The Garden Tomb

31°47′1.87″N 35°13′47.92″E / 31.7838528°N 35.2299778°E

The Garden Tomb (Arabic: بستان قبر المسيح,

The organization that owns and maintains the Garden Tomb is a

The rock-cut tomb was unearthed in 1867. The Israeli archaeologist Gabriel Barkay points out that the tomb does not contain any features indicative of the 1st century CE, when Jesus was buried, and argues that the tomb was likely created in the 8th–7th centuries BCE.[7] The Italian archeologist Ricardo Lufrani argues instead that it should be dated to the Hellenistic era, the 4th–2nd centuries BCE. The re-use of old tombs was not an uncommon practice in ancient times, but this would seem to contradict the biblical text that speaks of a new, not reused, tomb made for himself by Joseph of Arimathea (Matthew 27:57–60, John 19:41).

Site inside the church: attitudes throughout history

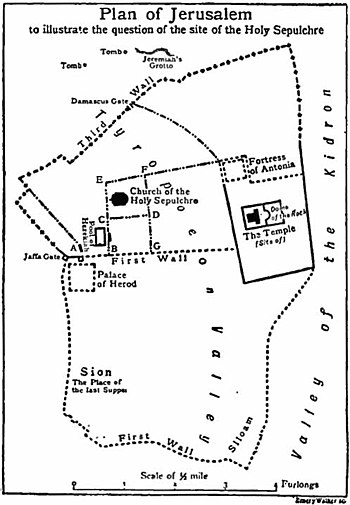

According to the Bible, Jesus was crucified near the city of Jerusalem, outside its walls,[8] and there has always been concern on the issue of the tomb of Jesus being inside the city walls, with various explanations coming up during the centuries.

Early medieval views

For example, as early as 754 AD

Doubts after Reformation

After the

19th-century Protestant doubts

In 1812, also Edward D. Clarke rejected the traditional location as a "mere delusion, a monkish juggle"[15] and suggested instead that the crucifixion took place just outside Zion Gate.[12] During the 19th century travel from Europe to the Ottoman Empire became easier and therefore more common, especially in the late 1830s due to the reforms of the Egyptian ruler, Muhammad Ali.[16][17] The subsequent influx of Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem included more Protestants who doubted the authenticity of the traditional holy sites – doubts which were exacerbated by the fact that Protestants had no territorial claims at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and by the feeling of Protestant pilgrims that it was an unnatural setting for contemplation and prayer.[16]

In 1841, Dr. Edward Robinson's "Biblical Researches in Palestine",[18] at that time considered the standard work on the topography and archaeology of the Holy Land, argued against the authenticity of the traditional location, concluding: "Golgotha and the Tomb shown in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are not upon the real places of the Crucifixion and Resurrection". Robinson argued that the traditional location would have been within the city walls also during the Herodian era, primarily due to topographical considerations. Robinson was careful not to propose an alternative site and had concluded that it would be impossible to identify the true location of the holy places. However, he did suggest that the crucifixion would have taken place somewhere on the road to Jaffa or the road to Damascus.[12] Skull Hill and the Garden Tomb are located in close proximity to the Damascus road, about 200 m. from Damascus Gate.

Contemporary scholarship

Contemporary scholars, such as Professor Dan Bahat, one of Israel's leading archaeologists, have concluded that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is located in an area which was outside the city walls in the days of Jesus and therefore indeed constitutes a plausible location for the crucifixion and burial of Jesus.[19]

Discovery

Skull Hill identified as Calvary

Motivated by these concerns, some Protestants in the nineteenth century looked elsewhere in the attempt to locate the site of Christ's crucifixion, burial and resurrection.

Otto Thenius

In 1842, heavily relying on Robinson's research,

Fisher Howe

A few years later the same identification was endorsed by the American industrialist Fisher Howe,

H. B. Tristram

Another early proponent of the theory that Skull Hill is Golgotha was the English scholar and clergyman Canon Henry Baker Tristram, who suggested that identification in 1858 during his first visit to the Holy Land, chiefly because of its proximity to the northern gate, and hence also to the Antonia Fortress, the traditional site of Christ's trial. (Canon Tristram was also one of the advocates of purchasing the nearby Garden Tomb in 1893.)[26]

Claude R. Conder

Another prominent proponent of the "new Calvary" was

There are those who would willingly look upon it as the real place of the Saviour's Tomb, but I confess that, for myself, having twice witnessed the annual orgy which disgraces its walls, the annual imposture which is countenanced by its priests, and the fierce emotions of sectarian hate and blind fanaticism which are called forth by the supposed miracle, and remembering the tale of blood connected with the history of the Church, I should be loth to think that the Sacred Tomb had been a witness for so many years of so much human ignorance, folly, and crime.

