Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Clockwise from top: Brihadisvara Temple | ||

|

Anthem: "Tamil Thai Valthu " (Invocation to Mother Tamil) | ||

Formation | 1 November 1956 | |

State Legislature | Unicameral | |

| • Assembly | Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly (234 seats) | |

| National Parliament | Parliament of India | |

| • Rajya Sabha | 18 seats | |

| • Lok Sabha | 39 seats | |

| High Court | Madras High Court | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 130,058 km2 (50,216 sq mi) | |

| • Rank | ||

Nilgiri Tahr | ||

| Tree | Asian Palm | |

| State highway mark | ||

| ||

| State highway of Tamil Nadu TN SH1 - TN SH223 | ||

| List of Indian state symbols | ||

Tamil Nadu (

Located on the south-eastern coast of the

.As the most urbanised state of India, Tamil Nadu boasts an

Etymology

The name is derived from Tamil language with nadu meaning "land" and Tamil Nadu meaning "the land of Tamils". The origin and precise etymology of the word Tamil is unclear with multiple theories attested to it.[5]

History

Prehistory (before 5th century BCE)

Sangam period (5th century BCE–3rd century CE)

The

The kingdoms had significant diplomatic and trade contacts with other kingdoms to the north and

Medieval era (4th–13th century CE)

Around the 7th century CE, the Kalabhras were overthrown by the Pandyas and Cholas, who patronised Buddhism and Jainism before the revival of

The Cholas became the dominant kingdom in the 9th century under

The Pandyas again reigned supreme early in the 13th century under

Vijayanagar and Nayak period (14th–17th century CE)

In the 13th and 14th century, there were repeated attacks from

Later conflicts and European colonization (17th to 20th century CE)

In the 18th century, the

Europeans started to establish trade centers from the 16th century along the eastern coast. The

By the 18th century, the British had conquered most of the region and established the

Failure of the summer monsoons and administrative shortcomings of the

Post-Independence (1947–present)

After the

Environment

Geography

Tamil Nadu covers an area of 130,058 km2 (50,216 sq mi) and is the tenth-largest state in India.

The Western Ghats runs south along the western boundary with the highest peak at

The

Tamil Nadu has a 1,076 km (669 mi)

Geology

Tamil Nadu falls mostly in a region of low seismic hazard with the exception of the western border areas that lie in a low to moderate hazard zone; as per the 2002 Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) map, Tamil Nadu falls in Zones II and III.

Climate

The region has a

The

Flora and fauna

Forests occupy an area of 22,643 km2 (8,743 sq mi) constituting 17.4% of the geographic area.

Important ecological regions of Tamil Nadu are the

Protected areas cover an area of 3,305 km2 (1,276 sq mi), constituting 2.54% of the geographic area and 15% of the 22,643 km2 (8,743 sq mi) recorded forest area of the state.

There is one conservation reserve at

| Animal | Bird | Butterfly | Tree | Fruit | Flower |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nilgiri tahr (Nilgiritragus hylocrius) | Emerald dove (Chalcophaps indica) | Tamil Yeoman (Cirrochroa thais) | Palmyra palm (Borassus flabellifer) | Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) | Glory lily (Gloriosa superba) |

Administration and politics

Administration

| Title | Name |

|---|---|

Governor

|

R. N. Ravi[145] |

Chief minister

|

M. K. Stalin[146] |

Chief Justice

|

S. V. Gangapurwala[147] |

Chennai is the capital of the state and houses the

Legislature

In accordance with the

Law and order

The

Politics

Elections in India are conducted by the

The Anti-Hindi agitations of Tamil Nadu led to the rise of Dravidian parties that formed Tamil Nadu's first government, in 1967.[179] In 1972, a split in the DMK resulted in the formation of the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) led by M. G. Ramachandran.[180] Dravidian parties continue to dominate Tamil Nadu electoral politics with the national parties usually aligning as junior partners to the major Dravidian parties, AIADMK and DMK.[181] M. Karunanidhi became the leader of the DMK after Annadurai and J. Jayalalithaa succeeded as the leader of AIADMK after M. G. Ramachandran.[182][176] Karunanidhi and Jayalalithaa dominated the state politics from the 1980s to early 2010s, serving as chief ministers combined for over 32 years.[176]

C. Rajagopalachari, the first Indian Governor General of India post independence, was from Tamil Nadu. The state has produced three Indian presidents, namely,

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 19,252,630 | — |

| 1911 | 20,902,616 | +8.6% |

| 1921 | 21,628,518 | +3.5% |

| 1931 | 23,472,099 | +8.5% |

| 1941 | 26,267,507 | +11.9% |

| 1951 | 30,119,047 | +14.7% |

| 1961 | 33,686,953 | +11.8% |

| 1971 | 41,199,168 | +22.3% |

| 1981 | 48,408,077 | +17.5% |

| 1991 | 55,858,946 | +15.4% |

| 2001 | 62,405,679 | +11.7% |

| 2011 | 72,147,030 | +15.6% |

| Source:Census of India[186] | ||

As per the

As of 2017[update], the state had the

Cities and towns

The capital of Chennai is the most populous urban agglomeration in the state with more than 8.6 million residents, followed by Coimbatore, Madurai, Tiruchirappalli and Tiruppur, respectively.[198]

Rank

|

Name

|

District

|

Pop.

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chennai  Coimbatore |

1 | Chennai | Chennai | 8,696,010 |  Madurai  Tiruchirappalli | ||||

| 2 | Coimbatore | Coimbatore | 2,151,466 | ||||||

| 3 | Madurai | Madurai | 1,462,420 | ||||||

| 4 | Tiruchirappalli | Tiruchirappalli | 1,021,717 | ||||||

| 5 | Tiruppur | Tiruppur | 962,982 | ||||||

| 6 | Salem | Salem | 919,150 | ||||||

| 7 | Erode | Erode | 521,776 | ||||||

| 8 | Vellore | Vellore | 504,079 | ||||||

| 9 | Tirunelveli | Tirunelveli | 498,984 | ||||||

| 10 | Thoothukudi | Thoothukudi | 410,760 | ||||||

Religion and ethnicity

Religion in Tamil Nadu (2011)[199]

The state is home to a diverse population of ethno-religious communities.

