History of Sumer

The history of Sumer spans the 5th to 3rd millennia BCE in southern

The oldest known settlement in southern

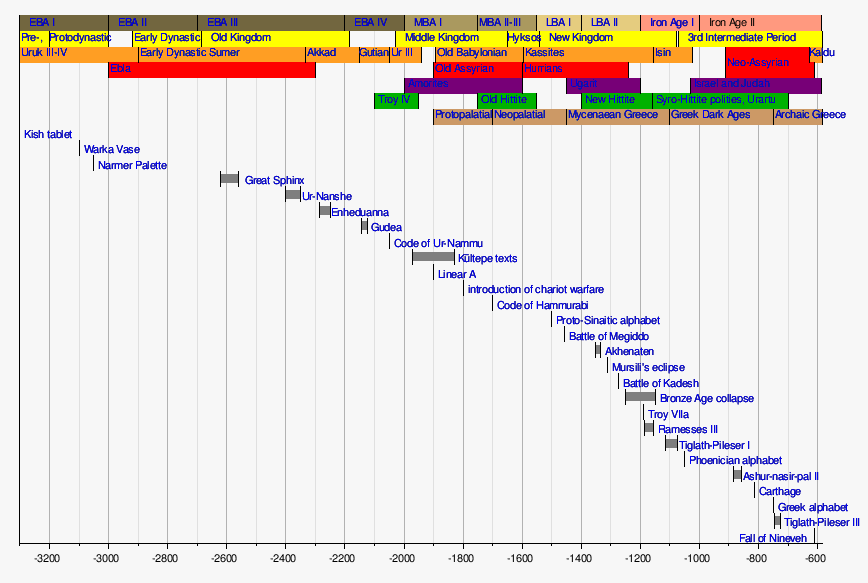

Timeline

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Uruk III = Jemdet Nasr period

Earliest city-states

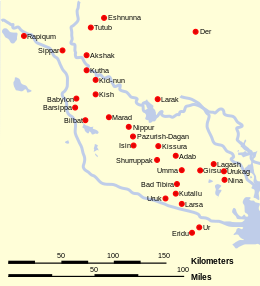

Permanent year-round urban settlement may have been prompted by intensive agricultural practices. The work required in maintaining irrigation canals called for, and the resulting surplus food enabled, relatively concentrated populations. The centres of Eridu and Uruk, two of the earliest cities, had successively elaborated large temple complexes built of mud brick. Developing as small shrines with the earliest settlements, by the Early Dynastic I period, they had become the most imposing structures in their respective cities, each dedicated to its own respective god. From south to north, the principal temple-cities, their principal temple complex, and the gods they served,[1] were

- Eridu, E-Abzu, Enki

- Ur, E-kishnugal, Nanna (moon)

- Utu(sun)

- An

- Inana

- Ningirsu

- Zabalam)

- E-kur, Enlil

- Shuruppak, E-dimgalanna, Sud (variant of Ninlil, wife of Enlil)

- Marad, E-igikalamma, Lugal-Marada (variant of Ninurta)

- Kish, ?, Ninhursag

- Utu(sun)

- Kutha, E-meslam, Nergal

Before 3000 BCE the political life of the city was headed by a priest-king (

Relative stratigraphy chronology

- A : c. 3400 BCE : numerical tablet; B : c. 3300 BCE : numerical tablet with logograms;

C : c. 3240 BCE : script (phonograms); D : c. 3000 BCE : lexical script

- A : c. 3400 BCE : numerical tablet; B : c. 3300 BCE : numerical tablet with logograms;

History

Pre- and protohistory

The pre- and protohistory of southern Mesopotamia is divided into the Ubaid (c. 6500–3800 BC), Uruk (c. 4000 to 3100 BC) and Jemdet Nasr (c. 3100 to 2900 BC) periods. There is scholarly disagreement as to when the Sumerian presence began in the region, although it is generally assumed that the Sumerian language was used in southern Mesopotamia by the late Uruk period. Some scholars believe that the Sumerians migrated to the area as late as c. 3600 BC, whereas others believe that the Sumerian presence goes back to the early Ubaid period or even prior to that.[13]

Early Dynastic period

The Early Dynastic Period began after a cultural break with the preceding Jemdet Nasr period that has been radio-carbon dated to about 2900 BC at the beginning of the Early Dynastic I Period. No inscriptions have yet been found verifying any names of kings that can be associated with the Early Dynastic I period. The ED I period is distinguished from the ED II period by the narrow cylinder seals of the ED I period and the broader wider ED II seals engraved with banquet scenes or animal-contest scenes.