Based on topographical and textual considerations, Conder argued that it would be dangerous and unlikely, from a town-defense point of view, for the walls to have previously been east of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, concluding that the Church would have been inside the city walls and thus not the authentic tomb of Christ.

Proponents in the 1870s

Additionally, in the 1870s the site of Skull Hill was being strongly promoted by several notable figures in Jerusalem, including the American consul to Jerusalem,

In 1879 the French scholar Ernest Renan, author of the influential and controversial Life of Jesus also considered this view as a possibility in one of the later editions of his book.[12]

General Gordon

However, the most famous proponent of the view that Skull Hill is the biblical Golgotha was

Gordon went beyond Howe and Conder to passionately propose additional arguments, which he himself confessed were "more fanciful" and imaginative. Gordon proposed a

I feel, for myself, convinced that the Hill near the Damascus Gate is Golgotha. ... From it, you can see the Temple, the Mount of Olives and the bulk of Jerusalem. His stretched out arms would, as it were, embrace it: "all day long have I stretched out my arms" [cf. Isaiah 65:2]. Close to it is the slaughter-house of Jerusalem; quite pools of blood are lying there. It is covered with tombs of Muslim; There are many rock-hewn caves; and gardens surround it. Now, the place of execution in our Lord's time must have been, and continued to be, an unclean place ... so, to me, this hill is left bare ever since it was first used as a place of execution. ... It is very nice to see it so plain and simple, instead of having a huge church built on it.

— Charles George Gordon, Letters of General C. G. Gordon to his Sister M. A. Gordon(London: Macmillan 1888), pp. 289–290

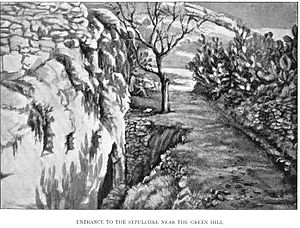

Garden Tomb identified as Jesus' tomb

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre has the tomb just a few yards away from Golgotha, corresponding with the account of John the Evangelist: "Now in the place where he was crucified there was a garden; and in the garden a new sepulchre, wherein was never man yet laid." KJV (John 19:41). In the latter half of the 19th century a number of tombs had also been found near Gordon's Golgotha, and Gordon concluded that one of them must have been the tomb of Jesus. John also specifies that Jesus' tomb was located in a garden (John 19:41); consequently, an ancient

Evangelicals and other Protestants consider the site to be the tomb of Jesus.[40]

-

A view of the Garden Tomb from the 1930s

-

Panel near the tomb

-

Inside the tomb

-

Inside the tomb

-

Inside the tomb

Affiliation

The garden is administered by the Garden Tomb Association, a member of the Evangelical Alliance of Israel and the World Evangelical Alliance.[41]

Archaeological investigation and critical analysis

Golgotha

In the church

In the 20th century, archaeological findings enhanced the discussion concerning the authenticity of the traditional site at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre:

- Prior to Constantine's time (r. 306–337), the site was a temple to Venus,[42] built by Hadrian[43] some time after 130.[citation needed]

- Archaeology suggests that the traditional tomb would have been within Hadrian's temple, or likely to have been destroyed under the temple's heavy retaining wall.[44][19][verification needed]

- The temple's location complies with the typical layout of Roman cities (i.e. adjacent to the main east-west road), rather than necessarily being a deliberate act of contempt for Christianity, as claimed in the past.[citation needed]

- A spurwould be required for the rockface to have included both the alleged site of the tomb and the tombs beyond the western end of the church.

- The tombs west of the traditional site are dated to the first century, indicating that the site was outside the city at that time.[45]

Knoll next to Garden Tomb

Besides the skull-like appearance (a modern-day argument), there are a few other details put forward in favour of the identification of Skull Hill as Golgotha. The location of the site would have made executions carried out there a highly visible sight to people using the main road leading north from the city; the presence of the skull-featured knoll in the background would have added to the deterrent effect.

Ancient views

Christian traditions

An extra-biblical Christian legend maintains that Golgotha (lit. "the skull") is

The Garden Tomb

The earliest detailed investigation of the tomb itself was a brief report prepared in 1874 by Conrad Schick, a German architect, archaeologist and Protestant missionary, but the fullest archaeological study of the area has been the seminal investigation by Gabriel Barkay, professor of Biblical archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and at Bar-Ilan University, during the late twentieth century.