Language

Tamil is the official language of Tamil Nadu, while

LGBT rights

The

Culture and heritage

Clothing

Tamil women traditionally wear a

Cuisine

Literature

Tamil Nadu has an independent literary tradition dating back over 2500 years from the Sangam era.[5] Early Tamil literature was composed in three successive poetic assemblies known as the Tamil Sangams, the earliest of which, according to legend, were held on a now vanished continent far to the south of India.[253] This includes the oldest grammatical treatise, Tolkappiyam, and the epics Cilappatikaram and Manimekalai.[254] The earliest epigraphic records found on rock edicts and hero stones date from around the 3rd century BCE.[255]

In the early medieval period,

Architecture

With the

Arts

Tamil Nadu is a major centre for music, art and dance in India.

The ancient Tamil country had its own

The state is home to many museums, galleries, and other institutions which engage in arts research and are major tourist attractions.[302] Established in the early 18th century, Government Museum and National Art Gallery are amongst the oldest in the country.[303] The museum inside the premises of Fort St. George maintains a collection of objects of the British era.[304] The museum is managed by the Archaeological Survey of India and has in its possession, the first Flag of India hoisted at Fort St George after the declaration of India's Independence on 15 August 1947.[305]

Tamil Nadu is also home to the Tamil film industry nicknamed as "Kollywood" and is one of the largest industries of film production in India.[306][307] The term Kollywood is a blend of Kodambakkam and Hollywood.[308] The first silent film in South India was produced in Tamil in 1916 and the first talkie was a multi-lingual film, Kalidas, which released on 31 October 1931, barely seven months after India's first talking picture Alam Ara.[309][310] Samikannu Vincent, who had built the first cinema of South India in Coimbatore, introduced the concept of "Tent Cinema" in which a tent was erected on a stretch of open land close to a town or village to screen the films. The first of its kind was established in Madras, called "Edison's Grand Cinemamegaphone".[311][312][313]

Festivals

Pongal is a major and multi-day harvest festival celebrated by Tamils.[314] It is observed in the month of Thai according to the Tamil solar calendar and usually falls on 14 or 15 January.[315] It is dedicated to the Surya, the Sun God and the festival is named after the ceremonial "Pongal", which means "to boil, overflow" and refers to the traditional dish prepared from the new harvest of rice boiled in milk with jaggery offered to Surya.[316][317][318] Mattu Pongal is meant for celebration of cattle when the cattle are bathed, their horns polished and painted in bright colors, garlands of flowers placed around their necks and processions.[319] Jallikattu is a traditional event held during the period attracting huge crowds in which a bull is released into a crowd of people, and multiple human participants attempt to grab the large hump on the bull's back with both arms and hang on to it while the bull attempts to escape.[320]

Economy

The economy of the state consistently exceeded national average growth rates, due to

The state has a diversified industrial base anchored by different sectors including

- Services

As of 2022[update], the state is amongst the major

The state has two

- Manufacturing

Manufacturing is various states are governed by state owned industrial corporation

Another major industry is textiles with the state being home to more than half of the operating fiber textile mills in India.[365][366] Coimbatore is often referred to as the Manchester of South India due to its cotton production and textile industries.[367] As of 2022[update], Tiruppur exported garments worth $480 billion, contributing to nearly 54% of the all the textile exports from India and the city is known as the knitwear capital due to its cotton knitwear export.[368][369] As of 2015[update], the textile industry in Tamil Nadu accounts for 17% of the total invested capital in all the industries.[370] As of 2021[update], 40% of leather goods exported from India worth ₹92.52 billion (US$1.2 billion) are being manufactured in the state.[371] The state supplies two-thirds of India's requirements of motors and pumps, and is one of the largest exporters of wet grinders with "Coimbatore Wet Grinder", a recognized Geographical indication.[372][373]

There are two ordnance factories in Aruvankadu and

- Agriculture

Agriculture contributes 13% to the GSDP and is a major employment generator in rural areas.

As of 2022[update], the state is a largest producer of

Infrastructure

Water supply

The state accounts for nearly 4% of the land area and 6% of the population, but has only 3% of the water resources of the country and the per capita water availability is 800 m3 (28,000 cu ft) which is lower than the national average of 2,300 m3 (81,000 cu ft).

Water supply and sewage treatment are managed by the respective local administrative bodies such as the

Health and sanitation

The state is one of the leading states in terms of sanitation facilities with more than 99.96% of people having access to toilets.[404] The state has robust health facilities and ranks higher in all health related parameters such as high life expectancy of 74 years (sixth) and 98.4% institutional delivery (second).[196][405] Of the three demographically related targets of the Millennium Development Goals set by the United Nations and expected to be achieved by 2015, Tamil Nadu achieved the goals related to improvement of maternal health and of reducing infant mortality and child mortality by 2009.[406][407]

The health infrastructure in the state includes both government-run and private hospitals. As of 2023[update], the state had 404 public hospitals, 1,776 public dispensaries, 11,030 health centers and 481 mobile units run by the government with a capacity of more than 94,700 beds.

Communication

Tamil Nadu is one of four Indian states connected by

Power and energy

Electricity distribution in the state is done by the

Media

Newspaper publishing started in the state started with the launch of the weekly The Madras Courier in 1785.

Government run

Others

Fire services are handled by the Tamil Nadu Fire and Rescue Services which operates 356 operating fire stations.[453] Postal service is handled by India Post, which operates more than 11,800 post offices in the state.[454] The first post office was established on 1 June 1786 at Fort St. George on 1 June 1786.[455]

Transportation

Road

Tamil Nadu has an extensive road network covering about 271,000 km as of 2023 with a road density of 2,084.71 kilometres (1,295.38 mi) per 1000 km2 which is higher than the national average of 1,926.02 kilometres (1,196.77 mi) per 1000 km2.

| Type | NH | SH | MDR | ODR | OR | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (km) | 6,805 | 12,291 | 12,034 | 42,057 | 197,542 | 271,000 |

There are 48 national highways of length 6,805 kilometres (4,228 mi) in the state and the National Highways Wing of the highways department of Tamil Nadu, established in 1971, is responsbile for the maintenance of

Rail

The rail network in Tamil Nadu forms a part of

| Route length (km) | Track length (km) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broad Gauge | Metre Gauge | Total | Broad Gauge | Metre Gauge | Total | ||

| Electrified | Non electrified | Total | |||||

| 3,476 | 336 | 3,812 | 46 | 3,858 | 5,555 | 46 | 5,601 |

Chennai has a well-established suburban railway network operated by Southern railway, covering 212 km (132 mi) which was established in 1928.

