Tacrolimus

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Prograf, Advagraf, Protopic, others |

| Other names | FK-506, fujimycin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601117 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

Topical, by mouth, intravenous | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 24% (5–67%), less after eating food rich in fat |

| Protein binding | ≥98.8% |

| Metabolism | Liver CYP3A4, CYP3A5 |

| Elimination half-life | 11.3 h for transplant patients (range 3.5–40.6 h) |

| Excretion | Mostly fecal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Tacrolimus, sold under the brand name Prograf among others, is an

Tacrolimus inhibits

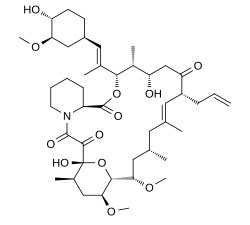

Chemically, it is a

Medical uses

Organ transplantation

It has similar immunosuppressive properties to

Skin

As an

It is applied on the active lesions until they heal off, but may also be used continuously in low doses (twice a week), and applied to the thinner skin over the face and eyelids.[citation needed] Clinical trials of up to one year have been conducted. Recently it has also been used to treat segmental vitiligo in children, especially in areas on the face.[20]

Eyes

Tacrolimus solution, as drops, is sometimes prescribed by veterinarians for

Contraindications and precautions

Contraindications and precautions include:[24]

- Hepaticdisease

- Immunosuppression

- Infants

- Infection

- Neoplasticdisease, such as:

- Oliguria

- Pregnancy

- QT interval prolongation

- UV) exposure

- Grapefruit juice[25]

Topical use

- Occlusive dressing

- Known or suspected malignant lesions

- Netherton's syndromeor similar skin diseases

- Certain skin infections[19]

Side effects

By mouth or intravenous use

Side effects can be severe and include

In addition, it may potentially increase the severity of existing fungal or infectious conditions such as

Carcinogenesis and mutagenesis

In people receiving immunosuppressants to reduce transplant graft rejection, an increased risk of malignancy (cancer) is a recognised complication.

Topical use

The most common adverse events associated with the use of topical tacrolimus ointments, especially if used over a wide area, include a burning or itching sensation on the initial applications, with increased sensitivity to sunlight and heat on the affected areas.[

Cancer risks

Tacrolimus and a related drug for eczema (

Interactions

Also like cyclosporin, it has a wide range of interactions. Tacrolimus is primarily metabolised by the cytochrome P450 system of liver enzymes, and there are many substances that interact with this system and induce or inhibit the system's metabolic activity.[24]

Interactions include that with grapefruit which increases tacrolimus plasma concentrations. As infections are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the post-transplant patient, the most commonly[citation needed] reported interactions include interactions with anti-microbial drugs. Macrolide antibiotics including erythromycin and clarithromycin, as well as several of the newer classes of antifungals, especially of the azole class (fluconazole, voriconazole), increase tacrolimus levels by competing for cytochrome enzymes.[24]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

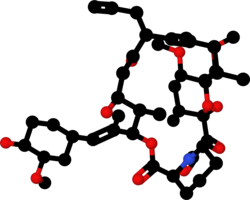

Tacrolimus is a

In detail, tacrolimus reduces

Pharmacokinetics

Oral tacrolimus is slowly absorbed in the

The substance is metabolized in the liver, mainly via CYP3A, and in the intestinal wall. All metabolites found in the circulation are inactive. Biological half-life varies widely and seems to be higher for healthy persons (43 hours on average) than for patients with liver transplants (12 hours) or kidney transplants (16 hours), due to differences in clearance. Tacrolimus is predominantly eliminated via the faeces in form of its metabolites.[24][36]

When applied locally on eczema, tacrolimus has little to no bioavailability.[24]

Pharmacogenetics

The predominant enzyme responsible for metabolism of tacrolimus is

Studies have shown that genetic polymorphisms of genes other than CYP3A5, such as NR1I2[42][43] (encoding PXR), also significantly influence the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus.

