Romania in Antiquity

| History of Romania |

|---|

|

|

|

The Antiquity in Romania spans the period between the foundation of

Archaeological research prove that

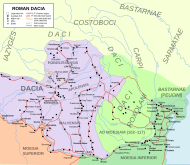

Modern Dobruja—the territory between the Lower Danube and the Black Sea—was the first historical region of Romania to have been incorporated in the Roman Empire. The region was attached to the Roman province of Moesia between 46 and 79 AD. The Romans also occupied Banat, Oltenia and Transylvania after the fall of Decebalus and the disintegration of his kingdom in 106. The three regions together formed the new province of Dacia. The new province was surrounded by "barbarian" tribes, including the Costoboci, the Iazyges and the Roxolani. New Germanic tribes—the Buri and the Vandals—arrived and settled in the vicinity of Dacia province in the course of the Marcomannic Wars in the second half of the 2nd century.

Background

The antrophomorphic figurines of the "

Practically nothing is known of the languages spoken by the locals in this period.[7] Historians—for instance, Vlad Georgescu and Mihai Rotea—say that the spread of Indo-European languages began in the period between 2500 and 2000 BC.[5][8][6] Fortified settlements and the great number of weapons—arrowheads, spears and knife blades—unearthed in them show that the stability featuring the Stone Age cultures of "Old Europe" came to an end in the same period.[8]

Coexistence of a great number of transitory cultures, including the "

Before the Romans

Greek colonies

Inscriptions from Histria and Callatis prove that the townsfolk preserved their ancestral traditions for more than half a millennium.[21][22] They maintained the ancient denominations for their tribes, magistrates, and public bodies, and remained faithful to cults taken from the motherland.[16] The three colonies developed into important centers of trade in olive oil, wine, fine pottery and jewelry.[14][23] A level of houses and temples destroyed proves that an unidentified enemy—according to the scholar Paul MacKendrick, Scythians—took and sacked Histria in the late 6th century BC.[24]

Initially, the constitution of Histria was an oligarchy, but, as Aristotle recorded, "it ended in the rule of the populace".[25][26] MacKendrick writes that this change from the rule of aristocratic families to democracy occurred around 450 BC.[27] Thereafter an assembly and council administered Histria; their members were elected by the free male citizens of the town.[27] Callatis also became a democracy in the second half of the 5th century BC.[28] According to MacKendrick, the fragment "KA…" in an inscription listing the Greek towns paying tribute to Athens refers to Callatis, proving that the town became a member of the Delian League.[29]

For defensive purposes, both Histria and Callatis were surrounded by walls: the former in the 4th and 2nd centuries BC, the latter in the 4th century BC.[30] King Lysimachus of Thrace forced Histria to accept his suzerainty in the 310s BC, and Celts sacked the town in 279 BC.[31] Histria and Callatis attempted to take the port of Tomis, but they were defeated around 262 BC.[20]

Getae

The natives of the Lower Danube region came to the attention of classical authors after the establishment of Greek colonies along the Black Sea shore.

The "Ferigile-Bârseşti" group of cremation

The "Getae beyond

After Alexander the Great's death, Lysimachus of Thrace ruled the northern regions of the

Syginnae

The Syginnae, who had "small, short-faced, long-haired horses",

Agathyrsi

Herodotus writes that the

Quivers decorated with metal crosses, mirrors and other featuring artifacts of the "Agathyrsian territory" appeared in the easternmost regions of the plains along the River Tisa around 500 BC, suggesting that the Agathyrsi expanded their rule over these territories in the subsequent century.[56] Although Aristotle in his Problems still referred to the Agathyrsi, stating that they "sang their laws, so as not to forget them",[57] thereafter no written source makes mention of them.[56] Their cemeteries ceased to be used around 350 BC.[56] Whether the Agathyrsi were assimilated by other tribes, or abandoned their lands, cannot be decided.[56][36]

Celts

In the period between 450 and 200 BC, the vast territory between the

"La Tène" settlements were consisted of semi-sunken huts, each with a nearby storage pit.[61] Large "La Tène" cemeteries were unearthed, for instance, at

