The Wood Nymph

| The Wood Nymph | |

|---|---|

Helsinki Philharmonic Society |

The Wood Nymph (

The Wood Nymph was performed three more times that decade, then, at the composer's request, once more in 1936. Never published, the ballade had been thought to be comparable to insubstantial works and juvenilia which Sibelius had suppressed until the Finnish musicologist Kari Kilpeläinen 'rediscovered' the manuscript in the University of Helsinki archives, "[catching] Finland, and the musical world, by surprise".[4] Osmo Vänskä and the Lahti Symphony Orchestra gave the ballade its modern-day 'premiere' on 9 February 1996. Although the score had been effectively 'lost' for sixty years, its thematic material had been known in abridged form via a melodrama for narrator, piano, two horns, and strings. Sibelius probably arranged the melodrama from the tone poem, although he claimed the opposite. Some critics, while admitting the beauty of the musical ideas, have faulted Sibelius for over-reliance on the source material's narrative and lack of the rigorously unified structure that characterized his later output, whereas others, such as Veijo Murtomäki, have hailed it as a "masterpiece"[5] worthy of ranking amongst Sibelius's greatest orchestral works.

Composition

Sibelius admired Rydberg and often set his poetry to music, including the melodrama Snöfrid, Op. 29, and the War Song of Tyrtaeus.[6][7][8] The poem Skogsrået was first published in 1882, and in 1883 Sibelius's future friend, the artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela, illustrated it. In 1888 or 1889, about the time the two met, Sibelius first set Skogsrået for voice and piano. This setting is musically unrelated to Sibelius's 1894–95 treatment.[b][10][3]

In 1894, although Sibelius was a national figure in Finland and had completed major works like Kullervo and the Karelia Suite, he was still struggling to break free of Wagnerian models and develop a truly individual style.[3] The origin of the tone poem remains obscure but The Wood Nymph may well have gradually evolved out of music for a verismo opera that Sibelius had planned but never realized. The libretto, as related in a letter from Sibelius dated 28 July 1894, tells the story of a young, engaged student who, while travelling abroad, meets and is attracted by an exotic dancer. Upon his return, the student describes the dance and dancer so vividly that his fiancée concludes he has been unfaithful; the opera ends with a funeral procession for the student's fiancée (the letter is unclear as to her cause of death). Furthermore, in a letter from 10 August 1894, Sibelius informs his wife, Aino, of a new composition "in the style of a march". Murtomäki argues that Sibelius readily adapted his previous musical ideas to the plot of Skogsrået: the march became Björn's theme from the first section of The Wood Nymph, the protagonist "tak[ing] himself off (abroad)" became the frenetic chase of the second, the unfaithfulness with the dancer became the seduction by the evil skogsrå in the third, and the opera's funeral procession became the despair of Björn in the finale.[11]

While both tone poem and melodrama would emerge from this material, it is not clear which musical form Sibelius initially used to tackle Rydberg's poem. In the 1930s, the composer claimed he had first composed the melodrama (premiered on 9 March 1895 at a lottery ball benefiting the Finnish Theatre where it was narrated by Axel Ahlberg), only to realize subsequently that "the material would allow a more extensive treatment" as a symphonic poem. Scholars, however, have disputed this chronology, arguing that, given the premiere of the tone poem a mere month later, it is "improbable, if not totally impossible" that Sibelius could have expanded the melodrama so quickly. He probably "compressed" the earlier tone poem, eliminating bridges and repetitions, to produce the streamlined melodrama.[12][11][13] The manuscript of the melodrama has far fewer corrections than the manuscript of the tone poem, which supports this view.[3] Sibelius also arranged the conclusion for solo piano.[c][10]

Performance history

The tone poem premiered on 17 April 1895, at the Great Hall of the

After 1936, The Wood Nymph again disappeared from the repertoire. Throughout his career, Sibelius was troubled with creative 'blocks' and bouts of depression. This led him to commit score to the flames when he felt unable to revise them to the level he demanded. This was the fate most notoriously of the Symphony No. 8, but also of many works from the 1880s and 1890s.[15][16] He did not, however, destroy The Wood Nymph. The ballade lay neglected amongst the more than 10,000 pages of papers and scores which the composer's family had deposited in 1982 at the University of Helsinki Library archive.[5] The work was 'rediscovered' by the manuscript expert Kari Kilpeläinen; its subsequent inspection by Fabian Dahlström "caught Finland, and the musical world, by surprise": the tone poem, 22 minutes in length and scored for full orchestra, was far more than the melodrama "recast without the speaker" many in the Sibelius establishment had assumed it to be.[4] The Wood Nymph received its modern-day 'world premiere' on 9 February 1996 by the Lahti Symphony Orchestra, with Osmo Vänskä conducting. Vänskä had received permission from Sibelius's family to perform the work.[17] Out of necessity, Vänskä supplemented the manuscript—full of edits and, thus, "very difficult to read" in isolation—with notes from the 1936 performance.[18] In 2006, Breitkopf & Härtel published the first edition of The Wood Nymph.[1]

