The Troubles

| The Troubles | ||

|---|---|---|

mainland Europe | ||

| Result |

| |

British Armed Forces

British Armed Forces Royal Ulster Constabulary

Royal Ulster Constabulary- Irish Defence Forces

- Gardaí

- Provisional IRA(IRA)

Irish National Liberation Army (INLA)

Irish National Liberation Army (INLA)- Official IRA(OIRA)

- Continuity IRA(CIRA)

- Real IRA(RIRA)

- Irish People's Liberation Organisation (IPLO)

Ulster Defence Association (UDA)

Ulster Defence Association (UDA) Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) Red Hand Commando (RHC)

Red Hand Commando (RHC) Ulster Resistance (UR)

Ulster Resistance (UR) Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF)

Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF)- Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV)

British Army: 705

(inc. UDR)

RUC: 301

NIPS: 24

TA: 7

Other UK police: 6

Royal Air Force: 4

Royal Navy: 2

Total: 1,049[9]

INLA: 38

OIRA: 27

IPLO: 9

RIRA: 2

Total: 368[9]

UVF: 62

RHC: 4

LVF: 3

UR: 2

UPV: 1[10]

Total: 162[9]

(1,935 including ex-combatants)[9]

Total dead: 3,532[11]

Total injured: 47,500+[12]

All casualties: ~50,000[13]

The Troubles (

The conflict was primarily political and

The conflict began during a campaign by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association to end discrimination against the Catholic-nationalist minority by the Protestant-unionist government and local authorities.[35][36] The government attempted to suppress the protests. The police, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), were overwhelmingly Protestant and known for sectarianism and police brutality. The campaign was also violently opposed by Ulster loyalists, who believed it was a front for republican political activity. Increasing tensions led to the August 1969 riots and the deployment of British troops, in what became the British Army's longest operation.[37] "Peace walls" were built in some areas to keep the two communities apart. Some Catholics initially welcomed the British Army as a more neutral force than the RUC, but soon came to see it as hostile and biased, particularly after Bloody Sunday in 1972.[38]

The main

More than 3,500 people were killed in the conflict, of whom 52% were

Name

The word "troubles" has been used as a synonym for violent conflict for centuries. It was used to describe the 17th-century

Background

1609–1791

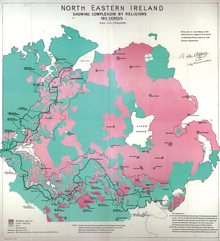

In 1609, Scottish and English settlers, known as planters, were given land

1791–1912

Following the foundation of the

With the Acts of Union 1800 (which came into force on 1 January 1801), a new political framework was formed with the abolition of the Irish Parliament and incorporation of Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The result was a closer tie between Anglicans and the formerly republican Presbyterians as part of a "loyal" Protestant community. Although Catholic emancipation was achieved in 1829, largely eliminating official discrimination against Roman Catholics (then around 75% of Ireland's population), Dissenters, and Jews, the Repeal Association's campaign to repeal the 1801 Union failed.

In the late 19th century, the Home Rule movement was created and served to define the divide between most nationalists (usually Catholics) who sought the restoration of an Irish Parliament, and most unionists (usually Protestants) who were afraid of being a minority under a Catholic-dominated Irish Parliament and who tended to support continuing union with Britain.

Unionists and Home Rule advocates were the main political factions in late 19th- and early 20th-century Ireland.[56]

1912–1922

By the second decade of the 20th century, Home Rule, or limited Irish self-government, was on the brink of being conceded due to the agitation of the Irish Parliamentary Party. In response to the campaign for Home Rule which started in the 1870s, unionists, mostly Protestant and largely concentrated in Ulster, had resisted both self-government and independence for Ireland, fearing for their future in an overwhelmingly Catholic country dominated by the Roman Catholic Church. In 1912, unionists led by Edward Carson signed the Ulster Covenant and pledged to resist Home Rule by force if necessary. To this end, they formed the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).[57]

In response, nationalists led by

The Irish Volunteers split, with a majority, known as the

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 partitioned the island of Ireland into two separate jurisdictions, Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland, both devolved regions of the United Kingdom. This partition of Ireland was confirmed when the Parliament of Northern Ireland exercised its right in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 to opt out of the newly established Irish Free State.[58] A part of the treaty signed in 1922 mandated that a boundary commission would sit to decide where the frontier of the northern state would be in relation to its southern neighbour. After the Irish Civil War of 1922–1923, this part of the treaty was given less priority by the new Dublin government led by W. T. Cosgrave, and was quietly dropped. As counties Fermanagh and Tyrone and border areas of Londonderry, Armagh, and Down were mainly nationalist, the Irish Boundary Commission could reduce Northern Ireland to four counties or fewer.[57] In October 1922, the Irish Free State government established the North-Eastern Boundary Bureau (NEBB), a government office which by 1925 had prepared 56 boxes of files to argue its case for areas of Northern Ireland to be transferred to the Free State.[59]

Northern Ireland remained a part of the United Kingdom, albeit under a separate system of government whereby it was given its own

1922–1966

A marginalised remnant of the

In 1920, in local elections held under

The two sides' positions became strictly defined following this period. From a unionist perspective, Northern Ireland's nationalists were inherently disloyal and determined to force unionists into a united Ireland. This threat was seen as justifying preferential treatment of unionists in housing, employment, and other fields.[

Late 1960s

There is little agreement on the exact date of the start of the Troubles. Different writers have suggested different dates. These include the formation of the modern Ulster Volunteer Force in 1966,[1] the civil rights march in Derry on 5 October 1968, the beginning of the 'Battle of the Bogside' on 12 August 1969, or the deployment of British troops on 14 August 1969.[57]

Civil rights campaign and unionist backlash

In March and April 1966, Irish nationalists/republicans held parades throughout Ireland to mark the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising. On 8 March, a group of Irish republicans dynamited Nelson's Pillar in Dublin. At the time, the IRA was weak and not engaged in armed action, but some unionists warned it was about to be revived to launch another campaign against Northern Ireland.[70][71] In April 1966, loyalists led by Ian Paisley, a Protestant fundamentalist preacher, founded the Ulster Constitution Defence Committee (UCDC). It set up a paramilitary-style wing called the Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV)[70] to oust Terence O'Neill, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. Although O'Neill was a unionist, they viewed him as being too 'soft' on the civil rights movement and opposed his policies.[72] At the same time, a loyalist group calling itself the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) emerged in the

In the mid-1960s, a non-violent

- an end to job discrimination – it showed evidence that Catholics/nationalists were less likely to be given certain jobs, especially government jobs

- an end to discrimination in housing allocation – it showed evidence that unionist-controlled local councils allocated housing to Protestants ahead of Catholics/nationalists

- one man, one vote – in Northern Ireland, only householders could vote in local elections, while in the rest of the United Kingdom all adults could vote

- an end to gerrymandering of electoral boundaries – this meant that nationalists had less voting power than unionists, even where nationalists were a majority

- reform of the police force (Royal Ulster Constabulary) – it was over 90% Protestant and criticised for sectarianism and police brutality

- repeal of the Special Powers Act – this allowed police to search without a warrant, arrest and imprison people without charge or trial, ban any assemblies or parades, and ban any publications; the Act was used almost exclusively against nationalists[70][77][78][79][80]

Some suspected and accused NICRA of being a republican front-group whose ultimate goal was to unite Ireland. Although republicans and some members of the IRA (then led by Cathal Goulding and pursuing a non-violent agenda) helped to create and drive the movement, they did not control it and were not a dominant faction within it.[57][81][82][83][84]

On 20 June 1968, civil rights activists, including nationalist Member of Parliament (MP) Austin Currie, protested against housing discrimination by squatting in a house in Caledon, County Tyrone. The local council had allocated the house to an unmarried 19-year-old Protestant (Emily Beattie, the secretary of a local UUP politician) instead of either of two large Catholic families with children.[85] RUC officers – one of whom was Beattie's brother – forcibly removed the activists.[85] Two days before the protest, the two Catholic families who had been squatting in the house next door were removed by police.[86] Currie had brought their grievance to the local council and to Stormont, but had been told to leave. The incident invigorated the civil rights movement.[87]