Bastarnae

The Bastarnae settled in the region between the rivers

Rustoiu identifies the Bastarnae as the bearers of the "Poieneşti–Lukašovka culture" of the regions to the east of the Carpathian Mountains,[65] but this identification is not universally accepted.[66] For instance, "Poieneşti–Lukašovka" settlements were inhabited by a sedentary population,[65] but the historian Malcolm Todd says that the mobility of the Bastarnic warriors suggests that they were mustered by a nomad or semi-nomad people.[66] Besides ceramics featuring the culture, "Poieneşti–Lukašovka" sites yielded pottery with analogies in Dacian and Celtic sites.[65]

Towards Roman occupation

Greek colonies

Callatis, Histria and Tomis accepted the suzerainty of King

The three towns made an anti-Roman alliance with the Bastarnae, the Getae and other "barbarian" tribes in 61 BC.[68] They inflicted a decisive defeat on the Roman armies which were under the command of Gaius Antonius Hybrida, Proconsul of Macedonia.[70] King Burebista of the Dacians subjugated the three Greek colonies in about 50 BC.[71][72] An inscription from the same time refers to the "second founding" of Histria, implying that it had been nearly destroyed during the previous wars.[73]

Callatis, Histria and Tomis regained their freedom after the death of Burebista in 44 BC.[73] However, their independence became nominal and they accepted Roman protectorate after the expedition of 27 BC by Marcus Licinius Crassus in the lands between the Lower Danube and the Black Sea.[73] The Roman poet, Ovid spent his last years in exile in Tomis between 9 and 17 AD.[73] His poems evidence that barbarian attack was a constant menace for the townsfolk in this period.[74]

Would you care to learn the nature of the local inhabitants,

find out amid what customs I survive?

They're a mixed stock, Greek and native, but the natives –

still barely civilized – prevail.

Great hordes of tribal nomads – Sarmatians, Getae –

come riding in and out here, hog the crown

of the road, every one of them carrying bow and quiver

and poisoned arrows, yellow with viper's gall:

harsh voices, fierce faces, warriors incarnate,

hair and beards shaggy, untrimmed,

hands not slow to draw – and drive home – the sheath knife

that each barbarian wears strapped at his side.

Dacians

The earliest records of the Dacians are connected to their conflicts with the Roman Empire in the 2nd century BC.[76][77] Strabo writes, in his Geographica, that their language "is the same as that of the Getae".[78][76] He adds that the distinction between the Getae and the Dacians is based on their location: the Getae are "those who incline towards the Pontus and the east," and the Dacians are "those who incline in the opposite direction towards Germany and the sources of the Ister".[78][79]

Archaeological finds—cremation graves yielding horse bits, curved daggers or sica, swords and other weapons—evidence the development of a military elite in the territories to the north of the Lower Danube in the 3rd-1st centuries BC.[80] Tumuli with similar grave goods appeared in the same region and expanded towards southwest Transylvania and southern Moldavia from around 100 BC.[81] The military character of the new elite is proven by the frequent raids against the neighboring territories, primarily in Thrace and Macedonia, from the 110s BC, which provoked counter-attacks by the Romans.[82][77] For instance, Frontinus writes of Marcus Minucius Rufus's victory over "the Scordiscans and Dacians"[83] in 109 BC, and Florus says that Gaius Scribonius Curio, Proconsul of Macedonia "reached Dacia, but shrank from its gloomy forests"[84] in 74 BC.[82][77]

The native tribes of the wider region of the Lower Danube were for the first time united under King

Strabo writes that Burebista "had as his coadjutor

Strabo writes that Burebista "was deposed"[90] during an uprising.[93] The year of Burebista's fall cannot exactly be determined,[93] but most historians write that he was assassinated in 44 BC.[88][85][95][86] Strabo narrates that after Burebista's death his empire fall apart and four (later five) smaller polities developed in its ruins.[93] The names of some of their kings were recorded by Roman writers.[96] For instance, Dicomes, "the king of the Getae, promised to come and join" Mark Antony "with a great army",[97] according to Plutarch.[98]

