Ileum

| Ileum | |

|---|---|

vagus[1] | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ileum |

| MeSH | D007082 |

| TA98 | A05.6.04.001 |

| TA2 | 2959 |

| FMA | 7208 |

| Anatomical terminology] | |

|

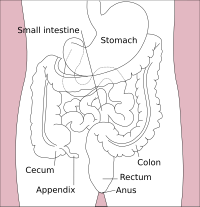

| Major parts of the |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

|---|

The ileum (

The ileum follows the duodenum and jejunum and is separated from the cecum by the ileocecal valve (ICV). In humans, the ileum is about 2–4 m long, and the pH is usually between 7 and 8 (neutral or slightly basic).

Ileum is derived from the Greek word εἰλεός (eileós), referring to a medical condition known as ileus.

Structure

The ileum is the third and final part of the small intestine. It follows the jejunum and ends at the ileocecal junction, where the terminal ileum communicates with the cecum of the large intestine through the ileocecal valve. The ileum, along with the jejunum, is suspended inside the mesentery, a peritoneal formation that carries the blood vessels supplying them (the superior mesenteric artery and vein), lymphatic vessels and nerve fibers.[3]

There is no line of demarcation between the jejunum and the ileum. There are, however, subtle differences between the two:[3]

- The ileum has more fat inside the mesentery than the jejunum.

- The diameter of its lumen is smaller and has thinner walls than the jejunum.

- Its circular folds are smaller and absent in the terminal part of the ileum.

- While the length of the intestinal tract contains lymphoid nodules that contain large numbers of lymphocytes and other cells of the immune system.

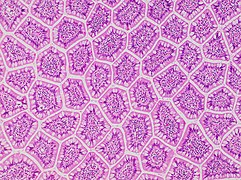

Histology

The four layers that make up the wall of the ileum are consistent with those of the

- A mucous membrane, itself formed by three different layers:

- A single layer of hormones.

- An underlying Peyer's patches, which are a distinctive feature of the ileum.[4]: 589

- A thin layer of smooth muscle called muscularis mucosae

- A single layer of

- A blood vessels and a nervous component called submucosal plexus, which is part of the enteric nervous system

- An external muscular layer formed by two layers of smooth muscle arranged in circular bundles in the inner layer and in longitudinal bundles in the outer layer. Between the two layers is the myenteric plexus, formed by nervous tissue and also a part of the enteric nervous system.

- A serosa composed of mesothelium, a single layer of flat cells with varying quantities of underlying connective and adipose tissue. This layer represents the visceral peritoneum and is continuous with the mesentery.[4]: 571

-

General structure of the gut wall. Brunner's glands are not found in the ileum, but are a distinctive feature of the duodenum.

-

enterocytes are visible over a core of lamina propria.

-

Cross section of ileum with a Peyer's patch circled.

-

Cross-section histology ofintestinal villiof the human terminal ileum.

Development

The

In the fetus the ileum is connected to the navel by the vitelline duct. In roughly 2−4% of humans, this duct fails to close during the first seven weeks after birth, leaving a remnant called Meckel's diverticulum.[7]

Function

The main function of the ileum is to absorb

The villi contain large numbers of capillaries that take the amino acids and glucose produced by digestion to the

Clinical significance

It is of importance in medicine as it can be affected in a number of diseases,[8] including:

- Crohn's disease

- Tuberculosis

- Lymphoma

- Neuroendocrine tumors (carcinoid)

Other animals

In veterinary anatomy, the ileum is distinguished from the jejunum by being that portion of the jejunoileum that is connected to the

The ileum is the short termi of the small intestine and the connection to the large intestine. It is suspended by the caudal part of the mesentery (mesoileum) and is attached, in addition, to the cecum by the ileocecal fold. The ileum terminates at the cecocolic junction of the large intestine forming the ileal orifice. In the dog the ileal orifice is located at the level of the first or second lumbar vertebra, in the ox in the level of the fourth lumbar vertebrae, in the sheep and goat at the level of the caudal point of the costal arch.[9] By active muscular contraction of the ileum, and closure of the ileal opening as a result of engorgement, the ileum prevents the backflow of ingesta and the equalization of pressure between jejunum and the base of the cecum. Disturbance of this sensitive balance is not uncommon and is one of the causes of colic in horses. During any intestinal surgery, for instance, during appendectomy, distal 2 feet of ileum should be checked for the presence of Meckel's diverticulum.

References

- ^ Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 6/6ch2/s6ch2_30". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

- ^

Guillaume, Jean; Praxis Publishing; Sadasivam Kaushik; Pierre Bergot; Robert Metailler (2001). Nutrition and Feeding of Fish and Crustaceans. Springer. p. 31. ISBN 1-85233-241-7. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4511-8447-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-7200-6.

- PMID 21248635.

- ^ ISBN 9780443068119.

- PMID 17021300.

- S2CID 28873753.

- ^ Nickel, R., Shummer, A., Seiferle, E. (1979) The viscera of the domestic mammals, 2nd edn. Springer-Verlag, New York, USA.[page needed]

External links

- Anatomy photo:37:11-0101 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "Abdominal Cavity: The Jejunum and the Ileum"

- Anatomy image:7787 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Anatomy image:8755 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Histology image: 12001oca – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Ileal Villi at endoatlas.com

- Ileum Microscopic Cross Section at nhmccd.edu

- Ileum 20x at deltagen.com