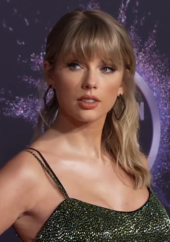

Taylor Swift masters dispute

On June 30, 2019, the American singer-songwriter Taylor Swift entered into a dispute with her former record label, Big Machine Records, its founder Scott Borchetta, and its new owner Scooter Braun, over the ownership of the masters of her first six studio albums.[note 1] It was a highly publicized dispute drawing widespread media coverage and led Swift to release the re-recorded albums—Fearless (Taylor's Version), Red (Taylor's Version), Speak Now (Taylor's Version), and 1989 (Taylor's Version)—from 2021 through 2023 to gain complete ownership of her music.

In November 2018, Swift signed a record deal with Republic Records after her Big Machine contract expired.[note 2] Mainstream media reported in June 2019 that Braun purchased Big Machine from Borchetta for $330 million, funded by various private equity firms. Braun had become the owner of all of the masters, music videos, and artworks copyrighted by Big Machine, including those of Swift's first six studio albums. In response, Swift stated she had tried to purchase the masters but Big Machine had offered unfavorable conditions, and she knew the label would sell them to someone else but did not expect Braun as the buyer, recalling him being an "incessant, manipulative bully".[note 3] Borchetta claimed that Swift declined an opportunity to purchase the masters.

Consequently, Big Machine and Swift were embroiled in a series of disagreements leading to further friction; Swift alleged that the label blocked her from performing her songs at the

Various musicians, journalists, politicians, and scholars supported Swift's stance, prompting a discourse on artists' rights, intellectual property, private equity, and ethics in the music industry. Publications described her response and move to re-record as influential measures, encouraging new artists to negotiate for greater ownership of their music. iHeartRadio, the largest radio network in the United States, proclaimed it will replace the older versions in its airplay with Swift's re-recorded tracks. Billboard named Swift the Greatest Pop Star of 2021 for the successful and unprecedented outcomes of her re-recording venture. Braun has since expressed regret over purchasing Swift's masters and Big Machine at large, and subsequently sold his entire holding company, Ithaca, to Hybe Corporation.

Background

Law

Under

Context

From 2006 to 2017, Swift released six

In August 2018, as per

Ultimately, Swift's contract with Big Machine Records expired in November 2018, following which she signed a new, global contract with Republic Records, a New York-based label owned by Universal Music Group. Variety reported that Swift's catalog constituted around 80 percent of Big Machine's revenue.[20] Swift revealed a negotiation as part of her Republic contract—any sale of Universal's shares in Spotify, the largest on-demand music streaming platform in the world, resulted in equity shares for all of Universal's artists on a non-recoupable basis.[15] The contract also allowed Swift to fully own the albums distributed by the label—both the masters and the publishing rights—starting with her seventh studio album, Lover (2019),[5] and as reported by Forbes, offered a royalty payment of 50 percent or more compared to the 10 to 15 percent Swift "likely" had been receiving from Big Machine.[21]

Dispute

Acquisition by Braun

Scooter and I have been aligned with 'big vision brings big results' from the very first time we met in 2010. Since then I have watched him build an incredible and diverse company that is a perfect complement to the Big Machine Label Group. Our artist-first spirit and combined roster of talent, executives, and assets is now a global force to be reckoned with. This is a very special day and the beginning of what is sure to be a fantastic partnership and historic run.

– Scott Borchetta on selling Big Machine to Scooter Braun[22]

Swift's response

For years I asked, pleaded for a chance to own my work. Instead I was given an opportunity to sign back up to Big Machine Records and 'earn' one album back at a time, one for every new one I turned in. ... I learned about Scooter Braun's purchase of my masters as it was announced to the world. All I could think about was the incessant, manipulative bullying I've received at his hands for years.

On June 30, 2019, Big Machine announced via social media that the label group had been acquired by Braun, following which Swift denounced the acquisition on Tumblr the same day. She stated that she had tried to buy her masters for years, but was not given a chance unless she signed another contract that would require her to create six more albums under the label in exchange for the masters of the first six, which she felt was "unacceptable". While she knew that Big Machine was for sale, she said she was unaware that Braun—whom she described as an "incessant, manipulative bully"—would be the buyer: "Essentially, my musical legacy is about to lie in the hands of someone who tried to dismantle it".[2] She highlighted Braun's involvement in the creation of West's music video for his 2016 single "Famous", which she described as "a revenge porn music video which strips [her] body naked".[5] Swift also claimed that Braun influenced Kim Kardashian, then-married to West, to orchestrate an "illegally recorded" snippet of Swift's phone call with West, and had "two of [Braun's] clients" collude to bully Swift online, referring to a FaceTime screenshot of Bieber, West and Braun, posted to Bieber's Instagram after Kardashian released the snippet.[26][27] Swift accused Borchetta of betraying her loyalty for selling the masters to Braun despite being aware of Braun's role in antagonizing Swift.[15] Passman argued that Borchetta never gave Swift "an opportunity to purchase her masters, or the label, outright with a check in the way [Borchetta] is now apparently doing for others".[28]

Borchetta's reply

In response, Borchetta published a blog post titled "It's Time For Some Truth" on the Big Machine website.[15] On June 25, 2019, Big Machine shareholders and Braun's Ithaca Holdings held a phone call regarding the transaction. While Swift's father Scott was one of the label's minority shareholders (4 percent),[2] he did not join the call due to a "very strict" non-disclosure agreement. A final call was held on June 28, when Scott Swift was represented by a lawyer from Swift's management company, 13 Management.[15] Borchetta said he texted Swift on June 29, claiming that she was aware of Braun's transaction beforehand.[29] He denied that Braun had been hostile toward Swift,[30] and posted a text message he alleged Swift had sent before signing to Republic Records; in the message, Swift said she would accept another seven-year contract with Big Machine on the condition that she took ownership of her audiovisual works. Borchetta agreed, but asked for a ten-year contract. The authenticity of the message has not been verified.[15]

Further strife

On November 14, 2019, Swift accused Braun and Borchetta of preventing her from performing her older songs at the American Music Awards of 2019 and using older material for her 2020 documentary Miss Americana.[31] She said they were "exercising tyrannical control" over her music, and claimed Borchetta told her team that she would be allowed to use the music only if she agreed to not re-record "copycat versions" of her songs; Swift commented, "the message being sent to me is very clear. Basically, be a good little girl and shut up. Or you'll be punished."[32]

In response, Big Machine rejected Swift's claim, "we have worked diligently to have a conversation about these matters with Taylor and her team to productively move forward. However, despite our persistent efforts to find a private and mutually satisfactory solution, Taylor made a unilateral decision last night to enlist her fanbase."[32] However, on November 18, the label issued a statement saying they had "agreed to grant all licenses of their artists' performances to stream post show and for re-broadcast on mutually approved platforms" for the AMAs, without naming Swift.[33] It also stated that Big Machine negotiated with the AMAs producer, Dick Clark Productions (DCP). DCP denied agreeing to issue any statement with Big Machine.[34]

Swift's publicist Tree Paine released a statement the next day. Paine said Swift avoided performing her older songs at the Tmall Double Eleven Gala 2020, a Singles Day event in Shanghai, China, and sang only three songs from Lover, because "it was clear that Big Machine Label Group felt any televised performance of catalog songs violated her agreement",[32] attaching a screenshot of a portion of an alleged email from Big Machine that reads: "Please be advised that [Big Machine] will not agree to issue licenses for existing recordings or waivers of its re-recording restrictions in connection with these two projects: The Netflix documentary and The Alibaba 'Double Eleven' event."[35] Paine also denied Big Machine's statement that said Swift "has admitted to contractually owing millions of dollars and multiple assets" to the label, and claimed the label is attempting to deflect from "the $7.9 million of unpaid royalties" that the label owes to Swift "over several years", as assessed by "an independent, professional auditor".[32] Swift performed six songs at the 2019 AMAs on November 24, 2019, four of which were from her first six albums,[note 7] and received the Artist of the Decade award.[37]

In April 2020, Big Machine released Live from Clear Channel Stripped 2008, a live album of Swift's performances at a 2008 radio show. Swift said she did not authorize the release, and dismissed it as "just another case of shameless greed in the time of Coronavirus".[38] Live from Clear Channel Stripped 2008 earned only 33 units in the US and did not chart anywhere.[39] From August 2019 to January 2020, Big Machine released 4,000 vinyl LPs of each of the singles from Taylor Swift for the album's 13th anniversary, which was met with immediate backlash from Swift's supporters.[40][41]

Aftermath

Swift's solution to her crisis was to create new recordings of all of the musical work in the six albums, using the publishing rights she retained, and to have the finished product sound as close to the original as possible.

