Suicide

| Suicide | |

|---|---|

| Prevention | Limiting access to methods of suicide, treating mental disorders and substance misuse, careful media reporting about suicide, improving social and economic conditions[2] |

| Frequency | 12 per 100,000 per year[6] |

| Deaths | 793,000 / 1.5% of deaths (2016)[7][8] |

| Suicide |

|---|

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own

The most commonly adopted

Approximately 1.5% of all deaths worldwide are by suicide.

Views on suicide have been influenced by broad existential themes such as religion, honor, and the meaning of life.

Definitions

Suicide, derived from Latin suicidium, is "the act of taking one's own life".[9][35] Attempted suicide or non-fatal suicidal behavior amounts to self-injury with at least some desire to end one's life that does not result in death.[36][37] Assisted suicide occurs when one individual helps another bring about their own death indirectly via providing either advice or the means to the end.[38] This is in contrast to euthanasia, where another person takes a more active role in bringing about a person's death.[38]

Suicidal ideation is thoughts of ending one's life but not taking any active efforts to do so.[36] It may or may not involve exact planning or intent.[37] Suicidality is defined as "the risk of suicide, usually indicated by suicidal ideation or intent, especially as evident in the presence of a well-elaborated suicidal plan."[39]

In a murder–suicide (or homicide–suicide), the individual aims at taking the lives of others at the same time. A special case of this is extended suicide, where the murder is motivated by seeing the murdered persons as an extension of their self.[40] Suicide in which the reason is that the person feels that they are not part of society is known as egoistic suicide.[41]

In 2011, in an article calling for changing the language used around suicide entitled "Suicide and language: Why we shouldn't use the 'C' word," the Centre for Suicide Prevention in Canada found that the normal verb in scholarly research and journalism for the act of suicide was commit, and argued for destigmatizing terminology related to suicide.

Risk factors

Factors that affect the risk of suicide include mental disorders, drug misuse,

Most research does not distinguish between risk factors that lead to thinking about suicide and risk factors that lead to suicide attempts.[64][65] Risks for suicide attempt rather than just thoughts of suicide include a high pain tolerance and a reduced fear of death.[66]

Mental illness

Mental illness is present at the time of suicide 27% to more than 90% of the time.

Others estimate that about half of people who die by suicide could be diagnosed with a personality disorder, with borderline personality disorder being the most common.[76] About 5% of people with schizophrenia die of suicide.[77] Eating disorders are another high risk condition.[78] Around 22% to 50% of people suffering with gender dysphoria have attempted suicide, however this greatly varies by region.[79][80][81][82][83]

Among approximately 80% of suicides, the individual has seen a

Substance misuse

Most people are under the influence of sedative-hypnotic drugs (such as alcohol or benzodiazepines) when they die by suicide,[89] with alcoholism present in between 15% and 61% of cases.[55] Use of prescribed benzodiazepines is associated with an increased rate of suicide and attempted suicide. The pro-suicidal effects of benzodiazepines are suspected to be due to a psychiatric disturbance caused by side effects, such as disinhibition, or withdrawal symptoms.[10] Countries that have higher rates of alcohol use and a greater density of bars generally also have higher rates of suicide.[90] About 2.2–3.4% of those who have been treated for alcoholism at some point in their life die by suicide.[90] Alcoholics who attempt suicide are usually male, older, and have tried to take their own lives in the past.[55] Between 3 and 35% of deaths among those who use heroin are due to suicide (approximately fourteenfold greater than those who do not use).[91] In adolescents who misuse alcohol, neurological and psychological dysfunctions may contribute to the increased risk of suicide.[92]

The misuse of

Previous attempts

A previous history of

Self-harm

Non-suicidal self-harm is common with 18% of people engaging in self-harm over the course of their life.[96]: 1 Acts of self-harm are not usually suicide attempts and most who self-harm are not at high risk of suicide.[97] Some who self-harm, however, do still end their life by suicide, and risk for self-harm and suicide may overlap.[97] Individuals who have been identified as self-harming after being admitted to hospital are 68% (38–105%) more likely to die by suicide.[98]: 279

Psychosocial factors

A number of psychological factors increase the risk of suicide including: hopelessness,

Certain personality factors, especially high levels of

Social isolation and the lack of social support has been associated with an increased risk of suicide.[99] Poverty is also a factor,[105] with heightened relative poverty compared to those around a person increasing suicide risk.[106] Over 200,000 farmers in India have died by suicide since 1997, partly due to issues of debt.[107] In China, suicide is three times as likely in rural regions as urban ones, partly, it is believed, due to financial difficulties in this area of the country.[108]

The time of year may also affect suicide rates. There appears to be a decrease around Christmas,[109] but an increase in rates during spring and summer, which might be related to exposure to sunshine.[37] Another study found that the risk may be greater for males on their birthday.[110]

Being religious may reduce one's risk of suicide while beliefs that suicide is noble may increase it.

Medical conditions

There is an association between suicidality and physical health problems such as

Sleep disturbances, such as

Occupational factors

Certain occupations carry an elevated risk of self-harm and suicide, such as military careers. Research in several countries has found that the rate of suicide among former armed forces personnel in particular,[121][122][123][124] and young veterans especially,[125][126][121] is markedly higher than that found in the general population.