Orchestration

Structure

In 1893, Sibelius had expressed his belief in the necessity of poetic motivation in music in a letter to the poet

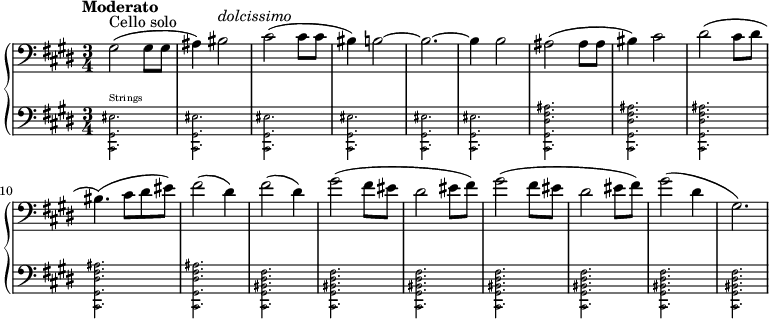

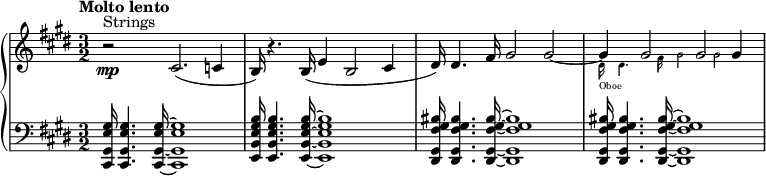

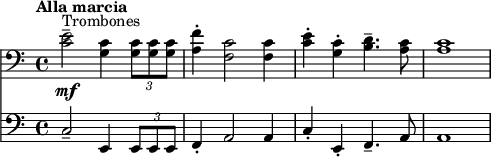

- Alla marcia

- Vivace assai—Molto vivace

- Moderato

- Molto lento

First section

Björn, "a tall and handsome lad", is announced by a heroic brass fanfare. His strength and good looks have aroused "the cunning spirits", and on his way to a feast one summer evening, he is entranced by the "singing" woods. The opening music, "breezy" and triumphant in C major, recalls the Karelia Overture, Op. 10 (not to be confused with the Karelia Suite, Op. 11) which Sibelius had written in 1893,[20] and betrays no sign of Björn's impending fate. Björn's theme is recapitulated at the end of the second section.

| Original Swedish | English translation[22] |

|---|---|

Han Björn var en stor och fager sven |

Björn was a tall and handsome lad |

Second section

Björn "willingly but under duress", plunges deep into the magical Nordic forest and is enchanted by evil, mischievous dwarves, who "knit a web of moonbeams" and "hoarsely laugh at their prisoner". Considered by some critics to be the tone poem's most striking section,[10][23] the "proto-minimalist" music in A minor is at once hypnotic and delightfully propulsive: Sibelius repeats and reworks the same short motif (belonging initially to the clarinets) into a rich woodwind tapestry, quickening the tempo and adding off-beat horns and pulsating trombones, to produce what Murtomäki has described as a "modal-diatonic sound field".[24]

| Original Swedish | English translation[22] |

|---|---|

Han går, han lyder det mörka bud, |

He walks on, obeys the dark command, |

Third section

Björn encounters and is seduced by a beautiful wood nymph (

| Original Swedish | English translation[22] |

|---|---|

Nu tystnar brått den susande vind, |

Now the sighing wind abates, |

Fourth section

Having lost any hope of earthly happiness (in Swedish folklore, a man who succumbed to the skogsrå was doomed to lose his soul),[10] Björn despairs. The music mutates from the erotic C-sharp major to a dark and mournful 'funeral march' in C-sharp minor.[27] As the undulating, "aching" violin theme crashes against the brass, Björn is left with "inconsolable grief", obsessed with the memory of the skogsrå. "Hardly ever has music been written," wrote the music critic of the newspaper Uusi Suometar following the 1899 performance, "which would more clearly describe remorse."[28]

| Original Swedish | English translation[22] |

|---|---|

Men den, vars hjärta ett skogsrå stjäl, |

But he whose heart a wood nymph stole, |

Reception

Although well received upon its premiere, critical opinion as to the merit of The Wood Nymph has varied. Following the 1895 premiere,

As a whole, Skogsrået is not a highly unified organism like Sibelius’s subsequent large orchestral works: the four Lemminkäinen legends and the first two symphonies...The formal problem is that the links are, for the most part, missing; Sibelius simply juxtaposes different formal sections without connective elements smoothing over the junctures. In view of his later mastery of the "art of transition," achieved by subtly overlapping different textures and tempos, in Skogsrået Sibelius is still at the beginning of his development.[30]