Sale to Shamrock

In October 2020, Braun sold the masters, associated videos and artworks to

Swift's re-recordings

Swift began releasing her re-recorded music in 2021. The re-recorded albums and songs are identified by the note "(Taylor's Version)" added to all of their titles, to distinguish them from the older recordings.[54]

In February 2021, Swift announced that she had finished re-recording Fearless and released "

On November 12, 2021, Swift released

In March 2023, ahead of the

1989 (Taylor's Version) was released on October 27, 2023.[76] Globally, it garnered the highest single-day streams for an album in 2023 on Spotify,[77] and its tracks occupied the top six of the Billboard Global 200 concurrently, making Swift the first artist to do so.[78] In the US, 1989 (Taylor's Version) became Swift's record-extending sixth album to sell one million copies in a single week,[79] and surpassed Midnights, her tenth studio album, for the highest first-week vinyl sales of the 21st century.[80] 1989 (Taylor's Version) debuted atop the Billboard 200 with over 1.6 million units, surpassing the original 1989's first-week figures by 400,000 units, and marked the largest album sales week of Swift's career and the 2020s decade.[81] The vault tracks "Is It Over Now?", "Now That We Don't Talk", and "'Slut!'" occupied the top three spots of the Hot 100 in that order.[82]

Press investigation

On November 16, 2020, Variety journalist Shirley Halperin reported, "some insiders speculate the value [of Swift's masters] could be as high as $450 million once certain earn-backs are factored in".[46] According to a November 2021 report by Financial Times, Braun believed that Swift was "just bluffing" about re-recording. The newspaper stated that, after purchasing Big Machine, Braun began searching for buyers for the masters of Swift's back catalog, and that he and co-investors told potential buyers that Swift would not actually re-record the albums, calling her announcement an "empty threat"; Braun also told the buyers that Swift's posts about the dispute would only generate more publicity, boosting streams and downloads of the albums. Financial Times also alleged that the deal between Braun and Shamrock included "a post-purchase earnout to Braun and Carlyle Group, if sales and streams hit specific targets".[83] On December 10, 2021, The New York Times published that the Carlyle Group contacted Braun and encouraged him to reach a ceasefire with Swift, such as a joint-venture partnership, to prevent her from re-recording, according to an undisclosed group of "four people close to the situation", three of whom said the firm was "unhappy to be dragged into the dispute in such a public way".[84]

Sale of Ithaca

In April 2021, Braun merged Ithaca with South Korean entertainment company Hybe Corporation, which purchased Ithaca for a 100 percent stake through its wholly owned subsidiary, Hybe America. The deal, valued at $1 billion, brought the SB Projects and Big Machine rosters, including Bieber, Grande, Lovato, J Balvin, Thomas Rhett, Florida Georgia Line, and Lady A, together with K-pop acts like BTS, Tomorrow X Together, and Seventeen. Braun joined the board of Hybe.[87] In a September 2022 interview with NPR's Jay Williams, Braun stated he regrets the way the Big Machine acquisition was handled, admitted he came from a "place of arrogance" when he assumed that he and Swift "could work things out", and that he learned "an important lesson". Braun also stated that he was forced to make the purchase under a "very strict NDA" and hence was not allowed to talk to anybody about it.[88][89]

Reactions

The controversy was highly publicized, drawing reactions and critiques from across the internet. Swift's re-recordings were one of the most widely discussed and covered news topics of 2020–2021, and were described by media outlets as one of 2021's most prominent pop-culture events.[90] Evening Standard called it "music's biggest feud", because "back catalogues regularly change hands behind the scenes, but almost never make headlines".[16] Hashtags "#IStandWithTaylor" and "#WeStandWithTaylor" trended worldwide on Twitter following Swift's post.[32][91][5] Billboard wrote, since the controversy, acts "lined up for Team Swift or Team Braun, creating the most public battle about an artists' masters in recent memory".[19]

Entertainment industry

Swift's response and social media posts sparked support from many of her contemporaries. Musicians who openly supported her include

A few musicians supported Braun, including Australian singer-songwriter Sia,[97] American singer Ty Dolla Sign, and Braun's clients Bieber and Lovato. Lovato and Sia said they believe Braun is a "good man" and that his actions were not personal.[5][105] American entertainer Todrick Hall, who was formerly a client of Braun, supported Swift and accused Braun of homophobia; Hall engaged in a back-and-forth argument with Lovato on Twitter. In an Instagram post, Bieber apologized to Swift for the FaceTime screenshot (with Braun and West) he posted in 2016 with a caption targeting her; however, Bieber defended Braun, saying Braun has supported Swift since she let Bieber be the opening act of her Fearless Tour and added "years have passed, we haven't crossed paths and gotten to communicate our differences, hurts or frustrations. So for you to take it to social media and get people to hate on Scooter isn't fair." Bieber's wife Hailey called him a "gentleman" under the post, which prompted Delevingne to criticize the Biebers for what she considered as insincere amity. Grande, also a client of Braun, posted an Instagram story congratulating Braun on the purchase but deleted it after Swift posted her statement.[94] David Geffen, a music executive whom Braun has often described as a mentor, supported Braun but said "only time will tell who made the wise decision".[29]

Politicians

On November 19, 2019, US senator

American businessman Glenn Youngkin was the former co-CEO of the Carlyle Group, the major sponsor in Braun's purchase of Big Machine and Swift's masters. Youngkin contested in the 2021 Virginia gubernatorial election as the Republican candidate for the office of the Governor of Virginia. On October 6, 2021, ahead of the election, former governor and Democratic candidate Terry McAuliffe launched a series of negative advertisements on Facebook, Instagram, and Google Search, tying Youngkin to the purchase. The ad included the slogan "#WeStandWithTaylor", a hashtag used by Swifties during the fallout of the dispute, and asked her supporters to vote for McAuliffe.[108][109] Youngkin's spokesperson, Christian Martinez, stated "McAuliffe has reached the stage of desperation in his campaign where he's rolling out the most baseless attacks to see what sticks". Additionally, NPR highlighted a July 2021 report by Associated Press that claimed McAuliffe himself had invested a minimum of $690,000 in Carlyle between 2007 and 2016. McAuliffe's spokesperson, Renzo Olivari, confirmed that McAuliffe was a "passive" Carlyle investor who by 2019, at the time of the sale of the masters, owned less than $5,000 in Carlyle stock.[108]

Music critics

Publications highlighted Swift's public opposition to the acquisition as trailblazing: while the issue of master ownership and the conflicts between record labels and artists such as Prince, the Beatles, Janet Jackson, and Def Leppard have been prevalent, Swift was one of the few to make it public.[6][29][112][113] Rolling Stone journalists described the dispute as one of the 50 "most important moments" of the 2010s.[114] Dominic Rushe of The Guardian said Swift's situation hinted at a change in the digital music era, where artists are more informed of their ownership and would not rely on record labels for marketing as heavily as in the past.[113] Recognizing the visibility she brought to "one of the music industry's longest standing issues", Pitchfork critic Sam Sodomsky said Swift "is also so huge—not just an artist but a brand—that she can enact change by wielding the leverage of the reliability of her success", and that when she makes a statement, it is "financially lucrative for the industry to listen".[112] The Evening Standard's Katie Rosseinsky wrote, "it is not just another celebrity feud, this could have wide-reaching repercussions for the music industry."[16]

Critical commentary on Swift's decision to re-record remained favorable as well.

