Third party (U.S. politics)

Third party, or minor party, is a term used in the United States' two-party system for political parties other than the Republican and Democratic parties.

Competitiveness

With few exceptions,

Notable exceptions

Greens, Libertarians, and others have elected state legislators and local officials. The Socialist Party elected hundreds of local officials in 169 cities in 33 states by 1912, including Milwaukee, Wisconsin; New Haven, Connecticut; Reading, Pennsylvania; and Schenectady, New York.[6] There have been governors elected as independents, and from such parties as Progressive, Reform, Farmer-Labor, Populist, and Prohibition. After losing a Republican primary in 2010, Bill Walker of Alaska won a single term in 2014 as an independent by joining forces with the democratic nominee. In 1998, wrestler Jesse Ventura was elected governor of Minnesota on the Reform Party ticket.[7]

Sometimes a national officeholder that is not a member of any party is elected. Previously, Senator Lisa Murkowski won re-election in 2010 as a write-in candidate after losing the Republican primary to a Tea party candidate, and Senator Joe Lieberman ran and won reelection to the Senate as an "Independent Democrat" in 2006 after losing the Democratic primary.[8][9] As of 2023, there are only three U.S. senators, Angus King, Bernie Sanders and Kyrsten Sinema, who identify as Independent and all caucus with the Democrats.[10] Sinema may have left the Democratic Party in 2022 because she thought she could not win a democratic primary race in 2024.[11]

The last time a third-party candidate carried any states in a presidential race was

Barriers to third party success

Winner-take-all vs. proportional representation

In

In the United States, if an interest group is at odds with its traditional party, it has the option of running sympathetic candidates in

Micah Sifry argues that despite years of discontentment with the two major parties in the United States, that third parties should try to arise organically at the local level in places where ranked-choice voting and other more democratic systems makes it easier to build momentum, rather than starting with the presidency which would be incredibly unlikely to succeed.[13]

Spoiler effect

Strategic voting often leads to a third-party that underperforms its poll numbers with voters wanting to make sure their vote helps determine the winner. In response, some third-party candidates express ambivalence about which major party they prefer and their possible role as spoiler[14] or deny the possibility.[15] The US presidential elections most consistently cited as having been spoiled by third-party candidates are 1844, 2000, and 2016.[16][17][18][19][20][21] This phenomenon becomes more controversial when a third-party candidate receives help from supporters of another candidate hoping they play a spoiler role.[22][23][24]

Ballot access laws

Nationally,

Debate rules

Perot did not make the 1996 debates.[27] In 2000, revised debate access rules made it even harder for third-party candidates to gain access by stipulating that, besides being on enough state ballots to win an Electoral College majority, debate participants must clear 15% in pre-debate opinion polls. This rule has continued being in effect as of 2008.[28][29] The 15% criterion, had it been in place, would have prevented Anderson and Perot from participating in the debates in which they appeared. Debates in other state and federal elections often exclude independent and third-party candidates, and the Supreme Court has upheld this practice in several cases. The Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD) is a private company.[30]

Major parties adopt third-party platforms

They can draw attention to issues that may be ignored by the majority parties. If such an issue finds acceptance with the voters, one or more of the major parties may adopt the issue into its own

However, changing positions can be costly for a major party. For example, in the US 2000 Presidential election Magee predicts that Gore shifted his positions to the left to account for Nader, which lost him some valuable centrist voters to Bush.[31] In cases with an extreme minor candidate, not changing positions can help to reframe the more competitive candidate as moderate, helping to attract the most valuable swing voters from their top competitor while losing some voters on the extreme to the less competitive minor candidate.[32]

Current U.S. third parties

Largest

| Party | No. registrations[33] | % registered voters[33] |

|---|---|---|

| Democratic Party | 47,130,651 | 38.73% |

| Republican Party | 36,019,694 | 29.60% |

| Libertarian Party | 732,865 | 0.6% |

Green Party

|

234,120 | 0.19% |

| Constitution Party | 128,914 | 0.11% |

Smaller parties (listed by ideology)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

This section includes only parties that have actually run candidates under their name in recent years.