Media

The media, including the Internet, plays an important role.[53][99] Certain depictions of suicide may increase its occurrence, with high-volume, prominent, repetitive coverage glorifying or romanticizing suicide having the most impact.[127] When detailed descriptions of how to kill oneself by a specific means are portrayed, this method of suicide can be imitated in vulnerable people.[17] This phenomenon has been observed in several cases after press coverage.[128][129] In a bid to reduce the adverse effect of media portrayals concerning suicide report, one of the effective methods is to educate journalists on how to report suicide news in a manner that might reduce that possibility of imitation and encourage those at risk to seek for help. When journalists follow certain reporting guidelines the risk of suicides can be decreased.[127] Getting buy-in from the media industry, however, can be difficult, especially in the long term.[127]

This trigger of suicide contagion or copycat suicide is known as the "Werther effect", named after the protagonist in Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther who killed himself and then was emulated by many admirers of the book.[130] This risk is greater in adolescents who may romanticize death.[131] It appears that while news media has a significant effect, that of the entertainment media is equivocal.[132][133] It is unclear if searching for information about suicide on the Internet relates to the risk of suicide.[134] The opposite of the Werther effect is the proposed "Papageno effect", in which coverage of effective coping mechanisms may have a protective effect. The term is based upon a character in Mozart's opera The Magic Flute—fearing the loss of a loved one, he had planned to kill himself until his friends helped him out.[130] As a consequence, fictional portrayals of suicide, showing alternative consequences or negative consequences, might have a preventive effect,[135] for instance fiction might normalize mental health problems and encourage help-seeking.[136]

Other factors

Trauma is a risk factor for suicidality in both children

Problem gambling is associated with increased suicidal ideation and attempts compared to the general population.[142] Between 12 and 24% of pathological gamblers attempt suicide.[143] The rate of suicide among their spouses is three times greater than that of the general population.[143] Other factors that increase the risk in problem gamblers include concomitant mental illness, alcohol, and drug misuse.[144]

Genetics might influence rates of suicide. A family history of suicide, especially in the mother, affects children more than adolescents or adults.[99] Adoption studies have shown that this is the case for biological relatives, but not adopted relatives. This makes familial risk factors unlikely to be due to imitation.[37] Once mental disorders are accounted for, the estimated heritability rate is 36% for suicidal ideation and 17% for suicide attempts.[37] An evolutionary explanation for suicide is that it may improve inclusive fitness. This may occur if the person dying by suicide cannot have more children and takes resources away from relatives by staying alive. An objection is that deaths by healthy adolescents likely does not increase inclusive fitness. Adaptation to a very different ancestral environment may be maladaptive in the current one.[101][145]

Infection by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii, more commonly known as toxoplasmosis, has been linked with suicide risk. One explanation states that this is caused by altered neurotransmitter activity due to the immunological response.[37]

There appears to be a link between

Rational

Euthanasia and assisted suicide are accepted practices in a number of countries among those who have a poor quality of life without the possibility of getting better.[148][149] They are supported by the legal arguments for a right to die.[149]

The act of taking one's life for the benefit of others is known as altruistic suicide.[150] An example of this is an elder ending his or her life to leave greater amounts of food for the younger people in the community.[150] Suicide in some Inuit cultures has been seen as an act of respect, courage, or wisdom.[151]

A

Methods

The leading method of suicide varies among countries. The leading methods in different regions include hanging, pesticide poisoning, and firearms.[18] These differences are believed to be in part due to availability of the different methods.[17] A review of 56 countries found that hanging was the most common method in most of the countries,[18] accounting for 53% of male suicides and 39% of female suicides.[161]

Worldwide, 30% of suicides are estimated to occur from pesticide poisoning, most of which occur in the developing world.[2] The use of this method varies markedly from 4% in Europe to more than 50% in the Pacific region.[162] It is also common in Latin America due to the ease of access within the farming populations.[17] In many countries, drug overdoses account for approximately 60% of suicides among women and 30% among men.[163] Many are unplanned and occur during an acute period of ambivalence.[17] The death rate varies by method: firearms 80–90%, drowning 65–80%, hanging 60–85%, jumping 35–60%, charcoal burning 40–50%, pesticides 60–75%, and medication overdose 1.5–4.0%.[17] The most common attempted methods of suicide differ from the most common methods of completion; up to 85% of attempts are via drug overdose in the developed world.[78]

In China, the consumption of pesticides is the most common method.[164] In Japan, self-disembowelment known as seppuku (harakiri) still occurs;[164] however, hanging and jumping are the most common.[165] Jumping to one's death is common in both Hong Kong and Singapore at 50% and 80% respectively.[17] In Switzerland, firearms are the most frequent suicide method in young males, although this method has decreased since guns have become less common.[166][167] In the United States, 50% of suicides involve the use of firearms, with this method being somewhat more common in men (56%) than women (31%).[168] The next most common cause was hanging in males (28%) and self-poisoning in females (31%).[168] Together, hanging and poisoning constituted about 42% of U.S. suicides (as of 2017[update]).[168]

Pathophysiology

There is no known unifying underlying pathophysiology for suicide;[23] it is believed to result from an interplay of behavioral, socio-economic and psychological factors.[17]