Unlike most artists when faced with this kind of injustice, Swift actually had the ability to stand up for herself, and in doing so, invoke meaningful dialogue and inspire change within the notoriously slow-moving music industry ... Re-recording a back catalogue of six full albums and respective secret bonus tracks, then developing a hugely successful campaign to drive loyal fans towards the new versions of their beloved albums—and away from the original master recordings, prompting a dip in streams that will be mimicked in the rights holders' income statement—is something only very, very few artists can do. Taylor Swift is, indeed, amongst that handful.

— Eilish Gilligan, Taylor Swift's Re-Recordings Expose The Music Industry's Chokehold On Intellectual Property, Refinery29[123]

The Wall Street Journal journalist Neil Shah wrote, for using her back catalog in mass media, such as for commercials and movies, Swift can shut out Shamrock and Braun by directly lending the concerned song to the third party, approving the copyright license herself.[17] Kate Dwyer of Marie Claire said the re-recorded albums free Swift from the sexist tabloid scrutiny of her private life that overshadowed her past works, by re-introducing listeners and critics to the same songs but without "as much gender bias", and that the audiences who "didn't believe she was a feminist before (for whatever, sexist reason) can't deny the feminist undertones of becoming the industry spokesperson for artists' rights."[124]

Legal scholars

Various lawyers and law firms have published their analyses of the controversy. The majority highlighted the lack of legal grounds and that a lawsuit is not viable. Susan H. Hilderley, music attorney at University of California's Los Angeles School of Law, told The Washington Post that Swift not owning her masters is "nothing out of the ordinary". Hilderley noted Swift was an unknown artist when she signed her record deal and that signing off the masters to the record label is the "kind of terms" usually followed in artist-label agreements.[125] In a similar vein, Erin M. Jacobson, a music attorney specializing in artist-label negotiations, said on CBC News that "the structure of a label owning the master has been in place for such a long time that a lot of people are just used to that". She affirmed that Swift has no legal recourse on the contract but can effect change in the music industry and benefit all artists.[126]

The Hollywood Reporter consulted music lawyers Howard King and Derek Crownover regarding the controversy; King said Swift would not sue Braun or the label because of the "personal" nature of the dispute—her predicament being not the sale itself but that Braun is the buyer—having no legal recourse. In agreement, Crownover said: "from the satellite view, I don't see any legal ramifications that could come of this, unless there were restrictions on the sale of the masters to third parties."[28] James Jeffries-Chung of Norton Rose Fulbright asserted Shamrock cannot prevent Swift from re-recording her music by any legal measure since she is the publisher of her songs and that all they can hope is "listeners may be less interested in hearing modern takes of songs they enjoyed a decade ago and stick with the originals."[127]

Any time Taylor brings attention to an issue, it gets magnified ... She has a very loud megaphone and she's not afraid to use it. She's had great success in effectuating change.

— James Sammataro, music attorney, The Hollywood Reporter[28]

Many opined that Swift's moves will bring about systemic changes in the music industry and artist-label relationships. Meredith Rose, senior policy counsel at Public Knowledge, wrote in her American Bar Association post that "if Swift—who is, without exaggeration, one of the biggest powerhouse pop stars of an entire generation—can't get her own masters back, who could? Turns out, almost nobody."[122] According to Tonya Butler, professor and chair of the Music Business Management Department at Berklee College of Music, "regardless of the reasons why [Swift is] re-recording, whether it's spite or good business, the fact she is bringing to attention the re-recording restriction agreement alone makes the whole controversy valuable."[4] McBrayer's Peter J. Rosene stated that each "Taylor's Version" album lowers the value of the master of its respective original held by Shamrock and predicted that the sales of the re-recordings "might, in fact, outperform the original albums."[128] Justin Tilghman of the University of Georgia School of Law opined that the clause that prohibits an artist from re-recording their own songs for a designated period of time can "go too far and, in effect, violate the public policy the Framers had in mind when drafting the Useful Art Clauses."[129]

American author Steve Stoute said "you build it; we make you think that you own it; you act like you own it; but at the end of the day, we own it." He opined that Swift's dilemma is a "painful" illustration of the fundamental issue with the music business that has been following a "sharecropping" model.[29] According to professor R. Polk Wagner of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, Swift associating her lyrics with a range of goods and services through trademark applications represents her understanding that "she is bigger than the music". He added "it's more of a branding right, thinking of Taylor Swift as a conglomerate."[130] Doug McMahon of Irish firm McCann Fitzgerald LLP opined that the controversy shows how "the bundle of related copyrights that exist in a piece of music can give rise to complex disputes" and upheld Swift's move to re-record as a "relatively novel solution", in regards to the copyright legislations in Ireland.[131]

Legacy

Recognition

At the 2019 Billboard Women in Music event, Swift was conferred the inaugural Woman of the Decade award for the 2010s. In her acceptance speech, Swift addressed Braun for the first time publicly, criticizing his "toxic male privilege" and the "unregulated world of private equity coming in and buying [artists'] music as if it's real estate—as if it's an app or a shoe line." She claimed that none of the investors "bothered to contact me or my team directly—to perform their due diligence on their investment; on their investment in me. To ask how I might feel about the new owner of my art, the music I wrote, the videos I created, photos of me, my handwriting, my album designs."[132]

In December 2021, Billboard recognized Swift as "The Greatest Pop Star of 2021", saying she "rewrote industry rules and had one of the most impactful years of her storied pop career without even releasing an entirely new album." The magazine stated that the "unequivocal success" of Fearless (Taylor's Version) and Red (Taylor's Version) prove the widespread acceptance of the recordings, which replaced the older versions as "the ones listeners will be digesting and caring about moving forward."

The term "(Taylor's Version)" and its variants have since achieved cultural prominence as taglines.[138] Organizations such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and National Football League (NFL) have since used or parodied the term in their promotional digital content.[139][140]

Financial impact

The re-recordings were widely successful.[133][141] The original Fearless was charting at number 157 on the US Billboard 200 chart before the impact of Fearless (Taylor's Version), after which the original dropped 19 percent in sales and fell off the chart completely, while the re-recording debuted at number one. Ben Sisario of The New York Times opined that Fearless (Taylor's Version) "accomplished what appeared to be one of Swift's goals: burying the original Fearless."[142][143] This became a pattern: Each announcement of a Taylor's Version album caused a spike in interest in the original album, but upon release of the new recording, the original plummeted in consumption and exited the chart; the original Red dropped by 45 percent, Speak Now by 59 percent and 1989 by 44 percent, following the release of their respective re-recordings.[144][145] In October 2023, Bloomberg News estimated the value of the four re-recordings to be $400 million.[146]

The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry reported that Swift was the world's best-selling soloist and female artist of 2021.[147] Forbes estimated her 2021 earnings to be US$52,000,000,[148] and opined that Swift "recreating her catalog also sets [her] up for a potentially massive payday".[21] Her publication rights over her first six albums were valued at $200 million in 2022.[149] Rolling Stone reported in January 2022 that Swift was the highest-paid female musician of 2021, owing to Fearless (Taylor's Version) and Red (Taylor's Version), ahead of artists who released brand new albums that year.[150] In December 2022, Billboard reiterated that Swift was the top earning musician overall in 2021, taking home an estimated $65.8 million, followed by English band the Rolling Stones ($55.5 million).[151]

Synchronization

Every week, we get a dozen synch requests to use "Shake It Off" in some advertisement or "Blank Space" in some movie trailer, and we say no to every single one of them. And the reason I'm rerecording my music next year is because I do want my music to live on. I do want it to be in movies, I do want it to be in commercials. But I only want that if I own it.