On 24 August 1968, the civil rights movement held its first civil rights march from Coalisland to Dungannon. Many more marches were held over the following year. Loyalists (especially members of the UPV) attacked some of the marches and held counter-demonstrations in a bid to get the marches banned.[85] Because of the lack of police reaction to the attacks, nationalists saw the RUC, which was almost wholly Protestant, as backing the loyalists and allowing the attacks to occur.[88] On 5 October 1968, a civil rights march in Derry was banned by the Northern Ireland government.[89] When marchers defied the ban, RUC officers surrounded the marchers and beat them indiscriminately and without provocation. More than 100 people were injured, including a number of nationalist politicians.[89] The incident was filmed by television news crews and shown around the world.[90] It caused outrage among Catholics and nationalists, sparking two days of rioting in Derry between nationalists and the RUC.[89]

A few days later, a student civil rights group,

In March and April 1969, loyalists bombed water and electricity installations in Northern Ireland, blaming them on the dormant IRA and elements of the civil rights movement. Some attacks left much of Belfast without power and water. Loyalists hoped the bombings would force O'Neill to resign and bring an end to any concessions to nationalists.[94][95] There were six bombings between 30 March and 26 April.[94][96] All were widely blamed on the IRA, and British soldiers were sent to guard installations. Unionist support for O'Neill waned, and on 28 April he resigned as prime minister.[94]

August 1969 riots and aftermath

On 19 April, there were clashes between NICRA marchers, the RUC, and loyalists in the Bogside. RUC officers entered the house of Samuel Devenny (42), an uninvolved Catholic civilian, and beat him along with two of his teenage daughters and a family friend.[94] One of the daughters was beaten unconscious as she lay recovering from surgery.[97] Devenny suffered a heart attack and died on 17 July from his injuries. On 13 July, RUC officers beat another Catholic civilian, Francis McCloskey (67), during clashes in Dungiven. He died of his injuries the next day.[94]

On 12 August, the loyalist Apprentice Boys of Derry were allowed to march along the edge of the Bogside. Taunts and missiles were exchanged between the loyalists and nationalist residents. After being bombarded with stones and petrol bombs from nationalists, the RUC, backed by loyalists, tried to storm the Bogside. The RUC used CS gas, armoured vehicles, and water cannons, but were kept at bay by hundreds of nationalists.[98] The continuous fighting, which became known as the Battle of the Bogside, lasted for three days.

In response to events in Derry, nationalists held protests at RUC bases in Belfast and elsewhere. Some of these led to clashes with the RUC and attacks on RUC bases. In Belfast, loyalists responded by invading nationalist districts, burning houses and businesses. There were gun battles between nationalists and the RUC and between nationalists and loyalists. A group of about 30 IRA members was involved in the fighting in Belfast. The RUC deployed Shorland armoured cars mounted with heavy Browning machine guns. The Shorlands twice opened fire on a block of flats in a nationalist district, killing a nine-year-old boy named Patrick Rooney. RUC officers opened fire on rioters in Armagh, Dungannon, and Coalisland.[57]

During the riots, on 13 August,

On 14–15 August, British troops were deployed in Operation Banner in Derry and Belfast to restore order,[102] but did not try to enter the Bogside, bringing a temporary end to the riots. Ten people had been killed,[103] among them Rooney (the first child killed by police during the conflict),[104] and 745 had been injured, including 154 who suffered gunshot wounds.[105] 154 homes and other buildings were demolished and over 400 needed repairs, of which 83% of the buildings damaged were occupied by Catholics.[105] Between July and 1 September 505 Catholic and 315 Protestant families were forced to flee their homes.[106] The Irish Army set up refugee camps in the Republic near the border (see Gormanston Camp). Nationalists initially welcomed the British Army, as they did not trust the RUC.[107]

On 9 September, the Northern Ireland Joint Security Committee met at Stormont Castle and decided that

A peace line was to be established to separate physically the Falls and the Shankill communities. Initially this would take the form of a temporary barbed wire fence which would be manned by the Army and the Police ... It was agreed that there should be no question of the peace line becoming permanent although it was acknowledged that the barriers might have to be strengthened in some locations.[108]

On 10 September, the British Army started construction of the first "peace wall".[109] It was the first of many such walls across Northern Ireland, and still stands today.[110]

After the riots, the Hunt Committee was set up to examine the RUC. It published its report on 12 October, recommending that the RUC become an unarmed force and the B Specials be disbanded. That night, loyalists took to the streets of Belfast in protest at the report. During violence in the Shankill, UVF members shot dead RUC officer Victor Arbuckle. He was the first RUC officer to be killed during the Troubles.[111] In October and December 1969, the UVF carried out a number of small bombings in the Republic of Ireland.[57]

1970s

Violence peaks and Stormont collapses

Despite the British government's attempt to do "nothing that would suggest partiality to one section of the community" and the improvement of the relationship between the Army and the local population following the Army assistance with flood relief in August 1970, the Falls Curfew and a situation that was described at the time as "an inflamed sectarian one, which is being deliberately exploited by the IRA and other extremists" meant that relations between the Catholic population and the British Army rapidly deteriorated.[112]

From 1970 to 1972, an explosion of political violence occurred in Northern Ireland. The deadliest attack in the early 1970s was the McGurk's Bar bombing by the UVF in 1971.[113] The violence peaked in 1972, when nearly 500 people, just over half of them civilians, were killed, the worst year in the entire conflict.[114]

By the end of 1971, 29 barricades were in place in

Unionists say the main reason was the formation of the Provisional IRA and Official IRA, particularly the former.[citation needed] These two groups were formed when the IRA split into the 'Provisional' and 'Official' factions. While the older IRA had embraced non-violent civil agitation,[115] the new Provisional IRA was determined to wage "armed struggle" against British rule in Northern Ireland. The new IRA was willing to take on the role of "defenders of the Catholic community",[116] rather than seeking working-class ecumenical unity across both communities.

Nationalists point to a number of events in these years to explain the upsurge in violence. One such incident was the Falls Curfew in July 1970, when 3,000 troops imposed a curfew on the nationalist Lower Falls area of Belfast, firing more than 1,500 rounds of ammunition in gun battles with the Official IRA and killing four people. Another was the introduction of internment without trial in 1971 (of 350 initial detainees, none were Protestants).[117] Moreover, due to poor intelligence,[118] very few of those interned were actually republican activists at the time, but some internees became increasingly radicalised as a result of their experiences.[57]

In August 1971, ten civilians were shot dead in the Ballymurphy massacre in Belfast. They were innocent and the killings were unjustified, according to a 2021 coroner's inquest. Nine victims were shot by the British Army.[119]

Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday was the shooting dead of thirteen unarmed men by the British Army at a proscribed anti-internment rally in Derry on 30 January 1972 (a fourteenth man died of his injuries some months later), while fifteen other civilians were wounded.[120][121] The march had been organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA). The soldiers involved were members of the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, also known as "1 Para".[122]

This was one of the most prominent events that occurred during the Troubles as it was recorded as the largest number of civilians killed in a single shooting incident.[123] Bloody Sunday greatly increased the hostility of Catholics and Irish nationalists towards the British military and government while significantly elevating tensions. As a result, the Provisional IRA gained more support, especially through rising numbers of recruits in the local areas.[124]

Following the introduction of internment, there were numerous gun battles between the British Army and both the Provisional and Official IRA. These included the Battle at Springmartin and the Battle of Lenadoon. Between 1971 and 1975, 1,981 people were interned: 1,874 were Catholic/republican, and 107 were Protestant/loyalist.[125] There were widespread allegations of abuse and even torture of detainees,[126][127] and in 1972, the "five techniques" used by the police and army for interrogation were ruled to be illegal following a British government inquiry.[128]

The Provisional IRA, or "Provos", as they became known, sought to establish themselves as the defender of the nationalist community.[129][130] The Official IRA (OIRA) began its own armed campaign in reaction to the ongoing violence. The Provisional IRA's offensive campaign began in early 1971 when the Army Council sanctioned attacks on the British Army.[131]

In 1972, the Provisional IRA killed approximately 100 members of the security forces, wounded 500 others, and carried out approximately 1,300 bombings,[132] mostly against commercial targets which they considered "the artificial economy".[further explanation needed][114][131][133] Their bombing campaign killed many civilians, notably on Bloody Friday on 21 July, when they set off 22 bombs in the centre of Belfast, killing five civilians, two British soldiers, a Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) reservist, and an Ulster Defence Association (UDA) member.[134][135][136] Ten days later, nine civilians were killed in a triple car bombing in Claudy.[137] The IRA is accused of committing this bombing but no proof for that accusation is yet published.[138][139]

In 1972, the Official IRA's campaign was largely counter-productive.