History

Tacrolimus was discovered in 1987; it was among the first macrolide immunosuppressants discovered, preceded by the discovery of

The early development (investigational new drug phase) of tacrolimus, called at the time by the development code FK-506, happened in the next several years. A firsthand account of that process is given in Thomas Starzl's 1992 memoir.[47]

Tacrolimus was first

Tacrolimus was approved for medical use in the European Union in 2002, for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.[52] In 2007, the indications were expanded to include the prophylaxis of transplant rejection in adult kidney or liver allograft recipients and the treatment of allograft rejection resistant to treatment with other immunosuppressive medicinal products in adults.[53] In 2009, the indications were expanded to include the prophylaxis of transplant rejection in adult and paediatric, kidney, liver or heart allograft recipients and the treatment of allograft rejection resistant to treatment with other immunosuppressive medicinal products in adults and children.[54]

Available forms

A branded version of the drug is owned by Astellas Pharma, and is sold under the brand name Prograf, given twice daily. A number of other manufacturers hold marketing authorisation for alternative brands of the twice-daily formulation.[55]

Once-daily formulations with marketing authorisation include Advagraf (Astellas Pharma) and Envarsus (marketed as Envarsus XR in US by

The topical formulation is marketed by

Biosynthesis

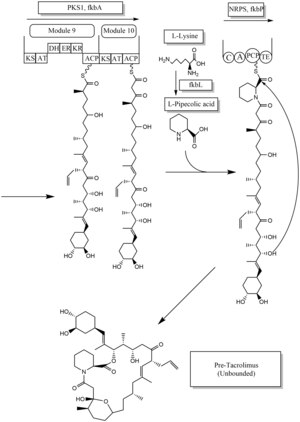

The biosynthesis of tacrolimus is hybrid synthesis of both type 1

There are several possible ways of biosynthesis of tacrolimus. The fundamental units for biosynthesis are following: one molecule of 4,5-dihydroxycyclohex-1-enecarboxylic acid (DHCHC) as a starter unit, four molecules of malonyl-CoA, five molecules of methylmalonyl-CoA, one molecule of allylmalonyl-CoA as elongation units. However, two molecules of malonyl-CoA are able to be replaced by two molecules of methoxymalonyl CoA. Once two malonyl-CoA molecules are replaced, post-synthase tailoring steps are no longer required where two methoxymalonyl CoA molecules are substituted. The biosynthesis of methoxymalonyl CoA to Acyl Carrier protein is proceeded by five enzymes (fkbG, fkbH, fkbI, fkbJ, and fkbK). Allylmalonyl-CoA is also able to be replaced by propionylmalonyl-CoA.[56]

The starter unit, DHCHC from the chorismic acid is formed by fkbO enzyme and loaded onto CoA-ligase domain (CoL). Then, it proceeds to NADPH dependent reduction(ER). Three enzymes, fkbA,B,C enforce processes from the loading module to the module 10, the last step of PKS 1. fkbB enzyme is responsible of allylmalonyl-CoA synthesis or possibly propionylmalonyl-CoA at C21, which it is an unusual step of general PKS 1. As mentioned, if two methoxymalonyl CoA molecules are substituted for two malonyl-CoA molecules, they will take place in module 7 and 8 (C13 and C15), and fkbA enzyme will enforce this process. After the last step (module 10) of PKS 1, one molecule of L-pipecolic acid formed from L-lysine and catalyzed through fkbL enzyme synthesizes with the molecule from the module 10. The process of L-pipecolic acid synthesis is NRPS enforced by fkbP enzyme. After synthesizing the entire subunits, the molecule is cyclized. After the cyclization, the pre-tacrolimus molecule goes through the post-synthase tailoring steps such as oxidation and S-adenosyl methionine. Particularly fkbM enzyme is responsible of alcohol methylation targeting the alcohol of DHCHC starter unit (Carbon number 31 depicted in brown), and fkbD enzyme is responsible of C9 (depicted in green). After these tailoring steps, the tacrolimus molecule becomes biologically active.[56][57][58]

