Corticosteroid

| Corticosteroid | ||

|---|---|---|

Chemical class Steroids | | |

| Legal status | ||

| In Wikidata | ||

Corticosteroids are a class of

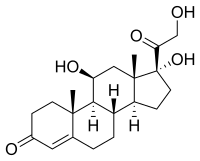

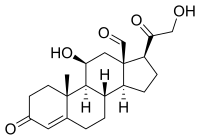

Some common naturally occurring steroid hormones are

Classes

- Glucocorticoids such as cortisol affect carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism, and have anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, anti-proliferative, and vasoconstrictive effects.[2] Anti-inflammatory effects are mediated by blocking the action of inflammatory mediators (transrepression) and inducing anti-inflammatory mediators (transactivation).[2] Immunosuppressive effects are mediated by suppressing delayed hypersensitivity reactions by direct action on T-lymphocytes.[2] Anti-proliferative effects are mediated by inhibition of DNA synthesis and epidermal cell turnover.[2] Vasoconstrictive effects are mediated by inhibiting the action of inflammatory mediators such as histamine.[2]

- electrolyte and water balance by modulating ion transport in the epithelial cells of the renal tubules of the kidney.[2]

Medical uses

Synthetic

Medical conditions treated with systemic corticosteroids:[2][4]

- Allergy and respirology medicine

- Asthma (severe exacerbations)

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Allergic rhinitis

- Atopic dermatitis

- Hives

- Angioedema

- Anaphylaxis

- Food allergies

- Drug allergies

- Nasal polyps

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- Sarcoidosis

- Eosinophilic pneumonia

- Some other types of pneumonia (in addition to the traditional antibiotic treatment protocols)

- Interstitial lung disease

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology (usually at physiologic doses)

- Gastroenterology

- Hematology

- Lymphoma

- Leukemia

- Hemolytic anemia

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Multiple Myeloma

- Rheumatology/Immunology

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Polymyalgia rheumatica

- Polymyositis

- Dermatomyositis

- Polyarteritis

- Vasculitis

- Ophthalmology

- Other conditions

- Multiple sclerosis relapses

- Organ transplantation

- Nephrotic syndrome

- flare ups)

- Cerebral edema

- IgG4-related disease

- Prostate cancer

- Tendinosis

- Lichen planus

Topical formulations are also available for the

Typical

A variety of steroid medications, from anti-allergy nasal sprays (

Corticosteroids have been widely used in treating people with traumatic brain injury.[8] A systematic review identified 20 randomised controlled trials and included 12,303 participants, then compared patients who received corticosteroids with patients who received no treatment. The authors recommended people with traumatic head injury should not be routinely treated with corticosteroids.[9]

Pharmacology

Corticosteroids act as agonists of the glucocorticoid receptor and/or the mineralocorticoid receptor.

In addition to their corticosteroid activity, some corticosteroids may have some progestogenic activity and may produce sex-related side effects.[10][11][12][13]

Pharmacogenetics

Asthma

Patients' response to inhaled corticosteroids has some basis in genetic variations. Two genes of interest are CHRH1 (corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1) and TBX21 (transcription factor T-bet). Both genes display some degree of polymorphic variation in humans, which may explain how some patients respond better to inhaled corticosteroid therapy than others.[14][15] However, not all asthma patients respond to corticosteroids and large sub groups of asthma patients are corticosteroid resistant.[16]

A study funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute of children and teens with mild persistent asthma found that using the control inhaler as needed worked the same as daily use in improving asthma control, number of asthma flares, how well the lungs work, and quality of life. Children and teens using the inhaler as needed used about one-fourth the amount of corticosteroid medicine as children and teens using it daily.[17][18]

Adverse effects

Use of corticosteroids has numerous side-effects, some of which may be severe:

- Severe amoebic colitis: Fulminant amoebic colitis is associated with high case fatality and can occur in patients infected with the parasite Entamoeba histolytica after exposure to corticosteroid medications.[19]

- Neuropsychiatric: anxiety,[21] depression. Therapeutic doses may cause a feeling of artificial well-being ("steroid euphoria").[22] The neuropsychiatric effects are partly mediated by sensitization of the body to the actions of adrenaline. Therapeutically, the bulk of corticosteroid dose is given in the morning to mimic the body's diurnal rhythm; if given at night, the feeling of being energized will interfere with sleep. An extensive review is provided by Flores and Gumina.[23]

- Cardiovascular: Corticosteroids can cause sodium retention through a direct action on the kidney, in a manner analogous to the mineralocorticoid aldosterone. This can result in fluid retention and hypertension.

