Takht-i Sangin

Takht-i Sangin (

Description

Takht-i Sangin is located on a raised flat area sandwiched between the west bank of the Amu Darya river and the base of the Teshik Tosh mountain to the west. This terrace is about three kilometres long from north to south and varies from 100 to 450 metres in width. The site is immediately south of the point where the Vakhsh / Amu Darya river (the ancient Oxus) is met by the Panj river (the ancient Ochus), about five kilometres north of

Temple of Oxus

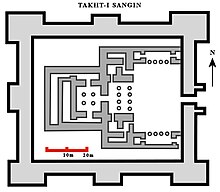

In the middle of the terrace, there was a citadel, measuring around 170-210 metres by 240 metres, on top of a ten-metre-high artificial mound. This mount was surrounded by a ditch and a two-metre-high stone wall on the northern, western, and southern sides. On the eastern side it bordered the river, and there are traces of a dock, which is now inaccessible.[7]

The centre of the citadel contained the Oxus Temple, which was first built around 300 BC.

The excavators,

Votive finds

Somewhere between 5,000 and 8,000 other votive offerings in gold, silver, bronze, iron, lead, glass, plaster, terracotta, precious stones, limestone, shell, bone, ivory, and wood have been found.[6] Most of these were located in the central hall of the temple and the corridors behind it, both above ground and in buried caches. These votives include portraits of Greco-Bactrian kings, jewellery, and furniture, but especially weapons and armour.[6] Many of these votives were probably buried when the community was sacked by the Kushans in the 130s BC.[6] After the sack, the rest of the site was abandoned, but the temple remained in use until the third century AD, with the Kushans continuing to dedicate weapons, especially arrowheads, in very large numbers.[6]

In the courtyard, excavators recovered a small stone base surmounted by a little bronze statuette of a Silenus, perhaps Marsyas, playing the aulos, with a Greek inscription reading "[in fulfilment of] a vow, Atrosokes dedicated [this] to Oxus." This is the basis for the identification of the whole sanctuary as a temple of Oxus.[4] Lindström calls the combination of Greek mythological figure, a man with an Iranian name, and a local Bactrian deity "a mixture of influences that is characteristic of ... the Hellenistic Far East."[10]

Takht-i Sangin is a suspected original location for the Oxus Treasure that now resides in the Victoria and Albert Museum and British Museum.[3][15]

Research history

Brief investigations of Takht-i Sangin were undertaken in 1928, 1950, and 1956.

This site was added to the

Artifacts

Achaemenid period (6th-4th century BC)

-

Votive plaque in cloisonné with man leading a camel, Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i Sangin, 6th-5th century BC

-

Akinakes holder, ivory, Takht-i Sangin, Temple of the Oxus, Tajikistan, 5th-4th century BC.[1]

Seleucid and Greco-Bactrian periods (4th-2nd century BC)

-

Alexander-Herakles head, Takht-i Sangin, Temple of the Oxus, 3rd century BCE.[25]

-

Head of a Seleucid or Greco-Bactrian ruler wearing a diadem, Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i-Sangin, 3rd-2nd century BC.[1]

-

Palmette design, Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i Sangin, 3rd-2nd century BC

-

Painted clay and alabaster head, Takht-i Sangin, Tajikistan, 3rd-2nd century BCE. Possibly a Zoroastrian priest or a Bactrian ruler (Satrap), Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i-Sangin, 3rd-2nd century BCE.[26][1]

-

Young man (Apollo or Eros type), Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i Sangin, 3rd-2nd century BC

-

Aquatic divinity, Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i-Sangin, first half of 2nd century BC.[1]

-

Decorated lid of a large pyxis, similar to those found in Ai-Khanoum, Takht-i Sangin, 3rd-2nd century BC, National Museum of Antiquities of Tajikistan (M 7126)

Saka (Scythian) period (2nd century BC - 2nd century AD)

Various artefacts are also dated the Saka (Scythian) period.

-

Fragment of the head of an elephant, ivory, Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i Sangin, 2nd-1st century BC[1]

-

Hunters ivory plaque, Takht-i Sangin, Temple of the Oxus, 1st century BC- 1st century AD. The design is comparable to the hunting scenes of the Orlat plaques.[27]

-

Right hunter detail, Takht-i Sangin, Temple of the Oxus, 1st century BC- 1st century AD

See also

Notes

- ^ JSTOR 24048765.