Air and space

The aviation history of the state began in 1910, when

Water

There are three major ports

Education

Tamil Nadu is one of the most literate states in India with a literacy rate was estimated to be 82.9% as per the 2017 National Statistical Commission survey, higher than the national average of 77.7%.[191][494] The state had seen one of the highest literacy growth since the 1960s due to the midday meal scheme introduced on a large scale by K. Kamaraj to increase school enrollment.[495][496] The scheme was further upgraded in 1982 to 'Nutritious noon-meal scheme' to combat malnutrition.[497][498] As of 2022[update], the state has one of the highest enrollment to secondary education at 95.6%, far above the national average of 79.6%.[499] An analysis of primary school education by Pratham showed a low drop-off rate but poor quality of education compared to certain other states.[500]

As of 2022[update], the state had over 37,211 government schools, 8,403 government-aided schools and 12,631 private schools which educate 5.47 million, 2.84 million, and 5.69 million students respectively.

As of 2023[update], there are 56 universities in the state including 24

There are over 870 medical, nursing and dental colleges in the state including 21 for traditional medicine and four for modern medicine.

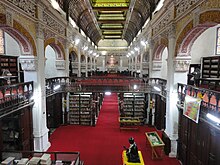

As of 2023[update], the state has 4622 public libraries.[524] Established in 1896, Connemara Public Library is one of the oldest and is amongst the four National Depository Centres in India that receive a copy of all newspapers and books published in the country and the Anna Centenary Library is the largest library in Asia.[525][526] There are many research institutions spread across the state.[527] Chennai book fair is an annual book fair organized by the Booksellers and Publishers Association of South India (BAPASI) and is typically held in December–January.[528]

Tourism and recreation

With its diverse culture and architecture and varied geographies, Tamil Nadu has a robust tourism industry. In 1971, Government of Tamil Nadu established the Tamil Nadu Tourism Development Corporation, which is the nodal agency responsible for the promotion of tourism and development of tourist related infrastructure in the state.[529] It is managed by the Tourism,Culture and Religious Endowments Department.[530] The tag line "Enchating Tamil Nadu" was adopted in the tourism promotions.[531][532] In the 21st century, the state has been amongst the top destinations for domestic and international tourists.[532][533] As of 2020[update], Tamil Nadu recorded the most tourist foot-falls with more than 140.7 million tourists visiting the state.[534]

Tamil Nadu has a 1,076 kilometres (669 mi) long coastline with many beaches dotting the coast.

Sports

Cricket is the most popular sport in the state.

There are multi-purpose venues in major cities including

See also

References

- ^ a b Population and decadal change by residence (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 2. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "The Tamil Nadu Official Language Act, 1956". Act of 27 December 1956 (PDF). Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly. p. 1.

- ^ a b Gross State Domestic Product (Current Prices) (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Per Capita Net State Domestic Product (Current Prices) (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-4470-1582-0.

- ^ "Science News : Archaeology – Anthropology : Sharp stones found in India signal surprisingly early toolmaking advances". 31 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "The Washington Post : Very old, very sophisticated tools found in India. The question is: Who made them?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Skeletons dating back 3,800 years throw light on evolution". The Times of India. 1 January 2006. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ^ T, Saravanan (22 February 2018). "How a recent archaeological discovery throws light on the history of Tamil script". Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ "the eternal harappan script". Open magazine. 27 November 2014. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Shekar, Anjana (21 August 2020). "Keezhadi sixth phase: What do the findings so far tell us?". The News Minute. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "A rare inscription". The Hindu. 1 July 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ "Artifacts unearthed at Keeladi to find a special place in museum". The Hindu. 19 February 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ISBN 978-93-86352-69-9.

- ^ "Three Crowned Kings of Tamilakam". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-8-1317-1120-0.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil (1991). "Comments on the Tolkappiyam Theory of Literature". Archiv Orientální. 59: 345–359.

- Satyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni

- ISBN 978-0-1956-0686-7.

- ^ "The Medieval Spice Trade and the Diffusion of the Chile". Gastronomica. 7. 26 October 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-1990-8832-4.

- ^ T.V. Mahalingam (1981). Proceedings of the Second Annual Conference. South Indian History Congress. pp. 28–34.

- ^ S. Sundararajan. Ancient Tamil Country: Its Social and Economic Structure. Navrang, 1991. p. 233.

- ^ Iḷacai Cuppiramaṇiyapiḷḷai Muttucāmi (1994). Tamil Culture as Revealed in Tirukkural. Makkal Ilakkia Publications. p. 137.

- ^ Gopalan, Subramania (1979). The Social Philosophy of Tirukkural. Affiliated East-West Press. p. 53.

- ISBN 978-0-19-560686-7.

- S2CID 240189630.

- ^ a b "Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "Pandya dynasty". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Jouveau-Dubreuil, Gabriel (1995). "The Pallavas". Asian Educational Services: 83.

- ^ Biddulph, Charles Hubert (1964). Coins of the Cholas. Numismatic Society of India. p. 34.

- ISBN 978-0-6745-4187-0.

- ISBN 978-8-1317-1120-0.

- ISBN 978-0-1430-2989-2.

- ^ a b "Great Living Chola Temples". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Aiyangar, Sakkottai Krishnaswami (1921). South India and her Muhammadan Invaders. Chennai: Oxford University Press. p. 44.

- ISBN 9788122411980.

- Britannica. 30 November 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-1980-3123-9.

- ISBN 978-0-8130-3099-9.

- ISBN 978-8-1215-0224-5.

- ISBN 978-0-5212-5484-7.

- ISBN 978-0-5200-0596-9.

- OCLC 4910527.

- ISBN 978-0-52189-103-5.

- ISBN 978-8-1313-0034-3.

- ISBN 978-0-8364-1262-8.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33538-9.

- ^ Subramanian, K. R. (1928). The Maratha Rajas of Tanjore. Madras: K. R. Subramanian. pp. 52–53.

- ISBN 978-1-9482-3095-7.

- ^ "Rhythms of the Portuguese presence in the Bay of Bengal". Indian Institute of Asian Studies. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Origin of the Name Madras". Corporation of Madras. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "Danish flavour". Frontline. India. 6 November 2009. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ISBN 0-19-564399-2.

- ^ Thilakavathy, M.; Maya, R. K. (5 June 2019). Facets of Contemporary history. MJP Publisher. p. 583.

- ISBN 978-0-1982-6377-7.

- ISBN 978-0-1951-1504-8.

- OCLC 4202160.

- ^ "Seven Years' War: Battle of Wandiwash". History Net: Where History Comes Alive – World & US History Online. 21 August 2006. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ S., Muthiah (21 November 2010). "Madras Miscellany: When Pondy was wasted". The Hindu. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-85109-667-1.

