Tests of general relativity

| General relativity |

|---|

|

Tests of general relativity serve to establish observational evidence for the

In the 1970s, scientists began to make additional tests, starting with

In February 2016, the

Classical tests

Albert Einstein proposed[3][4] three tests of general relativity, subsequently called the "classical tests" of general relativity, in 1916:

- the perihelion precession of Mercury's orbit

- the deflection of light by the Sun

- the gravitational redshift of light

In the letter to The Times (of London) on November 28, 1919, he described the theory of relativity and thanked his English colleagues for their understanding and testing of his work. He also mentioned three classical tests with comments:[5]

- "The chief attraction of the theory lies in its logical completeness. If a single one of the conclusions drawn from it proves wrong, it must be given up; to modify it without destroying the whole structure seems to be impossible."

Perihelion precession of Mercury

Under

In general relativity, this remaining

Although earlier measurements of planetary orbits were made using conventional telescopes, more accurate measurements are now made with

| Amount (arcsec/Julian century)[12] | Cause |

|---|---|

| 532.3035 | gravitational tugs of other solar bodies |

| 0.0286 | oblateness of the Sun (quadrupole moment) |

| 42.9799 | gravitoelectric effects (Schwarzschild-like), a general relativity effect |

| −0.0020 | Lense–Thirring precession |

| 575.31[12] | total predicted |

| 574.10 ± 0.65[11] | observed |

The correction by (42.980 ± 0.001)″/cy is the prediction of post-Newtonian theory with parameters .[13] Thus the effect can be fully explained by general relativity. More recent calculations based on more precise measurements have not materially changed the situation.

In general relativity the perihelion shift σ, expressed in radians per revolution, is approximately given by:[14]

where L is the

The other planets experience perihelion shifts as well, but, since they are farther from the Sun and have longer periods, their shifts are lower, and could not be observed accurately until long after Mercury's. For example, the perihelion shift of Earth's orbit due to general relativity is theoretically 3.83868″ per century and experimentally (3.8387 ± 0.0004)″/cy, Venus's is 8.62473″/cy and (8.6247 ± 0.0005)″/cy and Mars' is (1.351 ± 0.001)″/cy. Both values have now been measured, with results in good agreement with theory.

Deflection of light by the Sun

The first observation of light deflection was performed by noting the change in position of

The early accuracy, however, was poor and there was doubt that the small number of measured star locations and instrument questions could produce a reliable result. The results were argued by some

Gravitational redshift of light

Einstein predicted the

The redshift of Sirius B was finally measured by Greenstein et al. in 1971, obtaining the value for the gravitational redshift of 89±16 km/s, with more accurate measurements by the Hubble Space Telescope showing 80.4±4.8 km/s.[38]

Tests of special relativity

The general theory of relativity incorporates Einstein's

Modern tests

The modern era of testing general relativity was ushered in largely at the impetus of

Experimentally, new developments in

Post-Newtonian tests of gravity

Early tests of general relativity were hampered by the lack of viable competitors to the theory: it was not clear what sorts of tests would distinguish it from its competitors. General relativity was the only known relativistic theory of gravity compatible with special relativity and observations. Moreover, it is an extremely simple and elegant theory.[, which parametrizes, in terms of ten adjustable parameters, all the possible departures from Newton's law of universal gravitation to first order in the velocity of moving objects (i.e. to first order in , where v is the velocity of an object and c is the speed of light). This approximation allows the possible deviations from general relativity, for slowly moving objects in weak gravitational fields, to be systematically analyzed. Much effort has been put into constraining the post-Newtonian parameters, and deviations from general relativity are at present severely limited.

The experiments testing gravitational lensing and light time delay limits the same post-Newtonian parameter, the so-called Eddington parameter γ, which is a straightforward parametrization of the amount of deflection of light by a gravitational source. It is equal to one for general relativity, and takes different values in other theories (such as Brans–Dicke theory). It is the best constrained of the ten post-Newtonian parameters, but there are other experiments designed to constrain the others. Precise observations of the perihelion shift of Mercury constrain other parameters, as do tests of the strong equivalence principle.

