Theorbo

| |

| Other names | chitarrone, theorbo lute; fr: téorbe, théorbe, tuorbe; de: Theorbe; it: tiorba, tuorba[1] |

|---|---|

| Classification |

|

| Related instruments | |

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The theorbo is a

The theorbo is related to the liuto attiorbato, the French théorbe des pièces, the archlute, the German baroque lute, and the angélique (or angelica). A theorbo differs from a regular lute in its so-called re-entrant tuning in which the first two strings are tuned an octave lower. The theorbo was used during the Baroque music era (1600–1750) to play basso continuo accompaniment parts (as part of the basso continuo group, which often included harpsichord, pipe organ and bass instruments), and also as a solo instrument. It has a range similar to that of cello.

Origin and development

Theorbos were developed during the late sixteenth century in Italy, inspired by the demand for extended bass range instruments for use in the then-newly developed musical style of opera developed by the

Although the words chitarrone and tiorba were both used to describe the instrument, they have different organological and etymological origins; chitarrone being in Italian an augmentation of (and literally meaning large) chitarra – Italian for guitar. The round-backed chitarra was still in use, often referred to as chitarra Italiana to distinguish it from chitarra alla spagnola in its new flat-backed Spanish incarnation. The etymology of tiorba is still obscure; it is hypothesized the origin may be in Slavic or Turkish torba, meaning 'bag' or 'turban'.

According to

The most prominent early composers and players in Italy were

Tuning and strings

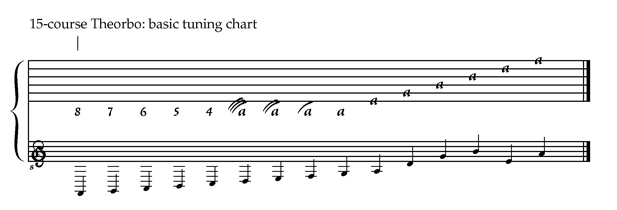

The

This is theorbo tuning in A. Modern theorbo players usually play 14-course (string) instruments (lowest course is G). Some players have used a theorbo tuned a whole step lower in G. Most of the solo repertoire is in the A tuning. The "re-entrant tuning" created new possibilities for

Regional differences

Italy

The theorbo was developed in Italy, and so has a rich legacy in Italian music as both a solo and continuo instrument. Caccini comments in Le nuove musiche (1602) that the theorbo is perfectly suited for accompanying the voice as it can give a very full support without being obscured by the vocalist, indicating the beginning of an Italian tradition of monodic songs accompanied by theorbo. Italians called the theorbo's diapasons its “special excellence”.[3] Italians viewed the theorbo as an easier alternative to the lute since the general attractiveness of its sound quality can cover over indifferent playing and lazy voice leading.[3]

England

The Italian theorbo first came to England at the beginning of the seventeenth century, but an alternate design based on the English two-headed lute, designed by Jaques Gaultier, soon became more popular.[3] English theorbos were generally tuned in G and double strung throughout, with only the first course in reentrant tuning. Theorbos tuned in G were much better suited to flat keys, and so many English songs or consort pieces that involved theorbo were written in flat keys that would be very difficult to play on a theorbo in A.[3] By the eighteenth century, the theorbo had fallen out of fashion in England due to its large size and low pitch. It was replaced by the archlute.[3]

France

The first mention of a theorbo in France was in 1637, and by the 1660s it had replaced the 10-course lute as the most popular accompanying instrument.[3] The theorbo was a very important continuo instrument in the French court and multiple French theorbo continuo tutors (method books) were published by Delair (1690), Campion (1716 and 1730), Bartolotti (1669), Fleury (1660), and Grenerin (1670).[3] French theorbos had up to eight stopped strings and were often somewhat smaller and quieter than Italian theorbos. They were a standard scale length of 76 cm, which made them smaller than Italian instruments, which ranged from 85–95 cm.[3]

Germany

German theorbos would also today be called swan-necked Baroque lutes; seventeenth-century German theorbists played single-strung instruments in the Italian tuning transposed down a whole step, but eighteenth-century players switched to double-strung instruments in the “d-minor” tuning used in French and German Baroque lute music so as to not have to rethink their chord shapes when playing theorbo. These instruments came to be referred to as theorbo-lutes.[4] Baron remarks that “the lute, because of its delicacy, serves well in trios or other chamber music with few participants. The theorbo, because of its power, serves best in groups of thirty to forty musicians, as in churches and operas.”[4] Theorbo-lutes would likely have been used alongside Italian theorbos and archlutes in continuo settings due to the presence of Italian musicians in German courts and also for the purpose of using instruments that were appropriate for whatever key the music was in.[3]