- ^ "Velu Nachiyar, India's Joan of Arc" (Press release). Government of India. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- JSTOR 20203235.

- ^ Caldwell, Robert (1881). A Political and General History of the District of Tinnevelly, in the Presidency of Madras. Government Press. pp. 195–222.

- ISBN 978-8-1269-0085-5.

- ^ "Madras Presidency". Britannica. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ISBN 978-81-313-0034-3.

- ^ "July, 1806 Vellore". Outlook. 17 July 2006. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Pletcher, Kenneth. "Vellore Mutiny". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-1999-9543-1.

- ^ Kolappan, B. (22 August 2013). "The great famine of Madras and the men who made it". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Sitaramayya, Pattabhi (1935). The History of the Indian National Congress. Working Committee of the Congress.

- S2CID 54542458.

Theosophical Society provided the framework for action within which some of its Indian and British members worked to form the Indian National Congress.

- ^ "Subramania Bharati: The poet and the patriot". The Hindu. 9 December 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "An inspiring saga of the Tamil diaspora's contribution to India's freedom struggle". The Hindu. 7 November 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- Madras Legislative Assembly. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "States Reorganisation Act, 1956". Act of 14 September 1953 (PDF). Parliament of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Tracing the demand to rename Madras State as Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. 6 July 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 9788176299664. Archivedfrom the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ V. Shoba (14 August 2011). "Chennai says it in Hindi". The Indian Express. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Krishna, K.L. (September 2004). "Economic Growth in Indian States" (PDF). ICRIER. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Demography of Tamil Nadu (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Patrick, David (1907). Chambers's Concise Gazetteer of the World. W.& R.Chambers. p. 353.

- ^ "Adam's bridge". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Map of Sri Lanka with Palk Strait and Palk Bay" (PDF). UN. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Kanyakumari alias Cape Comorin". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- S2CID 4414279. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- OCLC 58540809. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Eastern Ghats". Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-1281-6097-8.

- ISBN 978-1-1494-8220-9.

- ^ Bose, Mihir (1977). Indian Journal of Earth Sciences. Indian Journal of Earth Sciences. p. 21.

- ^ "Eastern Deccan Plateau Moist Forests". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- ISBN 978-8-1261-1008-7.

- ^ "Centre for Coastal Zone Management and Coastal Shelter Belt". Institute for Ocean Management, Anna University Chennai. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Jenkins, Martin (1988). Coral Reefs of the World: Indian Ocean, Red Sea and Gulf. United Nations Environment Programme. p. 84.

- ^ The Indian Ocean Tsunami and its Environmental Impacts (Report). Global Development Research Center. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Amateur Seismic Centre, Pune". Asc-india.org. 30 March 2007. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Chu, Jennifer (11 December 2014). "What really killed the dinosaurs?". MIT. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ "Deccan Plateau". Britannica. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Strategic plan, Tamil Nadu perspective (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 20. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-1302-0263-5.

- ^ "Farmers Guide, introduction". Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "India's heatwave tragedy". BBC News. 17 May 2002. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-8130-2099-0.

- ^ World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2005.

- ^ "South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 5 January 2005.

- ^ "North East Monsoon". IMD. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-3828-0.

- ^ Annual frequency of cyclonic disturbances over the Bay of Bengal (BOB), Arabian Sea (AS) and land surface of India (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "The only difference between a hurricane, a cyclone, and a typhoon is the location where the storm occurs". NOAA. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Assessment of Recent Droughts in Tamil Nadu (Report). Water Technology Centre, Indian Agricultural Research Institute. October 1995. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Strategic plan, Tamil Nadu perspective (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 3. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Forest Wildlife resources". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ South Western Ghats montane rain forests (PDF) (Report). Ecological Restoration Alliance. Retrieved 15 April 2006.

- ^ "Western Ghats". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Forests of Tamil Nadu". ENVIS. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Biodiversity, Tamil Nadu Dept. of Forests (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Biosphere Reserves in India (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ISBN 978-8-1313-0407-5.

- ^ "Conservation and Sustainable-use of the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve's Coastal Biodiversity". Global Environment Facility. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Baker, H.R.; Inglis, Chas. M. (1930). The birds of southern India, including Madras, Malabar, Travancore, Cochin, Coorg and Mysore. Chennai: Superintendent, Government Press.

- ^ Grimmett, Richard; Inskipp, Tim (30 November 2005). Birds of Southern India. A&C Black.

- ^ "Pichavaram". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Top 5 Largest Mangrove and Swamp Forest in India". Walk through India. 7 January 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Bio-Diversity and Wild Life in Tamil Nadu". ENVIS. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu's 18th wildlife sanctuary to come up in Erode". The New Indian Express. 21 March 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-8155-1133-5.

- Times of India. 2 February 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ^ "Eight New Tiger Reserves". Press Release. Ministry of Environment and Forests, Press Information Bureau, Govt. of India. 13 November 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "Migratory birds flock to Vettangudi Sanctuary". The Hindu. 9 November 2004. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- Indian Express. 7 December 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Guindy Children's Park upgraded to medium zoo". The New Indian Express. 28 July 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Grizzled Squirrel Wildlife Sanctuary". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Singh, M.; Lindburg, D.G.; Udhayan, A.; Kumar, M.A.; Kumara, H.N. (1999). Status survey of slender loris Loris tardigradus lydekkerianus. Oryx. pp. 31–37.

- ISBN 978-9-3508-7269-7.

- ^ "Nilgiri tahr population over 3,000: WWF-India". The Hindu. 3 October 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Malviya, M.; Srivastav, A.; Nigam, P.; Tyagi, P.C. (2011). "Indian National Studbook of Nilgiri Langur (Trachypithecus johnii)" (PDF). Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun and Central Zoo Authority, New Delhi. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- . Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- . Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "State Symbols of India". Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change, Government of India. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Symbols of Tamil Nadu". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ "R. N. Ravi is new Governor of Tamil Nadu". The Times of India. 11 September 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ "MK Stalin sworn in as Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ "Justice SV Gangapurwala sworn in as Chief Justice of Madras HC". The News Minute. 28 May 2023. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "List of Departments". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "Government units, Tamil Nadu". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Local Government". Government of India. p. 1. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Statistical year book of India (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 1. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Town panchayats". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ISBN 978-81-8038-559-9.