- Metabolic: Corticosteroids cause a movement of body fat to the face and torso, resulting in "moon face", "buffalo hump", and "pot belly" or "beer belly", and cause movement of body fat away from the limbs. This has been termed corticosteroid-induced lipodystrophy. Due to the diversion of amino-acids to glucose, they are considered anti-anabolic, and long term therapy can cause muscle wasting (muscle atrophy).[24] Besides muscle atrophy, steroid myopathy includes muscle pains (myalgias), muscle weakness (typically of the proximal muscles), serum creatine kinase normal, EMG myopathic, and some have type II (fast-twitch/glycolytic) fibre atrophy.[25]

- Endocrine: By increasing the production of glucose from amino-acid breakdown and opposing the action of insulin, corticosteroids can cause diabetes mellitus.[27]

- Skeletal: Steroid-induced osteoporosis may be a side-effect of long-term corticosteroid use.[28][29][30] Use of inhaled corticosteroids among children with asthma may result in decreased height.[31]

- Gastro-intestinal: While cases of

- Eyes: chronic use may predispose to cataract and glaucoma. Clinical and experimental evidence indicates that corticosteroids can cause permanent eye damage by inducing central serous retinopathy (CSR, also known as central serous chorioretinopathy, CSC).[34] This should be borne in mind when treating patients with optic neuritis. There is experimental and clinical evidence that, at least in optic neuritis speed of treatment initiation is important.[35]

- Vulnerability to infection: By suppressing immune reactions (which is one of the main reasons for their use in allergies), steroids may cause infections to flare up, notably candidiasis.[36]

- Pregnancy: Corticosteroids have a low but significant contraindicated in pregnancy.[37]

- Habituation: Topical steroid addiction (TSA) or red burning skin has been reported in long-term users of topical steroids (users who applied topical steroids to their skin over a period of weeks, months, or years).[38][39] TSA is characterised by uncontrollable, spreading dermatitis and worsening skin inflammation which requires a stronger topical steroid to get the same result as the first prescription. When topical steroid medication is lost, the skin experiences redness, burning, itching, hot skin, swelling, and/or oozing for a length of time. This is also called 'red skin syndrome' or 'topical steroid withdrawal' (TSW). After the withdrawal period is over the atopic dermatitis can cease or is less severe than it was before.[40]

- In children the short term use of steroids by mouth increases the risk of vomiting, behavioral changes, and sleeping problems.[41]

Biosynthesis

The corticosteroids are synthesized from

Classification of corticosteroids

By chemical structure

In general, corticosteroids are grouped into four classes, based on chemical structure. Allergic reactions to one member of a class typically indicate an intolerance of all members of the class. This is known as the "Coopman classification".[42][43]

The highlighted steroids are often used in the screening of allergies to topical steroids.[44]

Group A – Hydrocortisone type

Hydrocortisone, hydrocortisone acetate, cortisone acetate, tixocortol pivalate, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and prednisone.

Amcinonide, budesonide, desonide, fluocinolone acetonide, fluocinonide, halcinonide, triamcinolone acetonide, and Deflazacort (O-isopropylidene derivative)

Group C – Betamethasone type

Beclometasone, betamethasone, dexamethasone, fluocortolone, halometasone, and mometasone.

Group D – Esters

Group D1 – Halogenated (less labile)

Group D2 – Labile prodrug esters

Ciclesonide, cortisone acetate, hydrocortisone aceponate, hydrocortisone acetate, hydrocortisone buteprate, hydrocortisone butyrate, hydrocortisone valerate, prednicarbate, and tixocortol pivalate.

By route of administration

Topical steroids

For use topically on the skin, eye, and mucous membranes.

Topical corticosteroids are divided in potency classes I to IV in most countries (A to D in Japan). Seven categories are used in the United States to determine the level of potency of any given topical corticosteroid.

