The Dorilton

Dorilton | |

New York City Landmark No. 0858

| |

| |

| |

| Location | 171 W. 71st St., Manhattan, New York |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°46′41″N 73°58′54″W / 40.77806°N 73.98167°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1900 |

| Architect | Janes & Leo |

| Architectural style | Beaux Arts |

| NRHP reference No. | 83001723[1] |

| NYCL No. | 0858 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 8, 1983 |

| Designated NYCL | September 8, 1983 |

The Dorilton is a luxury residential

The Dorilton is roughly H-shaped in plan, with recessed

Weed bought the site in February 1900 and hired the firm of Janes & Leo to design a twelve-story apartment hotel on the site. The building cost $750,000 and was intended to attract middle-class residents who otherwise would not have lived in apartments. Storefronts on the ground floor were added after 1919, many decorative elements were removed or had deteriorated by the 1950s. The Dorilton was sold several times over the years before becoming a housing cooperative in 1984. The exterior was restored in the late 1980s and again in the 1990s, and the interior spaces were restored in the mid-2010s.

Site

The Dorilton is at 171 West 71st Street, at the northeast corner with

The building is near several other structures, including the Rutgers Presbyterian Church and the Ansonia apartments to the northwest, the Apple Bank Building one block north, the Triad Theatre to the east, and the Church of the Blessed Sacrament and the Pythian Temple to the southwest.[2][3] Directly west of the Dorilton is Verdi Square and an entrance for the New York City Subway's 72nd Street station.[3]

Architecture

The building was designed by

Form and facade

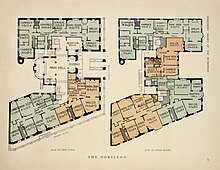

The Dorilton is roughly H-shaped in plan, with recessed

The facade is divided into three horizontal sections, similar to the base, shaft, and

The midsection is clad largely in brick, except for the corners, which have limestone

The tenth story once contained another balcony, decorated with a balustrade and urns.

Features

Originally, the Dorilton's entrance vestibule was decorated with

Apartments

The upper stories originally had four apartments per floor.[13] These apartments were arranged in suites with five, seven, eight, or ten rooms;[25] there were one to four bedrooms in each unit.[26] By 1923, there were 48 units in total, each with five to eight rooms, and each floor contained two to three bathrooms that were shared by all of the apartments.[27] When the building was developed, the space under the mansard roof was intended to be leased out as artists' studios.[25] The top of the building contained a roof garden, in addition to "sun parlors" measuring 35 by 35 feet (11 by 11 m).[12]

The units were decorated with mahogany, oak, white-enamel, and maple trim. The hallways contained paneled

Over the years, many of the apartments have been divided into smaller units. These apartments retain some of their original decorations, such as paneling, Queen Anne style fireplaces, French doors, and round window bays.[13] By the early 21st century, the building had 60 apartments, which vary in layout, and some of the units are duplexes. For instance, one of the eighth-floor duplexes has four bedrooms, two each on the upper and lower levels, in addition to various other rooms.[30] Another unit, a two-bedroom apartment, contains a living room, a dining room, a kitchen, and outdoor terrace.[31] Some of the apartments have fireplaces in both the living room and the dining room, in addition to curved bay windows.[30] Other apartments have design elements such as private libraries, French doors, and balconies;[32] one of the penthouses has a 2,000-square-foot (190 m2) terrace with a Jacuzzi, dining area, and plants.[33]

History

The city's first subway line was developed starting in the late 1890s, and it opened in 1904 with a station at Broadway and 72nd Street.[34] The construction of the subway spurred the development of high-rise apartment buildings on Broadway, such as the Ansonia and the Dorilton.[21] Before the routing of the subway line had been finalized, in early 1899, developer Hamilton M. Weed paid $175,500 for a plot on the corner of Broadway and 71st Street in February 1899.[35][a][26]

Apartment house

1900s to 1920s

In February 1900, the media announced that Weed had bought the plot from Oppenheimer & Hamershlag and had hired the firm of Janes & Leo to design a twelve-story

The building was known as the Dorilton when it was completed in 1902 for $750,000.[26] According to writer Elizabeth Hawes, the "Dorilton" name was intended to "validate the decision to live in an apartment" and "give the building a sense of permanence and longevity and breeding".[44] The elaborate design was intended to attract middle- and upper-class people who would have otherwise lived in townhouses.[45] Weed sold the Dorilton in March 1902 to a group of investors from Buffalo, New York, and Providence, Rhode Island; the building was valued at $1.25 million.[4][35] At the time, only one of the building's 48 units was vacant.[46] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) wrote that the building was frequented by musicians and actors.[47] Among the building's early tenants were actress Bernice Golden, who was the ex-wife of F. Augustus Heinze,[48] as well as businessman Henry Osborne Havemeyer.[49] The building's owner, the Dorilton Corporation, filed plans in 1908 to renovate the first story by adding a new entrance with a canopy.[50]