- ^ "Indian Councils Act". Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Indian Councils Act, 1909". Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "History of state legislature". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- Times of India. 2 August 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "History of fort". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Term of houses". Election Commission of India. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "History of Madras High Court". Madras High Court. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "History of Madras High Court, Madurai bench". Madras High Court. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu Police-history". Tamil Nadu Police. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Tamil Nadu Police-Policy document 2023-24 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. p. 3. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu Police-Organizational structure". Tamil Nadu Police. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ a b Tamil Nadu Police-Policy document 2023-24 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. p. 5. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Rukmini S. (19 August 2015). "Women police personnel face bias, says report". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu, women in police". Women police India. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Police Ranking 2022 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 12. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ The Tamil Nadu Town and Country Planning Act, 1971 (Tamil Nadu Act 35 of 1972) (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Crime in India 2019 - Statistics Volume 1 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Setup of Election Commission of India". Election Commission of India. 26 October 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-8-1748-8287-5.

- OCLC 249254802.

- ^ "75 years of carrying the legacy of Periyar". The Hindu. 26 August 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "Chief Ministers of Tamil Nadu since 1920". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ASIN B003DXXMC4.

- ^ Marican, Y. "Genesis of DMK" (PDF). Asian Studies: 1.

- ^ The Madras Legislative Assembly, 1962-67, A Review (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "A look at the events leading up to the birth of AIADMK". The Hindu. 21 October 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- hdl:1983/1811.

- ^ "Jayalalithaa vs Janaki: The last succession battle". The Hindu. 10 February 2017. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- The Telegraph. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Hazarika, Sanjoy (17 July 1987). "India's Mild New President: Ramaswamy Venkataraman". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ISBN 978-8-1250-2477-4.

- ^ Decadal variation in population 1901-2011, Tamil Nadu (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Population projection report 2011-36 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 56. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Sex Ratio, 2011 census" (Press release). 21 August 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Fifth National Family Health Survey-Update on Child Sex Ratio" (Press release). Government of India. 17 December 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ State wise literacy rate (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Household Social Consumption on Education in India (PDF) (Report). Government of India. 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Census highlights, 2011 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ SC/ST population in Tamil Nadu 2011 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Population projection report 2011-36 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 25. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Sub-national HDI – Area Database (Report). Global Data Lab. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Life expectancy 2019 (Report). Global Data Lab. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Multidimensional Poverty Index (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 35. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ a b Urban Agglomerations and Cities having population 1 lakh and above (PDF). Provisional Population Totals, Census of India 2011 (Report). Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ Population by religion community – 2011 (Report). The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- ^ "The magic of melting pot called Chennai". The Hindu. 19 December 2011. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "A different mirror". The Hindu. 25 August 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Population by religion community – 2011 (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- New Indian Express. 18 March 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- New Indian Express. 6 November 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- New Indian Express. 20 October 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "The Parsis of Madras". Madras Musings. XVIII (12). 15 October 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Sindhis to usher in new year with fanfare". The Times of India. 24 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Why Oriyas find Chennai warm and hospitable". The Times of India. 12 May 2012. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Chennai's Kannadigas not complaining". The Times of India. 5 April 2008. Archived from the original on 9 June 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "The Anglo-Indians of Chennai". Madras Musings. XX (12). 15 October 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "A slice of Bengal in Chennai". The Times of India. 22 October 2012. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ B.R., Madhu (16 September 2009). "The Punjabis of Chennai". Madras Musings. XX (12). Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Chennai Malayalee Club leads Onam 2023 celebrations". Media India. 1 September 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "When Madras welcomed them". Deccan Chronicle. 27 August 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- New Indian Express. 24 October 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "Migration of Labour in the Country" (Press release). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Census India Catalog (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- . Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Several dialects of Tamil". Inkl. 31 October 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-415-33323-8.

- ISBN 978-0-521-77111-5.

- ^ Akundi, Sweta (18 October 2018). "K and the city: Why are more and more Chennaiites learning Korean?". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020.

- ^ "Konnichiwa!". The Hindu. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ a b "How many tongues can you speak?". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020.

- ^ Akundi, Sweta (25 October 2018). "How Mandarin has become crucial in Chennai". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Guten Morgen! Chennaiites signing up for German lessons on the rise". The Times of India. 14 May 2018. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020.

- Indian Express. 15 December 2013. Archivedfrom the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Hamid, Zubeda (3 February 2016). "LGBT community in city sees sign of hope". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ The Case of Tamil Nadu Transgender Welfare Board: Insights for Developing Practical Models of Social Protection Programmes for Transgender People in India (Report). United Nations. 27 May 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Menon, Priya (3 July 2021). "A decade of Pride in Chennai". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Muzaffar, Maroosha. "Indian state set to be the first to ban conversion therapy of LGBT+ individuals". Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "1st in India & Asia, and 2nd globally, Tamil Nadu bans sex-selective surgeries for infants". The Print. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu Becomes First State to Ban So‑Called Corrective Surgery on Intersex Babies". The Swaddle. 30 August 2019. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Transgenders have marriage rights says Madras High Court". leaflet. 23 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 0-9661496-1-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8109-4461-9.

- ISBN 978-0-2310-7849-8.

- ISBN 978-0-1302-5380-4.

- ^ "About Dhoti". Britannica. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Clothing in India". Britannica. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Weaving through the threads". The Hindu. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ a b Geographical indications of India (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "31 ethnic Indian products given". Financial Express. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- FAO. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-8618-9426-7.

- ISBN 978-0-5202-3674-5.

- ISBN 978-9-7191-7513-1.

- ISBN 978-0-7787-9287-1.

- ^ "Serving on a banana leaf". ISCKON. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "The Benefits of Eating Food on Banana Leaves". India Times. 9 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ISBN 978-8-1737-1293-7.

- (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- JSTOR 3520429.

As early as the Tolkappiyam (which has sections ranging from the 3rd century BCE to the 5th century CE) the eco-types in South India have been classified into

- S2CID 162291987.

- S2CID 144599197.

- ^ "Five fold grammar of Tamil". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ISBN 978-8-120-60955-6.

- ISBN 978-1-000-78039-0.

- ISBN 978-81-7017-398-4.

- ISBN 978-1-350-03925-4.

- ISBN 978-9-351-18100-2.

- ISBN 978-9-380-60721-4.

- ^ Karthik Madhavan (21 June 2010). "Tamil saw its first book in 1578". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Kolappan, B. (22 June 2014). "Delay, howlers in Tamil Lexicon embarrass scholars". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-195-12813-0.

- ^ Arooran, K. Nambi (1980). Tamil Renaissance and the Dravidian Movement, 1905-1944. Koodal.

- ISSN 1305-578X. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-8-1208-0810-2.