One of the goals of the BepiColombo mission to Mercury, is to test the general relativity theory by measuring the parameters gamma and beta of the parametrized post-Newtonian formalism with high accuracy.[43][44] The experiment is part of the Mercury Orbiter Radio science Experiment (MORE).[45][46] The spacecraft was launched in October 2018 and is expected to enter orbit around Mercury in December 2025.

Gravitational lensing

One of the most important tests is

The entire sky is slightly distorted due to the gravitational deflection of light caused by the Sun (the anti-Sun direction excepted). This effect has been observed by the European Space Agency astrometric satellite Hipparcos. It measured the positions of about 105 stars. During the full mission about 3.5×106 relative positions have been determined, each to an accuracy of typically 3 milliarcseconds (the accuracy for an 8–9 magnitude star). Since the gravitation deflection perpendicular to the Earth–Sun direction is already 4.07 milliarcseconds, corrections are needed for practically all stars. Without systematic effects, the error in an individual observation of 3 milliarcseconds, could be reduced by the square root of the number of positions, leading to a precision of 0.0016 milliarcseconds. Systematic effects, however, limit the accuracy of the determination to 0.3% (Froeschlé, 1997).

Launched in 2013, the Gaia spacecraft will conduct a census of one billion stars in the Milky Way and measure their positions to an accuracy of 24 microarcseconds. Thus it will also provide stringent new tests of gravitational deflection of light caused by the Sun which was predicted by General relativity.[48]

Light travel time delay testing

More recently, the

Equivalence principle

The equivalence principle, in its simplest form, asserts that the trajectories of falling bodies in a gravitational field should be independent of their mass and internal structure, provided they are small enough not to disturb the environment or be affected by

A version of the equivalence principle, called the

Another part of the strong equivalence principle is the requirement that Newton's gravitational constant be constant in time, and have the same value everywhere in the universe. There are many independent observations limiting the possible variation of Newton's

Gravitational redshift and time dilation

The first of the classical tests discussed above, the

Experimental verification of gravitational redshift using terrestrial sources took several decades, because it is difficult to find clocks (to measure time dilation) or sources of electromagnetic radiation (to measure redshift) with a frequency that is known well enough that the effect can be accurately measured. It was confirmed experimentally for the first time in 1959 using measurements of the change in wavelength of gamma-ray photons generated with the Mössbauer effect, which generates radiation with a very narrow line width. The Pound–Rebka experiment measured the relative redshift of two sources situated at the top and bottom of Harvard University's Jefferson tower.[61][62] The result was in excellent agreement with general relativity. This was one of the first precision experiments testing general relativity. The experiment was later improved to better than the 1% level by Pound and Snider.[63]

The blueshift of a falling photon can be found by assuming it has an equivalent mass based on its frequency E = hf (where h is the Planck constant) along with E = mc2, a result of special relativity. Such simple derivations ignore the fact that in general relativity the experiment compares clock rates, rather than energies. In other words, the "higher energy" of the photon after it falls can be equivalently ascribed to the slower running of clocks deeper in the gravitational potential well. To fully validate general relativity, it is important to also show that the rate of arrival of the photons is greater than the rate at which they are emitted. A very accurate gravitational redshift experiment, which deals with this issue, was performed in 1976,[64] where a hydrogen maser clock on a rocket was launched to a height of 10,000 km, and its rate compared with an identical clock on the ground. It tested the gravitational redshift to 0.007%.

Although the Global Positioning System (GPS) is not designed as a test of fundamental physics, it must account for the gravitational redshift in its timing system, and physicists have analyzed timing data from the GPS to confirm other tests. When the first satellite was launched, some engineers resisted the prediction that a noticeable gravitational time dilation would occur, so the first satellite was launched without the clock adjustment that was later built into subsequent satellites. It showed the predicted shift of 38 microseconds per day. This rate of discrepancy is sufficient to substantially impair function of GPS within hours if not accounted for. An excellent account of the role played by general relativity in the design of GPS can be found in Ashby 2003.[65]

Other precision tests of general relativity,[66] not discussed here, are the Gravity Probe A satellite, launched in 1976, which showed gravity and velocity affect the ability to synchronize the rates of clocks orbiting a central mass and the Hafele–Keating experiment, which used atomic clocks in circumnavigating aircraft to test general relativity and special relativity together.[67][68]