The Dorilton Corporation sold the building in November 1915 to an investor, at which point the structure was valued at $1.5 million.[51][52] The buyer, George Noakes, gave the Dorilton Corporation two apartment houses as partial payment.[53][54] Noakes took over a $674,000 mortgage that had been placed on the property.[53] Noakes resold the Dorilton in 1919 to Sydney H, Sonn, the president of the Transit Realty Company, at which point it was fully occupied and provided $111,000 a year in rental income.[55][56] Subsequently, Sonn added storefronts and renovated the interior.[27] Frederick Brown purchased the Dorilton in February 1923 at an assessed value of $1.5 million; by then, annual rental income from the building had increased to $200,000.[7] Three months later, Brown resold the building to a syndicate of investors led by Max Raymond. The New-York Tribune reported that the building had six stores and 48 apartments.[27]

1930s to 1970s

The Dry Dock Savings Bank initiated foreclosure proceedings against the Dorilton in 1938, as the owners, the Seventy-first Street and Broadway Corporation, had failed to pay $1,263,904 on the mortgage.[57] The bank acquired the building at a foreclosure auction that month.[58] By October 1939, the building's managing agent reported that the Dorilton was fully rented.[59] Isaac Prussin bought the building from the bank in 1945 at an assessed valuation of $900,000.[60][61] At the time of Prussin's purchase, the building contained three stores, as well as 55 apartments with between four and seven rooms each.[60] Prussin co-owned the Dorilton with Irving Stolz for five years. The men sold the building in February 1950 to a syndicate represented by Max Uviller; at the time, the building was worth $655,000.[62]

One of the Dorilton's cornices was removed at some point after 1945,[63] and many decorative elements were removed or had deteriorated by the 1950s.[26] A syndicate led by Sam Sobel bought the building in 1956 at an assessed valuation of $700,000; they assumed the building's $440,000 mortgage and paid $260,000 in cash. The buyers planned to spend $150,000 on upgrading the elevators and installing a central air-conditioning system. At the time, the building's ground floor contained the Fifth Avenue Bar and the Stanwood Cafeteria, while the upper stories included 60 standard apartments and two penthouse apartments.[64] The Dorilton's tenants by the 1960s included vocal coach Phil Moore, who operated a studio in the building.[65] The LPC proposed designating the building's facade as a city landmark in May 1974[66] and voted that October to designate the building as a New York City landmark.[67] The Dorilton was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.[1][68]

Co-op

The Dorilton became a housing cooperative in 1984. The next year, workers began renovating the Dorilton, particularly its roof; John Wright Stephens and Jonathan Williams were hired as the renovation architects. Stephens and Williams repainted the eleventh-story facade in a trompe-l'œil pattern, since there was not enough money to fund the restoration of cornices on the 10th and 11th stories.[26] According to a shareholder for the co-op, this was the first time that the LPC had allowed a trompe-l'œil pattern to be installed in lieu of original ornamentation. The restoration of the roof, which included rebuilding the cresting and dormers, was completed in 1990 at a cost of $1.5 million.[26] In addition, in the late 1980s, commercial landlord Crescent Properties bought the master lease for the stores at the Dorilton's base for $2.5 million. Crescent planned to divide a former doughnut shop at the building's base into three smaller storefronts that paid nearly twelve times as much monthly rent.[69]

The exterior masonry, decorative terra-cotta work and chimneys and roof were restored in 1998 by the Walter B. Melvin architectural firm.[70][71] The signage outside the building's storefronts was removed during the 1990s.[17] During the first decade of the 21st century, interior designer Lucretia Moroni renovated the building's common spaces for $172,800. The project included installing new cast-iron benches in the entrance courtyard, as well as installing seats in the foyer and lobby, which had never previously had any seating areas. In addition, Moroni repainted the lobby's walls in pale green, complementing the courtyard's plantings, and repainted the stairways and walls in yellow.[72] Among the residents of the co-op was actor Nathan Lane.[32][73]

Critical reception

When the building was under construction, the New-York Tribune wrote that "the imposing architecture of this lofty structure has, since the completion of its ornate facades and picturesque, domed roof, attracted the attention of every resident of the Upper West Side".[25] Montgomery Schuyler criticized the design in 1902, describing "the wild yell with which the fronts exclaim, 'Look at me,' as if somebody were going to miss seeing a building of this area, 12 stories high".[26][20] Schuyler further regarded the roof as oversized, saying: "this roof, under pretence of being a roof, three full stories in tinware, including the parapet story, ostensibly of brick and stone, with scarcely any reduction in area from its substructure, and the fact would give it a squeezed and skintight look, no matter how it was treated in detail. But it is treated with extreme cruelty."[24]