- ^ Fergusson, James (1997) [1910]. History of Indian and Eastern Architecture (3rd ed.). New Delhi: Low Price Publications. p. 309.

- ISBN 978-0-4712-6892-5.

- ISBN 978-0-4712-8451-2.

- ISBN 978-0-2265-3230-1.

- ^ "Gopuram". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- Times of India. 7 November 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ISBN 978-9-0602-3607-9

- ISSN 2321-788X. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Metcalfe, Thomas R. "A Tradition Created: Indo-Saracenic Architecture under the Raj". History Today. 32 (9). Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "Indo-saracenic Architecture". Henry Irwin, Architect in India, 1841–1922. higman.de. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "Art Deco Style Remains, But Elements Missing". The New Indian Express. 2 September 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Chennai looks to the skies". The Hindu. Chennai. 31 October 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-8195-6882-3.

- ISBN 978-81-250-1378-5.

- ISBN 978-9-394-70128-1.

- ISBN 978-0-19-816636-8.

- ISBN 978-8-1701-7434-9.

- ISBN 978-9-9919-4155-4.

- ^ The Handbook of Tamil Culture and Heritage. Chicago: International Tamil Language Foundation. 2000. p. 1201.

- ISBN 978-8-1701-7175-1.

- ISBN 978-0-4040-0963-2.

- ISBN 978-8-1212-0809-3.

- S2CID 143220583.

- ISBN 978-81-7835-381-4.

- ISBN 978-9-004-03978-0.

- ^ Widdess, D. R. (1979). "The Kudumiyamalai inscription: a source of early Indian music in notation". In Picken, Laurence (ed.). Musica Asiatica. Vol. 2. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 115–150.

- ISBN 978-8-125-01619-9.

- ISBN 978-0-199-35171-8.

- ISBN 978-1-3045-0409-8.

- ^ Indian Express. 26 July 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- Britannica. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ G, Ezekiel Majello (10 October 2019). "Torching prejudice through gumption and Gaana". Deccan Chronicle. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "CM moots a global arts fest in Chennai". The Times of India. 16 December 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ "For a solid grounding in arts". The Hindu. 3 April 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ "Fort St. George museum". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Indian tri-colour hoisted at Chennai in 1947 to be on display". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu leads in film production". The Times of India. 22 August 2013. Archived from the original on 16 November 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Bureau, Our Regional (25 January 2006). "Tamil, Telugu film industries outshine Bollywood". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-56858-427-0. Archivedfrom the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-415-39680-6. Archivedfrom the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "From silent films to the digital era — Madras' tryst with cinema". The Hindu. 30 August 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ "A way of life". Frontline. 18 October 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ "Cinema and the city". The Hindu. 9 January 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- Times of India. 9 May 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-7007-1267-0. Archivedfrom the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- JSTOR 2797924.

- ISBN 978-93-80325-91-0. Archivedfrom the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

- ISBN 978-0-930741-98-3. Archivedfrom the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- JSTOR 25841633.

- ^ Ramakrishnan, T. (26 February 2017). "Governor clears ordinance on 'jallikattu'". The Hindu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-4042-3808-4.

- ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ISBN 978-1-56308-576-5.

- ISBN 978-81-8205-061-7.

- ISBN 978-8-7911-1489-2.

- ISBN 978-1-0001-8987-2.

- ISBN 978-1-5381-0686-0.

- ISBN 978-81-8094-432-1.

- Indian Express. 5 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Chennai Sangamam to return after a decade". The Times of India. 30 December 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-8195-6906-6.

- ^ Krishna, K.L. (September 2004). Economic Growth in Indian States (PDF) (Report). ICRIER. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu the most urbanised State says EPS". The Hindu. 2 January 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ Rural unemployment rate (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Number of factories (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Engaged workforce (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- Times of India. 15 October 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Industrial potential in Chennai (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Tamil Nadu Budget analysis (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ List of SEZs (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "What India's top exporting states have done right". Mint. 19 July 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Data: Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra & Telangana Account for More Than 80% of India's Software Exports". Factly. 4 July 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Chandramouli, Rajesh (1 May 2008). "Chennai emerging as India's Silicon Valley?". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "PM opens Asia's largest IT park". CIOL. 4 July 2000. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Maharashtra tops FDI equity inflows". Business Standard. 1 December 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- Times of India. 2 May 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Here's why Chennai is the SAAS capital of India". Crayon. 24 August 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- Times of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Investors told to go in for long term investment, index funds". The Hindu. 25 March 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "List of Stock exchanges". SEBI. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Mukund, Kanakalatha (3 April 2007). "Insight into the progress of banking". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Kumar, Shiv (26 June 2005). "200 years and going strong". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- New Indian Express. Archivedfrom the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- New Indian Express. Archivedfrom the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "Indian Bank Head Office". Indian Bank. Archived from the original on 1 August 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "IOB set to takeover Bharat Overseas Bank". Rediff. 28 January 2006. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "RBI staff college". Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Times of India. 5 October 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "TN tops in electronic goods' export". Hindustan Times. 5 July 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "In a first, Tamil Nadu overtakes UP and Karnataka to emerge first". The Times of India. 1 June 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Chennai: The next global auto manufacturing hub?". CNBC-TV18. CNBC. 27 April 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Rediff. 30 April 2004. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-4578-1829-5.

- ^ "Profile, Integral Coach Factory". Indian Railways. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "State wise number of Textile Mills" (Press release). Government of India. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "Lok Sabha Elections 2014: Erode has potential to become a textile heaven says Narendra Modi". DNA India. 17 April 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ "SME sector: Opportunities, challenges in Coimbatore". CNBC-TV18. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ^ "How can India replicate the success of Tiruppur in 75 other places?". Business Standard. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ "Brief Industrial Profile of Tiruppur district" (PDF). DCMSME. Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Industries, Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Sangeetha Kandavel (24 July 2015). "New textile policy on the anvil". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ "TN to account for 60% of India's leather exports in two year". The Times of India. 6 September 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Poor sales hit pump unit owners, workers". The Times of India. 26 May 2015. Archived from the original on 4 June 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^ "Poll code set to hit wet grinders business". Live Mint. 6 August 2015. Archived from the original on 20 August 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ "Seven new defence companies carved out of OFB" (Press release). Government of India. 15 October 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Roche, Elizabeth (15 October 2021). "New defence PSUs will help India become self-reliant: PM". mint. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Pubby, Manu (12 October 2021). "Modi to launch seven new PSUs this week, Defence Ministry approves Rs 65,000-crore orders". The Economic Times. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Ojha, N.N. India in Space, Science & Technology. New Delhi: Chronicle Books. pp. 110–143.

