Tekle Haymanot

Ethiopians |

|---|

| Part of Oriental Orthodoxy |

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|---|

|

|

Abune Tekle Haymanot (

Early life

Tekle Haymanot was born in Zorare, a district in

During his youth, Shewa was subject to a number of devastating raids by

His father gave Tekle Haymanot their earliest religious instruction; later he was ordained a priest by the Egyptian Bishop Cyril (known as Kirollos in Coptic).

Later career

The first significant event in his life was when Tekle Haymanot, at the age of 30, travelled north to seek further religious education. His journey took him from Selale to

Eventually, Tekle Haymanot left Debre Damo with his followers to return to Shewa. En route, he stopped at the monastery of Iyasus Mo'a, where tradition states he received the full investiture of an Ethiopian monk's habit. The historian Taddesse Tamrat sees in the existing accounts of this act an attempt by later writers to justify the seniority of the monastery in Lake Hayq over the followers of Tekle Haymanot.[7]

Once in Shewa, he introduced the spirit of renewal that Christianity was experiencing in the northern provinces. He settled in the central area between Selale and Grarya, where he founded in 1284 the monastery of Debre Atsbo (renamed in the 15th century

Tekle Haymanot lived for 29 years after the foundation of this monastery, dying in the year before Emperor Wedem Arad did; this would date Tekle Haymanot's death to 1313. He was first buried in the cave where he had originally lived as a hermit; almost 60 years later he was reinterred at Debre Libanos. In the 1950s, Emperor Haile Selassie constructed a new church at Debre Libanos Monastery over the site of the Saint's tomb. It remains a place of pilgrimage and a favored site for burial for many people across Ethiopia.

Later traditions

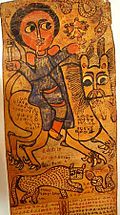

Tekle Haymanot is frequently represented as an old man with wings on his back and only one leg visible. There are a number of explanations for this popular image. C.F. Beckingham and G.W.B. Huntingford recount one story, that the saint "having stood too long for about 34 years, one of his legs broke or cut while Satan was attempting to stop his prayers, whereupon he stood on one foot for 7 years."[8] Paul B. Henze describes his missing leg as appearing as a "severed leg ... in the lower left corner discreetly wrapped in a cloth."[9] The traveller Thomas Pakenham learned from the Prior of Debre Damo how Tekle Haymanot received his wings:

- One day he said he would go to Jerusalem to see the Golgotha. But Shaitan (Satan) planned to stop Tekla Haymanot going on his journey to the Holy Land, and he cut the rope which led from the rock to the ground just as Tekla Haymanot started to climb down. Then God gave Tekla Haymanot six wings and he flew down to the valley below ... and from that day onwards Teklahaimanot would fly back and forth to Jerusalem above the clouds like an aeroplane.[10]

Many traditions hold that Tekle Haymanot played a significant role in Yekuno Amlak's ascension as the restored monarchy of the Solomonic dynasty,[11] following two centuries of rule by the Zagwe dynasty, although historians like Taddesse Tamrat believe these are later inventions. (A few older traditions credit Iyasus Mo'a with this honour.)

Another tradition credits Tekle Haymanot as the only Lek'e P'ap'as of Ethiopia who was born in Ethiopia and who was

A number of

See also

- Coptic Christianity

- Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

- St. Takla Haymanot's Church (Alexandria)

References

- ^ African Languages and Cultures, 10 (1997), p. 184

- ^ Donald N. Levine, Wax and Gold: Tradition and Innovation in Ethiopia Culture (Chicago: University Press, 1972), p. 73

- ^ G.W.B. Huntingford, The Historical Geography of Ethiopia (London: The British Academy, 1989), The Life of Takla Haymanot in the Version of Dabra Libanos and the Miracles of Takla Haymanot in the Version of Dabra Libanos, and the Book of the Riches of Kings. Translated by E. A. Wallis Budge. London 1906.

- ^ G.W.B. Huntingford, The Historical Geography of Ethiopia (London: The British Academy, 1989), p. 69

- ^ The Life of Takla Haymanot in the Version of Dabra Libanos and the Miracles of Takla Haymanot in the Version of Dabra Libanos, and the Book of the Riches of Kings. Translated by E. A. Wallis Budge. London 1906.

- ^ a b Tesfaye Gebre Mariam, "Structural Analysis", p. 188

- ^ Taddasse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (1270-1527) (Oxford, 1972), pp. 160-189

- ^ C.F. Beckingham and G.W.B. Huntingford, trans. The Prester John of the Indies by Alfonso Alvarez, (Cambridge: Hakluyt Society, 1961), p. 394n.

- ^ Paul B. Henze, Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia (New York: Palgrave, 2000), p. 63

- ^ Pakenham, The Mountains of Rasselas (New York: Reynal, 1959), p. 84

- ^ Henze, Layers of Time, p. 62n.50

- ^ E.A. Wallis Budge, A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia, 1928 (Oosterhout, the Netherlands: Anthropological Publications, 1970), p. 286

- ^ The Life of Takla Haymanot in the Version of Dabra Libanos and the Miracles of Takla Haymanot in the Version of Dabra Libanos, and the Book of the Riches of Kings. Translated by E. A. Wallis Budge. London 1906.