Low levels of

Prevention

Suicide prevention is a term used for the collective efforts to reduce the incidence of suicide through preventive measures. Protective factors for suicide include support, and access to therapy.[54] About 60% of people with suicidal thoughts do not seek help.[176] Reasons for not doing so include low perceived need, and wanting to deal with the problem alone.[176] Despite these high rates, there are few established treatments available for suicidal behavior.[99]

In young adults who have recently thought about suicide, cognitive behavioral therapy appears to improve outcomes.[180][99] School-based programs that increase mental health literacy and train staff have shown mixed results on suicide rates.[16] Economic development through its ability to reduce poverty may be able to decrease suicide rates.[105] Efforts to increase social connection, especially in elderly males, may be effective.[181] In people who have attempted suicide, following up on them might prevent repeat attempts.[182] Although crisis hotlines are common, there is little evidence to support or refute their effectiveness.[15][16] Preventing childhood trauma provides an opportunity for suicide prevention.[137] The World Suicide Prevention Day is observed annually on 10 September with the support of the International Association for Suicide Prevention and the World Health Organization.[183]

Screening

IS PATH WARM [...] is an acronym [...] to assess [...] a potentially suicidal individual, (i.e., ideation, substance abuse, purposelessness, anger, feeling trapped, hopelessness, withdrawal, anxiety, recklessness, and mood).[184]

— American Association of Suicidology (2019)

There is little data on the effects of screening the general population on the ultimate rate of suicide.

Mental illness

In those with mental health problems, a number of treatments may reduce the risk of suicide. Those who are actively suicidal may be admitted to psychiatric care either voluntarily or involuntarily.[23] Possessions that may be used to harm oneself are typically removed.[78] Some clinicians get patients to sign suicide prevention contracts where they agree to not harm themselves if released.[23] However, evidence does not support a significant effect from this practice.[23] If a person is at low risk, outpatient mental health treatment may be arranged.[78] Short-term hospitalization has not been found to be more effective than community care for improving outcomes in those with borderline personality disorder who are chronically suicidal.[189][190]

There is tentative evidence that

There is controversy around the benefit-versus-harm of

Epidemiology

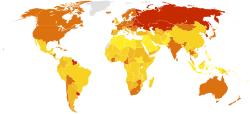

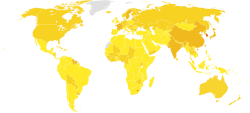

Approximately 1.4% of people die by suicide, a mortality rate of 11.6 per 100,000 persons per year.[6][23] Suicide resulted in 842,000 deaths in 2013 up from 712,000 deaths in 1990.[20] Rates of suicide have increased by 60% from the 1960s to 2012, with these increases seen primarily in the developing world.[3] Globally, as of 2008[update]/2009, suicide is the tenth leading cause of death.[3] For every suicide that results in death there are between 10 and 40 attempted suicides.[23]

Suicide rates differ significantly between countries and over time.[6] As a percentage of deaths in 2008 it was: Africa 0.5%, South-East Asia 1.9%, Americas 1.2% and Europe 1.4%.[6] Rates per 100,000 were: Australia 8.6, Canada 11.1, China 12.7, India 23.2, United Kingdom 7.6, United States 11.4 and South Korea 28.9.[202][203] It was ranked as the 10th leading cause of death in the United States in 2016 with about 45,000 cases that year.[204] Rates have increased in the United States in the last few years,[204] with about 49,500 people dying by suicide in 2022, the highest number ever recorded.[205] In the United States, about 650,000 people are seen in emergency departments yearly due to attempting suicide.[23] The United States rate among men in their 50s rose by nearly half in the decade 1999–2010.[206] Greenland, Lithuania, Japan, and Hungary have the highest rates of suicide.[6] Around 75% of suicides occur in the developing world.[2] The countries with the greatest absolute numbers of suicides are China and India, partly due to their large population size, accounting for over half the total.[6] In China, suicide is the 5th leading cause of death.[207]

An unofficial report estimated 5,000 suicides in Iran in 2022.[210]

Sex and gender

Globally as of 2012[update], death by suicide occurs about 1.8 times more often in males than females.[6][211] In the Western world, males die three to four times more often by means of suicide than do females.[6] This difference is even more pronounced in those over the age of 65, with tenfold more males than females dying by suicide.[212] Suicide attempts and self-harm are between two and four times more frequent among females.[23][213][214] Researchers have attributed the difference between suicide and attempted suicide among the sexes to males using more lethal means to end their lives.[212][215][216] However, separating intentional suicide attempts from non-suicidal self-harm is not currently done in places like the United States when gathering statistics at the national level.[217]

China has one of the highest female suicide rates in the world and is the only country where it is higher than that of men (ratio of 0.9).[6][207] In the Eastern Mediterranean, suicide rates are nearly equivalent between males and females.[6] The highest rate of female suicide is found in South Korea at 22 per 100,000, with high rates in South-East Asia and the Western Pacific generally.[6]

A number of reviews have found an increased risk of suicide among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people.[218][219] Among transgender persons, rates of attempted suicide are about 40% compared to a general population rate of 5%.[220][221] This is believed to in part be due to social stigmatisation.[222]

Age

In many countries, the rate of suicide is highest in the middle-aged[224] or elderly.[17] The absolute number of suicides, however, is greatest in those between 15 and 29 years old, due to the number of people in this age group.[6] Worldwide, the average age of suicide is between age 30 and 49 for both men and women.[225] This means that half of people who died by suicide were approximately age 40 or younger, and half were older.[225] Suicidality is rare in children, but increases during the transition to adolescence.[226]

In the United States, the suicide death rate is greatest in Caucasian men older than 80 years, even though younger people more frequently attempt suicide.