Frame-dragging tests

Tests of the

The Gravity Probe B satellite, launched in 2004 and operated until 2005, detected frame-dragging and the geodetic effect. The experiment used four quartz spheres the size of ping pong balls coated with a superconductor. Data analysis continued through 2011 due to high noise levels and difficulties in modelling the noise accurately so that a useful signal could be found. Principal investigators at Stanford University reported on May 4, 2011, that they had accurately measured the frame dragging effect relative to the distant star IM Pegasi, and the calculations proved to be in line with the prediction of Einstein's theory. The results, published in Physical Review Letters measured the geodetic effect with an error of about 0.2 percent. The results reported the frame dragging effect (caused by Earth's rotation) added up to 37 milliarcseconds with an error of about 19 percent.[73] Investigator Francis Everitt explained that a milliarcsecond "is the width of a human hair seen at the distance of 10 miles".[74]

In January 2012,

Tests of the gravitational potential at small distances

It is possible to test whether the gravitational potential continues with the inverse square law at very small distances. Tests so far have focused on a divergence from GR in the form of a Yukawa potential , but no evidence for a potential of this kind has been found. The Yukawa potential with has been ruled out down to λ = 5.6×10−5 m.[80]

Mössbauer rotor experiment

It was conceived as a means to measure the

Be that as it may, an early 21st Century re-examination of these endeavors called into question the validity of the past obtained results claiming to have verified time dilation as predicted by Einstein's relativity theory,[85][86] whereby novel experimentations were carried out that uncovered an extra energy shift between emitted and absorbed radiation next to the classical relativistic dilation of time.[87][88] This discovery was first explained as discrediting general relativity and successfully confirming at the laboratory scale the predictions of an alternative theory of gravity developed by T. Yarman and his colleagues.[89] Against this development, a contentious attempt was made to explain the disclosed extra energy shift as arising from a so-far unknown and allegedly missed clock synchronization effect,[90][91] which was unusually awarded a prize in 2018 by the Gravity Research Foundation for having secured a new proof of general relativity.[92] However, at the same time period, it was revealed that said author committed several mathematical errors in his calculations,[93] and the supposed contribution of the so-called clock synchronization to the measured time dilation is in fact practically null.[94][95][96][97][98][99] As a consequence, a general relativistic explanation for the outcomes of Mössbauer rotor experiments remains open.

Strong field tests

The very strong gravitational fields that are present close to

Binary pulsars

Similarly to the way in which atoms and molecules emit electromagnetic radiation, a gravitating mass that is in

The radiation of gravitational waves has been inferred from the

A "double pulsar" discovered in 2003,

In 2013, an international team of astronomers reported new data from observing a pulsar-white dwarf system PSR J0348+0432, in which they have been able to measure a change in the orbital period of 8 millionths of a second per year, and confirmed GR predictions in a regime of extreme gravitational fields never probed before;[106] but there are still some competing theories that would agree with these data.[107]

Direct detection of gravitational waves

A number of

General relativity predicts gravitational waves, as does any theory of gravitation in which changes in the gravitational field propagate at a finite speed.[111] Then, the LIGO response function could discriminate among the various theories.[112][113] Since gravitational waves can be directly detected,[1][109] it is possible to use them to learn about the Universe. This is gravitational-wave astronomy. Gravitational-wave astronomy can test general relativity by verifying that the observed waves are of the form predicted (for example, that they only have two transverse polarizations), and by checking that black holes are the objects described by solutions of the Einstein field equations.[114][115][116]

Gravitational-wave astronomy can also test Maxwell-Einstein field equations. This version of the field equations predicts that spinning magnetars (i.e., neutron stars with extremely strong magnetic dipole field) should emit gravitational waves.[117]

"These amazing observations are the confirmation of a lot of theoretical work, including Einstein's general theory of relativity, which predicts gravitational waves", said Stephen Hawking.[1]

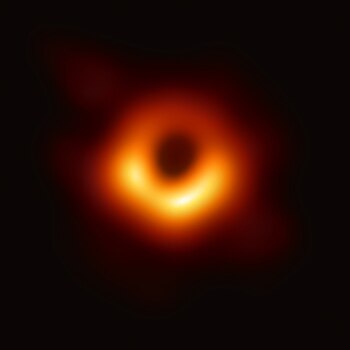

Direct observation of black holes

The galaxy M87 was the subject of observation by the

Gravitational redshift and orbit precession of star in strong gravity field

Gravitational redshift in light from the S2 star orbiting the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* in the center of the Milky Way has been measured with the Very Large Telescope using GRAVITY, NACO and SIFONI instruments.[120][121] Additionally, there has now been detection of the Schwarzschild precession in the orbit of the star S2 near the Galactic centre massive black hole.[122]