Swift has pointedly refused to authorize synchronization requests for the original versions of her songs from her first six albums, advising use of her re-recorded versions instead.[48] American actor and Swift's brother, Austin, manages the licensing of her songs.[48] A cover version of "Look What You Made Me Do" (2017), the lead single of Reputation, was featured in the opening credits of an episode (aired May 24, 2020) of spy thriller series Killing Eve. The artist credited as the performer of the cover, Jack Leopards & the Dolphin Club, had no documented existence before the song's release. It was fronted by an unnamed male vocalist, speculated by some media outlets to be Austin,[152] and was produced by Jack Antonoff and Nils Sjöberg, the latter being a pseudonym of Swift.[153] Because Swift could not re-record Reputation at the time the episode aired, some believed that the cover version was Swift's way of bypassing the potential issues that would arise with Big Machine over licensing the copyright to Killing Eve. A copyright license is mandatory for using a song in a visual work; otherwise, the owner of the copyright is allowed to fine or press charges against the party who used the song unlicensed.[154][155]

The re-recorded tracks have been featured in various visual media: "Love Story (Taylor's Version)" appeared in an advertisement produced by Canadian actor

According to Billboard, filmmakers are aware that "Swift songs in scenes or trailers instantly build

Fan action

Journalists and media outlets credited Swift's fans, known commonly as "Swifties", with aiding Swift in magnifying the publicity surrounding the controversy and the success of her re-recording efforts.[117][160][161] Whereas, Braun claimed that Swift "weaponized" her fanbase by making the dispute public.[162]

On June 30, 2019, following the news that Braun had acquired Big Machine—and along with it Swift's back catalog—many of Braun's friends congratulated him on their social media accounts; American entrepreneur

Fans also mined information about the Carlyle Group and claimed it has ties to

Peer acknowledgment

American singer-songwriter Olivia Rodrigo stated that she negotiated with her record label to own her music's masters herself, after observing Swift's battle,[168] and British singer Rita Ora thanked Swift for providing an incentive to purchase her masters herself.[169] American singer Joe Jonas said that he wishes to re-record the Jonas Brothers' back catalog just like Swift.[170] Canadian musician Bryan Adams, American vocal group 98 Degrees and American rock band the Departed were inspired by Swift to re-record.[171][172][173] American musician Dave Grohl, frontman of the rock band Foo Fighters, said he was "deeply impressed" by Swift and supports her vision.[174] American rapper Snoop Dogg cited Swift's re-recordings and stated he wanted to re-record his debut album, Doggystyle (1993), but could not bring himself to do it because he was unable to replicate the "feeling".[175] American singer-songwriter Ashanti announced her intention to re-record her self-titled debut album to gain its masters, and told Metro that she felt "empowered" by Swift; Ashanti further stated "I think Taylor is amazing for what she's done and to be able to be a female in this very male-dominated industry, to accomplish that is amazing. Owning your property and getting a chance to have ownership of your creativity is so so important. Male, female, singer, rapper, whatever, I hope this is a lesson for artists to get in there and own."[176]

Indonesian singer-songwriter Niki stated Swift inspired her to re-record and "reimagine" her original songs that she had deleted from YouTube after signing to her record label, incorporating them into her second studio album, Nicole (2022).[177] American socialite Paris Hilton released an "updated" version of her 2006 song, "Stars Are Blind", re-titled as "Stars are Blind (Paris' Version)", on December 30, 2022.[178] American singer SZA praised Swift in her 2023 Billboard Woman of the Year interview: "Taylor letting that whole situation go with her masters, then selling all of those fucking records. That's the biggest 'fuck you' to the establishment I've ever seen in my life, and I deeply applaud that shit."[179] American rapper Offset, a former member of hip hop group Migos, claimed to be "rap's Taylor Swift" following a dispute with Quality Control Music, his former record label, over his solo career. He has said he is seeking "control over his master recordings".[180] Irish actress Saoirse Ronan and American filmmaker Greta Gerwig said Swift's fight for ownership resonated with them while making the 2019 film adaptation of Little Women, whose author Louisa May Alcott also held onto her copyright.[181] American musician Melissa Etheridge called the re-recording project "probably the most impressive musical business feat I've ever seen. Ever."[182] British musician Imogen Heap called the project "a badass card to stay in control of [Swift's] work in a commercial music industry that largely works against musicians."[183] American singer and songwriter Maren Morris said she found "deep inspiration" in Swift's "courage" "turning the tables on exploitative businessmen and taking back ownership".[184] In 2023, The Guardian opined that "a revolution is brewing in the music business", witnessing a new generation of female artists, such as Zara Larsson, Dua Lipa, and Rina Sawayama, following Swift's precedence to acquire ownership of their music rights and maintaining a defiant attitude towards forfeiting all rights to the music label.[185]

Systemic changes

Swift is one of few artists with the power and profile to create change in the music world—when she acts, the industry listens. In reclaiming her masters, and drawing attention to the saga surrounding it, she has made a dramatic statement about the importance of artists owning their work and refusing to let others capitalise on their creativity. Sure, she's a

multi-millionaire but in using her platform in this way, she's galvanising other, less established artists to fight for a better deal.— Katie Rosseinsky, "How Taylor Swift is changing the music industry one re-record at a time", Evening Standard[16]

On November 12, 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that Universal Music Group, the parent company of Swift's current label, has doubled the amount of time that restricts artists from re-recording their works in their recording deals hereafter. The newspaper said the change represents "shifting power dynamics in the music business", as artists have started to demand better revenue shares and ownership of the masters to their music, incentivized by Swift's situation.[186] Weverse said "the recording industry had been watching [Swift's] rerecording project closely to see where it might go and has recently begun to react" and pointed out that musicians have started to demand the rights to their masters "more and more often" following the controversy.[187] On November 17, 2021, iHeartRadio announced that its radio stations will only play "Taylor's Version" songs henceforth, with plans to replace the rest of the older recordings with the re-recorded tracks as they are officially released.[188]

Following the success of Swift's re-recordings, record labels and companies began to contractually prohibit music artists from ever re-recording their songs or increasing the waiting period to 10–30 years. In October 2023, Billboard reported that the major labels—Universal, Sony Music Entertainment and Warner Music Group—overhauled clauses on re-recording in the contracts for new signees, with several music attorneys opposing this change.[189] Additionally, more artists have moved toward a licensing deal where they retain control of the masters, though traditional contracts where the label owns the masters remain more common.[189] In January 2024, The Guardian reported that the retention periods for music publishing is down from 25 years three decades ago to between 12 and 15 years. According to music industry journalist Eamonn Forde, the publishing part of the music business was "ahead of the curve." On the other hand, label re-recording restrictions are getting longer after the Taylor Swift issue, and that labels do not want re-records, they need to protect their assets. "They don"t want their product replaced by something else", stated music industry attorney Erin M. Jacobson. However, in order "to stay competitive, the traditional labels have to consider some alternate structures or terms that are a little more artist-friendly", she said.[190]