Research

Lupus nephritis

Tacrolimus has been shown to reduce the risk of serious infections while also increasing remission of kidney function in lupus nephritis.[59][60]

Ulcerative colitis

Tacrolimus has been used to suppress the inflammation associated with ulcerative colitis (UC), a form of inflammatory bowel disease. Although almost exclusively used in trial cases only, tacrolimus has shown to be significantly effective in the suppression of flares of UC.[61] A 2022 updated Cochrane systematic review found that tacrolimus may be superior to placebo in achieving remission and improvement in UC.[62]

References

- ^ "Tacrolimus Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 3 October 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Drug and medical device highlights 2019: Helping you maintain and improve your health". Health Canada. 18 November 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ "Prograf- tacrolimus capsule, gelatin coated Prograf- tacrolimus injection, solution Prograf- tacrolimus granule, for suspension". DailyMed. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Advagraf EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Protopic EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- PMID 16008701.

- ^ "Tacrolimus for Dogs and Cats".

- PMID 21436963.

- hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Tacrolimus - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ a b McCauley J (19 May 2004). "Long-Term Graft Survival In Kidney Transplant Recipients". Slide Set Series on Analyses of Immunosuppressive Therapies. Medscape. Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- PMID 17054241.

- S2CID 10417106.

- S2CID 23530214.

- PMID 26132597.

- ^ S2CID 253470127.

- ^ a b Haberfeld, H, ed. (2015). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. Protopic.

- PMID 15523355.

- ^ "Tacrolimus, Ophthalmic" (PDF). Plumbs Veterinary Medication Guides. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ Naves FE, Sakassegawa E (10 May 2013). "Treatment of Dry Eye Using 0.03% Tacrolimus Eye Drops". U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- PMID 33522964.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Haberfeld, H, ed. (2015). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. Prograf.

- PMID 16702731.

- PMID 19218475.

- S2CID 39537409.

- PMID 17484951.

- ^ "Key Statistics for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- PMID 16021174.

- ^ Cox NH, Smith CH (December 2002). "Advice to dermatologists re topical tacrolimus" (PDF). Therapy Guidelines Committee. British Association of Dermatologists. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2013.

- S2CID 253470127.

- ISBN 978-0-07-144040-0.

- S2CID 22094672.

- PMID 16213293.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- ^ Bains RK. "Molecular diversity and population structure at the CYP3A5 gene in Africa" (PDF). University College London. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- S2CID 33877550.

- S2CID 28346861.

- S2CID 27047235.

- PMID 23922006.

- S2CID 19900291.

- PMID 27958377.

- PMID 2445721.

- PMID 15896681. Supports source organism, but not team information

- ^ Ponner, B, Cvach, B (Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co.): Protopic Update 2005

- ISBN 978-0-8229-3714-2.

- ^ "Prograf: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Prograf: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Tacrolimus (Systemic) Monograph. Accessed 16 December 2021.

- ^ "Tacrolimus: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Protopic EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Advagraf EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Modigraf EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Joint Formulary Committee. "British National Formulary (online)". London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ PMID 29724001.

- PMID 23435975.

- S2CID 32967249.

- PMID 27623861.

- PMID 27619512.

- S2CID 10233231.

- PMID 35388476.

Further reading

- Lv X, Qi J, Zhou M, Shi B, Cai C, Tang Y, et al. (June 2020). "Comparative efficacy of 20 graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis therapies for patients after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: A multiple-treatments network meta-analysis". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 150: 102944. S2CID 214794350.

External links

- "Tacrolimus Injection". MedlinePlus.

- "Tacrolimus Topical". MedlinePlus.

- Tacrolimus at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "FDA Approves New Use of Transplant Drug Based on Real-World Evidence". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 September 2021.