British troop concentrations peaked at 1:50 of the civilian population, the highest ratio found in the history of counterinsurgency warfare, higher than that achieved during the "Malayan Emergency"/"Anti-British National Liberation War" to which the conflict is frequently compared.[143] Operation Motorman, the military operation for the surge, was the biggest military operation in Ireland since the Irish War of Independence.[144] In total, almost 22,000 British forces were involved.[144] In the days before 31 July, about 4,000 extra troops were brought into Northern Ireland.[144]

Despite a temporary ceasefire in 1972 and talks with British officials, the Provisionals were determined to continue their campaign until the achievement of a united Ireland. The UK government in London, believing the Northern Ireland administration incapable of containing the security situation, sought to take over the control of law and order there. As this was unacceptable to the Northern Ireland Government, the British government pushed through emergency legislation (the

Sunningdale Agreement and UWC strike

In June 1973, following the publication of a British

Unionists were split over Sunningdale, which was also opposed by the IRA, whose goal remained nothing short of an end to the existence of Northern Ireland as part of the UK. Many unionists opposed the concept of power-sharing, arguing that it was not feasible to share power with nationalists who sought the destruction of the state. Perhaps more significant, however, was the unionist opposition to the "Irish dimension" and the Council of Ireland, which was perceived as being an all-Ireland parliament-in-waiting. Remarks by a young Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) councillor Hugh Logue to an audience at Trinity College Dublin that Sunningdale was the tool "by which the Unionists will be trundled off to a united Ireland" also damaged chances of significant unionist support for the agreement. In January 1974, Brian Faulkner was narrowly deposed as UUP leader and replaced by Harry West, although Faulkner retained his position as Chief Executive in the new government. A UK general election in February 1974 gave the anti-Sunningdale unionists the opportunity to test unionist opinion with the slogan "Dublin is only a Sunningdale away", and the result galvanised their support: they won 11 of the 12 seats, winning 58% of the vote with most of the rest going to nationalists and pro-Sunningdale unionists.[57][133]

Ultimately, the Sunningdale Agreement was brought down by mass action on the part of loyalist paramilitaries and workers, who formed the

Proposal of an independent Northern Ireland

Even as his government deployed troops in August 1969, Wilson ordered a secret study of whether the British military could withdraw from Northern Ireland, including all 45 bases, such as the submarine school in Derry. The study concluded that the military could do so in three months, but if increased violence collapsed civil society, Britain would have to send in troops again. Without bases, to do so would be an invasion of Ireland; Wilson thus decided against a withdrawal.[147]

Wilson's cabinet discussed the more drastic step of complete British withdrawal from an independent Northern Ireland as early as February 1969, as one of various possibilities for the region including direct rule.[148] He wrote in 1971 that Britain had "responsibility without power" there,[149] and secretly met with the IRA that year while leader of the opposition; his government in late 1974 and early 1975 again met with the IRA to negotiate a ceasefire. During the meetings, the parties discussed complete British withdrawal.[150] Although the British government publicly stated that troops would stay as long as necessary, widespread fear from the Birmingham pub bombings and other IRA attacks in Britain itself increased support among MPs and the public for a military withdrawal.[151]

The failure of Sunningdale and the effectiveness of the UWC strike against British authority were more evidence to Wilson of his 1971 statement. They led to the serious consideration in London of independence until November 1975. Had the withdrawal occurred – which Wilson supported but others, including

The British negotiations with the IRA, an illegal organisation, angered the Republic's government. It did not know what was discussed but feared that the British were considering abandoning Northern Ireland. Irish Foreign Minister Garret FitzGerald discussed in a memorandum of June 1975 the possibilities of orderly withdrawal and independence, repartition of the island, or a collapse of Northern Ireland into civil war and anarchy. The memorandum preferred a negotiated independence as the best of the three "worst case scenarios", but concluded that the Irish government could do little.[150]

The Irish government had already failed to prevent a crowd from burning down the

Wilson's aides had in 1969 come to a similar conclusion, telling him that removing Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom would cause violence and a military intervention by the Republic that would not allow the removal of British troops.

The British so wanted to leave Northern Ireland in 1975, however, that only the catastrophic consequences of doing so prevented it.

Mid-1970s

In February 1974, an IRA time bomb killed 12 people on a coach on the M62 in the West Riding of Yorkshire.[153] Merlyn Rees, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, lifted the proscription against the UVF in April 1974. In December, a month after the Birmingham pub bombings killed 21 people, the IRA declared a ceasefire; this would theoretically last throughout most of the following year. The ceasefire notwithstanding, sectarian killings escalated in 1975, along with internal feuding between rival paramilitary groups. This made 1975 one of the "bloodiest years of the conflict".[74]

On 5 April 1975, Irish republican paramilitary members killed a UDA

On 31 July 1975 at Buskhill, outside Newry, popular Irish cabaret band the Miami Showband was returning home to Dublin after a gig in Banbridge when it was ambushed by gunmen from the UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade wearing British Army uniforms at a bogus military roadside checkpoint on the main A1 road. Three of the bandmembers, two Catholics and a Protestant, were shot dead, while two of the UVF men were killed when the bomb they had loaded onto the band's minibus detonated prematurely. The following January, eleven Protestant workers were gunned down in Kingsmill, South Armagh after having been ordered off their bus by an armed republican gang, which called itself the South Armagh Republican Action Force. This resulted in 10 fatalities, with one man surviving despite being shot 18 times. These killings were reportedly in retaliation to a loyalist double shooting attack against the Reavey and O'Dowd families the previous night.[57][114][133]

The violence continued through the rest of the 1970s. This included a series of attacks in

Late 1970s

By the late 1970s,

In February 1978, the IRA

Successive British Governments, having failed to achieve a political settlement, tried to "normalise" Northern Ireland. Aspects included the removal of internment without trial and the removal of

1980s

In the

In the wake of the hunger strikes, Sinn Féin, which had become the Provisional IRA's political wing,

The IRA's "Long War" was boosted by large donations of arms from

In July 1982, the IRA bombed military ceremonies in London's Hyde Park and Regent's Park, killing four soldiers, seven bandsmen, and seven horses.[170] The INLA was highly active in the early and mid-1980s. In December 1982, it bombed a disco in Ballykelly, County Londonderry, frequented by off-duty British soldiers which killed 11 soldiers and six civilians.[114] In December 1983, the IRA attacked Harrods using a car bomb, killing six people.[171] One of the IRA's most high-profile actions in this period was the Brighton hotel bombing on 12 October 1984, when it set off a 100-pound time bomb in the Grand Brighton Hotel in Brighton, where politicians including Thatcher were staying for the Conservative Party conference. The bomb, which exploded in the early hours of the morning, killed five people, including Conservative MP Sir Anthony Berry, and injured 34 others.[172]