Music inspiration

Songs from each of Swift's 2020 albums, "

Academic attention

The controversy has also been a topic of study in higher educational institutions. On October 4, 2021, Rafael Landívar University in Guatemala hosted a conference on the topic "International Copyright Protection: Analyzing Taylor Swift's Case".[198] In January 2022, a spring semester course focusing on Swift's career and its cultural impact was launched at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts, with "copyright and ownership" as one of the topics covered by the syllabus.[199] Queen's University at Kingston offers a fall semester course, titled "Taylor Swift's Literary Legacy (Taylor's Version)", focusing on her sociopolitical impact on contemporary culture; its syllabus includes studying select songs from Swift's studio albums, with the use of re-recorded versions wherever possible.[200] The University of Virginia Darden School of Business released a new case study on the masters controversy in September 2023.[201] In November 2023, the University of South Dakota announced a law course centered around Swift's interactions with the law, which will examine her re-recordings and related copyright issues.[202]

See also

- Cultural impact of Taylor Swift

- Taylor Swift sexual assault trial

- 2022 Ticketmaster controversy

Footnotes

- ^ Namely, Taylor Swift (2006), Fearless (2008), Speak Now (2010), Red (2012), 1989 and Reputation (2017).[1]

- studio albums under Big Machine. Therefore, following the cessation of the promotional activities for her sixth studio album, Reputation (2017), the contract officially expired in November 2018.[2]

- ^ This is an excerpt from the lengthy post Swift made on Tumblr,[3] and is not meant to condense or summarize her entire statement.

- ^ investment firm. The family completely owns Shamrock and remains its sole investor.[47]

- ^ The Big Machine Label Group encompasses Big Machine Records, The Valory Music Co., BMLG Records, Big Machine/John Varvatos Records, publishing company Big Machine Music, and digital radio station Big Machine Radio.[18]

- ^ According to The New York Times, the Carlyle Group owned about one-third of Ithaca Holdings and contributed "a significant sum" for the purchase.[25]

- ^ Swift performed a medley of "The Man" (2020), "Love Story" (2008), "I Knew You Were Trouble" (2012), "Blank Space" (2014), "Shake It Off" (2014) with singers Camila Cabello and Halsey, and "Lover" (2019) featuring American ballet dancer Misty Copeland.[36] The shirt Swift wore for "The Man" and the piano she played for "Lover" displayed the titles of the six albums.[37]

- ^ Swift's recording contract with Big Machine stipulates that she shall be able to re-record a song or an album only after five years since their respective release dates. For instance, Fearless was released on November 11, 2008, and thus it had been eligible for re-recording since November 11, 2013.[16]

- ^ Swift and Gomez regard each other as one of their greatest friends and have expressed their admiration for each other numerous times in the media since 2008. Their friendship has been widely covered by media outlets and mainstream publications.[85]

References

- ^ McGrath, Rachel (August 11, 2023). "Taylor Swift's Rerecordings Explained: This Is Why She's Releasing 'Taylor's Versions'". HuffPost. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Finnis, Alex (November 17, 2020). "Taylor Swift masters: The controversy around Scooter Braun selling the rights to her old music explained". i. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Taylor Swift on Tumblr". June 30, 2019. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ from the original on November 15, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grady, Constance (July 1, 2019). "The Taylor Swift/Scooter Braun controversy, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Glynn, Paul (July 1, 2019). "Taylor Swift v Scooter Braun: Is it personal or strictly business". BBC. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- CMT. November 26, 2008. Archivedfrom the original on January 23, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ Malec, Jim (May 2, 2011). "Taylor Swift: The Garden In The Machine". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Taylor Swift: The Garden In The Machine". American Songwriter. May 2, 2011. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Songwriter Taylor Swift Signs Publishing Deal With Sony/ATV". Broadcast Music, Inc. May 12, 2005. Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ DeLuca, Dan (November 11, 2008). "Focused on 'great songs' Taylor Swift isn't thinking about 'the next level' or Joe Jon as gossip". Philadelphia Daily News. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 18, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ Willman, Chris (July 25, 2007). "Getting to know Taylor Swift". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- CMT. Archivedfrom the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Rapkin, Mickey (July 27, 2017). "Oral History of Nashville's Bluebird Cafe: Taylor Swift, Maren Morris, Dierks Bentley & More on the Legendary Venue". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Spanos, Brittany (July 1, 2019). "Taylor Swift vs. Scooter Braun and Scott Borchetta: What the Hell Happened?". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Rosseinsky, Katie (November 15, 2021). "How Taylor Swift is changing the music industry a re-record at a time". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "About/FAQs". Big Machine Label Group. March 2018. Archived from the original on May 29, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Newman, Melinda (July 2, 2019). "Taylor Swift's Attorney Says Singer Never Had a Chance to 'Outright' Buy Back Her Masters From Big Machine". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Willman, Chris (August 27, 2018). "Taylor Swift Stands to Make Music Business History as a Free Agent". Variety. Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Freeman, Abigail. "Taylor Swift Is 'Free' Again, But Just How Much Is Her 'Fearless' Strategy Worth?". Forbes. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Ingham, Tim (June 30, 2019). "Big Machine Label Group (and its Taylor Swift albums) acquired by Scooter Braun's Ithaca Holdings". Music Business Worldwide. Archived from the original on June 14, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ Acevedo, Angélica. "Talent manager Scooter Braun is in a very public feud with Taylor Swift. Here are 29 of his biggest clients". Insider Inc. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Christman, Ed (June 30, 2019). "Scooter Braun Acquires Scott Borchetta's Big Machine Label Group, Taylor Swift Catalog For Over $300 Million". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Sisario, Ben; Coscarelli, Joe; Kelly, Kate (November 17, 2020). "Taylor Swift Denounces Scooter Braun as Her Catalog Is Sold Again". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ Cranley, Ellen (June 30, 2019). "Taylor Swift said she's 'sad and grossed out' that 'bully' Scooter Braun now owns all of her past music". Insider Inc. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ "Justin Bieber Asks 'Taylor Swift What Up' in Pic With Kanye West". Billboard. August 2, 2016. Archived from the original on February 4, 2022. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c Cullins, Ashley (July 2, 2019). ""She Has No Legal Recourse": Why Taylor Swift Won't Sue Scooter Braun to Get Her Masters". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Sisario, Ben; Coscarelli, Joe (July 1, 2019). "Taylor Swift's Feud With Scooter Braun Spotlights Musicians' Struggles to Own Their Work". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ "Taylor Swift, Scooter Braun feud ramps up as texts leak and stars take sides". The New Zealand Herald. July 2, 2019. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ Aniftos, Rania (November 14, 2019). "Taylor Swift Says Scooter Braun & Scott Borchetta Won't Let Her Perform Her Old Songs at 2019 AMAs". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Bhattacharjee, Riya; Cosgrove, Elly; Mitra, Mallika (November 15, 2019). "Taylor Swift accuses Scott Borchetta and Scooter Braun of 'tyrannical control,' blocking her from performing her old music at AMA". CNBC. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ Cirisano, Tatiana (November 18, 2019). "Taylor Swift Cleared by Big Machine to Perform Old Songs at AMAs". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ The Cut. Archivedfrom the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ Gawley, Paige (November 16, 2020). "Taylor Swift vs. Scooter Braun: A Timeline of Their Big Machine Feud". Entertainment Tonight. Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "AMA 2019: 'Artist of the Decade' Taylor Swift performs career's best songs". WION. November 25, 2019. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ a b "American Music Awards 2019: Taylor Swift takes artist of the decade in record-breaking haul". The Guardian. November 25, 2019. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Henderson, Cydney (April 23, 2020). "Taylor Swift Slams Big Machine's New Unauthorized Live Album as 'Shameless Greed'". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 24, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ Freidman, Rogan (April 27, 2020). "Taylor Swift 2008 Live Album, Which the Singer Protested, is A Bust with Just 33 Copies Streamed So Far". Showbiz411. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ Ramli, Sofiana (July 11, 2019). "Big Machine to re-release Taylor Swift's early singles on limited-edition vinyl". NME. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Taylor Swift's former record label draws criticism for repackaging her catalog". Los Angeles Times. July 10, 2019. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ Komonibo, Ineye. "Making Sense of the Flying Accusations Between Taylor Swift, Scooter Braun, & Big Machine Records". Refinery29. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ "Taylor Swift's 'Love Story (Taylor's Version)' Debuts at No. 1 on Hot Country Songs Chart: 'I'm So Grateful to the Fans'". Billboard. February 22, 2021. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ "Taylor Swift wants to re-record her old hits after ownership row". BBC. August 22, 2019. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ America, Good Morning. "Taylor Swift will re-record her old music next year after ownership dispute". Good Morning America. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Halperin, Shirley (November 16, 2020). "Scooter Braun Sells Taylor Swift's Big Machine Masters for Big Pay Day". Variety. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Greg (September 28, 2005). "Roy Disney-Led Fund Buys 80% of Harlem Globetrotters". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 21, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Knopper, Steve (August 17, 2022). "How a Kid Flick Got Taylor Swift to Remake a Previously Off-Limits Song". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 18, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ^ Beumont-Thomas, Ben (November 17, 2020). "Taylor Swift criticises Scooter Braun after $300m masters sale". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Henini, Janine (March 16, 2022). "Women Changing the Music Industry Today: 'I Deserve the Spotlight'". People. Archived from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ^ Hirwani, Peoni (September 21, 2021). "Taylor Swift's Wildest Dreams could overthrow the original version on UK chart". The Independent. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ Willman, Chris (November 16, 2020). "Taylor Swift Confirms Sale of Her Masters, Says She Is Already Re-Recording Her Catalog". Variety. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Ingham, Tim (June 14, 2023). "Reliving the Taylor Swift catalog sale saga (and following the money ...)". Music Business Worldwide. Archived from the original on June 14, 2023. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Battan, Carrie (April 12, 2021). "Taylor Swift Wins with "Fearless (Taylor's Version)"". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ Savage, Mark (February 12, 2021). "Taylor Swift's two versions Love Story compared". BBC. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Taylor Swift wisely chooses not to rewrite history on Fearless (Taylor's Version) – review". The Independent. April 9, 2021. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Bernstein, Jonathan (April 9, 2021). "Taylor Swift Carefully Reimagines Her Past on 'Fearless: Taylor's Version'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ "Taylor Swift: Fearless (Taylor's Version) review – old wounds take on new resonances | Alexis Petridis' album of the week". the Guardian. April 9, 2021. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Legatspi, Althea (September 17, 2021). "Taylor Swift Surprise-Releases 'Wildest Dreams (Taylor's Version)' for Avid TikTokers". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ Willman, Chris (September 17, 2021). "Taylor Swift's 'Wildest Dreams (Taylor's Version)' Quickly Beats the Original Song's Spotify Record for Single-Day Plays". Variety. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ Willman, Chris (September 17, 2021). "Taylor Swift's 'Wildest Dreams (Taylor's Version)' Quickly Beats the Original Song's Spotify Record for Single-Day Plays". Variety. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ Lipshutz, Jason (June 18, 2021). "Taylor Swift Bumps Up Release of 'Red (Taylors Version)' by a Week". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Iasimone, Ashley (November 14, 2021). "Taylor Swift Breaks Spotify Single-Day Streaming Records With 'Red (Taylor's Version)'". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 15, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (November 21, 2021). "Taylor Swift Scores 10th No. 1 Album on Billboard 200 Chart With 'Red (Taylor's Version)'". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ Khan, Fawzi (November 13, 2021). "10 Songs From Red (Taylor's Version) That Are Better Than The Original". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ Red (Taylor's Version) by Taylor Swift, archived from the original on November 13, 2021, retrieved December 1, 2021