- ^ a b Department of Agriculture, Policy document, 2023-24 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. p. 12. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ State-wise Pattern of Land Use - Gross Sown Area (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ State-wise Production of Foodgrains - Rice (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Thanjavur, history". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ State-wise Production of Non-Foodgrains - Sugercane (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Why Tamil Nadu". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ State-wise Production of Fruits (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ State-wise Production of Vegetables (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "State profile". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Production of Natural Rubber" (Press release). Government of India. 10 July 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Production of Tea in India During And Up to August 2002 (Report). Teauction. 2002. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-4654-3606-1.

- ^ State-wise Production of Eggs (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Agriculture allied sectors (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ State-wise Production of Eggs (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu fisheries department, Aquaculture". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- OCLC 643489739.

- ^ a b Water resources of Tamil Nadu (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. p. 1. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Water resources". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Dam safety". Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Second Master Plan (PDF). Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority. pp. 157–159. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Second Master Plan (PDF). Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority. p. 163. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "IVRCL desalination plant-Minjur". IVRCL. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ Households access to safe drinking water (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ Water resources of Tamil Nadu (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. p. 12. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Swachh Bharat Mission dashboard (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ TN fact sheet, National health survey (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Missing targets". Frontline. 12 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Millennium Development Goals – Country report 2015 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Health department, policy note (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. p. 6. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Medical and health report (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- PMID 33904424. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- Times of India. 28 February 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "The medical capital's place in history". The Hindu. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-84593-660-0.

- ^ "Bharti and SingTel Establish Network i2i Limited". Submarine network. 8 August 2011. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "India's 1st undersea cable network ready". Economic Times. Singapore. 8 April 2002. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "BRICS Cable Unveiled for Direct and Cohesive Communications Services Between Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa". Business Wire. 16 April 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Coimbatore, Madurai, Hosur & Trichy gets ultrafast Airtel 5G Plus services in addition to Chennai". Airtel. 24 January 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b TRAI report, August 2023 (PDF) (Report). TRAI. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- Times of India. 24 January 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu all set for Rs 1,500 crore mega optic fibre network". The New Indian Express. 27 July 2018. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "TANGEDCO, contact". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Chennai ranks second among big cities in power usage". New Indian Express. 1 September 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Per-capita availability of power (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Power consumption". Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Installed power capacity:Southern region (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Installed power capacity (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Chetal, SC (January 2013). "Beyond PFBR to FBR 1 and 2" (PDF). IGC Newsletter. 95. Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research: 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ "Construction of unit 5 & 6 of India's largest nuclear power plant in Kudankulam commences". WION. 17 February 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Nuclear power plants (Report). Atomic Energy Regulatory Board, Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Helman, Christopher. "Muppandal Wind Farm". Forbes. Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "The first newspaper of Madras Presidency had a 36-year run". The Hindu. 25 November 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-8-1709-9082-6.

- ^ Reba Chaudhuri (22 February 1955). "The Story of the Indian Press" (PDF). Economic and Political Weekly.

- ^ "The Mail, Madras' only English eveninger and one of India's oldest newspapers, closes down". India Today. 22 October 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-8-1886-6124-4.

- ISBN 978-0-5202-2598-5.

- ^ Press in India 2021-22, Chapter 9 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 32. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Press in India 2021-22, Chapter 6 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 8. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Press in India 2021-22, Chapter 7 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 5. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "DD Podighai". Prasar Bharti. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "DD Podhigai to be renamed as DD Tamil from Pongal day: MoS L Murugan". DT Next. 10 November 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Sun Group". Media Ownership Monitor. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Arasu Cable to launch operations from September 2". The Hindu. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "BSNL launches IPTV services to its customers in Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. 25 March 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Muthiah, S. (21 May 2018). "AIR Chennai's 80-year journey". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ "All India Radio, Chennai celebrates 85th anniversary". News on Air. 16 June 2002. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 0-8230-5997-9.

- ^ IRS survey, 2019 (PDF) (Report). MRUC. p. 46. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Jayalalithaa govt scraps free TV scheme in Tamil Nadu". DNA India. 10 June 2011. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Romig, Rollo (July 2015). "What Happens When a State Is Run by Movie Stars". New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ "FY-2015: Inflection point for DTH companies in India". India Television. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-0004-7008-6.

- ^ "List of fire stations". Tamil Nadu Fire and Rescue Service. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Post offices of Tamil Nadu (PDF) (Report). India Post. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "History, Tamil Nadu circle". India Post. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Highway policy (PDF) (Report). Highways Department, Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Highways Department renamed as Highways and Minor Ports Department (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ Wings of Highways Department (Report). Highways Department, Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ a b c "Tamil Nadu highways, about us". Highways Department, Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ "National Highways wing". Highways Department, Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Details of national highways (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Highways Circle of Highways Department, Tamil Nadu (PDF) (Report). Highways Department, Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Tamil Nadu STUs (PDF) (Report). TNSTC. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ History of SETC (PDF) (Report). TNSTC. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Number of registered motor vehicles across Tamil Nadu in India from financial year 2007 to 2020 (Report). statista. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ "Southern Railways, about us". Southern Railway. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ Southern Railway. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ "Railways, plan your trip". Tamil Nadu tourism. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- Southern Railway. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ "DNA Exclusive: Is It Time for Indian Railways to Tear Up Ageing Tracks and Old Machinery?". Zee Media Corporation. 14 January 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Sheds and Workshops". IRFCA. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ a b Brief History of the Division (PDF). Chennai Division (Report). Indian Railways—Southern Railways. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ^ List of Stations, Chennai (PDF) (Report). Southern Railway. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "About MRTS". Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "Project status of Chennai Metro". Chennai Metro Rail Limited. 19 November 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "Nilgiri mountain railway". Indian Railways. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Mountain Railways of India". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ^ Indian Hill Railways: The Nilgiri Mountain Railway (TV). BBC. 21 February 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ^ History of Indian Air Force (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 2. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "100 years of civil aviation" (Press release). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-2080-0171-9.

- ^ De Havilland Gazette (Report). De Havilland Aircraft Company. 1953. p. 103.