On 28 February 1985 in Newry, nine RUC officers were killed in

In March 1988, three IRA volunteers who were planning a bombing were shot dead by the SAS at a

In September 1989, the IRA used a time bomb to attack the Royal Marine Depot, Deal in Kent, killing 11 bandsmen.[179]

Towards the end of the decade, the British Army tried to soften its public appearance to residents in communities such as Derry in order to improve relations between the local community and the military. Soldiers were told not to use the telescopic sights on their rifles to scan the streets, as civilians believed they were being aimed at. Soldiers were also encouraged to wear berets when manning checkpoints (and later other situations) rather than helmets, which were perceived as militaristic and hostile. The system of complaints was overhauled – if civilians believed they were being harassed or abused by soldiers in the streets or during searches and made a complaint, they would never find out what action (if any) was taken. The new regulations required an officer to visit the complainants house to inform them of the outcome of their complaint.[180]

In the 1980s, loyalist paramilitary groups, including the Ulster Volunteer Force, the Ulster Defence Association, and Ulster Resistance, imported arms and explosives from South Africa.[74] The weapons obtained were divided between the UDA, the UVF, and Ulster Resistance, although some of the weaponry (such as rocket-propelled grenades) were hardly used. In 1987, the Irish People's Liberation Organisation (IPLO), a breakaway faction of the INLA, engaged in a bloody feud against the INLA which weakened the INLA's presence in some areas. By 1992, the IPLO was destroyed by the Provisionals for its involvement in drug dealing, thus ending the feud.[57]

1990s

Escalation in South Armagh

The IRA's South Armagh Brigade had made the countryside village of Crossmaglen their stronghold since the 1970s. The surrounding villages of

In the 1990s, the IRA came up with a new plan to restrict British Army foot patrols near Crossmaglen. They developed two sniper teams to attack British Army and RUC patrols.[182] They usually fired from an improvised armoured car using a .50 BMG calibre M82 sniper rifle. Signs were put up around South Armagh reading "Sniper at Work". The snipers killed a total of nine members of the security forces: seven soldiers and two constables. The last to be killed before the Good Friday Agreement was a British soldier, bombardier Steven Restorick.

The IRA had developed the capacity to attack helicopters in South Armagh and elsewhere since the 1980s,[183] including the 1990 shootdown of a Gazelle flying over the border between counties Tyrone and Monaghan by the East Tyrone Brigade; there were no fatalities in any of those incidents.[184]

Another incident involving British helicopters in South Armagh was the Battle of Newry Road in September 1993.[185] Two other helicopters, a British Army Lynx and a Royal Air Force Puma were shot down by improvised mortar fire in 1994. The IRA set up checkpoints in South Armagh during this period, which were unchallenged by the security forces.[183][186]

Downing Street mortar attack

On 7 February 1991, the IRA attempted to assassinate prime minister John Major and his war cabinet by launching a mortar at 10 Downing Street while they were gathered there to discuss the Gulf War.[187] The mortar bombing caused only four injuries, two of which were to police officers, while Major and the entire war cabinet were unharmed.[187]

First ceasefire

After a prolonged period of background political manoeuvring, during which the 1992 Baltic Exchange and 1993 Bishopsgate bombings occurred in London, both loyalist and republican paramilitary groups declared ceasefires in 1994. The year leading up to the ceasefires included a mass shooting in Castlerock, County Londonderry in which four people were killed. The IRA responded with the Shankill Road bombing in October 1993, which aimed to kill the UDA leadership, but instead killed eight Protestant civilian shoppers and a low-ranking UDA member, as well as one of the perpetrators, who was killed when the bomb detonated prematurely. The UDA responded with attacks in nationalist areas including a mass shooting in Greysteel, in which eight civilians were killed – six Catholics and two Protestants.[57]

On 16 June 1994, just before the ceasefires, the Irish National Liberation Army killed three UVF members in a gun attack on the Shankill Road. In revenge, three days later the UVF killed six civilians in a shooting at a pub in Loughinisland, County Down. The IRA, in the remaining month before its ceasefire, killed four senior loyalist paramilitaries, three from the UDA and one from the UVF. On 31 August 1994, the IRA declared a ceasefire. The loyalist paramilitaries, temporarily united in the "Combined Loyalist Military Command", reciprocated six weeks later. Although these ceasefires failed in the short run, they marked an effective end to large-scale political violence, as they paved the way for the final ceasefires.[57][133]

In 1995, the United States appointed George J. Mitchell as the United States Special Envoy for Northern Ireland. Mitchell was recognised as being more than a token envoy and as representing a President (Bill Clinton) with a deep interest in events.[188] The British and Irish governments agreed that Mitchell would chair an international commission on disarmament of paramilitary groups.[189]

Second ceasefire

On 9 February 1996, less than two years after the declaration of the ceasefire, the IRA revoked it with the

The attack was followed by several more, most notably the

The IRA reinstated their ceasefire in July 1997, as negotiations for the document that became known as the Good Friday Agreement began without Sinn Féin. In September of the same year, Sinn Féin signed

In August 1998, a Real IRA bomb in Omagh killed 29 civilians, the most by a single bomb during the Troubles.[123] This bombing discredited "dissident republicans" and their campaigns in the eyes of many who had previously supported the Provisionals' campaign. They became small groups with little influence, but still capable of violence.[194]

The INLA also declared a ceasefire after the Good Friday Agreement. Since then, most paramilitary violence has been directed at their "own" communities and at other factions within their organisations. The UDA, for example, has feuded with their fellow loyalists the UVF on two occasions since 2000. There have been internal struggles for power between "brigade commanders" and involvement in

Political process

After the ceasefires, talks began between the main political parties in Northern Ireland to establish political agreement. These talks led to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. This Agreement restored self-government to Northern Ireland on the basis of "power-sharing". In 1999, an executive was formed consisting of the four main parties, including Sinn Féin. Other important changes included the reform of the RUC, renamed as the

A security normalisation process also began as part of the treaty, which comprised the progressive closing of redundant British Army barracks, border observation towers, and the withdrawal of all forces taking part in Operation Banner – including the resident battalions of the

The power-sharing Executive and Assembly were suspended in 2002, when unionists withdrew following "Stormontgate", a controversy over allegations of an IRA spy ring operating at Stormont. There were ongoing tensions about the Provisional IRA's failure to disarm fully and sufficiently quickly. IRA decommissioning has since been completed (in September 2005) to the satisfaction of most parties.[197]

A feature of Northern Ireland politics since the Agreement has been eclipsed in electoral terms of parties such as the

Support outside Northern Ireland

Arms importation

Both Republican and Loyalist paramilitaries sought to obtain weapons outside of Northern Ireland in order to achieve their objectives. Irish Republican paramilitaries received the vast majority of external support. Over the years, the Provisional IRA imported arms from external sources such as sympathisers in the Republic of Ireland, Irish diaspora communities within the Anglosphere, mainland Europe, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. The Soviet Union and North Korea supplied the Official IRA with 5,000 weapons,[200] and the INLA received considerable arms from overseas as well.

The IRA's primary external support was from the Republic of Ireland, whose safe haven allowed the group to raise legal and illegal funds, organise and train, and manufacture a large number of firearms and explosives with ease and then smuggled them into Northern Ireland and England.

Loyalist paramilitaries also received support, mainly from Protestant supporters in Canada, England, and Scotland (including members of the Orange Order). From 1979 to 1986, loyalist paramilitaries imported up to 100 machine guns and "as many rifles, grenade launchers, magnum revolvers and hundreds of thousands of rounds of ammunition from Canada."[202] Members of the Grand Orange Lodge of Scotland sent gelignite explosives to UDA and UVF members.[203][204][205] British Army's Force Research Unit (FRU) agent Brian Nelson also secured a large amount of weaponry from the South African government to loyalists.[206]

Funding

Irish Republican and Loyalist militants also received significant funding from groups, individuals, and state actors outside Northern Ireland. From the 1970s to the early 1990s, Libya gave the IRA over $12.5 million in cash (the equivalent of roughly $40 million in 2021).

