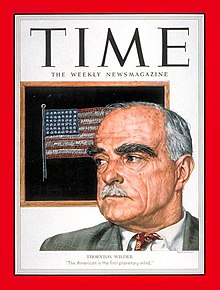

Thornton Wilder

Thornton Wilder | |

|---|---|

Pulitzer Prize for the Novel (1927) | |

| Relatives | Thornton M. Niven |

Thornton Niven Wilder (April 17, 1897 – December 7, 1975) was an American playwright and novelist. He won three Pulitzer Prizes for the novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey and for the plays Our Town and The Skin of Our Teeth, and a U.S. National Book Award for the novel The Eighth Day.

Early life and education

Wilder was born in Madison, Wisconsin, the son of Amos Parker Wilder, a newspaper editor[1] and later a U.S. diplomat, and Isabella Thornton Niven.[2]

Wilder had four siblings as well as a twin who was stillborn.[3] All of the surviving Wilder children spent part of their childhood in China when their father was stationed in Hong Kong and Shanghai as U.S. Consul General. Thornton's older brother, Amos Niven Wilder, became Hollis Professor of Divinity at the Harvard Divinity School. He was a noted poet and was instrumental in developing the field of theopoetics. Their sister Isabel Wilder was an accomplished writer. They had two more sisters, Charlotte Wilder, a poet, and Janet Wilder Dakin, a zoologist.[4]

Education

Wilder began writing plays while at the

Wilder served a three-month enlistment in the

Career

After graduating, Wilder went to Italy and studied

Proficient in four languages,[8] Wilder translated plays by André Obey and Jean-Paul Sartre. He wrote the libretti of two operas, The Long Christmas Dinner, composed by Paul Hindemith, and The Alcestiad, composed by Louise Talma and based on his own play. Alfred Hitchcock, whom he admired, asked him to write the screenplay of his thriller Shadow of a Doubt,[15] and he completed a first draft for the film.[8]

The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927) tells the story of several unrelated people who happen to be on a bridge in

Wilder wrote

In 1938, Max Reinhardt directed a Broadway production of The Merchant of Yonkers, which Wilder had adapted from Austrian playwright Johann Nestroy's Einen Jux will er sich machen (1842). It was a failure, closing after 39 performances.[21]

His play The Skin of Our Teeth opened in New York on November 18, 1942, featuring Fredric March and Tallulah Bankhead. Again, the themes are familiar – the timeless human condition; history as progressive, cyclical, or entropic; literature, philosophy, and religion as the touchstones of civilization. Three acts dramatize the travails of the Antrobus family, allegorizing the alternate history of mankind. It was claimed by Joseph Campbell and Henry Morton Robinson, authors of A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, that much of the play was the result of unacknowledged borrowing from James Joyce's last work.[fn 2][22]

In his novel

In 1954,

In 1960, Wilder was awarded the first ever

In 1962 and 1963, Wilder lived for 20 months in the small town of Douglas, Arizona, apart from family and friends. There he started his longest novel, The Eighth Day, which went on to win the National Book Award.[14] According to Harold Augenbraum in 2009, it "attack[ed] the big questions head on, ... [embedded] in the story of small-town America".[26]

His last novel, Theophilus North, was published in 1973, and made into the film Mr. North in 1988.[27]

The Library of America republished all of Wilder's plays in 2007, together with some of his writings on the theater and the screenplay of Shadow of a Doubt.[28] In 2009, a second volume was released, containing his first five novels, six early stories, and four essays on fiction.[29] Finally, the third and final volume in the Library of America series on Wilder was released in 2011, containing his last two novels The Eighth Day and Theophilus North, as well as four autobiographical sketches.[30]