- ^ "List of Indian Airports (NOCAS)" (PDF). Airports Authority of India. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "List of Indian Airports" (PDF). Airports Authority of India. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ a b Traffic Statistics, September 2023 (PDF) (pdf). Airport Authority of India. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ Regional Connectivity Scheme (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Indian Air Force Commands". Indian Air Force. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Organisation of Southern Naval Command". Indian Navy. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ "ENC Authorities & Units". Indian Navy. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Why Thoothukudi was chosen as ISRO's second spaceport". The News Minute. 2 December 2019. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways, Government of India. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ "Basic Organization". Indian Navy. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Southern naval command". Indian Navy. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu India's most literate state: HRD ministry". The Times of India. 14 May 2003. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Literacy rates (PDF) (Report). Reserve Bank of India. 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Mid-Day Meal Programme". National Institute of Health & Family Welfare. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu: Midday Manna". India Today. 15 November 1982. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Gross enrollment ratio (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Bunting, Madeleine (15 March 2011). "Quality of Primary Education in States". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ^ School education department, policy 2023-24 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "987 out of over 11000 private schools shut". The Hindu. 18 July 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Is Tamil Nadu government sidelining government aided schools". Edex. 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "TN private schools told to teach Tamil for students till Class 10". DT Next. 23 May 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Educational structure". Civil India. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Universities in Tamil Nadu". AUBSP. 8 June 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "A brief history of the modern Indian university". Times Higher Education. 24 November 2016. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020.

- ^ a b Higher education policy report 2023-24 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu: Over 200 engineering colleges fill just 10% seats; 37 get zero admission". The Times of India. 23 August 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Some colleges, schools in Chennai oldest in country". The Hindu. 23 September 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ "Pranab Mukherjee to review passing-out parade at Chennai OTA". The Hindu. Chennai. 27 August 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ Arts college list (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ AICTE Approved Institutions in Tamil Nadu (PDF) (Report). All India Council for Technical Education. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Chennai colleges 100 and counting". The Hindu. 2 August 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Affiliated colleges". Dr MGR university. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Institution History". Madras Medical College. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ "NIRF Rankings 2023: 53 colleges from South India in the top 100". South First. 6 June 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ NIRF rankings 2023 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "How Tamil Nadu's reservation stands at 69% despite the 50% quota cap". News minute. 29 March 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Institution of National Importance". Government of India. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ Working group committee on agriculture (PDF) (Report). Planning Commission of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ "About ICFRE". Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "About Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education". Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ Public library data (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Venkatsh, M. R. (15 September 2010). "Chennai now boasts South Asia's largest library". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "Connemara library's online catalogue launched". The Hindu. 23 April 2010. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "CSIR labs". CSIR. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- Times of India. 8 June 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Tourism,Culture and Religious Endowments Department". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu Tourism Development Corporation Limited" (PDF). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ "Enchanting Tamil Nadu". Government of India. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Tamil Nadu ranks first for domestic tourism: Official". The Economic Times. 10 November 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ India Tourism Statistics 2020 (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ India Tourism statistics-2021 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu beaches". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISBN 90-5809-254-2.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu hill stations". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Ooty: The Queen Of Hill Stations In South India". Print. 22 August 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Ooty". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh build temple ties to boost tourism". The Times of India. 10 August 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Dayalan, D. (2014). Cave-temples in the Regions of the Pāṇdya, Muttaraiya, Atiyamān̤ and Āy Dynasties in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Archaeological Survey of India.

- ^ "Coutrallam". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Waterfalls". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Nilgiri Mountain Railway". Indian Railway. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Mountain Railways of India". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ "Nilgiri biosphere". UNESCO. 11 January 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ siddharth (31 December 2016). "Kabaddi Introduction, Rules, Information, History & Competitions". Sportycious. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-7360-8273-0.

- ^ "Pro Kabaddi League Teams". Pro Kabbadi. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Kabaddi gets the IPL treatment". BBC News. 7 August 2014. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-9363-1701-4.

- ^ Ninan, Susan (6 June 2020). "Back in Chennai, Viswanathan Anand looks forward to home food and bonding with son". ESPN.

- ^ Shanker, V. Prem; Pidaparthy, Umika (27 November 2013). "Chennai: India's chess capital". Aljazeera. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ "Chennai to host first ever Chess Olympiad in India from July 28". Sportstar. 12 April 2022. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Nandanan, Hari Hara (21 August 2011). "Fide offers 2013 World Chess C'ship to Chennai". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-9172-5619-6.

- ^ "Traditional sports and games mark Pongal festivities". The Hindu. Erode, India. 17 January 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-3133-1600-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8784-8099-9.

- ^ "What is Jallikattu? This 2,000-year-old sport is making news in India. Here's why". The Economic Times. 11 January 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ "Pongal 2023: Traditional Bullock Cart Race Held In Various Parts Of Tamil Nadu". ABP News. 17 January 2023. Archived from the original on 25 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ P., Anand (1 January 2024). "Understanding Gatta Gusthi: Kerala's own style of wrestling". Mathrubhumi. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ Raj, J. David Manuel (1977). The Origin and the Historical Development of Silambam Fencing: An Ancient Self-Defence Sport of India. Oregon: College of Health, Physical Education and Recreation, Univ. of Oregon. pp. 44, 50, 83.

- ^ "Top 10 Most Popular Sports in India". Sporteology. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ "MA Chidambaram stadium". ESPNcricinfo. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "International cricket venues in India". The Hindu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Afghanistan To Face Bangladesh In First T20I At Dehradun On Sunday".

- ^ "McGrath takes charge of MRF Pace Foundation". ESPNcricinfo. 2 September 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Times of India. 24 May 2011. Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Times of India. 30 May 2011. Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "Indian Super League: The Southern Derby". Turffootball. 11 July 2020. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "Chennaiyin FC versus Kerala Blasters in ISL's most bitter rivalries". Hindustan Times. 12 November 2016. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "ISL 2020-21: Bengaluru FC renew rivalry with Chennaiyin FC". The Week. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Krishnan, Vivek (22 December 2017). "Chennai City to stay at Kovai for next 5 years". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium, Chennai". SDAT, Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- Times of India. 31 May 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Mayor Radhakrishnan Stadium". SDAT, Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-61530-142-3.

- ^ "The view from the fast lane". The Hindu. 10 April 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Rozario, Rayan (4 November 2011). "Coimbatore may have a Grade 3 circuit, says Narain". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

city, oft referred to as India's motor sport hub, may well have a Grade 3 racing circuit in the years to come

- ^ "City of speed". The Hindu. 24 April 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ "Survivors of time: Madras Race Club - A canter through centuries". The Hindu. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

External links

- Tamil Nadu at Curlie

Geographic data related to Tamil Nadu at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Tamil Nadu at OpenStreetMap