Ukraine, Poland and Russia

The theorbo came to Ukraine ca. 1700 and it was upgraded with treble strings (known as prystrunky). This instrument was called a torban.[5] The Torban was manufactured and used mainly in Ukraine, but also occasionally encountered in neighbouring Poland and Russia.[6]

Technique

The theorbo is played much like the lute, with the left hand pressing down on the fingerboard to vary the resonating length of the strings (thus playing different notes and making chords, basslines and melodies playable) while the right fingertips pluck the strings. The most significant differences between theorbo and lute technique are that theorbo is played with the right thumb outside the hand, as opposed to Renaissance lute which is played with the thumb under the hand. Additionally, the right hand thumb is entirely responsible for playing the bass diapasons and rarely comes up onto the top courses. Most theorbists play with the flesh of their fingers on the right hand, although there is some historical precedent from Piccinini, Mace, and Weiss to use nails. Fingernails can be more effective on a theorbo than on a lute due to its single-strung courses, and the use of nails is most often suggested in the context of ensemble playing where tone quality becomes subservient to volume.[7]

Solo repertoire

The theorbo's solo Baroque repertoire came almost exclusively from Italy and France, with the exception of some English music written for the English theorbo, until the 21st century. The most effective and idiomatic music for the theorbo takes advantage of its two unique qualities: the diapasons and the reentrant tuning. Campanella passages that allow scale passages to ring across multiple strings in a harp-like fashion are particularly common and are a highly effective tool for the skilled theorbist/composer.[citation needed]

Italy: Kapsberger, Piccinini, Castaldi

- Toccatas - free, rhapsodic, harmonically adventurous. Piccinini's are more harmonically tight while Kapsberger often breaks voice-leading rules in order to achieve the desired effect

- Dances - Gagliardas, continuing in the tradition of Italian lute dances dating back to Dalza

- Variations - highly sophisticated and challenging variations on often very simple themes

France: de Visee, Bartolotti, Hurel, le Moyne

- Dance suites - the vast majority of French theorbo music consists of dance suites in the order of unmeasured prelude, allemande, courante, saraband, gigue (with variations)

- Transcriptions - French theorbists often transcribed pieces from opera composers such as Lully or keyboard composers such as Couperin to perform as solo pieces

A few modern composers have begun to write new music for the theorbo; significant works have been composed by Roman Turovsky, David Loeb, Bruno Helstroffer, Thomas Bocklenberg, and Stephen Goss, who has written the only concerto for theorbo.[citation needed]

Continuo

The theorbo's primary use was as a continuo instrument. However, due to its layout as a plucked instrument and its reentrant tuning, following strict voice leading parameters could sometimes be difficult or even impossible.[citation needed] Thus, a style of continuo unique to the theorbo was developed that incorporated these factors:[citation needed]

- Breaking voice leading rules to capitalize on voicings that better express the instrument's natural sonority. The integrity of the true bass line is maintained through the use of creative arpeggiationthat masks improper inversions.

- Frequent transposition of the bass line down an octave in order to play on the diapasons.

- Use of thinner textures; due to the theorbo's strong projection and rich resonance, a three or even two voice accompaniment will often be just as effective as a standard four-voice accompaniment on a harpsichord. Additionally, playing more than a two-voice realization can become impossible with quick-moving bass lines.

- Frequent restriking of chords to make up for the instrument's quick decay.

Thus, the preservation of the bass line and the sound of the instrument are of the highest priority when used as a continuo instrument. Breaking voice leading rules becomes necessary in order to preserve the bass line and bring out the unique tones of the theorbo.[citation needed]

The theorbo is labelled by Praetorius as both a fundamental and an ornamental continuo instrument, meaning it is capable of supporting an ensemble as a primary bass instrument while also fleshing out the harmony and adding color to the ensemble by means of chord realizations.[8]

Composers

- Giovanni Girolamo Kapsperger (c. 1580–17 January 1651)

- Alessandro Piccinini (30 December 1566–c. 1638)

- Angelo Michele Bartolotti (died before 1682)

- Bellerofonte Castaldi (1580–27 September 1649)

- Robert de Visée (c. 1655–1732/1733)

- Charles Hurel (died 1692)

- Scott Fields (born 1955)