Right-wing

This section includes any party that advocates positions associated with ideologies.

State-only right-wing parties

- American Independent Party (California)

- Conservative Party of New York State

- Constitution Party of Oregon

Centrist

This section includes any party that is independent, populist, or any other that either rejects left–right politics or does not have a party platform.

- Alliance Party

- American Solidarity Party

- Citizens Party

- Forward Party/Forward

- No Labels

- Reform Party of the United States of America

- Serve America Movement

- United States Pirate Party

- Unity Party of America

State-only centrist parties

- Moderate Party of Rhode Island

- Independent Party of Delaware

- Independent Party of Oregon

- Keystone Party of Pennsylvania

- United Utah Party

- Colorado Center Party

Left-wing

This section includes any party that has a left-liberal, progressive, social democratic, democratic socialist, or Marxist platform.

- Communist Party USA

- Freedom Socialist Party

- Justice Party USA

- People's Party

- Party for Socialism and Liberation

- Peace and Freedom Party

- Socialist Action

- Socialist Equality Party

- Socialist Alternative

- Socialist Party USA

- Socialist Workers Party

- Working Class Party

- Workers World Party

- Working Families Party

State-only left-wing parties

- Charter Party(Cincinnati, Ohio, only)

- Green Mountain Peace and Justice Party (Vermont)

- Green Party of Alaska

- Green Party of Rhode Island

- Labor Party (South Carolina Workers Party)

- Liberal Party of New York

- Oregon Progressive Party

- Progressive Dane (Dane county, Wisconsin)

- United Independent Party (Massachusetts)

- Vermont Progressive Party

- Washington Progressive Party

Ethnic nationalism

This section includes parties that primarily advocate for granting special privileges or consideration to members of a certain race, ethnic group, religion etc.

- American Freedom Party

- Black Riders Liberation Party

- National Socialist Movement

- New Afrikan Black Panther Party

Also included in this category are various parties found in and confined to

Secessionist parties

This section includes parties that primarily advocate for Independence from the United States. (Specific party platforms may range from left wing to right wing).

Single-issue/protest-oriented

This section includes parties that primarily advocate

- Grassroots—Legalize Cannabis Party

- Legal Marijuana Now Party

- Prohibition Party

- United States Marijuana Party[citation needed]

State-only parties

- Approval Voting Party (Colorado)

- Natural Law Party (Michigan)

- New York State Right to Life Party

- Rent Is Too Damn High Party (New York)

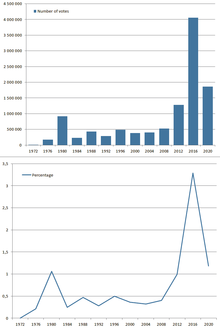

Third-party presidential election results (1992–present)

Only the top 3 third-party candidates by popular vote are listed.

1992

| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ross Perot | Independent | 19,743,821 | 18.91%

|

Maine: 30.44%

|

Andre Verne Marrou

|

Libertarian | 290,087 | 0.28%

|

New Hampshire: 0.66%

|

| Bo Gritz | Populist | 106,152 | 0.10%

|

Utah: 3.84%

|

Other

|

269,507 | 0.24%

|

— | |

Total

|

20,409,567 | 19.53%

|

— | |

1996

| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ross Perot | Reform | 8,085,294 | 8.40%

|

Maine: 14.19%

|

| Ralph Nader | Green | 684,871 | 0.71%

|

Oregon: 3.59%

|

| Harry Browne | Libertarian | 485,759 | 0.50%

|

Arizona: 1.02%

|

Other

|

419,986 | 0.43%

|

— | |

Total

|

9,675,910 | 10.04%

|

— | |

2000

| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ralph Nader | Green | 2,882,955 | 2.74%

|

Alaska: 10.07%

|

| Pat Buchanan | Reform | 448,895 | 0.43%

|

North Dakota: 2.53%

|

| Harry Browne | Libertarian | 384,431 | 0.36%

|

Georgia: 1.40%

|

Other

|

232,920 | 0.22%

|

— | |

Total

|

3,949,201 | 3.75%

|

— | |

2004

| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ralph Nader | Independent | 465,650 | 0.38%