- ^ Wood, Rachel (2011). "Cultural convergence in Bactria: the votives from the Temple of the Oxus at Takht-i Sangin, in "From Pella to Gandhara"". In A. Kouremenos, S. Chandrasekaran & R. Rossi ed. 'From Pella to Gandhara: Hybridization and Identity in the Art and Architecture of the Hellenistic East'. Oxford: Archaeopress: 141–151.

- ^ a b Holt 1989, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lindström 2021, p. 291.

- ^ a b Lindström 2021, p. 288.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lindström 2021, p. 295.

- ^ a b c Lindström 2021, p. 289.

- JSTOR 24048765.

- JSTOR 24048765.

- ^ a b Lindström 2021, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Lindström 2021, p. 293.

- ^ a b Lindström 2021, p. 294.

- ^ Lindström 2021, p. 292.

- JSTOR 24049090.

- ^ a b The Site of Ancient Town of Takhti-Sangin - UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- ^ Litvinsky & Pitschikjan 2000.

- ^ Litvinsky 2001.

- ^ Litvinsky 2010.

- ^ Drujinina & Boroffka 2006.

- ^ Drujinina et al. 2009.

- ^ Druzhinina, Khudzhalgeldiyev & Inagaki 2010.

- ^ Druzhinina, Khudzhalgeldiyev & Inagaki 2011.

- ^ Gelin 2015.

- JSTOR 24048765.

- JSTOR 24048765.

- ^ "Colorado State University".

- ISBN 978-1-78969-407-9.

- ^ Francfort, Henri-Paul (2020). "Sur quelques vestiges et indices nouveaux de l'hellénisme dans les arts entre la Bactriane et le Gandhāra (130 av. J.-C.-100 apr. J.-C. environ)". Journal des Savants: 45, Fig.19.

(French) "Takht-i Sangin (Tadjikistan). Rondelle de bronze à personnage en costume scythe et protomes de chevaux."

References

- The Site of Ancient Town of Takhti-Sangin - UNESCO World Heritage Centre Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ISBN 90-04-08612-9.

- Lindström, Gunvor (2021). "Southern Tajikistan". In Mairs, Rachel (ed.). The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek world. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 291–295. ISBN 9781138090699.

Further reading

- Litvinskij, B. A.; Pičikjan, I. R. (2002). Taxt-i Sangīn der Oxus-Tempel : Grabungsbefund, Statigraphie und Architektur. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 9783805329286.

- Litvinsky, B. A.; Pitschikjan, L. T. (2000). Эллинистический храм Окса в Бактрии : Юзхный Таджикистан. Том I, Раскопки, архитектура, религиозная жизнь = the temple of Oxus In Bactria (South Tajikistan): Excavations, architecture, religious life. Moskva: Vostočnaâ literatura. ISBN 5-02-018114-5.

- Litvinsky, B. A. (2001). Храм Окса в Бактрии : Юзхный Таджикистан. Том 2, Бактрийское вооружение в древневосточном и греческом контексте = the temple of Oxus In Bactria (South Tajikistan): Bactrian arm and armour in the ancient Eastern and Greek context. Moskva: Vostočnaâ literatura. ISBN 5-02-018194-3.

- Litvinsky, B. A. (2010). Храм Окса в Бактрии (Южный Такжикистан). В 3 томах. Том 3. Искусство, художественное ремесло, музыкальные инструменты. Moskva: Vostočnaâ literatura. ISBN 978-5-02-036438-7.

- Drujinina, A. P.; Boroffka, N. R. (2006). "First Preliminary Report on the Excavations at Takht-i Sangin". Bulletin of the Miho Museum. 6: 57–69.

- Drujinina, A. P.; Inagaki, H.; Hudjageldiev, T.; Rott, F. (2009). "Excavations of Takht-i Sangin City, Territory of Oxus Temple, in 2006". Bulletin of the Miho Museum. 9: 59–85.

- Druzhinina, A. P.; Khudzhalgeldiyev, T. U.; Inagaki, H. (2010). "Report on the Excavations of the Oxus Temple in Takht-i Sangin Settlement Site in 2007". Bulletin of the Miho Museum. 10: 63–82.