History

In

Suicide came to be regarded as a

Attitudes towards suicide slowly began to shift during the Renaissance. John Donne's work Biathanatos contained one of the first modern defences of suicide, bringing proof from the conduct of Biblical figures, such as Jesus, Samson and Saul, and presenting arguments on grounds of reason and nature to sanction suicide in certain circumstances.[233]

The secularization of society that began during the Enlightenment questioned traditional religious attitudes (such as Christian views on suicide) toward suicide and brought a more modern perspective to the issue. David Hume denied that suicide was a crime as it affected no one and was potentially to the advantage of the individual. In his 1777 Essays on Suicide and the Immortality of the Soul he rhetorically asked, "Why should I prolong a miserable existence, because of some frivolous advantage which the public may perhaps receive from me?"[233] Hume's analysis was criticized by philosopher Philip Reed as being "uncharacteristically (for him) bad", since Hume took an unusually narrow conception of duty and his conclusion depended upon the suicide producing no harm to others – including causing no grief, feelings of guilt, or emotional pain to any surviving friends and family – which is almost never the case.[234] A shift in public opinion at large can also be discerned; The Times in 1786 initiated a spirited debate on the motion "Is suicide an act of courage?".[235]

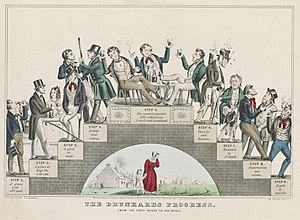

By the 19th century, the act of suicide had shifted from being viewed as caused by sin to being caused by insanity in Europe.[232] Although suicide remained illegal during this period, it increasingly became the target of satirical comments, such as the Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera The Mikado, which satirized the idea of executing someone who had already killed himself.

By 1879, English law began to distinguish between suicide and homicide, although suicide still resulted in forfeiture of estate.[236] In 1882, the deceased were permitted daylight burial in England[237] and by the middle of the 20th century, suicide had become legal in much of the Western world. The term suicide first emerged shortly before 1700 to replace expressions on self-death which were often characterized as a form of self-murder in the West.[230]

Social and culture

Legislation

No country in Europe currently considers suicide or attempted suicide to be a crime.[238] It was, however, in most Western European countries from the Middle Ages until at least the 19th century.[236] The Netherlands was the first country to legalize both physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia, which took effect in 2002, although only doctors are allowed to assist in either of them, and have to follow a protocol prescribed by Dutch law.[239] If such protocol is not followed, it is an offence punishable by law. In Germany, active euthanasia is illegal and anyone present during suicide may be prosecuted for failure to render aid in an emergency.[240] Switzerland has taken steps to legalize assisted suicide for the chronically mentally ill. The high court in Lausanne, Switzerland, in a 2006 ruling, granted an anonymous individual with longstanding psychiatric difficulties the right to end his own life.[241] England and Wales decriminalized suicide via the Suicide Act 1961 and the Republic of Ireland in 1993.[238] The word "commit" was used in reference to its being illegal, but many organisations have stopped it because of the negative connotation.[242][243]

In the United States, suicide is not illegal, but may be associated with penalties for those who attempt it.[238] Physician-assisted suicide is legal in the state of Washington for people with terminal diseases.[244] In Oregon, people with terminal diseases may request medications to help end their life.[245] Canadians who have attempted suicide may be barred from entering the United States. U.S. laws allow border guards to deny access to people who have a mental illness, including those with previous suicide attempts.[246][247]

In Australia, suicide is not a crime.

In India, suicide was illegal until 2014, and surviving family members used to face legal difficulties.[251][252] It remains a criminal offense in most Muslim-majority nations.[30]

In

Suicide became a trending crisis in North Korea in 2023; a secret order criminalized suicide as treason against socialist state.[257]

Religious views

Christianity

Most forms of Christianity consider suicide sinful, based mainly on the writings of influential Christian thinkers of the Middle Ages, such as

Judaism

Judaism focuses on the importance of valuing this life, and as such, suicide is tantamount to denying God's goodness in the world. Despite this, under extreme circumstances when there has seemed no choice but to either be killed or forced to betray their religion, there are several accounts of Jews having died by suicide, either individually or in groups (see

Islam

Islamic religious views are against suicide.[30] The Quran forbids it by stating "do not kill or destroy yourself".[264][265] The hadiths also state individual suicide to be unlawful and a sin.[30] Stigma is often associated with suicide in Islamic countries.[265]

Hinduism and Jainism

In Hinduism, suicide is generally disdained and is considered equally sinful as murdering another in contemporary Hindu society. Hindu Scriptures state that one who dies by suicide will become part of the spirit world, wandering earth until the time one would have otherwise died, had one not taken one's own life.[266] However, Hinduism accepts a man's right to end one's life through the non-violent practice of fasting to death, termed Prayopavesa;[267] but Prayopavesa is strictly restricted to people who have no desire or ambition left, and no responsibilities remaining in this life.[267]

Ainu

Within the

Philosophy

A number of questions are raised within the philosophy of suicide, including what constitutes suicide, whether or not suicide can be a rational choice, and the moral permissibility of suicide.[272] Arguments as to acceptability of suicide in moral or social terms range from the position that the act is inherently immoral and unacceptable under any circumstances, to a regard for suicide as a sacrosanct right of anyone who believes they have rationally and conscientiously come to the decision to end their own lives, even if they are young and healthy.