|

Alaska: 1.62%

|

| Michael Badnarik | Libertarian | 397,265 | 0.32%

|

Indiana: 0.73%

|

| Michael Peroutka | Constitution | 143,630 | 0.15%

|

Utah: 0.74%

|

Other

|

215,031 | 0.18%

|

— | |

Total

|

1,221,576 | 1.00%

|

— | |

2008

| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ralph Nader | Independent | 739,034 | 0.56%

|

Maine: 1.45%

|

| Bob Barr | Libertarian | 523,715 | 0.40%

|

Indiana: 1.06%

|

| Chuck Baldwin | Constitution | 199,750 | 0.12%

|

Utah: 1.26%

|

Other

|

404,482 | 0.31%

|

— | |

Total

|

1,866,981 | 1.39%

|

— | |

2012

| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gary Johnson | Libertarian | 1,275,971 | 0.99%

|

New Mexico: 3.60%

|

| Jill Stein | Green | 469,627 | 0.36%

|

|

| Virgil Goode | Constitution | 122,389 | 0.11%

|

Wyoming: 0.58%

|

Other

|

368,124 | 0.28%

|

— | |

Total

|

2,236,111 | 1.74%

|

— | |

2016

| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gary Johnson | Libertarian | 4,489,341 | 3.28%

|

New Mexico: 9.34%

|

| Jill Stein | Green | 1,457,218 | 1.07%

|

Hawaii: 2.97%

|

| Evan McMullin | Independent | 731,991 | 0.54%

|

Utah: 21.54%

|

Other

|

1,149,700 | 0.84%

|

— | |

Total

|

7,828,250 | 5.73%

|

— | |

2020

| Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Best state percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jo Jorgensen | Libertarian | 1,865,535 | 1.18%

|

South Dakota: 2.63%

|

| Howie Hawkins | Green | 407,068 | 0.26%

|

Maine: 1.00%

|

| Rocky De La Fuente | Alliance | 88,241 | 0.0006%

|

California: 0.34%

|

Other

|

561,311 | 0.41%

|

— | |

Total

|

2,922,155 | 1.85%

|

— | |

2024

In 2023 and 2024, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has polled higher than any third-party presidential candidate since Ross Perot[35] in the 1992 and 1996 elections.[36][37][38]

References

- ^ a b O'Neill, Aaron (June 21, 2022). "U.S. presidential elections: third-party performance 1892-2020". Statista. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ Arthur Meier Schlesinger, ed. History of US political parties (5 vol. Chelsea House Pub, 2002).

- ^ Masket, Seth (Fall 2023). "Giving Minor Parties a Chance". Democracy. 70.

- ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- JSTOR 1962968. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ISBN 9781844676798.

- from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ "Senator Lisa Murkowski wins Alaska write-in campaign". Reuters. November 18, 2010. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ Zeller, Shawn. "Crashing the Lieberman Party - New York Times". archive.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ "Justin Amash Becomes the First Libertarian Member of Congress". Reason.com. April 29, 2020. Archived from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ https://www.npr.org/2022/12/09/1141827943/sinema-leaves-democratic-party-independent

- ^ Naylor, Brian (October 7, 2020). "How Maine's Ranked-Choice Voting System Works". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Means, Marianne (February 4, 2001). "Opinion: Goodbye, Ralph". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on May 26, 2002.

- ISBN 978-0-313-36591-1.

- S2CID 237457376.

- doi:10.1561/100.00005039. Pdf.

- S2CID 43919948.

- ^ Roberts, Joel (July 27, 2004). "Nader to crash Dems' party?". CBS News.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie et al (September 22, 2020) "How Republicans Are Trying to Use the Green Party to Their Advantage." New York Times. (Retrieved September 24, 2020.)