Hegemony, which came to be conferred by the Nippur priesthood, alternated among a number of competing dynasties, hailing from Sumerian city-states traditionally including Kish, Uruk, Ur, Adab and Akshak, as well as some from outside of southern Mesopotamia, such as Awan, Hamazi, and Mari, until the Akkadians, under Sargon of Akkad, overtook the area.

First Dynasty of Kish

The earliest Dynastic name on the list known from other legendary sources is

First Dynasty of Uruk

First Dynasty of Ur

This dynasty is dated to the 26th century BC.

Dynasty of Awan

This dynasty is dated to the 26th century BC, about the same time as Elam is also mentioned clearly.[22] According to the Sumerian king list, Elam, Sumer's neighbor to the east, held the kingship in Sumer for a brief period, based in the city of Awan.

Second Dynasty of Uruk

Enshakushanna was a king of Uruk in the later 3rd millennium BC who is named on the Sumerian king list, which states his reign to have been 60 years. He was succeeded in Uruk by Lugal-kinishe-dudu, but the hegemony seems to have passed briefly to Eannatum of Lagash.

Empire of Lugal-Ane-mundu of Adab

Following this period, the region of Mesopotamia seems to have come under the sway of a Sumerian conqueror from Adab,

Kug-Bau and the Third Dynasty of Kish

The Third Dynasty of Kish, represented solely by

Dynasty of Akshak

Akshak too achieved independence with a line of rulers extending from Puzur-Nirah, Ishu-Il, and Shu-Suen, son of Ishu-Il, before being defeated by the rulers in the Fourth Dynasty of Kish.

First Dynasty of Lagash

This dynasty is dated to the 25th century BC.[.

His son and successor Entemena restored the prestige of Lagash.[24] Illi of Umma was subdued, with the help of his ally Lugal-kinishe-dudu or Lugal-ure of Uruk, successor to Enshakushana and also on the king-list. Lugal-kinishe-dudu seems to have been the prominent figure at the time, since he also claimed to rule Kish and Ur. A silver vase dedicated by Entemena to his god is now in the Louvre.[24] A frieze of lions devouring ibexes and deer, incised with great artistic skill, runs round the neck, while the eagle crest of Lagash adorns the globular part. The vase is a proof of the high degree of excellence to which the goldsmith's art had already attained.[24] A vase of calcite, also dedicated by Entemena, has been found at Nippur.[24] After Entemena, a series of weak, corrupt priest-kings is attested for Lagash. The last of these, Urukagina, was known for his judicial, social, and economic reforms, and his may well be the first legal code known to have existed.

Empire of Lugal-zage-si of Uruk

Urukagina (c. 2359–2335 BC

Akkadian Empire

| Sargon | c. 2334–2279 BC | |

| Rimush | c. 2278–2270 BC | younger son of Sargon |

Man-ishtishu |

c. 2269–2255 BC | elder son of Sargon |

| Naram-Sin | c. 2254–2218 BC | son of Man-ishtishu |

Shar-kali-sharri |

c. 2217–2193 BC | son of Naram-Suen |

Irgigi |

||

| Imi | ||

Nanum |

||

| Elulu | ||

Dudu |

c. 2189–2168 BC | |

Shu-Durul |

c. 2168–2147 BC | Akkad defeated by the Gutians |

Gutian period

Following the fall of Sargon's Empire to the Gutians, a brief "Dark Ages" ensued. This period lasted c. 2141–2050 BC (short chronology).