Opponents to suicide include philosophers such as Augustine of Hippo, Thomas Aquinas,[272] Immanuel Kant[273] and, arguably, John Stuart Mill – Mill's focus on the importance of liberty and autonomy meant that he rejected choices which would prevent a person from making future autonomous decisions.[274] Others view suicide as a legitimate matter of personal choice. Supporters of this position maintain that no one should be forced to suffer against their will, particularly from conditions such as incurable disease, mental illness, and old age, with no possibility of improvement. They reject the belief that suicide is always irrational, arguing instead that it can be a valid last resort for those enduring major pain or trauma.[275] A stronger stance would argue that people should be allowed to autonomously choose to die regardless of whether they are suffering. Notable supporters of this school of thought include Scottish empiricist David Hume,[272] who accepted suicide so long as it did not harm or violate a duty to God, other people, or the self,[234] and American bioethicist Jacob Appel.[241][276]

Advocacy

Advocacy of suicide has occurred in many cultures and

Internet searches for information on suicide return webpages that, in a 2008 study, about 50% of the time provide information on suicide methods. A similar study found that 11% of sites encouraged suicide attempts.[279] There is some concern that such sites may push those predisposed over the edge. Some people form suicide pacts online, either with pre-existing friends or people they have recently encountered in chat rooms or message boards. The Internet, however, may also help prevent suicide by providing a social group for those who are isolated.[280]

Locations

Some landmarks have become known for high levels of suicide attempts.

Notable cases

An example of

Thousands of Japanese civilians took their own lives in the last days of the Battle of Saipan in 1944, some jumping from "Suicide Cliff" and "Banzai Cliff".[291] The 1981 Irish hunger strikes, led by Bobby Sands, resulted in 10 deaths. The cause of death was recorded by the coroner as "starvation, self-imposed" rather than suicide; this was modified to simply "starvation" on the death certificates after protest from the dead strikers' families.[292] During World War II, Erwin Rommel was found to have foreknowledge of the 20 July plot on Hitler's life; he was threatened with public trial, execution, and reprisals on his family unless he killed himself.[293]

Other species

As suicide requires a willful attempt to die, some feel it therefore cannot be said to occur in non-human animals.[228] Suicidal behavior has been observed in Salmonella seeking to overcome competing bacteria by triggering an immune system response against them.[294] Suicidal defenses by workers are also noted in the Brazilian ant Forelius pusillus, where a small group of ants leaves the security of the nest after sealing the entrance from the outside each evening.[295]

There have been anecdotal reports of dogs, horses, and dolphins killing themselves,[299] but little scientific study of animal suicide.[300] Animal suicide is usually put down to romantic human interpretation and is not generally thought to be intentional. Some of the reasons animals are thought to unintentionally kill themselves include: psychological stress, infection by certain parasites or fungi, or disruption of a long-held social tie, such as the ending of a long association with an owner and thus not accepting food from another individual.[301]

See also

- Caring letters

- List of suicide crisis lines

- List of countries by suicide rate

- Prisoner suicide

- Substance-induced psychosis

- Youth suicide

References

- ^ ISBN 978-92-4-156477-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Suicide Fact sheet N°398". WHO. April 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ S2CID 208790312.

- S2CID 4549236.

- ^ S2CID 25741716.

- ^ PMID 22690161.

- ^ "Suicide across the world (2016)". World Health Organization. 27 September 2019. Archived from the original on 1 July 2004. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ S2CID 210332277.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-3390-8.

- ^ PMID 28257172.

- PMID 25859714.

- ^ "Suicide rates rising across the U.S. | CDC Online Newsroom | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 11 April 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

Relationship problems or loss, substance misuse; physical health problems; and job, money, legal or housing stress often contributed to risk for suicide.

- ISBN 978-92-4-159707-4.

- S2CID 58666001.

- ^ PMID 17824349.

Other suicide prevention strategies that have been considered are crisis centres and hotlines, method control, and media education... There is minimal research on these strategies. Even though crisis centres and hotlines are used by suicidal youth, information about their impact on suicidal behaviour is lacking.

- ^ PMID 27289303.

Other approaches that need further investigation include gatekeeper training, education of physicians, and internet and helpline support.

- ^ PMID 22726520.

- ^ PMID 18797649.

- PMID 27733281.. For the number 828,000, see Table 5, line "Self-harm", second column (year 2015)

- ^ PMID 25530442.. For the number 712,000, see Table 2, line "Self-harm", first column (year 1990)

- ^ "Suicide rates per (100 000 population)". World Health Organization.

- PMID 16946849.

- ^ PMID 22164363.

- ISBN 978-1-136-67690-1.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-9660-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4808-1124-9.

- ISBN 978-0-671-76071-7.

- ^ "Book excerptise: The Four Hundred Songs of War and Wisdom: An Anthology of Poems from Classical Tamil, the Purananuru by George L. (tr.) Hart and Hank Heifetz (tr.)". Department of Computer Science and Engineering, IIT Kanpur. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

Kapilar for King Pari #107 — When Vel Pari is killed in battle, kapilar is supposed to have committed suicide by vadakirrutal - facing North and starving.