- Stephen Goss (born 2 February 1964)

- Roman Turovsky(born 1961)

Contemporary players

- Xavier Diaz-Latorre (born 1968)

- Eduardo Egüez (born 1959)

- Yasunori Imamura (born 19 October 1953)

- Jakob Lindberg (born 16 October 1952)

- Rolf Lislevand (born 30 December 1961)

- Robert MacKillop(born 1959)

- Massimo Marchese (born 31 August 1965)

- Andreas Martin (born 1963)

- Nigel North (born 5 June 1954)

- Paul O'Dette (born 2 February 1954)

- Christina Pluhar (born 1965)

- Lynda Sayce

- Richard Stone(born 1960)

- Stephen Stubbs (born 1951)

- Matthew Wadsworth (born 1974)

References

- ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Athanasius Kircher, Musurgia Universalis, Rome 1650, p. 476

- ^ OCLC 14377608.

- ^ OCLC 2076633.

- ^ N.Prokopenko "Kobza & Bandura" Kiev, 1977

- ^ Piotr Kowalcze, "Sympozjum: Teorban w polskich zbiorah muzealnych" Warsaw 2008

- ISBN 9780253314154.

- OCLC 68427186.

Sources

- Bacilly, Bénigne de. Remarques Curieuses sur l’Arte de Bien Chanter. Paris, 1688. Translated by Austin B. Caswell as A Commentary upon The Art of Proper Singing. New York: Institute of Medæval Music, 1968.

- Baron, Ernst Gottlieb. Historisch-Theorisch und Practische Untersuchung des Instruments der Lauten. Nurnberg, 1727. Translated by Douglas Alton Smith as Study of the Lute. San Francisco: Instrumenta Antiqua, 1976.

- Burris, Timothy. “Lute and Theorbo in Vocal Music in 18th Century Dresden - A Performance Practice Study.” PhD dissertation, Duke University, 1997.

- Caccini, Giulio. Le nuove musiche. Florence, 1601. Translated by H. Wiley Hitchcock as The New Music. Middleton, Wisconsin: A-R Editions, 2009.

- Cantalupi, Diego. "La tiorba ed il suo uso in Italia come strumento per il basso continuo", pre-press version of the dissertation discussed in 1996 at the Faculty of Musicology, University of Pavia.

- Delair, Denis. Traité d’accompagnement pour le théorbe, et le clavecin. Paris, 1690. Translated by Charlotte Mattax as Accompaniment on Theorbo and Harpsichord. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991.

- Jones, E.H. “The Theorbo and Continuo Practice in the Early English Baroque.” The Galpin Society Journal 25 (July 1972): 67–72.

- Keller, J. Gottfried. A compleat method for attaining to play a thorough bass upon either organ, harpsicord, or theorbo-lute . . . with variety of proper lessons and fuges, explaining the several rules throughout the whole work. London: J. Cullen and J. Young, 1707

- Kitsos, Theodoros. “Continuo Practice for the Theorbo as indicated in Seventeenth-century Italian Printed and Manuscript Sources.” PhD dissertation, University of York, 2005.

- Mason, Kevin Bruce. The Chitarrone and its Repertoire in Early Seventeenth-Century Italy. Aberystwyth, Wales: Boethius Press, 1989.

- Mattax, Charlotte. Translator's Commentary to Accompaniment on Theorbo and Harpsichord, 1-36. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991.

- North, Nigel. Continuo Playing on the Lute, Archlute, and Theorbo. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986.

- Praetorius, Michael. Syntagma Musicum III. Wolfenbüttel, 1619. Translated by Hans Lampl. PhD dissertation, University of Southern California, 1957.

- Rebuffa, Davide. Il liuto, L'Epos, Pelermo 2012

- Schulze-Kurz, Ekkehard. Die Laute und ihre Stimmungen in der ersten Hälfte des 17. Jahrhunderts, 1990, ISBN 3-927445-04-5

- Spencer, Robert. “Chitarrone, Theorbo, and Archlute.” Early Music vol. 4 no. 4 (October 1976): 408-422)

External links

- The virtual home-page of the theorbo

- Chitarrone, theorbo and archlute by Robert Spencer; from Early Music, vol. 4, October 1976

- Theorbo timeline from 1589 to 1818

- Grove Music Online article

- Theorbo article from the Early Music Studio

- Discussion of use of fingernails on the theorbo

- Kenny, Elizabeth. "Introducing the Baroque Theorbo" (Video) – via YouTube.