Guy Rickards, concurring that The Wood Nymph "never quite escapes a dependence on the verses", has echoed Tawaststjerna in wondering what might have been had Sibelius returned in his maturity to The Wood Nymph, as with

Analysis

Autobiographical details

A few musicologists have speculated that The Wood Nymph is potentially autobiographical. Murtomäki, most notably, has argued that the tone poem's depiction of "a fatal sexual conjunction" between Björn and the skogsrå is a possible allusion to the composer's own youthful indiscretions. "The strong autobiographical element in Skogsrået is unmistakable", Murtomäki has written, adding that in the ballade, "Sibelius probably confesses an affair to Aino".[35] For Murtomäki, the balladic nature of The Wood Nymph is key, as in the genre "it was expected that the singer/storyteller/composer should reveal himself". At the time, it was common for the first sexual partners of men of Sibelius's class to be prostitutes. Murtomäki says that "In their concealed or "unofficial" sexual life, they experienced a certain type of female sexual adventurousness that their wives could not easily match." He hypothesizes that The Wood Nymph and other contemporaneous compositions were Sibelius's method of dealing with the emotional consequences of this and his guilt towards his wife Aino.[36]

With its focus on sexual fantasy, The Wood Nymph differs sharply from the Rydberg poem Snöfrid which Sibelius set in 1900. In Snöfrid, Gunnar, the patriotic hero, resists a water nymph's sensuous "embrace" to instead "fight the hopeless fight" for his country and "die nameless". The contrast between Björn and Gunnar, Murtomäki argues, reflects Sibelius's own personal transformation: crowned a "national hero" following the 1899 premiere of the Symphony No. 1, Sibelius wished to demonstrate that he had "outgrown his early adventurism" and learned to place country before "libertine" excess.[37] Murtomäki's conclusion, however, is not universally accepted. David Fanning, in his review of the edited volume in which Murtomäki's essay appears, has savaged as "dubious" and "tendentious" such autobiographical speculations. Per Fanning: "For Murtomäki every half-diminished chord seems to be a Tristan chord, with all the symbolic baggage that entails...Such half-baked hermeneutics baffle and alienate...enthusiasm has occasionally been allowed to run riot".[38]

Lack of publication

Why Sibelius should have failed to prepare The Wood Nymph for publication is a question that has perplexed scholars. On the advice of Ferruccio Busoni, Sibelius in 1895 offered The Wood Nymph to the Russian music publisher Mitrofan Belyayev but it was not published.[1] Murtomäki has suggested that Sibelius, despite having been fond of The Wood Nymph, was "unsure about the true value" of his output from the 1890s,[39] an ambivalence that is perhaps best illustrated by the piecemeal publication history of, and multiple revisions to, the four Lemminkäinen legends (appearing in the composer's 1911 diary under a list of works to be rewritten, The Wood Nymph, too, seems to have been scheduled by Sibelius for a reexamination, albeit one that never came to pass).[12] Scholars have offered a number of explanations as to why Sibelius may have "turned his back" on his early compositions. Perhaps, as master, he looked back on the works of his youth as technically "inferior" to his mature output; or, as evolving artist, he sought distance from passionate, nationalistic exclamations as he developed his own, unique musical style and aimed to transition from "local hero" to "international composer"; or, as elder statesman, he feared he might have "revealed himself too much" in early "confessional" works, such as En saga, Lemminkäinen and the Maidens of the Island, and The Wood Nymph.[40] In the absence of any new information from Sibelius's papers, however, the reason why The Wood Nymph was never published ultimately "appears doomed to remain a subject of speculation".[12]

Discography

Even after the wave of publicity that followed its reemergence, The Wood Nymph remains rarely recorded compared to other early Sibelius works. It received its world premiere in 1996 under the BIS label with Osmo Vänskä leading the Lahti Symphony Orchestra. Some musical material was unavailable until the publication of the Breitkopf & Härtel JSW critical edition in 2006 and was thus not included on prior recordings. The 1888 version for voice and piano has been recorded by Anne Sofie von Otter. Erik Tawaststjerna also recorded the piano solo version together with the rest of Sibelius's piano transcriptions. The 1996 Vänskä recording also included the first recording of the melodrama, narrated by Lasse Pöysti.

| Conductor | Orchestra | Recorded | Duration | Available on |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osmo Vänskä | Lahti Symphony Orchestra | 1996 | 21:36 | BIS (BIS-CD-815) |

| Shuntaro Sato | Kuopio Symphony Orchestra | 2003 | 22:22 | Finlandia (0927-49598-2) |

| Osmo Vänskä | Lahti Symphony Orchestra | 2006 | 21:37 | BIS (BIS-SACD-1745) |

| Douglas Bostock | Gothenburg-Aarhus Philharmonic Orchestra | 2007 | 21:05 | Classico (CLASSCD733) |

| John Storgårds | Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra | 2010 | 24:05 | Ondine (ODE 1147-2) |