Strong equivalence principle

The strong equivalence principle of general relativity requires universality of free fall to apply even to bodies with strong self-gravity. Direct tests of this principle using Solar System bodies are limited by the weak self-gravity of the bodies, and tests using pulsar–white-dwarf binaries have been limited by the weak gravitational pull of the Milky Way. With the discovery of a triple star system called PSR J0337+1715, located about 4,200 light-years from Earth, the strong equivalence principle can be tested with a high accuracy. This system contains a neutron star in a 1.6-day orbit with a white dwarf star, and the pair in a 327-day orbit with another white dwarf further away. This system permits a test that compares how the gravitational pull of the outer white dwarf affects the pulsar, which has strong self-gravity, and the inner white dwarf. The result shows that the accelerations of the pulsar and its nearby white-dwarf companion differ fractionally by no more than 2.6×10−6 (95% confidence level).[123][124][125]

X-ray spectroscopy

This technique is based on the idea that photon trajectories are modified in the presence of a gravitational body. A very common astrophysical system in the universe is a black hole surrounded by an accretion disk. The radiation from the general neighborhood, including the accretion disk, is affected by the nature of the central black hole. Assuming Einstein's theory is correct, astrophysical black holes are described by the Kerr metric. (A consequence of the no-hair theorems.) Thus, by analyzing the radiation from such systems, it is possible to test Einstein's theory.

Most of the radiation from these black hole – accretion disk systems (e.g., black hole binaries and active galactic nuclei) arrives in the form of X-rays. When modeled, the radiation is decomposed into several components. Tests of Einstein's theory are possible with the thermal spectrum (only for black hole binaries) and the reflection spectrum (for both black hole binaries and active galactic nuclei). The former is not expected to provide strong constraints,[126] while the latter is much more promising.[127] In both cases, systematic uncertainties might make such tests more challenging.[128]

Cosmological tests

Tests of general relativity on the largest scales are not nearly so stringent as Solar System tests.

Some other cosmological tests include searches for primordial gravitational waves generated during

In August 2017, the findings of tests conducted by astronomers using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT), among other instruments, were released, and positively demonstrated gravitational effects predicted by Albert Einstein. One of these tests observed the orbit of the stars circling around Sagittarius A*, a black hole about 4 million times as massive as the sun. Einstein's theory suggested that large objects bend the space around them, causing other objects to diverge from the straight lines they would otherwise follow. Although previous studies have validated Einstein's theory, this was the first time his theory had been tested on such a gigantic object. The findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal.[139][140]

Gravitational lensing

Astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope and the Very Large Telescope have made precise tests of general relativity on galactic scales. The nearby galaxy ESO 325-G004 acts as a strong gravitational lens, distorting light from a distant galaxy behind it to create an Einstein ring around its centre. By comparing the mass of ESO 325-G004 (from measurements of the motions of stars inside this galaxy) with the curvature of space around it, astronomers found that gravity behaves as predicted by general relativity on these astronomical length-scales.[141][142]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ S2CID 182916902. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ^ a b Conover, Emily, LIGO snags another set of gravitational waves, Science News, June 1, 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ . Retrieved 2006-09-03.

- .

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1919). "What Is The Theory Of Relativity?" (PDF). German History in Documents and Images. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ "Precession of Mercury's Perihelion" (PDF).

- ^ a b Le Verrier, U. (1859). "Lettre de M. Le Verrier à M. Faye sur la théorie de Mercure et sur le mouvement du périhélie de cette planète". Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences. 49: 379–383.

- ^ Campbell, W. W. (1909). "Report of the Lick Observatory". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 21 (128): 213–214.

- S2CID 121157855.

- ISBN 978-0-306-45567-4.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 125439949.