In 1978, Peter Carlsen and Christopher Gray wrote for GQ magazine that "this fine madness, thought to be indigestible for decades, suddenly seems worth taking a little more seriously".[29] Paul Goldberger wrote of the building the next year: "Now the building seems more to be pitied than censored, a rather too eager-to-please piece of Second Empire foppery",[18] while another GQ article in 1979 described the Dorilton's design as "outlandish".[74] In the 1983 book New York 1900, Robert A. M. Stern and his co-authors wrote that the building's "almost overblown Modern French" design contrasted with the "restrained, almost severe Classicism" of earlier townhouses designed by Janes & Leo.[37] Architecture historian Andrew Dolkart regarded the Dorilton as "the most flamboyant apartment house in New York", with its striking, "French-inspired" sculpted figures and an enormous iron gate "reminiscent of those that guard French palaces."[8] Architecture historian Francis Morrone considered it one of the city's great apartment buildings.[9] The novelist Thane Rosenbaum wrote that the "white, ghostly faces" of the facade's sculptures "look not so much threatening as beleaguered".[75]

See also

- List of buildings and structures on Broadway in Manhattan

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 59th to 110th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 59th to 110th Streets

References

Notes

- ^ The New York Times gives an alternate figure of $275,000.[26]

Citations

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8129-3107-5.

- ^ a b c "171 West 71 Street, 10023". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ a b "Another Big B'way Apartment Sold". New York Herald. March 13, 1919. p. 13. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ a b "Apartments, Flats and Tenements". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 65, no. 1665. February 3, 1900. p. 195. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 24, 2023 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ ProQuest 1221773202.

- ^ OCLC 52695711.

- ^ OCLC 50002477.

- ^ "The Dorilton: photos and description". Archived from the original on October 18, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Landmarks Preservation Commission 1974, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Dorilton". Buffalo Morning Express. April 6, 1902. p. 8. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k National Park Service 1983, p. 2.

- ^ Architectural Record 1902, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1974, p. 1; National Park Service 1983, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Architectural Record 1902, p. 223.

- ^ from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ OCLC 4835328– via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Architectural Record 1902, p. 222.

- ^ a b Architectural Record 1902, p. 224.

- ^ a b c d Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, p. 383.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1974, p. 2; National Park Service 1983, p. 2.

- ^ Architectural Record 1902, pp. 223–224.

- ^ a b Architectural Record 1902, p. 225.

- ^ from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ ProQuest 1237271854.

- ^ a b Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, pp. 383–385.

- ^ ProQuest 2478052784.

- ^ a b Horsley, Carter B. (September 30, 1990). "The Dorilton, 171 West 71st Street". CityRealty. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ Cohen, Michelle (October 11, 2019). "Is this gorgeous two-bedroom Upper West Side co-op in the Dorilton a steal at $1.9M?". 6sqft. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ Walker, James Blaine (1918). Fifty Years of Rapid Transit — 1864 to 1917. New York, N.Y.: Law Printing. pp. 148, 186.

- ^ a b "North of 59th Street". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 69, no. 1776. March 29, 1902. p. 556. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 24, 2023 – via columbia.edu.

- from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, p. 373.

- from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ "Of Interest to the Building Trades". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 69, no. 1767. January 25, 1902. p. 165. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 24, 2023 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, pp. 382–383.

- ProQuest 570887111.

- ^ "The Apartment Houses of New York". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 85, no. 2193. March 26, 1910. pp. 644–645. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 24, 2023 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Building Loan Contracts". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 67, no. 1716. February 2, 1901. p. 210. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 24, 2023 – via columbia.edu.

- from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ProQuest 212847738.

- ^ "The Sale of the Dorilton". New-York Tribune. March 30, 1902. p. 11. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1974, p. 2.

- ^ "Mrs. F. A. Heinze Dead". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 3, 1913. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 16, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ "To Improve Canal St. Building". New-York Tribune. March 5, 1908. p. 5. Archived from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ProQuest 575463452.

- ^ from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ProQuest 575463863.

- from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ProQuest 575993753.

- from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ProQuest 1262383948.

- ^ from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ProQuest 1269812113.

- ProQuest 1326820256.

- from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ProQuest 226825675.

- from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ProQuest 424798267.

- ProQuest 219123295.

- ^ "The Dorilton, 171 West 71st Street " Archived December 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Walter B. Melvin Architects, LLC. Accessed December 10, 2015.

- ^ Gobrecht, Larry E. (August 1982). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: The Dorilton". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2011. See also: "Accompanying six photos". Archived from the original on October 19, 2012.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ Rebong, Kevin (July 15, 2022). "Actor Nathan Lane Buys Upper West Side Co-Op". The Real Deal. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ProQuest 2478052784.

- from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

Sources

- Dorilton (PDF) (Report). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. September 8, 1983.

- The Dorilton (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 8, 1974.

- "New York City-Greater New York: - The Dorilton; an Architectural Aberration" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 12. June 1902.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Gregory; Massengale, John Montague (1983). New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890–1915. New York: Rizzoli. OCLC 9829395.

External links

Media related to The Dorilton at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Dorilton at Wikimedia Commons