A new empire dominated by the Dacians emerged in the reign of

Bastarnae

Cassius Dio narrates that the Bastarnae "crossed the Ister and subdued the part of Moesia opposite them"[104] in 29 or 28 BC.[65] Marcus Licinius Crassus in short routed them.[65] In the first decades of the next century, the Sarmatians who arrived from the Pontic steppes became the dominant power of the regions up to that time inhabited by the Bastarnae.[105]

Roman provinces and the neighboring tribes

Lower Moesia

The year when the lands between the Lower Danube and the Black Sea, including the three Greek colonies of Callatis, Histria and Tomis, were annexed by the Roman Empire is uncertain. According to the historians Kurt W. Treptow and Marcel Popa, this happened in 46 AD.

The region flourished under

Dacia Trajana

The peaceful relationship between the Roman Empire and Decebalus's realm came to an end after Emperor

Under Emperor Trajan a procurator—a former consul—ruled the province.

Eutropius writes that Emperor Trajan transferred "vast numbers of people from all over the Roman world to inhabit the countryside and the cities", because "Dacia had, in fact, been depopulated"

The exploitation of natural resources—primarily mining of copper, gold, iron, lead, salt, and silver—had a preeminent role in the economy of Dacia province.[123][124] Archaeological research also revealed the existence of workshops producing pottery, weapons, glass for the local market.[125][126] Roads built for military purposes also contributed to the development of long-distance trade.[126]

Dacia became subject of frequent plundering raids by the Carpi and other neighboring tribes from the 230s.

Sarmatians

Costoboci

The Costoboci were a

During the Marcomannic War, the Costoboci plundered the Roman provinces in the Eastern Balkans as far as

Germanic tribes

The Marcomannic Wars, which lasted from 162 to 180, caused a series of population shifts along the eastern frontiers of the Roman Empire.

A new enemy of the Roman Empire, the

Carpi

The natives dwelling to the east of the Carpathians were collectively known as Carpi from the 3rd century.

Afterwards

References

- ^ Rotea 2005, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c Rotea 2005, p. 12.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Rotea 2005, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b c Georgescu 1991, p. 2.

- ^ a b Rotea 2005, p. 19.

- ^ Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 6.

- ^ a b Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 7.

- ^ Rotea 2005, p. 20.

- ^ a b Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 8.

- ^ Taylor 1994, p. 377.

- ^ a b c Taylor 1994, p. 378.

- ^ a b MacKendrick 1975, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d Georgescu 1991, p. 3.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 105.

- ^ a b MacKendrick 1975, p. 23.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 34.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 199.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 36.

- ^ a b MacKendrick 1975, p. 38.

- ^ a b Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 12.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 23, 38.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 42.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 25, 30.

- ^ Aristotle: The Politics (1305.a.37), p. 219.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 32.

- ^ a b MacKendrick 1975, pp. 23, 32.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 39.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 32, 39.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 33, 216.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 33–34, 216.

- ^ a b c d Oltean 2007, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 13.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 215.

- ^ Herodotus: The Histories (4.93), p. 266.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rustoiu 2005, p. 35.

- ^ Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Taylor 1994, p. 383.

- ^ Taylor 1994, pp. 399–400.

- ^ a b MacKendrick 1975, p. 48.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 27–29.

- ^ The History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides (2.8), p. 100.

- ^ a b Rustoiu 2005, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d Rustoiu 2005, p. 38.

- ^ The Anabasis by Arrian (1.4), p. 7.

- ^ Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 15.

- ^ a b Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 17.

- ^ a b Rustoiu 2005, p. 39.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 17.

- ^ Herodotus: The Histories (5.9), p. 306.

- ^ a b c Rustoiu 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Harding 1994, p. 334.

- ^ Herodotus: The Histories (4.48), p. 251.

- ^ Vékony 1994, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Herodotus: The Histories (4.104), p. 270.

- ^ a b c d Vékony 1994, p. 15.

- ^ Aristotle: Problems (19.28), p. 555.

- ^ a b Cunliffe 1994, p. 367.

- ^ a b Rustoiu 2005, p. 42.

- ^ a b Vékony 1994, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rustoiu 2005, p. 43.