- ISBN 978-1-84905-115-6.

- ^ S2CID 35754641.

- S2CID 35560934.

- PMID 27780435.

- ^ Vaughan M. "The 'discovery' of suicide in Africa". BBC. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Suicide". World Health Organization. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ Issues in Law & Medicine, Volume 3. National Legal Center for the Medically Dependent & Disabled, Incorporated, and the Horatio R. Storer Foundation, Incorporated. 1987. p. 39.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-4-154561-7.

- ^ PMID 26385066.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-306-47296-1.

- ^ "suicidality". APA Dictionary of Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. n.d. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-19-857005-9.

- ISBN 978-1-904671-44-2.

- ^ Olson R (2011). "Suicide and Language". Centre for Suicide Prevention. InfoExchange (3): 4. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Beaton S, Forster P, Maple M (February 2013). "Suicide and Language: Why we Shouldn't Use the 'C' Word". In Psych. 35 (1): 30–31. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014.

- ^ Inclusive Language Guidelines (PDF). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. p. 19. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-913486-13-9.

- ^ "Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide" (PDF). National Institute of Mental Health. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Reporting Suicide and Self Harm". Time To Change. 2008. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ @apstylebook (18 May 2017). "Avoid "committed suicide" except in direct quotes from authorities. Alternatives: "killed himself," "took her own life," "died by suicide."" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Guardian and Observer style guide: S". The Guardian. 4 May 2021.

- ^ Ravitz J (11 June 2018). "The words to say -- and not to say -- about suicide". CNN.

- ^ Ball PB (2005). "The Power of words". Canadian Association of Suicide Prevention. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- PMID 33270620.

- ^ S2CID 151486181.

- ^ a b "Suicide Risk and Protective Factors|Suicide|Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 April 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ S2CID 206143129.

- S2CID 24562104.

- PMID 22224886.

- S2CID 25133734.

- PMID 23636024.

- ISBN 978-1-111-18677-7. Archivedfrom the original on 3 October 2015.

- ^ PMID 22851956.

- ^ PMID 18439442.

- ^ a b c d "Suicide Risk and Protective Factors|Suicide|Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 April 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- S2CID 35079333.

- PMID 24313594.

- S2CID 21053071.

- ^ a b University of Manchester Centre for Mental Health and Risk. "The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- PMID 29879094.

- PMID 15527502.

- ^ PMID 11097952.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-119-95311-1.

- S2CID 27142497.

- S2CID 13331602.

- PMID 25875222.

- S2CID 10644601.

- S2CID 54280127.

Between 40% and 65% of individuals who commit suicide meet criteria for a personality disorder, with borderline personality disorder being the most commonly associated.

- S2CID 208792724. Archived from the original(PDF) on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-148480-0.

- ^ Cheung A, Zwickl S (23 March 2021). "Why have nearly half of transgender Australians attempted suicide?". Pursuit. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Transgender people and suicide". Centre for Suicide Prevention. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- PMID 35043256.

- ^ "Suicide risk in transgender and gender diverse people". National Elf Service. 13 July 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Study Shows Shocking Rates of Attempted Suicide Among Trans Teens". Human Rights Campaign. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ S2CID 43144463.

- PMID 12042175.

- PMID 26819231.

- ISBN 978-0-7657-0289-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-3669-5.

- PMID 18633742.

- ^ PMID 16287907.

- S2CID 11619947.

- S2CID 42672912.

- S2CID 39592475.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-2468-5.

- ^ PMID 18676099.

- PMID 26401305.

- ^ PMID 19826208.

- S2CID 3428927.

- ^ PMID 26360404.

- S2CID 7093281.

- ^ S2CID 42500507.

- PMID 21369952.

- PMID 24166408.

- S2CID 23574459.

- ^ PMID 21702640.

- (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2012.

- ^ Lerner G (5 January 2010). "Activist: Farmer suicides in India linked to debt, globalization". CNN World. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- S2CID 24474367.

- PMID 15496706.

- PMID 21616762.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2015.

- ISBN 978-0521603676.

Concerning suicide rates, religious nations fare better than secular nations. According to the 2003 World Health Organization's report on international male suicides rates, of the top ten nations with the highest male suicide rates, all but one (Sri Lanka) are strongly irreligious nations with high levels of atheism. Of the top remaining nine nations leading the world in male suicide rates, all are former Soviet/Communist nations, such as Belarus, Ukraine, and Latvia. Of the bottom ten nations with the lowest male suicide rates, all are highly religious nations with statistically insignificant levels of organic atheism.

- PMID 20197256.

- S2CID 23697880.

- from the original on 10 September 2011.

- ^ S2CID 45874503.

- PMID 34070367.

- ISBN 978-962-209-943-2.

- PMID 22032872.

- PMID 16268383.

- ^ a b Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (29 September 2021). "Serving and ex-serving Australian Defence Force members who have served since 1985: suicide monitoring 2001 to 2019". aihw.gov.au. Archived from the original on 26 August 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ Department of National Defence (11 May 2022). "2021 Report on Suicide Mortality in the Canadian Armed Forces (1995 to 2020)". www.canada.ca. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Simkus K, Hall A, Heber A, VanTil L (18 June 2020). "Veteran Suicide Mortality Study: Follow-up period from 1976 to 2014". Ottawa, ON: Veterans Affairs Canada. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ US Department of Veterans Affairs (Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention) (September 2021). "2001-2019 National Suicide Data Appendix". va.gov. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- PMID 19260757.