In the Anglosphere outside Great Britain, Irish Americans, Irish Canadians, Irish Australians, and Irish New Zealanders provided considerable or substantial financial donations to the Republican movement, mostly the Provisionals.[212][213][214] The financial backbone of the Provisional cause in America was the Irish Northern Aid Committee (NORAID), which was estimated to have raised $3.6 million between 1970 and 1991, including for supporting families of dead or imprisoned IRA members, lobbying and propaganda efforts, and sometimes purchasing weapons for the Provisional IRA.[215][216][217][218][219][220] In Australia, officials estimated that by the 1990s, no more than A$20,000 were raised annually for the Provisionals.[221] Canadian supporters raised money to secretly purchase weapons, notably detonators used for Canadian mining sites and smuggled to the IRA.[222][223][224]

However, nearly all or the vast majority of the funding for both Republican and Loyalist paramilitaries came from criminal and business activities within the island of Ireland and Great Britain.[225][226][211][201] The Northern Ireland Affairs Select Committee report of June 2002 stated that:

Historically, the vast majority of paramilitary funds for both Republican and Loyalist groups have been generated within Northern Ireland. The primary reason for this is the relative ease of raising funds within these communities. Sympathy for the cause is greatest within the originating community. Those concerned also have the local knowledge which facilitates crime or the direct intimidation of individuals from whom money is sought. The fact that Northern Ireland remains predominantly a cash economy also encourages a local focus, as it facilitates money laundering and makes it difficult for the law enforcement agencies to trace transactions.[211]

Collusion between security forces and paramilitaries

There were many incidents of

The British Army's locally recruited Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) was almost wholly Protestant.[229][230] Despite recruits being vetted, some loyalist militants managed to enlist, mainly to obtain weapons, training, and information.[231] A 1973 British Government document (uncovered in 2004), Subversion in the UDR, suggested that 5–15% of UDR soldiers then were members of loyalist paramilitaries.[231][232] The report said the UDR was the main source of weapons for those groups,[231] although by 1973, UDR weapons losses had dropped significantly, partly due to stricter controls.[231] In 1977, the Army investigated a UDR battalion based at Girdwood Barracks, Belfast. The investigation found that 70 soldiers had links to the UVF, that thirty soldiers had fraudulently diverted up to £47,000 to the UVF, and that UVF members socialised with soldiers in their mess. Following this, two UDR members were dismissed.[233] The investigation was halted after a senior officer claimed it was harming morale.[233] By 1990, at least 197 UDR soldiers had been convicted of loyalist terrorist offences and other serious crimes, including 19 convicted of murder.[234] This was only a small fraction of those who served in the UDR, but the proportion was higher than the regular British Army, the RUC, and the civilian population.[235]

During the 1970s, the Glenanne gang – a secret alliance of loyalist militants, British soldiers, and RUC officers – carried out a string of gun and bomb attacks against nationalists in an area of Northern Ireland known as the "murder triangle".[236][237] It also carried out some attacks in the Republic, killing about 120 people in total, mostly uninvolved civilians.[238] The Cassel Report investigated 76 murders attributed to the group and found evidence that soldiers and policemen were involved in 74 of those.[239] One member, RUC officer John Weir, claimed his superiors knew of the collusion but allowed it to continue.[240] The Cassel Report also stated some senior officers knew of the crimes but did nothing to prevent, investigate, or punish perpetrators.[239] Attacks attributed to the group include the Dublin and Monaghan bombings (1974), the Miami Showband killings (1975), and the Reavey and O'Dowd killings (1976).[241]

The Stevens Inquiries found that elements of the security forces had used loyalists as "proxies"[242] who, via double-agents and informers, had helped loyalist groups to kill targeted individuals, usually suspected republicans but also civilians both intentionally and otherwise. The inquiries concluded this had intensified and prolonged the conflict.[243][244] The British Army's Force Research Unit (FRU) was the main agency involved.[242] Brian Nelson, the UDA's chief 'intelligence officer', was a FRU agent.[245] Through Nelson, FRU helped loyalists target people for assassination. FRU commanders say they helped loyalists target only suspected or known republican activists and prevented the killing of civilians.[242] The Inquiries found evidence only two lives were saved and that Nelson/FRU was responsible for at least 30 murders and many other attacks, many on civilians.[243] One victim was solicitor Pat Finucane. Nelson also supervised the shipping of weapons to loyalists in 1988.[245] From 1992 to 1994, loyalists were responsible for more deaths than republicans,[246] partly due to FRU involvement.[247][248] Members of the security forces tried to obstruct the Stevens investigation.[244][249]

A

The Smithwick Tribunal concluded that a member of the Garda Síochána (the Republic of Ireland's police force) colluded with the IRA in the killing of two senior RUC officers in 1989.[257][258][259][260] The two officers were ambushed by the IRA near Jonesborough, County Armagh, when returning from a cross-border security conference in Dundalk in the Republic of Ireland.[258]

The Disappeared

During the 1970s and 1980s, republican and loyalist paramilitaries abducted a number of individuals, many alleged to have been informers, who were then secretly killed and buried.[261] Eighteen people – two women and sixteen men – including one British Army officer, were kidnapped and killed during the Troubles. They are referred to informally as "The Disappeared". All but one, Lisa Dorrian, were abducted and killed by republicans. Dorrian is believed to have been abducted by loyalists. The remains of all but four of "The Disappeared" have been recovered and turned over to their families.[262][263][264]

British Army attacks on civilians

British government security forces, including the Military Reaction Force (MRF), carried out what have been described as "extrajudicial killings" of unarmed civilians.[265][266][267] Their victims were often Catholic or suspected Catholic civilians unaffiliated with any paramilitaries, such as the Whiterock Road shooting of two unarmed Catholic civilians by British soldiers on 15 April 1972, and the Andersonstown shooting of seven unarmed Catholic civilians on 12 May that same year.[268] A member of the MRF stated in 1978 that the Army often attempted false flag sectarian attacks, provoking sectarian conflict and "taking the heat off the Army".[269] A former member stated: "[W]e were not there to act like an army unit, we were there to act like a terror group."[270]

Shoot-to-kill allegations

Republicans allege that the security forces operated a shoot-to-kill policy rather than arresting IRA suspects. The security forces denied this and pointed out that six of the eight IRA men killed in the Loughgall ambush in 1987 were heavily armed. On the other hand, the shooting of three unarmed IRA members in Gibraltar by the Special Air Service ten months later appeared to confirm suspicions among republicans and in the British and Irish media of a tacit British shoot-to-kill policy of suspected IRA members.[271]

Parades issue

Inter-communal tensions rise and violence often breaks out during the "marching season" when the Protestant Orange Order parades take place across Northern Ireland. The parades are held to commemorate William of Orange's victory in the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, which secured the Protestant Ascendancy and British rule in Ireland. One particular flashpoint which has caused continuous annual strife is the Garvaghy Road area in Portadown, where an Orange parade from Drumcree Church passes through a mainly nationalist estate off the Garvaghy Road. This parade has now been banned indefinitely, following nationalist riots against the parade and loyalist counter-riots against its banning.