Second Dynasty of Lagash

This period lasted c. 2260–2110 BC.[citation needed]

| Ki-Ku-Id | ||

| Engilsa | ||

| Ur-A | ||

Lugalushumgal |

||

| Puzer-Mama | c. 2200 BC | contemporary of Shar-kali-sharri of Akkad

|

| Ur-Utu | ||

| Ur-Mama | ||

| Lu-Baba | ||

| Lugula | ||

| Kaku or Kakug | ||

Ur-baba |

c. 2093–2080 BC (short) | |

| Gudea | c. 2080–2060 BC | son-in-law of Ur-baba |

| Ur-Ningirsu | c. 2060–2055 BC | son of Gudea |

| Pirigme or Ugme | c. 2055–2053 BC | |

| Ur-gar | c. 2053–2049 BC | |

Nammahani |

c. 2049–2046 BC | grandson of Kaku, defeated by Ur-Nammu |

Fifth Dynasty of Uruk

This dynasty lasted between c. 2055–2048 BC

Third Dynasty of Ur

The

After the Ur III dynasty was destroyed by the Elamites in 2004 BC, a fierce rivalry developed between the city-states of Larsa, more under Elamite than Sumerian influence, and

During the third millennium BC, there developed a very intimate cultural symbiosis between the Sumerians and the Akkadians, which included widespread bilingualism.[26] The influence of Sumerian on Akkadian (and vice versa) is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a massive scale, to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence.[26] This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian in the third millennium as a sprachbund.[26]

Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as the spoken language of Mesopotamia somewhere around the turn of the third and the second millennium BC (the exact dating being a matter of debate),[27] but Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary and scientific language in Mesopotamia until the first century AD.

See also

References

- ^ George, Andrew (1993), House Most High. The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild (Ed) (1939),"The Sumerian King List" (Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago; Assyriological Studies, No. 11.)

- ^ Harriet Crawford. Sumer and the Sumerians. 2004. Page 28

- ^ Cuneiform. By C. B. F. Walker.

- ^ Records of the Past, Volume 5, Issue 11. Edited by Henry Mason Baum, Frederick Bennett Wright, George Frederick Wright. Records of the Past Exploration Society., 1906. Pg 352.

- ^ The Adaptation of Cuneiform to Akkadian Archived 2013-08-23 at the Wayback Machine Piotr Michalowski University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

- ^ Western Civilization: Beyond Boundaries. Cengage Learning, Jan 1, 2008. pages 12–13.

- ^ Christopher Woods. Associate Professor of Sumerian. http://nelc.uchicago.edu/faculty/woods Archived 2013-04-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-1-885923-76-9, archived from the original(PDF) on 2021-08-26, retrieved 2013-07-19

- Alex de Voogt, Joachim Friedrich Quack. BRILL, Dec 9, 2011. Page 181 Archived 2023-11-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Drs. T.J.H. (Theo) Krispijn - Assyriology - Faculty of Humanities http://www.hum.leiden.edu/lias/organisation/assyriology/krispijntjh.html Archived 2013-05-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ via Dietrich Sürenhagen (1999)

- ISBN 978-1-315-51116-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-07-27. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ^ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, page 129

- ^ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, p. 502

- ^ Roux, Georges 1971, "Ancient Iraq", Penguin, Harmondsworth.

- ISBN 978-1-58839043-1.

- ^ "Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin". Repository. Edition Topoi. Archived from the original on 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- Nimrodthe Hunter, mentioned in the Bible as founding Erech

- ^ "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". ETCSL. UK: Oxford. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ISBN 9780521070515.

- ISBN 1107094690p79

- ^ Samuel Kramer, The Sumerians, 51-52.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Sayce, Archibald Henry; King, Leonard William; Jastrow, Morris (1911). "Babylonia and Assyria". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–112.

- ^ "Hash-hamer Cylinder seal of Ur-Nammu". British Museum. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-953222-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-04-18. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ a b Woods C. 2006 "Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian". In S. L. Sanders (ed) Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture: 91–120 Chicago [1] Archived 2013-04-29 at the Wayback Machine