Inhaled steroids

For nasal mucosa, sinuses, bronchi, and lungs.[45]

This group includes:

- Flunisolide[46]

- Fluticasone furoate[46]

- Fluticasone propionate[46]

- Triamcinolone acetonide[46]

- Beclomethasone dipropionate[46]

- Budesonide[46]

- Mometasone furoate

- Ciclesonide

There also exist certain combination preparations such as

Oral forms

Such as prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, or dexamethasone.[47]

Systemic forms

Available in injectables for intravenous and parenteral routes.[47]

History

| Corticosteroid | Introduced |

|---|---|

| Cortisone | 1948 |

| Hydrocortisone | 1951 |

Fludrocortisone acetate |

1954[51] |

| Prednisolone | 1955 |

| Prednisone | 1955[52] |

| Methylprednisolone | 1956 |

| Triamcinolone | 1956 |

| Dexamethasone | 1958 |

| Betamethasone | 1958 |

| Triamcinolone acetonide | 1958 |

| Fluorometholone | 1959 |

| Deflazacort | 1969[53] |

Tadeusz Reichstein, Edward Calvin Kendall, and Philip Showalter Hench were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine in 1950 for their work on hormones of the adrenal cortex, which culminated in the isolation of cortisone.[54]

Initially hailed as a

In 1952, D.H. Peterson and H.C. Murray of

Etymology

The cortico- part of the name refers to the adrenal cortex, which makes these steroid hormones. Thus a corticosteroid is a "cortex steroid".

See also

- List of corticosteroids

- List of corticosteroid cyclic ketals

- List of corticosteroid esters

- List of steroid abbreviations

References

- ^ a b c Nussey S, Whitehead S (2001). "The adrenal gland". Endocrinology: An Integrated Approach. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers.

- ^ PMID 23947590.

- S2CID 252663155.

- PMID 27469590.

- ^ Werner R (2005). A massage therapist's guide to Pathology (3rd ed.). Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- PMID 12359603.

- ^ "The New York Times :: A Breathing Technique Offers Help for People With Asthma". buteykola.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- ^ Alderson P, Roberts I. "Plain Language Summary". Corticosteroids for acute traumatic brain injury. The Cochrane Collaboration. p. 2.

- PMID 15674869.

- PMID 10518812.

- PMID 27874912.

- PMID 7121132.

- PMID 376542.

- PMID 15128701.

- PMID 15604153.

- PMID 29524537.

- S2CID 199380330.

- ^ "Managing Mild Asthma in Children Age Six and Older". Managing Mild Asthma in Children Age Six and Older | PCORI. 2021-08-13. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- PMID 27467600.

- ^ Hall R. "Psychiatric Adverse Drug Reactions: Steroid Psychosis". Director of Research Monarch Health Corporation Marblehead, Massachusetts. Archived from the original on 2013-07-17. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- S2CID 8904351.

- PMID 3242575.

- ^ Benjamin H. Flores and Heather Kenna Gumina. The Neuropsychiatric Sequelae of Steroid Treatment. URL:http://www.dianafoundation.com/articles/df_04_article_01_steroids_pg01.html

- PMID 20473154.

- PMID 33305169.

- PMID 16901792.

- PMID 12220369.

- S2CID 224822416.

- S2CID 221078530.

- S2CID 232771681.

- PMID 25030198.

- S2CID 13594804.

- S2CID 5140517.

- PMID 26586979.

- PMID 31740484.

- PMID 12839324.

- PMID 11948561.

- . Retrieved 2014-12-18.

- PMID 22837556.

- PMID 25378953.

- PMID 26768830.

- ISBN 978-1-55009-378-0.

- S2CID 40425526.

- ^ Wolverton SE (2001). Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. WB Saunders. p. 562.

- ^ "Asthma Steroids: Inhaled Steroids, Side Effects, Benefits, and More". Webmd.com. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mayo Clinic Staff (September 2015). "Asthma Medications: Know your options". MayoClinic.org. Retrieved 2018-02-27.

- ^ a b "Systemic steroids (corticosteroids). DermNet NZ". . DermNet NZ. 2012-05-19. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- PMID 16178782.

- PMID 13875857.

- ISBN 978-1-60805-234-9.

- ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3.

- ISBN 978-94-024-0844-7.

- PMID 19882026.

- PMID 24540604. Archived from the original(PDF) on 15 April 2017.

- S2CID 16777111.

- ^ "Contact Allergen of the Year: Corticosteroids: Introduction". Medscape.com. 2005-06-13. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- ^ US 2462133, Sarett LH, "Process of Treating Pregnene Compounds", issued 1947

- PMID 20262743.

- .

- ^ US 2752339, Julian L, Cole JW, Meyer EW, Karpel WJ, "Preparation of Cortisone", issued 1956