- ^ Rustoiu 2005, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Cunliffe 1994, p. 362.

- ^ Livy: Rome and the Mediterranean (40.57.2), p. 481.

- ^ a b c d e f Rustoiu 2005, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Todd 2003, p. 23.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 145, 216.

- ^ a b c d MacKendrick 1975, p. 145.

- ^ Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 21.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 145–145.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, pp. 105, 199.

- ^ a b c d MacKendrick 1975, p. 146.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 147.

- ^ Ovid: Tristia (5.7.9-20), p. 45.

- ^ a b Oltean 2007, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Rustoiu 2005, p. 46.

- ^ a b Strabo (31 December 2012). "Mysia, Dacia, and the Danube". The Geography (Translated by Horace Leonard Jones) (7.3.13). http://penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Rustoiu 2005, p. 31.

- ^ Rustoiu 2005, p. 45.

- ^ Rustoiu 2005, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Oltean 2007, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Frontinus (20 October 2013). "On creating panic in the enemy's ranks". Stratagems (Translated by Charles E. Bennett) (2.4.3). http://penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Florus (29 October 2003). "The War with the Allobroges". Epitome of Roman History (Translated by E. S. Forster) (1.39.6). http://penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 22.

- ^ a b Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 55.

- ^ a b Rustoiu 2005, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d MacKendrick 1975, p. 216.

- ^ Rustoiu 2005, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Strabo (31 December 2012). "Mysia, Dacia, and the Danube". The Geography (Translated by Horace Leonard Jones) (7.3.11). http://penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Taylor 1994, p. 404.

- ^ Oltean 2007, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rustoiu 2005, p. 49.

- ^ The Gothic History of Jordanes (11:71), p. 71.

- ^ Taylor 1994, p. 407.

- ^ Oltean 2007, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Plutarch (10 November 2012). "Antony". Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans (Translated by John Dryden). ebooks.adelaide.edu.au. Archived from the original on August 10, 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ Oltean 2007, p. 49.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e Vékony 1994, p. 27.

- ^ a b Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 23.

- ^ Cassius Dio (16 April 2011). "The reign and character of Domitian, notoriously paranoid and cruel". Roman History (Translated by Earnest Cary) (67.7.4). penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Cassius Dio (16 April 2011). "Antony and Cleopatra. Suicide of Antony. Octavian conquers Egypt. Octavian celebrates triumphs in Rome. Marcus Crassus conquers Moesia". Roman History (Translated by Earnest Cary) (51.23.2). penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ a b Heather 2010, p. 114.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. xiv.

- ^ a b c Opreanu 2005, p. 110.

- ^ a b MacKendrick 1975, p. 217.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, p. 61.

- ^ a b MacKendrick 1975, p. 218.

- ^ a b Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 25.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, p. 6.

- ^ Oltean 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, p. 67.

- ^ Oltean 2007, p. 56.

- ^ a b Oltean 2007, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d Opreanu 2005, p. 70.

- ^ Eutropius: Breviarium (8.6.2.), p. 50.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, p. 299.

- ^ Vékony 1994, p. 44.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, pp. 74, 76.

- ^ Vékony 1994, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Vékony 1994, p. 37.

- ^ a b Opreanu 2005, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Vékony 1994, p. 52.

- ^ Eutropius: Breviarium (9.8.2.), p. 57.

- ^ a b Opreanu 2005, p. 102.

- ^ "The Life of Aurelian". Historia Augusta (Translated by David Magie) (39.7.). http://penelope.uchicago.edu. 11 June 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Bolovan et al. 1997, p. 42.

- ^ Opreanu 2005, p. 104.

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 78.

- ^ Cassius Dio (16 April 2011). "Wars against the Marcomans and the Iazyges. The revolt of Cassius in Syria ends in Cassius' death. Character of Marcus Aurelius". Roman History (Translated by Earnest Cary) (72.12.1). penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Rustoiu 2005, p. 99.

- ^ a b Bichir 1976, p. 161.

- ^ a b Rustoiu 2005, p. 98.

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 97.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 153.

- ^ Todd 2003, p. 55.