- ^ http://www.tat.physik.uni-tuebingen.de/~kokkotas/Teaching/Experimental_Gravity_files/Hajime_PPN.pdf Archived 2014-03-22 at the Wayback Machine – Perihelion shift of Mercury, page 11

- S2CID 118620173.

- ISBN 978-0-8493-2891-6.

- Bibcode:2005ASPC..328...25W.

- ^ Naeye, Robert, "Stellar Mystery Solved, Einstein Safe", Sky and Telescope, September 16, 2009. See also MIT Press Release, September 17, 2009. Accessed 8 June 2017.

- ^ Soldner, J. G. V. (1804). . Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch: 161–172.

- arXiv:physics/0508030.

- PMID 28179848. (ArXiv version here: arxiv.org/abs/1403.7377.)

- ^ Ned Wright: Deflection and Delay of Light

- ^ .

- S2CID 25615643.

- ^ Rosenthal-Schneider, Ilse: Reality and Scientific Truth. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1980. p 74. See also Calaprice, Alice: The New Quotable Einstein. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005. p 227.

- ISBN 0-521-47736-0

- S2CID 119203172.

- S2CID 120524925.

- ^ a b D. Kennefick, "Testing relativity from the 1919 eclipse- a question of bias", Physics Today, March 2009, pp. 37–42.

- ^ Barker, Geoff (22 August 2012). "Einstein's Theory of Relativity Proven in Australia, 1922". Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ van Biesbroeck, G.: The relativity shift at the 1952 February 25 eclipse of the Sun., Astronomical Journal, vol. 58, page 87, 1953.

- ^ Texas Mauritanian Eclipse Team: Gravitational deflection of-light: solar eclipse of 30 June 1973 I. Description of procedures and final results., Astronomical Journal, vol. 81, page 452, 1976.

- S2CID 1385516.

- ISBN 978-5-9651-0873-2.

- S2CID 206654918.

- ^ Hetherington, N. S., "Sirius B and the gravitational redshift – an historical review", Quarterly Journal Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 21, Sept. 1980, p. 246-252. Accessed 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b Holberg, J. B., "Sirius B and the Measurement of the Gravitational Redshift", Journal for the History of Astronomy, Vol. 41, 1, 2010, p. 41-64. Accessed 6 April 2017.

- ^ Effective Temperature, Radius, and Gravitational Redshift of Sirius B, J. L. Greenstein, J.B. Oke, H. L. Shipman, Astrophysical Journal 169 (Nov. 1, 1971), pp. 563–566.

- PMID 17735811.

- ^ Dicke, R. H. (1962). "Mach's Principle and Equivalence". Evidence for gravitational theories: proceedings of course 20 of the International School of Physics "Enrico Fermi" ed C. Møller.

- .

- .

- ^ "Fact Sheet".

- .

- hdl:11568/804045.

- ^ The Mercury Orbiter Radio Science Experiment (MORE) on board the ESA/JAXA BepiColombo MIssion to Mercury. SERRA, DANIELE; TOMMEI, GIACOMO; MILANI COMPARETTI, ANDREA. Università di Pisa, 2017.

- S2CID 4506243.

- ^ esa. "Gaia overview".

- .

- .

- S2CID 4337125.

- S2CID 18890863.

- S2CID 10506077.

- S2CID 14002701.

- S2CID 15412146.

- S2CID 9146534.

- .

- .

- S2CID 119358769.

- S2CID 118684485.

- .

- .

- .

- .

- PMID 28163638.

- ^ "Gravitational Physics with Optical Clocks in Space" (PDF). S. Schiller (PDF). Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf. 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- S2CID 10067969.

- S2CID 37376002.

- S2CID 4423434.

- S2CID 12238950.

- S2CID 118646069.

- S2CID 11685632.

- S2CID 11878715.

- ^ Ker Than (2011-05-05). "Einstein Theories Confirmed by NASA Gravity Probe". News.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ "Prepping satellite to test Albert Einstein".

- ^

Ciufolini, I.; et al. (2009). "Towards a One Percent Measurement of Frame Dragging by Spin with Satellite Laser Ranging to LAGEOS, LAGEOS 2 and LARES and GRACE Gravity Models". S2CID 120442993.

