths from pesticide poisoning". Our World in Data. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- PMID 16946353.

- ^ "Underlying Cause of Death, 1999–2018 Request". wonder.cdc.gov. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- PMID 14681240.

- ^ PMID 29096617.

- PMID 23950528.

- ^ "Suicides in England and Wales – Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk.

- ISSN 1465-1645. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- ^ PMID 29473717.

- PMID 25732401.

- PMID 18635433.

- S2CID 45739342.

- PMID 21856743.

- ^ Mehta S (25 August 2012). "Metabolism of Paracetamol (Acetaminophen), Acetanilide and Phenacetin". PharmaXChange.info. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- PMID 23393081.

- PMID 12169344.

- ISBN 978-0-9788788-2-5.

- S2CID 34394596.

- ^ "Taking the easy way out?". South China Morning Post. 9 January 2005. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- PMID 12609951.

- ^ "Why have people stopped committing suicide with gas?". gizmodo.com. 9 November 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- S2CID 28751662.

- PMID 11111261.

Table 1

- PMID 26551975.

- ^ "Suicide rate by firearm". Our World in Data. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ "NIMH » Suicide". www.nimh.nih.gov. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "A review of suicide statistics in Australia". Government of Australia. 21 March 2024.

- ^ McIntosh JL, Drapeau CW (28 November 2012). "U.S.A. Suicide: 2010 Official Final Data" (PDF). suicidology.org. American Association of Suicidology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Backous D (5 August 1993). "Temporal Bone Gunshot Wounds: Evaluation and Management". Baylor College of Medicine. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008.

- PMID 27444796.

- PMID 23897090.

- PMID 22089893.

- PMID 25880944.

- PMID 14580634.

- .

- S2CID 4509567.

- PMID 26769723.

- PMID 23153127.

- ^ "Guns and suicide: A fatal link". Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. 15 May 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- PMID 32492303.

- ISBN 978-0-309-09124-4.

- S2CID 35031090.

- ^ a b Miller, Matthew, Hemenway, David (2001). Firearm Prevalence and the Risk of Suicide: A Review. Harvard Health Policy Review. p. 2. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

One study found a statistically significant relationship between estimated gun ownership levels and suicide rate across 14 developed nations (e.g. where survey data on gun ownership levels were available), but the association lost its statistical significance when additional countries were included.

- PMID 11577914.

- .

- S2CID 72451364.

- .

- ^ S2CID 3275417.

- PMID 23975641.

- PMID 16751449.

- S2CID 27028514.

- S2CID 4756779.

- hdl:10419/214553.

- PMID 27196643.

- ISBN 978-0-19-513793-4.

- ^ Ikeda RM, Gorwitz R, James SP, Powell KE, Mercy JA (1997). Fatal Firearm Injuries in the United States, 1962–1994: Violence Surveillance Summary Series, No. 3. National Center for Injury and Prevention Control.

- S2CID 4509567.

- PMID 17170183.

- S2CID 35131214.

- PMID 18444777.

- PMID 15850034.

- S2CID 208623661.

- S2CID 9805679.

- PMID 32555647.

- ^ "Method Used in Completed Suicide". HKJC Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention, University of Hong Kong. 2006. Archived from the original on 10 September 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ^ "遭家人責罵:掛住上網媾女唔讀書 成績跌出三甲 中四生跳樓亡". Apple Daily. 9 August 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ^ a b c Anderson S (6 July 2008). "The Urge to End It". The New York Times.

- ISBN 978-1-85487-529-7.

- ^ Edward Robb Ellis, George N. Allen (1961). Traitor within: our suicide problem. Doubleday. p. 98.

- PMID 25939134.

- ^ a b c d International Parking & Mobility Institute (2019), Suicide in Parking Facilities: Prevention, Response, and Recovery (PDF)

- ^ PMID 31333923.

- ISBN 978-0-19-974870-9.

- PMID 15456551.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "The Gory Way Japanese Generals Ended Their Battle on Okinawa". Time. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- S2CID 46943176.

- ^ SSRN 1689049

- PMID 18566058.

- ^ Docker C, The Art and Science of Fasting in: Smith C, Docker C, Hofsess J, Dunn B, Beyond Final Exit 1995

- ^ Sundara A. "Nishidhi Stones and the ritual of Sallekhana" (PDF). International School for Jain Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Hinduism – Euthanasia and Suicide". BBC. 25 August 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-56718-336-8. Retrieved 4 February 2014 – via Google Books.

- S2CID 44883936.

- S2CID 36848946.

- S2CID 34734585.

- PMID 12878738.

- .

- ^ Smith WJ (12 November 2003). "A 'Painless' Death?". The Weekly Standard.

- ^ Ricardo Alonso-Zaldivar (26 January 2005). "Suicide by Train Is a Growing Concern". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- S2CID 46631419.

- ^ Evans L. "Driver behavior". Science Serving Society. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- PMID 22576104.

- S2CID 205884989.

- ^ "Glossary for transport statistics — 5th edition — 2019". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ Dinkel A, Baumert J, Erazo N, Ladwig KH (2011). "Jumping, lying, wandering: Analysis of suicidal behaviour patterns in 1,004 suicidal acts on the German railway net" (PDF). J. Psychiatr. Res. 45: 121–125. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- PMID 25939134.

- ^ PMID 16110685.

- PMID 27026123.

- ^ Clark N, Bilefsky D (26 March 2015). "Germanwings Co-Pilot Deliberately Crashed Airbus Jet, French Prosecutor Says". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Germanwings Flight 4U9525: Co-pilot put plane into descent, prosecutor says". CBC News. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Wescott R (16 April 2015). "Flight MH370: Could it have been suicide?". BBC News. BBC News. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ Pells R (23 July 2016). "MH370 pilot flew 'suicide route' on a simulator 'closely matching' his final flight". The Independent. The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- PMID 3985206.

- S2CID 21218263.

- ISBN 978-1-57230-541-0.

- PMID 10641944.

- ^ Liptak A (9 February 2008). "Electrocution Is Banned in Last State to Rely on It". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 February 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem (21 January 2011). "Slap to a Man's Pride Set Off Tumult in Tunisia". The New York Times. p. 2. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- from the original on 25 February 2024. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ Sophie Gilmartin (1997), The Sati, the Bride, and the Widow: Sacrificial Woman in the Nineteenth Century, Victorian Literature and Culture, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 25, No. 1, p. 141, Quote: "Suttee, or sati, is the obsolete Hindu practice in which a widow burns herself upon her husband's funeral pyre..."

- S2CID 79722611. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ Hughes R (1988). The Fatal Shore, The Epic Story of Australia's Founding (first ed.). Vintage Books.

Further reading

- Humphry D (1997). Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying. Dell. p. 240.

- ISBN 978-0-9788788-2-5.

- Docker C (2015). Five Last Acts - The Exit Path. Scotland: Createspace.

- Stone G (2001). Suicide and Attempted Suicide: Methods and Consequences. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-0940-3.