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ "Taylor Swift's 10-minute 'All Too Well' is longest song to reach No.1". Guinness World Records. November 26, 2021. Archived from the original on November 29, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ Richards, Will (December 21, 2021). "Jack Antonoff: 'All Too Well' teaches artists to "not listen" to industry". Rolling Stone UK. Archived from the original on December 23, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Willman, Chris (May 5, 2022). "Taylor Swift Debuts 'This Love (Taylor's Version),' From '1989' Redo, in Amazon's 'The Summer I Turned Pretty' Trailer". Variety. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Strauss, Matthew; Arcand, Rob (September 24, 2022). "Taylor Swift Turns Down Offer to Play 2023 Super Bowl Halftime Show". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ MacCary, Julia (March 16, 2023). "Taylor Swift Is Dropping Four Unreleased Songs Ahead of Her Eras Tour Start". Variety. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ Bernabe, Angeline Jane (May 5, 2023). "Taylor Swift announces 'Speak Now (Taylor's Version)'". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on May 6, 2023. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ @Spotify (July 8, 2023). "We've had the time of our lives breaking records with you 💜 @taylorswift13" (Tweet). Retrieved July 9, 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (July 16, 2023). "Taylor Swift's Re-Recorded 'Speak Now' Debuts at No. 1 on Billboard 200 With 2023's Biggest Week". Billboard. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Carl (July 14, 2023). "Taylor Swift secures 10th Number 1 album with Speak Now (Taylor's Version)". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on July 14, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ Grow, Kory; Mier, Tomás (August 10, 2023). "Shake It Off Again: Taylor Swift's '1989 (Taylor's Version)' Is Finally on the Way". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Ingham, Tim (November 6, 2023). "Taylor Swift's 1989 (Taylor's Version) attracted 1,329% more streams than the original version of 1989 in the US last week". Music Business Worldwide. Archived from the original on November 17, 2023. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ Trust, Gary (November 6, 2023). "Taylor Swift Makes History With Top 6 Songs, All From 1989 (Taylor's Version), on Billboard Global 200 Chart". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (November 1, 2023). "Taylor Swift's 1989 (Taylor's Version) Has Sold Over 1 Million Albums in the U.S." Billboard. Archived from the original on October 28, 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2023.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (November 2, 2023). "Taylor Swift's 1989 (Taylor's Version) Breaks Modern-Era Single-Week Vinyl Sales Record". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 28, 2023. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (November 5, 2023). "Taylor Swift's 1989 (Taylor's Version) Debuts at No. 1 on Billboard 200 With Biggest Week in Nearly a Decade". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 5, 2023. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ Zellner, Xander (November 6, 2023). "Taylor Swift Charts All 21 Songs From 1989 (Taylor's Version) on the Hot 100". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ Nicolaou, Anna (November 11, 2021). "Taylor Swift's battle to shake off the suits". Financial Times. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ "Selena Gomez And Taylor Swift's Friendship Timeline: How Long Have They Been BFFs?". CapitalFM. June 11, 2021. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ Silman, Anna (March 1, 2022). "The many faces of Scooter Braun". Business Insider. Archived from the original on March 1, 2022. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ^ Frater, Patrick; Halperin, Shirley (April 2, 2021). "BTS Label Owner HYBE Merges With Scooter Braun's Ithaca Holdings for $1 Billion (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Archived from the original on October 1, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Mier, Tomás (September 30, 2022). "Scooter Braun Claims He 'Regrets' the Way Taylor Swift Deal Was Handled: I 'Learned an Important Lesson'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 1, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Aswad, Jem (September 30, 2022). "Scooter Braun Says He 'Regrets' the Way Taylor Swift Catalog Acquisition Was Handled". Variety. Archived from the original on September 30, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Sources on the dispute's media attention