- ^

Ciufolini, I.; Paolozzi A.; Pavlis E. C.; Ries J. C.; Koenig R.; Matzner R. A.; Sindoni G. & Neumayer H. (2009). "Towards a One Percent Measurement of Frame Dragging by Spin with Satellite Laser Ranging to LAGEOS, LAGEOS 2 and LARES and GRACE Gravity Models". S2CID 120442993.

- ^

Ciufolini, I.; Paolozzi A.; Pavlis E. C.; Ries J. C.; Koenig R.; Matzner R. A.; Sindoni G. & Neumayer H. (2010). "Gravitomagnetism and Its Measurement with Laser Ranging to the LAGEOS Satellites and GRACE Earth Gravity Models". General Relativity and John Archibald Wheeler. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Vol. 367. SpringerLink. pp. 371–434. ISBN 978-90-481-3734-3.

- ^

Paolozzi, A.; Ciufolini I.; Vendittozzi C. (2011). "Engineering and scientific aspects of LARES satellite". Acta Astronautica. 69 (3–4): 127–134. ISSN 0094-5765.

- S2CID 16379220.

- S2CID 250837656.

- .

- ISSN 0370-1328.

- .

- S2CID 30608323.

- S2CID 121546571.

- .

- S2CID 117936697.

- S2CID 120671970.

- S2CID 119248058.

- S2CID 55583610.

- S2CID 56302187.

- S2CID 145981014.

- .

- S2CID 124589281.

- .

- S2CID 105930092.

- S2CID 149746550.

- S2CID 149746550.

- ^ In general relativity, a perfectly spherical star (in vacuum) that expands or contracts while remaining perfectly spherical cannot emit any gravitational waves (similar to the lack of e/m radiation from a pulsating charge), as Birkhoff's theorem says that the geometry remains the same exterior to the star. More generally, a rotating system will only emit gravitational waves if it lacks the axial symmetry with respect to the axis of rotation.

- PMID 28163640.

- .

- S2CID 118573183.

- ^ "Press Release: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1993". Nobel Prize. 13 October 1993. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- S2CID 6674714.

- S2CID 15221098.

- S2CID 123752543. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- S2CID 124959784.

- ^ a b "Gravitational waves detected 100 years after Einstein's prediction | NSF - National Science Foundation". www.nsf.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (16 October 2017). "Gravitational Waves Detected from Neutron-Star Crashes: The Discovery Explained". Space.com. Purch. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- .

- )

- S2CID 721314.

- PMID 28163624.

- PMID 28179845.

- S2CID 217275338.

- S2CID 16723637.

- ^ S2CID 145906806.

- ^ "Focus on the First Event Horizon Telescope Results". Shep Doeleman. The Astrophysical Journal. 10 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "First Successful Test of Einstein's General Relativity Near Supermassive Black Hole". Hämmerle, Hannelore. Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics. 26 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- S2CID 118891445.

- S2CID 215768928.

- S2CID 49578025.

- ^ "Even Phenomenally Dense Neutron Stars Fall like a Feather - Einstein Gets It Right Again". Charles Blue, Paul Vosteen. NRAO. 4 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- S2CID 218486794.

- S2CID 119280889.

- S2CID 118397255.

- S2CID 119372075.

- S2CID 1700265.

- ^ a b Rudnicki, 1991, p. 28. The Hubble Law was viewed by many as an observational confirmation of General Relativity in the early years

- ^ a b c d W.Pauli, 1958, pp. 219–220

- ^ Kragh, 2003, p. 152

- ^ a b Kragh, 2003, p. 153

- ^ Rudnicki, 1991, p. 28

- ^ Chandrasekhar, 1980, p. 37

- PMID 19370005.

- S2CID 205219902.

- S2CID 4403989.

- ^ Patel, Neel V. (9 August 2017). "The Milky Way's Supermassive Black Hole is Proving Einstein Correct". Inverse via Yahoo.news. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ Duffy, Sean (10 August 2017). "Black Hole Indicates Einstein Was Right: Gravity Bends Space". Courthouse News Service. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ "Einstein proved right in another galaxy". Press Office. University of Portsmouth. 22 June 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- S2CID 49363216.

Other research papers

- Bertotti, B.; Iess, L.; Tortora, P. (2003). "A test of general relativity using radio links with the Cassini spacecraft". Nature. 425 (6956): 374–6. S2CID 4337125.