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Schreckinger, Ben (June 20, 2017). "Jill Stein Isn't Sorry". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ "Russians launched pro-Jill Stein social media blitz to help Trump, reports say". NBC News. December 22, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ Amato, Theresa (December 4, 2009). "The two party ballot suppresses third party change". The Record. Harvard Law. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

Today, as in 1958, ballot access for minor parties and Independents remains convoluted and discriminatory. Though certain state ballot access statutes are better, and a few Supreme Court decisions (Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968), Anderson v. Celebrezze, 460 U.S. 780 (1983)) have been generally favorable, on the whole, the process—and the cumulative burden it places on these federal candidates—may be best described as antagonistic. The jurisprudence of the Court remains hostile to minor party and Independent candidates, and this antipathy can be seen in at least a half dozen cases decided since Nader's article, including Jenness v. Fortson, 403 U.S. 431 (1971), American Party of Tex. v. White, 415 U.S. 767 (1974), Munro v. Socialist Workers Party, 479 U.S. 189 (1986), Burdick v. Takushi, 504 U.S. 428 (1992), and Arkansas Ed. Television Comm'n v. Forbes, 523 U.S. 666 (1998). Justice Rehnquist, for example, writing for a 6–3 divided Court in Timmons v. Twin Cities Area New Party, 520 U.S. 351 (1997), spells out the Court's bias for the "two-party system," even though the word "party" is nowhere to be found in the Constitution. He wrote that "The Constitution permits the Minnesota Legislature to decide that political stability is best served through a healthy two-party system. And while an interest in securing the perceived benefits of a stable two-party system will not justify unreasonably exclusionary restrictions, States need not remove all the many hurdles third parties face in the American political arena today." 520 U.S. 351, 366–67.

- ^ "What Happened in 1992?", Open Debates, archived from the original on April 15, 2013, retrieved December 20, 2007

- ^ "What Happened in 1996?", Open Debates, archived from the original on April 15, 2013, retrieved December 20, 2007

- ^ "The 15 Percent Barrier", Open Debates, archived from the original on April 15, 2013, retrieved December 20, 2007

- ^ Commission on Presidential Debates Announces Sites, Dates, Formats and Candidate Selection Criteria for 2008 General Election, Commission on Presidential Debates, November 19, 2007, archived from the original on November 19, 2008, retrieved December 20, 2007

- PMID 6157090, archived from the originalon January 1, 2008, retrieved December 20, 2007

- JSTOR 42955889.

- S2CID 54056894.

- ^ a b Winger, Richard (December 27, 2022). "December 2022 Ballot Access News Print Edition". Ballot Access News. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Herbeck, Dan (November 15, 2011). Resentments abound in Seneca power struggle Archived November 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Buffalo News. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ Nuzzi, Olivia (November 22, 2023). "The Mind-Bending Politics of RFK Jr". Intelligencer. Archived from the original on March 6, 2024. Retrieved March 6, 2024.

The general election is now projected to be a three-way race between Biden, Trump, and their mutual, Kennedy, with a cluster of less popular third-party candidates filling out the constellation.

- ^ Benson, Samuel (November 2, 2023). "RFK Jr.'s big gamble". Deseret News. Archived from the original on November 21, 2023. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

Early polls show Kennedy polling in the teens or low 20s

- ^ Enten, Harry (November 11, 2023). "How RFK Jr. could change the outcome of the 2024 election". CNN. Archived from the original on November 20, 2023. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ Collins, Eliza (March 26, 2024). "RFK Jr. to Name Nicole Shanahan as Running Mate for Presidential Bid". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 26, 2024. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

Further reading

- Tamas, Bernard. 2018. The Demise and Rebirth of American Third Parties: Poised for Political Revival? Routledge.

- Epstein, David A. (2012). Left, Right, Out: The History of Third Parties in America. Arts and Letters Imperium Publications. ISBN 978-0-578-10654-0

- Gillespie, J. David. Challengers to Duopoly: Why Third Parties Matter in American Two-Party Politics (University of South Carolina Press, 2012)

- Ness, Immanuel and James Ciment, eds. Encyclopedia of Third Parties in America (4 vol. 2006) (2000 edition)