Personal life

Six years after Wilder’s death, Samuel Steward wrote in his autobiography that he had sexual relations with him.[31] In 1937, Gertrude Stein had given Steward, then a college professor, a letter of introduction to Wilder. According to Steward, Alice B. Toklas told him that Wilder liked him and that Wilder had reported he was having trouble starting the third act of Our Town until he and Steward walked around Zürich all night in the rain and the next day wrote the whole act, opening with a crowd in a rainy cemetery.[32] Penelope Niven disputes Steward's claim of a relationship with Wilder and, based on Wilder's correspondence, says Wilder worked on the third act of Our Town over the course of several months and completed it several months before he first met Steward.[33] Robert Gottlieb, reviewing Penelope Niven's work in The New Yorker in 2013, claimed Wilder had become infatuated with a man, not identified by Gottlieb, and Wilder’s feelings were not reciprocated. Gottlieb asserted that "Niven ties herself in knots in her discussion of Wilder’s confusing sexuality" and that "His interest in women was unshakably nonsexual." He takes Steward's view that Wilder was a latent homosexual but never comfortable with sex.[34]

Wilder had a wide circle of friends, including writers

From the earnings of The Bridge of San Luis Rey, in 1930 Wilder had a house built for his family in Hamden, Connecticut, designed by Alice Trythall Washburn, one of few female architects working at the time. His sister Isabel lived there for the rest of her life. This became his home base, although he traveled extensively and lived away for significant periods.

Death

Wilder died of heart failure in his Hamden, Connecticut house on December 7, 1975,[8] at age 78. He is interred at Mount Carmel Cemetery in Hamden.[35]

Bibliography

Plays

- The Trumpet Shall Sound (1926)

- The Angel That Troubled the Waters and Other Plays (1928):[36]

- "Nascuntur Poetae"

- "Proserpina and the Devil"

- "Fanny Otcott"

- "Brother Fire"

- "The Penny That Beauty Spent"

- "The Angel on the Ship"

- "The Message and Jehanne"

- "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came"

- "Centaurs"

- "Leviathan"

- "And the Sea Shall Give Up Its Dead"

- "The Servant's Name Was Malchus"

- "Mozart and the Gray Steward"

- "Hast Thou Considered My Servant Job?"

- "The Flight Into Egypt"

- "The Angel That Troubled the Waters"

- The Long Christmas Dinner and Other Plays in One Act (1931):

- The Long Christmas Dinner

- Queens of France

- Pullman Car Hiawatha

- Love and How to Cure It

- Such Things Only Happen in Books

- The Happy Journey to Trenton and Camden

- Our Town (1938)—won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama[20]

- The Merchant of Yonkers (1938)

- The Skin of Our Teeth (1942)—won the Pulitzer Prize[20]

- The Matchmaker (1954)—revised from The Merchant of Yonkers

- The Alcestiad: Or, a Life in the Sun (1955)

- Childhood (1960)

- Infancy (1960)

- Plays for Bleecker Street (1962)

- The Collected Short Plays of Thornton Wilder Volume I (1997):

- The Long Christmas Dinner

- Queens of France

- Pullman Car Hiawatha

- Love and How to Cure It

- Such Things Only Happen in Books

- The Happy Journey to Trenton and Camden

- The Drunken Sisters

- Bernice

- The Wreck on the Five-Twenty-Five

- A Ringing of Doorbells

- In Shakespeare and the Bible

- Someone from Assisi

- Cement Hands

- Infancy

- Childhood

- Youth

- The Rivers Under the Earth

- Our Town

Films

- Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

Novels

- The Cabala (1926)

- Pulitzer Prize for the Novel[9]

- The Woman of Andros (1930)—based on Andria, a comedy by Terence

- Heaven's My Destination (1935)

- Ides of March(1948)

- The Eighth Day (1967)—won the National Book Award for Fiction[14]

- Theophilus North (1973)—reprinted as Mr. North following the appearance of the film of the same name

Collections

- Wilder, Thornton (2007). McClatchy, J. D. (ed.). Thornton Wilder, Collected Plays and Writings on Theater. ISBN 978-1-59853-003-2.