- Kopeikin, S.; Polnarev, A.; Schaefer, G.; Vlasov, I. (2007). "Gravimagnetic effect of the barycentric motion of the Sun and determination of the post-Newtonian parameter γ in the Cassini experiment". Physics Letters A. 367 (4–5): 276–280. S2CID 18890863.

- Brans, C.; Dicke, R. H. (1961). "Mach's principle and a relativistic theory of gravitation". Phys. Rev. 124 (3): 925–35. .

- A. Einstein, "Über das Relativitätsprinzip und die aus demselben gezogene Folgerungen", Jahrbuch der Radioaktivitaet und Elektronik 4 (1907); translated "On the relativity principle and the conclusions drawn from it", in The collected papers of Albert Einstein. Vol. 2 : The Swiss years: writings, 1900–1909 (Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1989), Anna Beck translator. Einstein proposes the gravitational redshift of light in this paper, discussed online at The Genesis of General Relativity.

- A. Einstein, "Über den Einfluß der Schwerkraft auf die Ausbreitung des Lichtes", Annalen der Physik 35 (1911); translated "On the Influence of Gravitation on the Propagation of Light" in The collected papers of Albert Einstein. Vol. 3 : The Swiss years: writings, 1909–1911 (Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1994), Anna Beck translator, and in The Principle of Relativity, (Dover, 1924), pp 99–108, W. Perrett and G. B. Jeffery translators, ISBN 0-486-60081-5. The deflection of light by the sun is predicted from the principle of equivalence. Einstein's result is half the full value found using the general theory of relativity.

- Shapiro, S. S.; Davis, J. L.; Lebach, D. E.; Gregory J.S. (26 March 2004). "Measurement of the solar gravitational deflection of radio waves using geodetic very-long-baseline interferometry data, 1979–1999". Physical Review Letters. 92 (121101): 121101. PMID 15089661.

- M. Froeschlé, F. Mignard and F. Arenou, "Determination of the PPN parameter γ with the Hipparcos data" Hipparcos Venice '97, ESA-SP-402 (1997).

- Will, Clifford M. (2006). "Was Einstein Right? Testing Relativity at the Centenary". Annalen der Physik. 15 (1–2): 19–33. S2CID 117829175.

- Rudnicki, Conrad (1991). "What are the Empirical Bases of the Hubble Law" (PDF). Apeiron (9–10): 27–36. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- Chandrasekhar, S. (1980). "The Role of General Relativity in Astronomy: Retrospect and Prospect" (PDF). J. Astrophys. Astron. 1 (1): 33–45. S2CID 125915338. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- Kragh, Helge; Smith, Robert W. (2003). "Who discovered the expanding universe". History of Science. 41 (2): 141–62. S2CID 119368912.

Textbooks

- S. M. Carroll, Spacetime and Geometry: an Introduction to General Relativity, Addison-Wesley, 2003. A graduate-level general relativity textbook.

- A. S. Eddington, Space, Time and Gravitation, Cambridge University Press, reprint of 1920 ed.

- A. Gefter, "Putting Einstein to the Test", Sky and Telescope July 2005, p. 38. A popular discussion of tests of general relativity.

- H. Ohanian and R. Ruffini, Gravitation and Spacetime, 2nd Edition Norton, New York, 1994, ISBN 0-393-96501-5. A general relativity textbook.

- Pauli, Wolfgang Ernst (1958). "Part IV. General Theory of Relativity". Theory of Relativity. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-64152-2.

- C. M. Will, Theory and Experiment in Gravitational Physics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1993). A standard technical reference.

- C. M. Will, Was Einstein Right?: Putting General Relativity to the Test, Basic Books (1993). This is a popular account of tests of general relativity.

Living Reviews papers

- Ashby, Neil (2003). "Relativity in the Global Positioning System". Living Reviews in Relativity. 6 (1): 1. S2CID 12506785.

- Will, Clifford M. (2014). "The Confrontation between General Relativity and Experiment". Living Reviews in Relativity. 17 (1): 4. PMID 28179848. An online, technical review, covering much of the material in Theory and experiment in gravitational physics. It is less comprehensive but more up to date.

External links

- the USENET Relativity FAQ experiments page

- Mathpages article on Mercury's perihelion shift (for amount of observed and GR shifts).