- "2021 was another difficult year. These 100 things made USA TODAY's entertainment team happy". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 27, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- Niemietz, Brian. "Top newsmakers of 2021 included leaders, losers, killers, entertainers and a GOAT". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- Scottie Andrew and Leah Asmelash (December 29, 2021). "The pop culture moments of 2021 we couldn't forget if we tried". CNN. Archived from the original on December 29, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- "The 10 best pop-culture moments of 2021". Vogue. December 15, 2021. Archived from the original on December 29, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- Ruggieri, Melissa (December 29, 2021). "Ye's 'Donda' rollout, Adele's triumphant return and more of 2021's biggest music moments". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 29, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- "How Taylor Swift reclaimed 2012 to win 2021". Los Angeles Times. December 17, 2021. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Seemayer, Zach (November 14, 2019). "#IStandWithTaylor: Twitter and Celebs React to Taylor Swift's Music Battle With Scooter Braun". Entertainment Tonight. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ "Dionne Warwick Doubles Down on Paying Postage for Taylor Swift's Scarf". Entertainment Tonight. December 2021. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- Saltwire Network. Archivedfrom the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Rosa, Christopher (July 1, 2019). "Every Celebrity Connected to the Taylor Swift–Scooter Braun Drama". Glamour. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Woodward, Ellie. "Here Are All The Celebs Who've Spoken Out in Support Of Taylor Swift After She Exposed Scott Borchetta And Scooter Braun Again". BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ Peppin, Hayley. "Stars including Selena Gomez and Gigi Hadid have come out in support of Taylor Swift after she accused Scooter Braun and Scott Borchetta of blocking her from performing old songs". Insider Inc. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c Huff, Lauren (July 2, 2019). "Taylor Swift vs. Scooter Braun: Who's on whose side?". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ Sanchez, Chelsey (November 15, 2019). "Gigi Hadid, Selena Gomez, and More Support Taylor Swift Amid Music Battle". Harper's Bazaar. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Rowley, Glenn (November 15, 2019). "Camila Cabello, Gigi Hadid, Selena Gomez & More Celebs Support Taylor Swift in Scooter/Scott Dispute". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ Chan, Anna (September 5, 2021). "Taylor Swift Celebrates Anita Baker Getting Her Masters Back: 'What a Beautiful Moment'". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "Sky Ferreira Expresses Support for Taylor Swift Amid Scooter Braun's Acquisition of Swift's Masters". Paste. July 1, 2019. Archived from the original on April 19, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ White, Adam (April 10, 2021). "Taylor Swift fans bombard Kelly Clarkson with praise over unearthed 're-record albums' tweet". The Independent. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ Smith, Mariah (July 1, 2019). "Taylor Swift, Scooter Braun and the Power of the Unfollow". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ Twersky, Carolyn (July 7, 2019). "Billie Eilish, Harry Styles and More Celebrities Have Unfollowed Scooter Braun Following Taylor Swift Drama". Seventeen. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ Halperin, Shirley (May 11, 2019). "Demi Lovato Signs With Scooter Braun for Management". Variety. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Nyren, Erin (November 16, 2019). "Elizabeth Warren Backs Taylor Swift in Big Machine Battle, Slams Private Equity Firms". Variety. Archived from the original on February 4, 2022. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Frias, Lauren. "AOC defends singer Taylor Swift and condemns private equity firms". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 4, 2022. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Paviour, Ben; Squires, Acacia (October 5, 2021). "How Taylor Swift and her master recordings play into the Virginia race for governor". NPR. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Why Taylor Swift's Masters Are Playing a Role in Virginia Race for Governor". Billboard. October 6, 2021. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Polis sings Taylor Swift song at 'State of the State' address in Denver". Outtherecolorado.com. January 14, 2022. Archived from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ "The 7 biggest lines from Gov. Jared Polis' 2022 State of the State address – and why they're so notable". The Colorado Sun. January 13, 2022. Archived from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Sodomsky, Sam (July 1, 2019). "Taylor Swift's Music Ownership Controversy With Scooter Braun: What It Means and Why It Matters". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Rushe, Dominic (November 23, 2019). "Why Taylor Swift and Scooter Braun's bad blood may reshape the industry". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ "The 50 Most Important Music Moments of the Decade". Rolling Stone. November 25, 2019. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "Taylor Swift sics fans on Scooter Braun, The Carlyle Group". The A. V. Club. November 15, 2019. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Jagannathan, Meera. "Taylor Swift is squaring off with private-equity giant Carlyle Group – here's how the combatants stack up". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Willman, Chris (April 20, 2021). "Taylor Swift's 'Fearless (Taylor's Version)' Debuts Huge: What It Means for Replicating Oldies, Weaponizing Fans". Variety. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ Kornhaber, Spencer (November 14, 2021). "On 'SNL,' Taylor Swift Stopped Time". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ Khan, Fawzia (June 18, 2021). "The Might Of Taylor Swift". Elle. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ Richards, Charlotte (July 14, 2021). "How Taylor Swift can help clients understand dangerous investing". Money Marketing. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "Red (Taylor's version) review: Why Red is Taylor Swift's magnum opus". NZ Herald. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Towey, Hannah (November 16, 2021). "Taylor Swift's rerecorded 'Red' album broke 2 Spotify records in 1 day – here's why it's a big deal for the music industry". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 12, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Gilligan, Eilish. "Taylor Swift's Re-Recordings Expose The Music Industry's Chokehold On Intellectual Property". Refinery29. Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Dwyer, Kate (April 14, 2021). "Why 'Fearless (Taylor's Version)' Hits Different in 2021". Marie Claire. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Sumanac-Johnson, Deana (July 5, 2019). "Masters matter: Taylor Swift's feud shows why ownership can be crucial to musicians". CBC News. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ Jeffries-Chung, James (December 23, 2020). "Canada: Stuff Of Folklore: The Sale Of Taylor Swift's Masters". Mondaq. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Rosene, Peter J. (December 13, 2021). "Taylor Swift Knows Perils of Music Copyright Law "All Too Well"". McBrayer. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Tilghman, Justin. "Exposing the "Folklore" of Re-Recording Clauses (Taylor's Version)". Journal of Intellectual Property. 29 – via HeinOnline.

