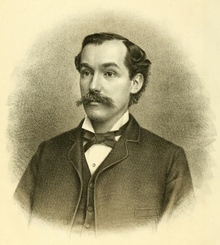

Thomas G. Gentry

Thomas George Gentry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 28, 1843 |

| Died | 1905 |

| Occupation(s) | Ornithologist, writer |

Thomas George Gentry (February 28, 1843 – 1905) was an American educator, ornithologist, naturalist and animal rights writer. Gentry authored an early work applying the term intelligence to plants.

Biography

Gentry was born in Holmesburg area of Philadelphia.[1] In 1861, he entered the profession of teaching in Philadelphia. He was elected principal of Southwest Boys' Grammar School in 1884. He married Mary Shoemaker on December 27, 1864. He received the Sc.D. from Chicago College of Science in 1888.[1]

Gentry resided in

Works

Life-Histories of the Birds of Eastern Pennsylvania

Gentry authored the two-volume Life-Histories of the Birds of Eastern Pennsylvania. The work was based on his personal observations of birds in the

It was positively reviewed in the

In 1912, many years after Gentry's volumes were published, a hostile review in

Nests and Eggs of Birds of the United States

Gentry authored Nests and Eggs of Birds of the United States, in 1882. The book deals exclusively with American oology. It was positively reviewed in The American Naturalist who concluded "we take this opportunity to recommend this elegant work for every library."[9] Conversely, Clinton Hart Merriam negatively reviewed it as a "popular picture book, well adapted for the amusement of children".[10]

The book featured beautiful artwork such as 50 paintings of North American birds, eggs and nests by Edwin Sheppard. It is now a collector's item and worth over $1,350.[11]

Intelligence in Plants and Animals

Gentry authored Life and Immortality: Or, Souls in Plants and Animals, in 1897 which argued for animal and plant consciousness.[12] Several years later it was republished as Intelligence in Plants and Animals by Doubleday.[2][13] Gentry believed that all animals and plants have a soul and will survive death.[14] Historian Ed Folsom described it as "an exhaustive investigation of how such animals as bees, ants, worms and buzzards, as well as all kinds of plants, display intelligence and thus have souls".[2] The book argued that even the "lower animals" will have "a future life, where they will receive a just compensation for the sufferings which so many of them undergo in this world."[2] Gentry believed that the doctrine of immortality for animals would lead to a more humane treatment.[15]

A review in

Selected publications

- On Habits of Some American Species of Birds (1874)

- Life-Histories of the Birds of Eastern Pennsylvania (1876)

- The House Sparrow at Home and Abroad (1878)

- Nests and Eggs of Birds of the United States (1882)

- Family Names from the Irish, Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norman and Scotch Considered in Relation to Their Etymology (1892)

- Pigeon River and Other Poems (1892)

- Life and Immortality: Or, Souls in Plants and Animals (1897)

- Intelligence in Plants and Animals (1900)

References

- ^ a b The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans, Volume 4. Boston: The Biographical Society, 1904.

- ^ .

- ^ Quarterly Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club. 1: 49–50.

- ^ The American Journal of Science and Arts. 114: 426. 1877.

- Canadian Entomologist. 9: 37–38. 1877.

- ^ "Life Histories of the Birds of Eastern Pennsylvania". Field and Forest. 2 (6): 106. 1876.

- Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club. 3 (1): 36–37.

- ^ The Auk. 29 (1): 119–121. 1912.

- JSTOR 2449244.

- Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club. 7 (4): 246–249.

- ISBN 978-0-292-71451-9

- ^ The Journal of Practical Metaphysics. 2: 64. 1897.

- ^ "Intelligence in Plants and Animals". The Churchman. 82 (5): 5. 1900.

- ^ "Intelligence in Plants and Animals". Current Literature. 28: 351. 1900.

- The American Journal of Psychology. 9: 133. 1897.

- ^ "Intelligence in Plants and Animals". The Nation. 72 (1869): 344. 1901.