- ^ a b Opreanu 2005, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Opreanu 2005, p. 99.

- ^ a b Heather 2010, p. 109.

- ^ Wolfram 1988, p. 42.

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 127.

- ^ The Gothic History of Jordanes (16:91), p. 77.

- ^ Wolfram 1988, p. 45.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 65.

- ^ Bichir 1976, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Wolfram 1988, p. 44, 396.

Sources

Primary sources

- Aristotle: Problems, Books 1–19 (Edited and Translated by Robert Mayhew) (2011). President and Fellows of Harvard College. ISBN 978-0-674-99655-7.

- Eutropius: Breviarium (Translated with and introduction and commentary by H. W. Bird) (1993). Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-208-3.

- Herodotus: The Histories (A new translation by Robin Waterfield) (1998). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953566-8.

- Livy: Rome and the Mediterranean (Translated by Henry Bettenson with an Introduction by A. H. McDonald) (1976). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044318-5.

- "Ovid: Tristia" In Ovid: The Poems of Exile – Tristia and the Black Sea Letters (Translated with an Introduction by Peter Green) (2005), pp. 1–106. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24260-2.

- "The Anabasis by Arrian". In Arrian: Alexander the Great – The Anabasis and the Indica (A new translation by Martin Hammond) (2013), pp. 1–225. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958724-7.

- The Gothic History of Jordanes (in English Version with an Introduction and a Commentary by Charles Christopher Mierow, Ph.D., Instructor in Classics in Princeton University) (2006). Evolution Publishing. ISBN 1-889758-77-9.

- ISBN 978-1-466-430396.

- The Politics of Aristotle (Translated, with Introduction, Analysis and Notes by Peter L. Phillips Simpson) (1997). The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2327-9.

Secondary sources

- Bichir, Gh. (1976). The Archaeology and History of the Carpi from the Second to the Fourth Century AD (BAR Supllementary Series 16(i)). Gh. Bichir and Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România. ISBN 0-904531-55-4.

- Bolovan, Ioan; Constantiniu, Florin; Michelson, Paul E.; Pop, Ioan Aurel; Popa, Cristian; Popa, Marcel; Scurtu, Ioan; Treptow, Kurt W.; Vultur, Marcela; Watts, Larry L. (1997). A History of Romania. The Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 973-98091-0-3.

- Cunliffe, Barry (1994). "Iron Age Societies in Western Europe and Beyond, 800–140 BC". In Cunliffe, Barry (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 336–372. ISBN 978-0-19-285441-4.

- Georgescu, Vlad (1991). The Romanians: A History. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0511-9.

- Harding, Anthony (1994). "Reformation in Barbarian Europe, 1300–600 BC". In Cunliffe, Barry (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 304–335. ISBN 978-0-19-285441-4.

- Heather, Peter (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973560-0.

- MacKendrick, Paul (1975). The Dacian Stones Speak. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1226-9.

- Oltean, Ioana A. (2007). Dacia: Landscape, Colonisation and Romanization. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41252-0.

- Opreanu, Coriolan Horaţiu (2005). "The North-Danube Regions from the Roman Province of Dacia to the Emergence of the Romanian Language (2nd–8th Centuries AD)". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (eds.). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 59–132. ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.

- Rotea, Mihai (2005). "Prehistory". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (eds.). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 9–29. ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.

- Rustoiu, Aurel (2005). "Dacia before the Romans". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (eds.). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 31–58. ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.

- Taylor, Timothy (1994). "Thracians, Scythians, and Dacians, 800 BC–AD 300". In Cunliffe, Barry (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 373–410. ISBN 978-0-19-285441-4.

- Todd, Malcolm (2003). The Early Germans. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-631-16397-2.

- Treptow, Kurt W.; Popa, Marcel (1996). Historical Dictionary of Romania (European Historical Dictionaries, No. 16.). The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-3179-1.

- Vékony, Gábor (1994). "The Prehistory of Dacia". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 3–16. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.

- Wolfram, Herwig (1988). History of the Goths (Translated by Thomas J. Dunlap; New and completely revised from the second German edition). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06983-1.