- ^ Lalwani, Sonal (February 27, 2021). "Taylor Swift and Her "Love Story" With IPR". IIPRD. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Mac Ardle, Aoife Mac; McMahon, Doug (April 20, 2021). "Copyright Issues (Taylor's Version): Who Owns Intellectual Property in Music?". Lexology.com. McCann Fitzgerald. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "Taylor Swift Blasts Scooter Braun During Billboard Woman of the Decade Speech". Pitchfork. December 13, 2019. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Lipshutz, Jason (December 16, 2021). "Billboard's Greatest Pop Stars of 2021: No. 1 – Taylor Swift". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 16, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ "8 Trends That Defined Pop in 2021". GRAMMY.com. December 29, 2021. Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ "2021, in 6 minutes". Vox. December 29, 2021. Archived from the original on December 29, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Greene, Andy (November 28, 2022). "The 50 Worst Decisions in Music History". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 29, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ Browne, David (January 18, 2023). "Remaking Your Old Songs Used to Be Considered Lazy, Shady, and So Uncool. What Changed?". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 19, 2023. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ "8 Trends That Defined Pop in 2021". Grammy Awards. December 29, 2021. Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ Hagy, Paige (September 26, 2023). "The NFL may have wanted Taylor Swift for the Super Bowl halftime show. What they got instead was even better". Fortune. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Dailey, Hannah (July 11, 2023). "U.S. Government Debuts 'Speak Now (FBI's Version)' Encouraging Taylor Swift Fans to Report Crimes". Billboard. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ "Taylor Swift Is Halfway Through Her Rerecording Project. It's Paid Off Big Time". Time. July 6, 2023. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (April 18, 2021). "Taylor Swift's Re-Recorded 'Fearless' Album Debuts at No. 1 on Billboard 200 Chart With Year's Biggest Week". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (October 25, 2023). "Taylor Swift's '1989' May Be Her Biggest Rerecording Yet. Here's Why". The New York Times. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- ^ Peoples, Glenn (November 7, 2023). "Taylor Swift's Original '1989' Dropped 44% in Sales & Streams the Week 'Taylor's Version' Was Released". Billboard. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ Pendleton, Devon; Ballentine, Claire; Patino, Marie; Whiteaker, Chloe; Li, Diana (October 26, 2023). "Taylor Swift Vaults Into Billionaire Ranks With Blockbuster Eras Tour". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on October 26, 2023. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ "BTS named Global Recording Artist of the Year by IFPI for second straight year". Music Business Worldwide. February 24, 2022. Archived from the original on February 24, 2022. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ Voytko, Lisette. "The Highest-Paid Entertainers 2022". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "Kylie Jenner, Taylor Swift And The Other Richest Self-Made Women Under 40". Forbes. June 14, 2022. Archived from the original on June 14, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Nine of the 10 Highest-Paid Musicians of 2021 Were Men". Rolling Stone. January 14, 2022. Archived from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ Christman, Ed (December 29, 2022). "Music's Top Global Money Makers of 2021". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 30, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Willman, Chris (May 25, 2020). "Taylor Swift's (Apparent) Remake of 'Look What You Made Me Do' with Brother Austin Fires Up Fandom". Variety. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Monroe, Jazz (May 25, 2020). "Taylor Swift and Jack Antonoff Team for Mysterious "Look What You Made Me Do" Cover on Killing Eve". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Sakzewski, Emily (May 26, 2020). "What Taylor Swift's mysterious Killing Eve cover could mean in her feud with Scooter Braun". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Richards, Will (May 25, 2020). "Taylor Swift fans think new 'Killing Eve' cover is her getting back at Scooter Braun". NME. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Fernández, Alexia (March 12, 2021). "Spirit Untamed First Look! Hear Taylor Swift's Re-Recorded 'Wildest Dreams (Taylor's Version)' in Trailer". People. Archived from the original on March 12, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ Thao, Phillipe (September 19, 2022). "How 'Fate: The Winx Saga' Scored Season 2's Massive Needle Drops". Netflix. Netflix. Archived from the original on September 30, 2022. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ Woerner, Meredith (June 30, 2023). "'The Summer I Turned Pretty' Trailer Previews Taylor Swift's 'Back to December (Taylor's Version)'". Variety. Archived from the original on July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ "Dwayne Johnson confirms "Bad Blood (Taylor's Version)" will be in DC League of Super-Pets film". The Line of Best Fit. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ a b "Taylor Swift fans share tips on how to make old 'Fearless' album disappear". The Independent. April 9, 2021. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ Kornhaber, Spencer (November 18, 2019). "Taylor Swift Is Waging Reputational Warfare". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ Bowenbank, Starr (April 29, 2022). "Scooter Braun Talks Taylor Swift Re-Recording Music, Says He Disagrees With Artists 'Weaponizing a Fanbase'". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ Nelson, Jeff (July 1, 2019). "Scooter Braun Deletes Friend's Post About Buying Taylor Swift Following Her Bullying Accusations". People. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Calvario, Liz (November 15, 2019). "Big Machine Employees Receive Death Threats Amid Taylor Swift Feud". Entertainment Tonight. Archived from the original on February 12, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Brandle, Lars (November 14, 2019). "Taylor Swift Fans Launch Online Petition Against Scooter Braun, Scott Borchetta". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 10, 2022. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ^ Willman, Chris (April 8, 2021). "Taylor Swift Fans Share Notes on How to Make the Old 'Fearless' Disappear". Variety. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ Dailey, Hannah (May 13, 2022). "Jimmy Fallon Excitedly Dissects Clues to Decipher Which Album Taylor Swift Will Release Next: Watch". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Ahlgrim, Callie (May 8, 2021). "Olivia Rodrigo has full control of her masters because she paid attention to Taylor Swift's battle over her own music". Insider Inc. Archived from the original on November 15, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "Rita Ora inspired by Prince to take control". The Independent. Archived from the original on February 26, 2023. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- PEOPLE.com. Archivedfrom the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ Brodksy, Rachel (March 11, 2022). "We've Got A File On You: Bryan Adams". Stereogum. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ Dearmore, Kelly (March 9, 2022). "Cody Canada Takes Ownership of His Art and Musical Past Thanks to Taylor Swift". Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ Dupre, Elyse (October 10, 2023). "98 Degrees Reveals How Taylor Swift Inspired Them to Re-Record Their Masters". E!. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ "Dave Grohl Is Impressed With Taylor Swift's Re-Recorded Albums". UPROXX. September 14, 2021. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ "Snoop Dogg says he has considered re-recording his albums like Taylor Swift". NME. April 22, 2022. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ "Ashanti says Taylor Swift helped her feel 'empowered' in her decision to re-record debut album". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ Niki Zefanya [@nikizefanya] (May 31, 2022). ""Nicole" – my sophomore album – out this August" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ June, Sophia (December 30, 2022). "Paris Hilton Dropped A New Version Of Her 2006 Hit "Stars Are Blind"". Nylon. Archived from the original on December 30, 2022. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- ^ Mamo, Heran (February 22, 2023). "Billboard Woman of the Year SZA on Making Chart History and Preparing to 'Pop Ass and Cry and Give Theater' On Tour". Billboard. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ "Offset is the Taylor Swift of rap". Yahoo! News. April 4, 2023. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ "Little Women stars compare Taylor Swift to Louisa May Alcott". The Irish News. December 23, 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ Jenkins, Sally (September 28, 2023). "You thought you knew the NFL. Now meet Taylor's Version". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ Iasimone, Ashley (October 28, 2023). "Imogen Heap Shares Photos From 'Clean' Recording Session to Celebrate '1989 (Taylor's Version)' Release". Billboard. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ Woerner, Meredith (December 2, 2023). "Maren Morris Praises 'Brave' Taylor Swift, Sinéad O'Connor and Billie Holiday for Dismantling the Status Quo: They Were All Told to 'Shut Up and Sing'". Variety. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Steele, Anne (November 12, 2021). "As Taylor Swift Rerecorded Her 'Red' Album, Universal Reworked Contracts". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ "[NoW] Taylor Swift's Ten-Minute Song". Weverse. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ "You'll Only Hear Taylor Swift's 'Taylor's Version' Albums On iHeartRadio". iHeartRadio. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Knopper, Steve (October 30, 2023). "Labels Want to Prevent 'Taylor's Version'-Like Re-Recordings From Ever Happening Again". Billboard. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ Forde, Eamonn (January 9, 2024). "Taylor-made deals: how artists are following Swift's rights example". The Guardian. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ a b Suskind, Alex. "Taylor Swift broke all her rules with Folklore – and gave herself a much-needed escape". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 12, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Gallagher, Alex (December 9, 2020). "Taylor Swift wrote early 'My Tears Ricochet' lyrics after watching 'Marriage Story'". NME. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (January 7, 2021). "Taylor Swift Drops Deluxe Edition of 'Evermore' on Streaming, With Lyric Videos For Bonus Tracks". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.