- Druzhinina, A. P.; Khudzhalgeldiyev, T. U.; Inagaki, H. (2011). "The Results of the Archaeological Excavations at Takht-i Sangin in 2008". Bulletin of the Miho Museum. 11: 13–30.

- Gelin, Mathilde (2015). "Nouvelles recherches à Takht-i Sangin". ПРОБЛЕМЫ ИСТОРИИ, ФИЛОЛОГИИ, КУЛЬТУРЫ = Journal of historical philological and cultural studies. 47: 32–45.

- Худжагелдиев, Т.У. (2017). "Исследования на городище Тахти-Сангин в 2013, г.". АРТ. 39: 87–98.

![Akinakes holder, ivory, Takht-i Sangin, Temple of the Oxus, Tajikistan, 5th-4th century BC.[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Akinakes_sheath_NMAT_M7251.jpg/133px-Akinakes_sheath_NMAT_M7251.jpg)

![Herakles vanquishing Acheloos, Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i-Sangin, 4th century BC.[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0c/Sword_handle_Herakles_Acheloos_MNAT_M7249.jpg/133px-Sword_handle_Herakles_Acheloos_MNAT_M7249.jpg)

![Alexander-Herakles head, Takht-i Sangin, Temple of the Oxus, 3rd century BCE.[25]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/93/Alexander-Herakles_head%2C_Takht-i_Sangin%2C_Temple_of_the_Oxus%2C_3rd_century_BCE.jpg/150px-Alexander-Herakles_head%2C_Takht-i_Sangin%2C_Temple_of_the_Oxus%2C_3rd_century_BCE.jpg)

![Head of a Seleucid or Greco-Bactrian ruler wearing a diadem, Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i-Sangin, 3rd-2nd century BC.[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Head_of_a_Seleucid_or_Greco-Bactrian_ruler_wearing_a_diadem%2C_Temple_of_the_Oxus%2C_Takht-i-Sangin%2C_3rd-2nd_century_BCE.jpg/150px-Head_of_a_Seleucid_or_Greco-Bactrian_ruler_wearing_a_diadem%2C_Temple_of_the_Oxus%2C_Takht-i-Sangin%2C_3rd-2nd_century_BCE.jpg)

![Painted clay and alabaster head, Takht-i Sangin, Tajikistan, 3rd-2nd century BCE. Possibly a Zoroastrian priest or a Bactrian ruler (Satrap), Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i-Sangin, 3rd-2nd century BCE.[26][1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/Head_of_Bactrian_ruler_%28Satrap%29%2C_Temple_of_the_Oxus%2C_Takht-i-Sangin%2C_3rd-2nd_century_BC.jpg/153px-Head_of_Bactrian_ruler_%28Satrap%29%2C_Temple_of_the_Oxus%2C_Takht-i-Sangin%2C_3rd-2nd_century_BC.jpg)

![Aquatic divinity, Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i-Sangin, first half of 2nd century BC.[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/Aquatic_divinity%2C_Temple_of_the_Oxus%2C_Takht-i-Sangin%2C_first_half_of_2nd_century_BCE.jpg/200px-Aquatic_divinity%2C_Temple_of_the_Oxus%2C_Takht-i-Sangin%2C_first_half_of_2nd_century_BCE.jpg)

![Fragment of the head of an elephant, ivory, Temple of the Oxus, Takht-i Sangin, 2nd-1st century BC[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/95/Fragment_of_the_head_of_an_elephant%2C_ivory%2C_Temple_of_the_Oxus%2C_Takht-i_Sangin%2C_2nd-1st_century_BCE.jpg/170px-Fragment_of_the_head_of_an_elephant%2C_ivory%2C_Temple_of_the_Oxus%2C_Takht-i_Sangin%2C_2nd-1st_century_BCE.jpg)

![Hunters ivory plaque, Takht-i Sangin, Temple of the Oxus, 1st century BC- 1st century AD. The design is comparable to the hunting scenes of the Orlat plaques.[27]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/18/Plaque_hunting_scenes_NMAT_M7118_n01.jpg/200px-Plaque_hunting_scenes_NMAT_M7118_n01.jpg)

![Medallion with man in Central Asian costume attending two horses, Takht-i Sangin, 2nd century BC-2nd century AD. The costume is said to be "Scythian".[28]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6a/Medal_groom_horses_NMAT_M7234.jpg/200px-Medal_groom_horses_NMAT_M7234.jpg)