Notes

- ^ During the tone poem's long period of obscurity, the dramatic monologue was listed as 'Op.15' in the Sibelius worklists and the tone poem was omitted.[3]

- ^ In the collected works, it is catalogued as JS 171.[9]

- ^ With the title Ur "Skogsrået" (English: From "Skogsrået").[9]

- ^ The melodrama was performed in Tampere in 1898 and in Joensuu in 1911.[12]

- ^ Tawaststjerna, incidentally, must have been one of the very few to examine the manuscript of the orchestral version during its long obscurity.

References

- ^ a b c Wicklund 2015, p. viii.

- ^ a b Dahlström 2003, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e Wicklund 2015, p. vi.

- ^ a b c Anderson 1996, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Murtomäki 2001, p. 95.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 139.

- ^ Mäkelä 2007, p. 311.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1976, p. 200.

- ^ a b Goss 2009, p. 543.

- ^ a b c d Goss 2009, p. 202.

- ^ a b Murtomäki 2001, p. 102–103.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kurki 1999.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 97.

- ^ Wicklund 2015, p. vii.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 345.

- ^ Howell 2006, p. 32.

- ^ Tumelty 1996, p. 13.

- ^ a b Grimley 2004, p. 240.

- ^ Murtomäki 2001, p. 102.

- ^ a b c d Grimley 2004, p. 100.

- ^ Goss 2009, p. 204-206.

- ^ a b c d Rydberg 1882.

- ^ a b Grimley 2004, p. 101.

- ^ a b c Sirén 2005.

- ^ Kilinski 2013, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Goss 2009, p. 204.

- ^ Murtomäki 2001, p. 119.

- ^ Murtomäki 2001, p. 126.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1976, p. 163.

- ^ Murtomäki 2001, p. 123.

- ^ Rickards 1996, pp. 43–45.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 98.

- ^ Murtomäki 2001, pp. 101–102, 119.

- ^ Murtomäki 2001, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Murtomäki 2001, p. 127.

- ^ Murtomäki 2001, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Murtomäki 2001, pp. 99, 137–138.

- ^ Fanning 2001, pp. 663–666.

- ^ Murtomäki 2001, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Murtomäki 2001, pp. 97, 99.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Martin (1996). "Sibelius's 'The Wood Nymph'". JSTOR 944466.

- Barnett, Andrew (2007). Sibelius. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11159-0.

- ISBN 3-7651-0333-0.

- Fanning, David (2001). "Review of Sibelius Studies". JSTOR 3526300.

- Goss, Glenda Dawn (2009). Sibelius: A Composer's Life and the Awakening of Finland. London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-30479-3.

- Grimley, Daniel M. (2004). "The Tone Poems: Genre, Landscape and Structural Perspective". In Grimley, Daniel M. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Sibelius. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89460-9.

- Howell, Tim (2006). After Sibelius: Studies in Finnish Music. Ashgate Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7546-5177-2.

- Kilinski, Karl (2013). Greek Myth and Western Art: The Presence of the Past. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01332-2.

- Kurki, Eija (1999). "The Continuing Adventures of Sibelius's Wood-Nymphs: The Story So Far". Music Finland. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- Mäkelä, Tomi (2007). Jean Sibelius. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84383-688-9.

- Murtomäki, Veijo (2001). "Sibelius's symphonic ballad Skogsrået". In ISBN 978-0-521-62416-9.

- Rickards, Guy (1996). "Review". JSTOR 944443.

- Rydberg, Viktor (1882). "Skogsrået" (PDF). Naxos Music Library. pp. 114–115. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- Sirén, Vesa (2005). "Other Orchestral Works: Skogsrået (The Wood Nymph)". Sibelius.fi. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-520-03014-5.

- Tumelty, Michael (February 3, 1996). "The Key to Settling an Old Score". The Herald. Glasgow. p. 13.

- Wicklund, Tuija, ed. (2015). Sibelius: Skogsraet – The Wood Nymph Op. 15. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel. ISMN979-0-004-21374-2.

![\relative c'{ \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"clarinet" \tempo "Vivace assai" \clef treble a8[^"Clarinet" a8 c8. b16] a8[ a8 r8 a8]~ a8[ a8 c8. d16] e8[ a,8 r8 a8]~ a8[ a8 c8. b16] a8[ a8 r8 a8]( fis8[) fis8 gis8 a8] b8[ a8] r8}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/c/y/cy3anjngyeved70v1znj9v1pd31uilg/cy3anjng.png)