- S2CID 233313427. Archived from the original(PDF) on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ S2CID 1262883.

- PMID 17630375.

- PMID 2652386.

- ^ PMID 22470283.

- S2CID 21353878.

- .

- ISBN 978-1-61470-965-7.

- S2CID 26744237.

- S2CID 22599053.

- ISSN 0163-4437.

- ^ PMID 28483301.

- S2CID 1512121.

- S2CID 25054003.

- PMID 20007747.

- S2CID 232065964.

- ISBN 978-1-58562-136-1.

- ^ PMID 18461253.

- PMID 18202728.

- PMID 20141266.

- PMID 31850801.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-387-33753-1.

- PMID 29719381.

- ^ PMID 28210521.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4129-6966-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-58562-414-0.

- ISBN 978-90-481-3658-2.

- PMID 19767502.

- ISBN 978-1-111-30157-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-515221-0.

- ISBN 978-0-86720-974-7.

- ISBN 978-0-415-32773-2.

- ISBN 978-0-253-20884-2.

- PMID 11111261.

Table 1

- PMID 26551975.

- ISBN 978-1-119-99856-3.

- PMID 18154668.

- ISBN 978-0-19-923396-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-4-154561-7.

- PMID 25373686.

- S2CID 8405876.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-0581-4. Archivedfrom the original on 3 October 2015.

- ^ a b c "Suicide – Mental Health Statistics". National Institute of Mental Health. April 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- PMID 23114813.

- S2CID 25684743.

- PMID 21051476.

- PMID 22078480.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4398-3881-5.

- ISBN 978-1-904671-44-2.

- PMID 19833253.

- ^ PMID 21263012.

- ^ a b "Suicide prevention". WHO Sites: Mental Health. World Health Organization. 31 August 2012. Archived from the original on 1 July 2004. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- S2CID 35738851.

- PMID 23496989.

- S2CID 24708914.

- PMID 22690159.

- S2CID 25181980.

- ^ "World Suicide Prevention Day −10 September, 2013". IASP. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ Young M (2020). "Assessment and Goal Setting". Learning the Art of Helping: Building Blocks and Techniques. Pearson. p. 195.

[And] was developed by the American Association of Suicidology (2019) to gauge suicidal risk (see also Juhnke, Granello, & Lebrón-Striker, 2007)

- S2CID 8881023.

- PMID 24842417.

- ISBN 978-0-495-81167-1.

- PMID 19617829.

- S2CID 28921269.

- S2CID 7261201.

- PMID 22977392.

- PMID 22895952.

- PMID 23609101.

- PMID 23152227.

- PMID 12720484.

- PMID 23814104.

- PMID 12665398.

- PMID 25982932.

- ^ Caldwell BE (September–October 2013). "Whose Conscience Matters?" (PDF). Family Therapy Magazine (page 22). American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ BELLAH v. GREENSON (Court case). 6 June 1978. Retrieved 22 January 2018 – via Findlaw.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ a b Fox K, Shveda K, Croker N, Chacon M (26 November 2021). "How US gun culture stacks up with the world". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 December 2023. Article updated October 26, 2023. CNN cites data source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global Burden of Disease 2019), UN Population Division.

- ^ "Deaths estimates for 2008 by cause for WHO Member States". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Suicide rates Data by country". who.int. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ a b "Suicide rates rising across the U.S." CDC Newsroom. 7 June 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ "Suicides in the U.S. reached all-time high in 2022, CDC data shows". NBC News. 10 August 2023. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ "CDC finds suicide rates among middle-aged adults increased from 1999 to 2010". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2 May 2013. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ PMID 20454475.

- ^ "Death rate from suicides". Our World in Data. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ "Share of deaths from suicide". Our World in Data. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ "میزان خودکشی در ایران طی یک دهه گذشته، بیش از ۴۰درصد رشد کرده". etemadonline.com (in Persian). Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ "Estimates for 2000–2012". WHO. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-111-83459-3. Archivedfrom the original on 30 October 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-323-32899-9. Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2016.

- ISBN 978-92-4-154561-7. Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2016.

- ISBN 978-81-321-0499-5. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-136-87493-2. Archivedfrom the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ "Suicide Statistics". American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). 16 February 2016. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- PMID 21213174.

- ^ "Suicide Attempts among Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Adults" (PDF). January 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- S2CID 149086762.

- PMID 28031583.

- ^ "Reports" (PDF). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ "Suicide rates by age". Our World in Data. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ S2CID 193711.

- ^ a b "Summary tables of mortality estimates by cause, age and sex, globally and by region, 2000–2016". World Health Organization. 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- S2CID 199380438.

- ISBN 978-0-275-96646-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-57230-541-0.

- ISBN 978-0-495-81018-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-6647-0.

- ISBN 978-0-415-20582-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2 April 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-57230-541-0.

- ^ a b Suicide. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-000-21674-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4051-5450-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8014-8425-4. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-58798-113-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-470-51241-8.

- ^ "Dutch 'mercy killing law' passed". 11 April 2001. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "German politician Roger Kusch helped elderly woman to die". Times Online. 2 July 2008. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010.