The tomb has two chambers, the second to the right of the first, with stone benches along the back wall of the first chamber, and along the sides of each wall in the second chamber, except the wall joining it to the first chamber; the benches have been heavily damaged but are still discernible.[7] The edge of the groove outside the tomb has a diagonal edge, which would be unable to hold a stone slab in place (the slab would just fall out);[7] additionally, known tombs of the rolling-stone type use vertical walls on either side of the entrance to hold the stone, not a groove on the ground.[7]

Barkay concluded that:

- The tomb is far too old to be the tomb of Jesus, as it is typical of the 8th–7th centuries BCE, showing a configuration which fell out of use after that period. It fits well into a wider First Temple period which also includes the nearby tombs on the grounds of the Basilica of St Stephen.[7]

- The groove was a water trough, built by the 11th-century Crusaders for donkeys/mules.[7]

- The cistern was built as part of the same stable complex as the groove.[7]

- The waterproofing on the cistern is of the type used by the Crusaders, and the cistern must date to that era.[7]

In 1986, Barkay criticized defenders of the location of the garden and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre for making more theological and apologetic than scientific arguments.[49]

In 2010, the director of the garden, Richard Meryon, claimed in an interview with

In 2005 an Iron Age II cylinder seal was excavated, thought to be debris from nearby tombs.[51]

Reception by Christian denominations

Due to the archaeological issues the Garden Tomb site raises, several scholars have rejected its claim to be Jesus' tomb.

The Garden Tomb has been the most favoured candidate site among leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[56][57]

Major Christian denominations, including the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches, do not accept the Garden Tomb as being the tomb of Jesus and hold fast to the traditional location at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. However, many may also visit the site in order to see an ancient tomb in a location evocative of the situation described in John 19:41–42.[dubious ][citation needed]

The British author, barrister and civil servant, Arthur William Crawley Boevey (1845–1913) produced for the Committee of the Garden Tomb Maintenance Fund in Jerusalem an introduction and guidebook to the site in 1894. The booklet has subsequently been revised and enlarged on several occasions, including by Mabel Bent in the early 1920s.[58]

See also

- Zedekiah's Cave, part of the same ancient quarries

References

- ^ Kochav (1999)

- ISBN 0-664-22230-7.

- ISBN 9780822383307.

- ^ The Garden Tomb

- ISBN 0-664-22230-7.

- ^ Website of The Garden Tomb (Jerusalem) Association

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Barkay (1986)

- ^ Mark 15:20; John 19:20; Hebrews 13:12

- ISBN 9780790505381. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Talbot, C. H. The Anglo-Saxon Missionaries in Germany, Being the Lives of SS. Willibrord, Boniface, Leoba and Lebuin together with the Hodoepericon of St. Willibald and a selection from the correspondence of St. Boniface, (London and New York: Sheed and Ward, 1954) p. 165

- ^ Thomas Wright ed., Early Travels in Palestine (London 1848), p. 37

- ^ a b c d e f g Wilson (1906)

- ^ Franciscus Quaresmius, Elucidatio Terrae Sanctae (Antwerp 1639), lib. 5, cap. 14

- ^ Korte, Jonas (1751). Reise nach dem weiland gelobten, nun aber seit siebenzehn hundert Jahren unter dem Fluche liegenden Lande, wie auch nach Egypten, dem Berg Libanon, Syrien und Mesopotamien (3rd ed.). Halle: Joh. Christian Grunert; after 1st ed. by Jonas Korte, Altona-Hamburg (1741). p. 6. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ Clarke, Edward Daniel (1817). Travels in various countries of Europe, Asia and Africa: Part II – Greece, Egypt, and the Holy Land, section I (vol. IV), 4th edition, London, p. 335

- ^ a b c Kochav (1995)

- Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 142, 3 (London 2010), pp. 199–216

- ^ Robinson, Edward. Biblical Researches in Palestine.

- ^ a b Bahat (1986)

- ^ Thenius, Otto (1842). "Golgatha et Sanctum Sepulchrum" (in Latin). In Zeitschrift fir die historische Theologie.

- ^ White, Bill (1989. A Special Place: The Story of the Garden Tomb).

- ^ McBirnie, William Steuart (1975). The Search for the Authentic Tomb of Jesus.

- ^ Prentiss, George Lewis (1889). The Union Theological Seminary in the city of New York: historical and biographical sketches of its first fifty years. New York.

- ^ Howe, Fisher (1853), Turkey, Greece, and Palestine, Glasgow; also published as Howe, Fisher (1853), Oriental and sacred scenes, from notes of travel in Greece, Turkey, and Palestine, New York.

- ^ Howe, Fisher (1871). The True Site of Calvary, and Suggestions relating to the Crucifixion. New York .

- ^ "The Site of the Holy Sepulchre" in Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement (London 1893), pp. 80–91

- ^ Conder, Claude R.(2004) [1909]. The City of Jerusalem.

- ^ Claude R. Conder, Tent Work in Palestine: A Record of Discovery and Adventure, Vol. I (London, 1878), pp. 361–376

- ^ Warren, Charles and Conder, Claude R. (1884). The Survey of Western Palestine: Jerusalem. The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London, pp. 380–393.