In 1995, 1996, and 1997, there were several weeks of prolonged rioting throughout Northern Ireland over the impasse at Drumcree. A number of people died in this violence, including a Catholic taxi driver killed by the Loyalist Volunteer Force, and three (of four) nominally Catholic brothers (from a mixed-religion family) died when their house in Ballymoney was petrol-bombed.[272][273][274]

Social repercussions

The impact of the Troubles on the ordinary people of Northern Ireland has been compared to that of the Blitz on the people of London.[275] The stress resulting from bomb attacks, street disturbances, security checkpoints, and the constant military presence had the strongest effect on children and young adults.[276] There was also the fear that local paramilitaries instilled in their respective communities with the punishment beatings, "romperings", and the occasional tarring and feathering meted out to individuals for various purported infractions.[277]

In addition to the violence and intimidation, there was chronic unemployment and a severe housing shortage. Many people were rendered homeless as a result of intimidation or having their houses burnt, and urban redevelopment played a role in the social upheaval. Belfast families faced being transferred to new, alien estates when older, decrepit districts such as

According to one historian of the conflict, the stress of the Troubles engendered a breakdown in the previously strict sexual morality of Northern Ireland, resulting in a "confused

Further social issues arising from the Troubles include

Peace lines, which were built in Northern Ireland during the early years of the Troubles, remain in place.[285]

According to a 2022 poll, 69% of Irish nationalists polled believe there was no option but "violent resistance to British rule during the Troubles".[286]

Casualties

According to the Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN), 3,532 people were killed as a result of the conflict between 1969 and 2001.[287] Of these, 3,489 were killed up to 1998.[287] According to the book Lost Lives (2006 edition), 3,720 people were killed as a result of the conflict from 1966 to 2006. Of these, 3,635 were killed up to 1998.[288]

In The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland,

In 2010, it was estimated that 107,000 people in Northern Ireland suffered some physical injury as a result of the conflict. On the basis of data gathered by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, the Victims Commission estimated that the conflict resulted in 500,000 'victims' in Northern Ireland alone. It defines 'victims' are those who are directly affected by 'bereavement', 'physical injury', or 'trauma' as a result of the conflict.[291]

Responsibility

Republican paramilitaries were responsible for some 60% of all deaths, loyalists 30% and British security forces 10%.[39]

| Responsible party | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Republican paramilitary groups | 2,058 | 60% |

| Loyalist paramilitary groups | 1,027 | 30% |

| British security forces | 365 | 10% |

| Persons unknown | 77 | |

| Irish security forces | 5 | |

| Total | 3,532 |

Loyalists killed 48% of the civilian casualties, republicans killed 39%, and the British security forces killed 10%.[292] Most of the Catholic civilians were killed by loyalists, and most of the Protestant civilians were killed by republicans.[293]

Of those killed by republican paramilitaries:[294]

- 1,080 (~52.5%) were members/former members of the British security forces

- 722 (~35.1%) were civilians

- 188 (~9.2%) were members of republican paramilitaries

- 57 (~2.8%) were members of loyalist paramilitaries

- 11 (~0.5%) were members of the Irish security forces

Of those killed by loyalist paramilitaries:[294]

- 878 (~85.5%) were civilians

- 94 (~9.2%) were members of loyalist paramilitaries

- 41 (~4.0%) were members of republican paramilitaries

- 14 (~1.4%) were members of the British security forces

Of those killed by British security forces:[294]

- 188 (~51.5%) were civilians

- 146 (~40.2%) were members of republican paramilitaries

- 18 (~5.0%) were members of loyalist paramilitaries

- 13 (~3.6%) were fellow members of the British security forces

Status

Approximately 52% of the dead were civilians, 32% were members or former members of the British security forces, 11% were members of republican paramilitaries, and 5% were members of loyalist paramilitaries.[39] About 60% of the civilian casualties were Catholics, 30% of the civilians were Protestants, and the rest were from outside Northern Ireland.[295]

About 257 of those killed were children under the age of seventeen, representing 7.2% of the total,[296] while 274 children under the age of eighteen were killed during the conflict.[297]

It has been the subject of dispute whether some individuals were members of paramilitary organisations. Several casualties that were listed as civilians were later claimed by the IRA as their members.

| Status | No. |

|---|---|

| Civilians (inc. Civilian political activists) | 1840 |

| British security force personnel (serving and former members) | 1114 |

TA )

|

757 |

| Royal Ulster Constabulary | 319 |

| Northern Ireland Prison Service | 26 |

English police forces

|

6 |

| Royal Air Force | 4 |

| Royal Navy | 2 |

| Irish security force personnel | 11 |

| Garda Síochána | 9 |

| Irish Army | 1 |

| Irish Prison Service | 1 |

| Republican paramilitaries | 397 |

| Loyalist paramilitaries | 170 |

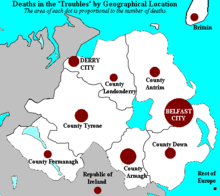

Location

Most killings took place within Northern Ireland, especially in Belfast and County Armagh. Most of the killings in Belfast took place in the west and north of the city. Dublin, London and Birmingham were also affected, albeit to a lesser degree than Northern Ireland itself. Occasionally, the IRA attempted or carried out attacks on British targets in Gibraltar, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands.[301][302]

| Location | No. |

|---|---|

| Belfast | 1,541 |

| West Belfast | 623 |

| North Belfast | 577 |

| South Belfast | 213 |

| East Belfast | 128 |

| County Armagh | 477 |

| County Tyrone | 340 |

| County Down | 243 |

| Derry City | 227 |

| County Antrim | 209 |

| County Londonderry | 123 |

| County Fermanagh | 112 |

| Republic of Ireland | 116 |

| England | 125 |

| Continental Europe | 18 |

Chronological listing

| Year | No. |

|---|---|

| 2001 | 16 |

| 2000 | 19 |

| 1999 | 8 |

| 1998 | 55 |

| 1997 | 22 |

| 1996 | 18 |

| 1995 | 9 |

| 1994 | 64 |

| 1993 | 88 |

| 1992 | 88 |

| 1991 | 97 |

| 1990 | 81 |

| 1989 | 76 |

| 1988 | 104 |

| 1987 | 98 |

| 1986 | 61 |

| 1985 | 57 |

| 1984 | 69 |

| 1983 | 84 |

| 1982 | 111 |

| 1981 | 114 |

| 1980 | 80 |

| 1979 | 121 |

| 1978 | 82 |

| 1977 | 110 |

| 1976 | 297 |

| 1975 | 260 |

| 1974 | 294 |

| 1973 | 255 |

| 1972 | 480 |

| 1971 | 171 |

| 1970 | 26 |

| 1969 | 16 |

Additional statistics

| Incident | No. |

|---|---|

| Injury | 47,541 |

| Shooting incident | 36,923 |

| Armed robbery | 22,539 |

| People charged with paramilitary offences | 19,605 |

| Bombing and attempted bombing | 16,209 |

| Arson | 2,225 |

See also

- 2021 Northern Ireland riots

- Irish Children's Fund

- List of bombings during the Troubles

- List of Gardaí killed in the line of duty

- List of Irish uprisings

- Outline of the Troubles

- Segregation in Northern Ireland

- Timeline of Continuity IRA actions

- Timeline of Irish National Liberation Army actions

- Timeline of Provisional Irish Republican Army actions

- Timeline of Real Irish Republican Army actions

- Timeline of the Troubles

- Timeline of Ulster Defence Association actions

- Timeline of Ulster Volunteer Force actions

In popular culture

- Category:Works about The Troubles (Northern Ireland)

- List of books about the Troubles

- List of The Troubles films

- Murals in Northern Ireland

Similar conflicts

- Algerian War - Algeria, France

- Basque conflict – Basque Country, Spain

- Corsican conflict – Corsica, France

- Sri Lankan Civil War – Sri Lanka

- Years of Lead - Italy

Explanatory notes

- ^ The exact starting date of the Troubles is disputed; the most common dates proposed include the formation of the modern Ulster Volunteer Force in 1966,[1] the civil rights march in Derry on 5 October 1968, the beginning of the 'Battle of the Bogside' on 12 August 1969 or the deployment of British troops on 14 August 1969.

References

- ^ a b "Beginning of the Troubles". Cain.ulst.ac.uk – CAIN. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- ^ Melaugh, Martin (3 February 2006). "Frequently Asked Questions – The Northern Ireland Conflict". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Ulster University. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ OCLC 55962335.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8050-6087-4.

