The Boat Race 1860

| 17th Boat Race | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 31 March 1860 | ||

| Winner | Cambridge | ||

| Margin of victory | 1 length | ||

| Winning time | 26 minutes 5 seconds | ||

| Overall record (Cambridge–Oxford) | 10–7 | ||

| Umpire | Joseph William Chitty (Oxford) | ||

| |||

The 17th Boat Race took place on 31 March 1860. Held annually, the Boat Race is a side-by-side rowing race between crews from the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge along the River Thames. It was the first time in the history of the event that the race had to be restarted as a result of an obstruction. Cambridge won the event by one length, in the slowest time ever.

Background

The Boat Race is a side-by-side rowing competition between the University of Oxford (sometimes referred to as the "Dark Blues")[1] and the University of Cambridge (sometimes referred to as the "Light Blues").[1] The race was first held in 1829, and since 1845 has taken place on the 4.2-mile (6.8 km) Championship Course on the River Thames in southwest London.[2][3] Oxford went into the race as reigning champions, having defeated Cambridge as they sank in the previous year's race. Cambridge led overall with nine wins to Oxford's seven.[4]

The challenge to race was sent by the president of the Cambridge University Boat Club to the president of the Oxford University Boat Club in the October term, with subsequent agreement to compete on 30 March 1860. However, this was soon deemed unacceptable: the Cambridge crew were required to take examinations in the days prior and the tide on that day was "inconvenient". As such, it was agreed to hold the race the following day, on 31 March.[5] Oxford were initially considered the favourites, but after Cambridge's practice rows, the odds evened.[6]

Cambridge's boat was built specifically for the race by Edward Searle of Simmons boat yard and was 57.5 feet (17.5 m) in length. The Oxford vessel was the same as that used in the previous year's race, a 54-foot (16 m) long boat built by Matthew Taylor of Newcastle.[7] The race was umpired by Joseph William Chitty who had rowed for Oxford twice in 1849 (in the March and December races) and the 1852 race.[8]

Crews

Both crews were downselected from pairs of trials eights.[9] The Oxford crew weighed an average of 11 st 12.5 lb (75.3 kg), 2.75 pounds (1.2 kg) per rower more than their Light Blue opposition.[10] Each crew contained four members who had featured in the previous year's race: Chaytor and Morland represented Cambridge again, while Fairbairn and Hall competed in their third race. Meanwhile, Morrison, Baxter and Robarts represented Oxford for the second time, with Risley making his third appearance in the event.[10]

| Seat | Cambridge |

Oxford | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | College | Weight | Name | College | Weight | |||

Bow |

S. Heathcote | 1st Trinity | 10 st 3 lb | J. N. MacQueen | University | 11 st 7 lb | ||

| 2 | H. J. Chaytor | Jesus | 11 st 4 lb | G. Norsworthy | Magdalen | 11 st 0 lb | ||

| 3 | D. Ingles | 1st Trinity | 10 st 13 lb | T. F. Halsey | Christ Church | 11 st 11 lb | ||

| 4 | J. S. Blake | Corpus Christi | 12 st 9 lb | J. F. Young | Corpus Christi | 12 st 8 lb | ||

| 5 | M. Coventry | Trinity Hall | 12 st 8 lb | G. Morrison (P) | Balliol | 12 st 13 lb | ||

| 6 | B. N. Cherry | Clare Hall | 12 st 1 lb | H. F. Baxter | Brasenose | 11 st 7 lb | ||

| 7 | A. H. Fairbairn | 2nd Trinity | 11 st 10 lb | C. I. Strong | University | 11 st 2 lb | ||

Stroke |

J. Hall (P) | Magdalene | 10 st 4 lb | R. W. Risley | Exeter | 11 st 8 lb | ||

| Cox | J. T. Morland | Trinity | 9 st 0 lb | A. J. Robarts | Christ Church | 9 st 9 lb | ||

| Source:[10] (P) – boat club president[11] | ||||||||

Race

For the first time in a University Race, there was a false start, for no sooner was the word given than an ugly old wherry came creeping across the bows of the boats, and had not Mr Searle with the greatest presence of mind instantly by voice and gesture recalled them, most unpleasant consequences might have been the result.

MacMichael[7]

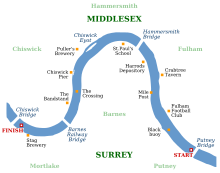

The crowd lining the banks of the Thames was "immense", while the weather was "drizzly and windy".[6] Oxford won the toss and elected to start from the Middlesex station handing the Surrey side of the river to Cambridge. Immediately after the starter, Edward Searle, had commanded the boats to commence, a wherry interrupted proceedings, blocking the boats' passage and forcing Searle to declare a false start. It was the first time in Boat Race history that the event was required to be restarted.[7]

Neither crew made a good start, but Cambridge took an early lead. Oxford had recovered to draw level by the "Star and Garter" pub and led by half a length by Craven Cottage.[12] The Dark Blues were nearly clear by the "Crab Tree" pub and their cox Robarts steered across in an attempt to take clear water. Cambridge's cox Morland called for a push to defend their course causing the crews to clash oars.[13] They passed through the central pier of Hammersmith Bridge, with Cambridge holding a 3-foot (0.9 m) lead, which they extended to half a length around Chiswick Reach. By Barnes Bridge the Light Blues held a length-and-a-half lead. They passed the "Ship Tavern" at Mortlake, winning by a length in a time of 26 minutes 5 seconds.[14] As of 2019, this remains the slowest winning time in the history of the event.[4]

References

Notes

- ^ a b "Dark Blues aim to punch above their weight". The Observer. 6 April 2003. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ Smith, Oliver (25 March 2014). "University Boat Race 2014: spectators' guide". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ "The Course". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Boat Race – Results". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ MacMichael, p. 270

- ^ a b MacMichael, p. 273

- ^ a b c MacMichael, p. 274

- ^ Burnell, pp. 49, 97

- ^ MacMichael, pp. 271–272

- ^ a b c MacMichael, p. 277

- ^ Burnell, pp. 50–51

- ^ MacMichael, pp. 274–275

- ^ MacMichael, p. 275

- ^ MacMichael, pp. 275–276

Bibliography

- ISBN 0950063878.

- Dodd, Christopher (1983). The Oxford & Cambridge Boat Race. Stanley Paul. ISBN 0091513405.

- Drinkwater, G. C.; Sanders, T. R. B. (1929). The University Boat Race – Official Centenary History. Cassell & Company, Ltd.

- MacMichael, William Fisher (1870). The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Races: From A.D. 1829 to 1869. Deighton. p. 37.

boat race oxford cambridge.