- ISBN 0-664-22230-7.

- ^ Hanauer, J. E. "Notes on Skull Hill" in Palestine Exploration Fund – Quarterly Statement for 1894

- ^ Wilson (1906), p. 115

- ^ a b Schaff (1878)

- ^ Millgram, Abraham E. (1990). Jerusalem Curiosities, pp. 152–156

- ^ Peled, Ron (3 October 2006). "The Garden Tomb – Secret of the missing tomb". Ynetnews.

- ^ "Da'at: Jewish Heritage Tours and Educational Travel".

- ^ Seth J. Frantzman and Ruth Kark, "General Gordon, The Palestine Exploration Fund and the Origins of 'Gordon's Calvary' in the Holy Land", Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 140, 2 (2008), pp. 1–18

- ^ Charles George Gordon, "Eden and Golgotha", Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement (London 1885), pp. 79–81

- ^ Wilson (1906), p. 120

- ^ Wesley G. Pippert, Jesus Christ's resurrection: Garden Tomb or Church of Holy Sepulchre?, upi.com, USA, April 7, 1985

- ^ Garden Tomb Association, Partners, gardentomb.com, UK, retrieved May 8, 2021

- )

- ISBN 9780198147855. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Corbo, Virgilio, The Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (1981)

- ^ Hachlili, Rachel (2005). Jewish Funerary Customs, Practices and Rites in the Second Temple Period.

- ^ Eusebius, Onomasticon, 365.

- ^ "Adam in the Future World". Jewish Encyclopedia (1906).

- ^ a b c Golgotha (literally, "the skull"). Jewish Encyclopedia (1906).

- ^ Gabriel Barkay, "The Garden Tomb: Was Jesus Buried Here?", Biblical Archaeology Review, vol. 12, no 2, 1986, p. 47

- ^ Melanie Lidman, Tomb with a view, Jerusalem Post, 2 April 2010

- ^ [1]Uehlinger, Christoph; Winderbaum, Ariel; Zelinger, Yehiel, " A Seventh-Century BCE Cylinder Seal from Jerusalem Depicting Worship of the Moon God’s Cult Emblem", In: Münger, Stefan; Rahn, Nancy; Wyssmann, Patrick. „Trinkt von dem Wein, den ich mischte!“ / “Drink of the wine which I have mingled!” (FS Silvia Schroer). Leuven: Peeters Publishers, pp. 552-590, 2023

- ^ Pixner, Bargil, Wege des Messias und Stätten der Urkirche, Giessen/Basel 1991, p. 275. English edition (2010): Paths of the Messaiah, p. 304. Ignatius Press: San Francisco

- ^ "Biblical Archaeology – Has Jesus' Tomb Been Identified?". byfaith.org. 1 April 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- ISBN 9781498230988.

- ISBN 9781466807136.

- ^ Tvedtnes, John A. "The Garden Tomb", Ensign, Apr. 1983.

- ^ "Bible Photos: Garden Tomb", churchofjesuschrist.org. The caption states, "Possible site of the garden tomb of Joseph of Arimathea. Some modern prophets have felt that the Savior’s body was laid in the tomb pictured here."

- ^ Arthur William Crawley Boevey, Mrs J Theodore Bent, Miss Hussey (no date). The Garden Tomb, Golgotha and the Garden of Resurrection. Committee of the Garden Tomb, London.

Bibliography

- Bahat, Dan. "Does the Holy Sepulchre Church Mark the Burial of Jesus?". Biblical Archaeology Review (May/June 1986). BAS.

- Barkay, Gabriel (24 August 2015). "The Garden Tomb". Biblical Archaeology Review (March/April 1986). BAS. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- Kochav, Sarah (1995). "The Search for a Protestant Holy Sepulchre: The Garden Tomb in Nineteenth-Century Jerusalem". S2CID 162859328.

- Kochav, Sarah (1999). Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Holy Land Revealed guides. ISBN 9789652171634. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

The Garden Tomb Society, supported by many prominent Evangelicals in the Church of England was formed to purchase the tomb and the surrounding land in 1885.

Access to cited text currently not allowed (August 2021). - ISBN 9780790503257. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- Wilson, Charles W. (1906). "Chapter X: Theories with Regard to the Position of Golgotha and the Tomb". Golgotha and The Holy Sepulchre. London: The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. pp. 103–120. Retrieved 27 August 2021. Good text scan, but with blurred illustrations and captions; or here, a darker scan, but with fully visible illustrations.

External links

- Official website

- Watson, Charles Moore (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 656–658. This contains a detailed summary of the then-current theories as to the location of the tomb, with an extensive bibliography.