The troubles were over, but the killing continued. Some of the heirs to Ireland's violent traditions refused to give up their inheritance.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-5583-0.

- OCLC 38012191.

- ISBN 978-0-7190-7115-7.

- ^ a b Ministry of Defence Annual Report and Accounts 2006–2007 (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Defence. 23 July 2007. HC 697. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sutton, Malcolm. "Sutton Index of Deaths". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ Melaugh, Martin. "CAIN: Abstracts of Organisations – 'U'". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Ulster University. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ a b Sutton, Malcolm. "Sutton Index of Deaths – Status Summary". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ a b Melaugh, Mertin; Lynn, Brendan; McKenna, F. "Northern Ireland Society – Security and Defence". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Ulster University. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "BBC - History - the Troubles - Violence". BBC History. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Claire (2013). Religion, Identity and Politics in Northern Ireland. Ashgate Publishing. p. 5.

The most popular school of thought on religion is encapsulated in McGarry and O'Leary's Explaining Northern Ireland (1995) and it is echoed by Coulter (1999) and Clayton (1998). The central argument is that religion is an ethnic marker but that it is not generally politically relevant in and of itself. Instead, ethnonationalism lies at the root of the conflict. Hayes and McAllister (1999a) point out that this represents something of an academic consensus.

- ISBN 978-0-631-18349-5.

- ISBN 978-0-521-45933-4.

- ^ Coakley, John. "Ethnic Conflict and the Two-State Solution: The Irish Experience of Partition". Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

... these attitudes are not rooted particularly in religious belief, but rather in underlying ethnonational identity patterns.

- ^ "What You Need to Know About The Troubles". Imperial War Museums. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ Melaugh, Martin; Lynn, Brendan. "Glossary of Terms on Northern Ireland Conflict". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Ulster University. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

The term 'the Troubles' is a euphemism used by people in Ireland for the present conflict. The term has been used before to describe other periods of Irish history. On the CAIN web site the terms 'Northern Ireland conflict' and 'the Troubles', are used interchangeably.

- OCLC 232570935.

The Northern Ireland conflict, known locally as 'the Troubles', endured for three decades and claimed the lives of more than 3,500 people.

- ISBN 978-0-14-100305-4.

- ISBN 978-1-78074-171-0.

- ^ Lesley-Dixon, Kenneth (2018). Northern Ireland: The Troubles: From The Provos to The Det. Pen and Sword Books. p. 13.

- ^ Schaeffer, Robert (1999). Severed States: Dilemmas of Democracy in a Divided World. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 152.

- The News Letter. Johnston Publishing (NI). Archivedfrom the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Peter (26 September 2014). "Who Won The War? Revisiting NI on 20th anniversary of ceasefires". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "Troubles 'not war' motion passed". BBC News. 18 February 2008. Archived from the original on 25 February 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-312-23949-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-5583-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84631-065-2.

- ISBN 0-275-97378-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-517753-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8132-1366-8.

- ^ Jenkins, Richard (1997). Rethinking Ethnicity: Arguments and Explorations. SAGE Publications. p. 120.

It should, I think, be apparent that the Northern Irish conflict is not a religious conflict ... Although religion has a place – and indeed an important one – in the repertoire of conflict in Northern Ireland, the majority of participants see the situation as primarily concerned with matters of politics and nationalism, not religion. And there is no reason to disagree with them.

- ISBN 0-415-15477-4..

- ISBN 0-7453-1413-9..

- ^ "The Troubles: How 1969 violence led to Army's longest campaign". BBC News. 14 August 2019. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019.

- ^ Operation Banner, alphahistory.com Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Sutton Index of Deaths: Summary of Organisation responsible". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Ulster University. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Moriarty, Gerry (5 August 2019). "Northern Ireland: Eighty-one 'punishment attacks' in past year". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "South East Antrim UDA: 'A criminal cartel wrapped in a flag'". BBC News. 21 March 2021.

- ^ "Drugs and cash seized in raids linked to South East Antrim UDA". Belfast Telegraph.

- ^ Earwin, Alan (25 March 2021). "Surveillance recorded 'South East Antrim UDA drugs conversation', court is told". News Letter. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ "Police seize suspected drugs in operation linked to the South East Antrim UDA". 14 October 2022.

- ^ "Drugs seized in searches linked to South East Antrim UDA". BBC News. 4 September 2018.

- ^ "Loyalist terror groups UVF and UDA on collision course over 'drug deal turned sour'". 16 May 2023.

- ^ "Draft List of Deaths Related to the Conflict (2003–present)". Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ISBN 978-1-84603-023-9. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8132-1366-8. Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ISBN 978-0333753460.

- ISBN 978-0754649908.

- ^ Ryan Hackney and Amy Blackwell Hackney. The Everything Irish History & Heritage Book (2004). p. 200

- ^ "Out of trouble: How diplomacy brought peace to Northern Ireland". CNN. 17 March 2008. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ a b Frank Wright. Ulster: Two Lands, One Soil, 1996, p. 17.

- ^ "Profile: The Orange Order". BBC News. 4 July 2001. Archived from the original on 29 June 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-330-42759-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Coogan, Tim Pat (2002). The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal and the Search for Peace. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Parliamentary debate Archived 10 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine: "The British government agree that it is for the people of the island of Ireland alone, by agreement between the two parts respectively, to exercise their right of self-determination on the basis of consent, freely and concurrently given, North and South, to bring about a united Ireland, if that is their wish."

- OCLC 1001466881.

- ISBN 978-0-563-20787-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-517753-4. Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ "CRESC Working Paper Series : Working Paper No. 122" (PDF). Cresc.ac.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ Meehan, Niall (1 January 1970). "Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogroms G.B. Kenna 1922 | Niall Meehan". Academia.edu. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ "History Ireland". History Ireland. 4 March 2013. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-19-925258-9.

- ^ Laura K. Dohonue. "Regulating Northern Ireland: The Special Powers Acts, 1922–1972", The Historical Journal (1998), vol 41, no. 4.

- ^ Feldman, Allen (1991). Formations of Violence: The Narrative of the Body and Political Terror in Northern Ireland (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 40–41.

- ^ McKittrick, David; McVea, David (2012). Making Sense of the Troubles: A History of the Northern Ireland. London: Viking. pp. 8–10.

- ^ "Revisiting the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Movement: 1968–69 – The Irish Story". Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Chronology of Key Events in Irish History: 1800 to 1967 Archived 3 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine, cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Loyalists, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Andrew Boyd. Holy War in Belfast. "Chapter 11: The Tricolour Riots" Archived 27 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Anvil Books, 1969; reproduced here Archived 30 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Hugh Jordan. Milestones in Murder: Defining moments in Ulster's terror war. Random House, 2011. Chapter 3.

- ^ a b c d e f Peter Taylor. Loyalists (1990). London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. pp. 41–44, 125, 143, 163, 188–90

- ^ "Proscribed terrorist groups or organisations". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "We Shall Overcome ... The History of the Struggle for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland 1968–1978". cain.ulst.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 31 May 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Northern Ireland: The Plain Truth (second edition) Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Campaign for Social Justice in Northern Ireland, 15 June 1969. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-582-42400-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4058-2411-8.

- ISBN 978-0-10-400766-2. Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ English (2003), pp. 91, 94, 98

- ^ Lord Cameron, Disturbances in Northern Ireland: Report of the Commission appointed by the Governor of Northern Ireland (Belfast, 1969). Chapter 16 Archived 1 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Quote: "While there is evidence that members of the I.R.A. are active in the organisation, there is no sign that they are in any sense dominant or in a position to control or direct policy of the Civil Rights Association."

- ^ M. L. R. Smith (2002). Fighting for Ireland?: The Military Strategy of the Irish Republican Movement. Routledge. p. 81.