- ^ S2CID 28038414.

- ^ Holt, Gerry."When suicide was illegal" Archived 7 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 3 August 2011. Accessed 11 August 2011.

- ^ "Guardian & Observer style guide". Guardian website. The Guardian. 31 December 2015. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Chapter 70.245 RCW, The Washington death with dignity act". Washington State Legislature. Archived from the original on 8 July 2010.

- Oregon State Legislature. Archivedfrom the original on 7 October 2015.

- ^ "CBCNews.ca Mobile". Cbc.ca. 1 February 1999. Archived from the original on 7 August 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ Adams C (15 April 2014). "US border suicide profiling must stop: Report". globalnews.ca. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-86287-558-6.

- ISBN 978-1-86287-060-4.

- ISBN 978-0-89789-921-5.

- ISBN 978-81-7993-412-8. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Govt decides to repeal Section 309 from IPC; attempt to suicide no longer a crime". Zee News. 10 December 2014. Archived from the original on 15 May 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ "Why so long to decriminalise suicide, says Befrienders". Free Malaysia Today. 19 June 2022.

- Channel News Asia. 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Malaysia's Pathway to the Decriminalisation of Suicides: Students' Opinion and Discussions (pdf)". academia.edu. 27 December 2020.

- ^ "As decriminalisation nears, a brief look at how suicide became a crime in Malaysia". Malay Mail. 7 April 2023.

- ^ Zitser J. "Kim Jong Un orders North Koreans to stop killing themselves after number of suicides skyrocketed". Business Insider. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Roth R. "Suicide & Euthanasia – a Biblical Perspective". Acu-cell.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ "Norman N. Holland, Literary Suicides: A Question of Style". Clas.ufl.edu. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ "Is suicide a sin?". 28 October 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – Part 3 Section 2 Chapter 2 Article 5". Scborromeo.org. 1 June 1941. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – Part 3 Section 2 Chapter 2 Article 5". Scborromeo.org. 1 June 1941. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ "Euthanasia and Judaism: Jewish Views of Euthanasia and Suicide". ReligionFacts.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ "Surah An-Nisa - 29". Quran.com. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ S2CID 30494312.

- ^ Hindu Website. Hinduism and suicide Archived 7 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Hinduism – Euthanasia and Suicide". BBC. 25 August 2009. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009.

- ^ "India wife dies on husband's pyre". 22 August 2006. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Takako Yamada: The Worldview of the Ainu. Nature and Cosmos Reading from Language, p. 25–37, p. 123.

- ^ Norbert Richard Adami: Religion und Schaminismus der Ainu auf Sachalin (Karafuto), Bonn 1989, p. 45.

- ^ a b Adami: Religion und Schaminismus der Ainu auf Sachalin (Karafuto), p. 79, p. 119.

- ^ a b c "Suicide". Suicide (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Plato.stanford.edu. 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-521-56673-5. p. 177.

- PMID 9762538.

- ISBN 0-313-31474-8.

- ^ Smith WJ (August 2007). "Death on Demand: The assisted-suicide movement sheds its fig leaf". NRL News. 34 (8): 18. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- The Walters Art Museum. Archivedfrom the original on 16 January 2013.

- S2CID 145475668.

- PMID 22401525.

- PMID 22073021.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4094-2133-7.

- ^ "A voice of reason on Yangtze bridge". The National. 8 July 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ISBN 978-1-84593-684-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-46841-1.

- ISBN 978-0-415-49913-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-34851-8.

- ISBN 978-1-60623-997-1.

- ^ Hall 1987, p.282

- ^ "Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple". San Diego State University. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "1978:Mass Suicide Leaves 900 Dead Archived 2012-11-04 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945, Random House, 1970, p. 519

- S2CID 154281192.

- ISBN 978-0-8117-3381-6.

- ^ Chang K (25 August 2008). "In Salmonella Attack, Taking One for the Team". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017.

- (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2009.

- ^ O'Hanlon L (10 March 2010). "Animal Suicide Sheds Light on Human Behavior". Discovery News. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010.

- ^ S2CID 19770804.

- ^ "Life In The Undergrowth". BBC.

- ^ Nobel J (19 March 2010). "Do Animals Commit Suicide? A Scientific Debate". Time. Archived from the original on 22 March 2010.

- S2CID 31876340.

- ^ Hogenboom M (6 July 2016). "Many animals seem to kill themselves, but it is not suicide". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

Further reading

- Gambotto A (2004). ISBN 978-0-9751075-1-5.

- Goeschel C (2009). Suicide in Nazi Germany. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953256-8.

External links

- Suicide at Curlie

- Preventing suicide: a global imperative (PDF). WHO. 2014. ISBN 978-92-4-156477-9.

- Freakonomics podcast: The Suicide Paradox

![Death rate from suicide per 100,000 as of 2017[208]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/01/Death_rate_from_suicides_%28IHME_%281990_to_2016%29%29%2C_OWID.svg/312px-Death_rate_from_suicides_%28IHME_%281990_to_2016%29%29%2C_OWID.svg.png)

![Share of deaths from suicide, 2017[209]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6a/Share_of_deaths_from_suicide%2C_OWID.svg/312px-Share_of_deaths_from_suicide%2C_OWID.svg.png)