Republicans were instrumental in setting up NICRA itself, though they did not control the Association and remained a minority faction within it.

- ^ Bob Purdie. "Chapter 4: The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association". Politics in the Streets: The origins of the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland. Blackstaff Press.

There is also clear evidence that the republicans were not actually in control of NICRA in the period up to and including the 5 October march.

- ^ a b c d Chronology of the Conflict: 1968 Archived 6 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ "Sixteen of us in one small house" (Audio) (Interview). Interviewed by Proinsias Ó Conluain. RTÉ Archives. 27 August 1969. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ "Caledon Housing Protest". Campaign for Civil Rights. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ "Submission to the Independent Commission into Policing". Serve.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ a b c Martin Melaugh. "The Derry March: Main events of the day". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Ulster University. Archived from the original on 23 November 2007. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-85640-323-1.

- ^ a b Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack. Burntollet Archived 20 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. L.R.S. Publishers, 1969; reproduced on CAIN. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ISBN 0-7475-3818-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7475-5806-4.

- ^ a b c d e "Chronology of the Conflict: 1969". cain.ulst.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Jim Cusack & Henry McDonald. UVF. Poolbeg, 1997. p. 28

- ISBN 978-0-7475-4519-4.

- ^ Police Ombudsman statement on Devenny investigation Archived 6 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 October 2001.

- ^ Russell Stetler. Extract from The Battle of Bogside (1970) Archived 20 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine, cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^

- ISBN 978-1-84724-195-5.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link

- Telefís Éireann. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

The Irish Government can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured and perhaps worse.

- The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal and the Search for Peace, p. 89

- ISBN 978-0-521-46944-9.

- ^ Downey, James (2 January 2001). "Army on Armageddon alert". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-9546284-2-0.

- ISBN 978-1-84018-504-1.

- ISBN 0-9514229-4-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84018-504-1.

- ^ The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal and the Search for Peace, p. 91

- ISBN 978-0-7391-7694-8.

- ^ "Conclusions of a meeting of the Joint Security Committee held on Tuesday, 9th September, 1969, at Stormont Castle [PRONI Public Records HA/32/3/2]" (PDF). CAIN. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ISBN 0-9514837-0-6. Archivedfrom the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ "Interfaces". Peacewall Archive. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ David McKittrick. Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles. Random House, 2001. p. 42

- ISBN 978-0-19-517753-4.

- ^ "McGurk's bar bombing – A dark night in the darkest times". BBC News. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Sutton, Malcolm. "Sutton Index of Deaths". CAIN – Conflict Archive on the Internet. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-552-13337-1.

- ^ English (2003), pp. 134–135

- ISBN 978-1-904684-18-3.

- ISBN 978-0-7546-4756-0.

- ^ "10 people shot dead in Ballymurphy were innocent, inquest finds". The Guardian. 11 May 2021. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Melaugh, Dr Martin. "CAIN: Events: 'Bloody Sunday' – Names of Dead and Injured". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-7171-3085-6. Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ^ Melaugh, Dr Martin. "CAIN: [Widgery Report] Report of the Tribunal appointed to inquire into events on Sunday 30 January 1972". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Archived from the original on 23 September 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Melaugh, Dr Martin. "CAIN: Violence: List of Significant Violent Incidents". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Archived from the original on 2 May 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-84115-316-2.

- ^ "Internment – Summary of Main Events". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-521-83351-6.

- ISBN 978-0-702-11812-8.

- ISBN 978-0-792-31283-3.

- ISBN 0-14-101041-X.

- ISBN 978-0-7475-3818-9.

- ^ a b English (2003), p. 137

- ISBN 978-0-86278-425-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-56000-901-6.

- ^ "Bloody Friday: What happened". BBC News. 16 July 2002. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ Sutton, Malcolm. "Index of deaths from the conflict in Ireland: 1972". CAIN archive. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-84018-504-1.

- ^ "CAIN: Victims: Memorials: Claudy Bomb Memorial". cain.ulster.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "New investigation into Claudy bombing". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "IRA bomb in Claudy was indefensible, says Martin McGuinness". The Guardian. 31 July 2012. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7486-4696-8.

- ISBN 978-0-14-101041-0.

- ^ "1972: Official IRA declares ceasefire". BBC News. 30 May 1981. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- S2CID 143467248.

- ^ a b c Melaugh, Dr Martin. "CAIN: Chronology of the Conflict 1972". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ Keeping Secrets, London Review of Books, April 1987.

- ^ "UK urged to Release Dublin and Monaghan Bombing Files". The Irish Times. 17 May 2017. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ a b Donnelly, Rachel (3 January 2000). "Wilson weighed up direct rule in North". The Irish Times. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Bourke, Richard (3 January 2005). "Wilson clearly wanted to disengage from the North". The Irish Times. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ doi:10.3318/ISIA.2006.17.1.141. Archived from the original(PDF) on 26 September 2007.

- ^ "Every Briton Now a Target for Death". The Sydney Morning Herald. 1 December 1974. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Wilson had NI 'doomsday' plan". BBC News. 11 September 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ "M62 bomb blast memorial unveiled". 4 February 2009. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ "Man released over 1975 Shankill pub bombing". BBC News. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "Mountainview Bar Plaque". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Ulster University. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Mullin, John (10 April 1999). "Balcombe Street Gang to be freed". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "CAIN: Events: IRA Truce – 9 Feb 1975 to 23 Jan 1976 – A Chronology of Main Events". cain.ulster.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-7475-3818-9.

- ISBN 0-14-101041-X.

- ISBN 978-0-74531-295-8.

- ^ "1978 La Mon bombing commemorated in Belfast". RTÉ.ie. 16 February 2003. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "1979: Soldiers die in Warrenpoint massacre". BBC News. 27 August 1979. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ a b "The Hunger Strike of 1981 – A Chronology of Main Events". CAIN. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- ^ English (2003), p. 200

- ISBN 1-57500-061-X.

- ISBN 978-0-330-34648-1.

- ISBN 1-56000-901-2.

- JSTOR 27041321.

- ^ Cusack & McDonald, pp. 198–199

- ^ "1982: IRA bombs cause carnage in London". BBC News. 20 July 1982. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Harrods bomb blast kills six people, 1983". Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ "On This Day: 12 October 1984". BBC News. 12 October 2000. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ a b "RUC and IRA chiefs' lives feature in national biography". BBC News. 5 January 2012. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "CAIN: Victims: Memorials: Search Results Page". cain.ulster.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ a b "IRA men shot dead at Loughgall had been under surveillance for weeks, court told". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "Northern Ireland | IRA bomb victim buried". BBC News. 30 December 2000. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ McKittrick, David. Lost Lives: The stories of the men, women and children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland Troubles. Random House, 2001. pp. 1094–1099

- ^ On this day: Loyalist killer Michael Stone freed from Maze Archived 7 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC

- ^ "Deal bombing 25th anniversary remembered". BBC News. 13 July 2014. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Moloney, Ed. A Secret History of the IRA. Penguin UK, 2007.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ "A Chronology of the Conflict, 1978". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ General Sir Michael Jackson. Operation Banner: An Analysis of Military Operations in Northern Ireland (2006) Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, MoD, Army Code 71842. Chapter 2, p. 16, item 247.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-340-71737-0.

- ^ "Soldiers hurt in IRA attack on helicopter". Glasgow Herald. 12 February 1990. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-7553-6391-9.

- ^ Department of the Official Report (Hansard), House of Commons, Westminster (8 June 1993). "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 8 Jun 1993". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Terror plot reminiscent of IRA attacks". 7 December 2017.

- ^ "US policy and Northern Ireland". BBC News. 8 April 2003. Archived from the original on 22 May 2004. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "A Break in the Irish Impasse". The New York Times. 30 November 1995. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ "BBC On This Day 1996: Docklands bomb ends IRA ceasefire". BBC News. 10 February 1996. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2016.