- Wilder, Thornton (2009). McClatchy, J. D. (ed.). Thornton Wilder, The Bridge of San Luis Rey and Other Novels 1926–1948. Library of America. Vol. 194. New York: Library of America. ISBN 978-1-59853-045-2.

- Wilder, Thornton (2011). McClatchy, J. D. (ed.). Thornton Wilder, The Eighth Day, Theophilus North, Autobiographical Writings. Library of America. Vol. 222. New York: Library of America. ISBN 978-1-59853-146-6.

Further reading

- Gallagher-Ross, Jacob. 2018. "Theaters of the Everyday". Evanston: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-3666-3.

- Gottlieb, Robert (January 7, 2013). "Man of Letters: The Case of Thornton Wilder". The New Yorker. Vol. 88, no. 42. pp. 71–76. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- Kennedy, Harold J. 1978. "No Pickle, No Performance. An Irreverent Theatrical Excursion from Tallulah to Travolta". Doubleday & Co.

Notes

- Member of the Order of the British Empire(MBE) from Britain.

- ISBN 978-1-57731-406-6reprints the reviews and discusses the controversy.

References

- ^ a b c Isherwood, Charles (October 31, 2012). "A Life Captured With Luster Left Intact". The New York Times. p. C1. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ^ Man of Letters: The Case of Thornton Wilder By Robert Gottlieb, December 31, 2012 Published in print in the column A Critic at Large in the January 7, 2013, issue of The New Yorker. Accessed online May 4, 2020.

- ^ Niven, Penelope (2012). Thornton Wilder: A Life. Harper. pp. 92, 370.

- The Berkeley Daily Planet.

- ^ "Biography". Thornton Wilder. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Chronology". Thornton Wilder Society. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-06-051263-7.

- ^ a b ""Novel": Past winners & finalists by category". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ Siegel, Barbara; Siegel, Scott (May 22, 2000). "Lucrece". TheaterMania.com.

- ^ Jones, Chris. "Our town was Wilder's town too". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ "Drama – The Pulitzer Prizes". Pulitzer. Columbia University. 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ^ [1] The Wilder Family Website

- ^ a b c "National Book Awards – 1968". National Book Foundation. Retrieved March 28, 2012. (With an essay by Harold Augenbraum from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.)

- .

- ^ "Text of Tony Blair's reading in New York". The Guardian. London, UK. September 21, 2001. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-5275-2364-7.

- ^ Erhard, Elise. "Searching for Our Town". Crisis Magazine. February 7, 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-8262-6497-8

- ^ a b c "Drama". Past winners & finalists by category. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ Niven, Penelope (2012). Thornton Wilder: A Life. Harper. p. 471.

- ISBN 978-1-57731-471-4.

- ISBN 978-0-80320-057-9.

- ^ "Hello Dolly! – New Wimbledon Theatre (Review)". indielondon.co.uk. March 2008.

- ^ "Macdowell Medalists". Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ Augenbraum, Harold (July 23, 2009). "1968: The Eighth Day by Thornton Wilder". National Book Foundation. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ Longsdorf, Amy (November 17, 1988). "With 'Mr. North,' Danny Huston Gets His Bearings As A Director". The Morning Call.

- ISBN 978-1-59853-003-2.

- ISBN 978-1-59853-045-2.

- ISBN 978-1-59853-146-6.

- ^ Mulderig, Jeremy, ed. (2018). The Lost Autobiography of Samuel Steward: Recollections of an Extraordinary Twentieth-Century Gay Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 118–124.

- ISBN 0-395-25340-3.

- ISBN 978-0-06083-136-3.

- ^ Gottlieb, Robert (January 7, 2013). "Man of Letters". The New Yorker. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons (3rd ed.). McFarland & Company, Inc. (Kindle Location 50886).

- ^ "Thornton Wilder: Collected Plays and Writings on Theater". Library of America. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

External links

- Official website

- Works by Thornton Wilder in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Thornton Wilder at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thornton Wilder at Internet Archive

- Works by Thornton Wilder at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Thornton Wilder Society

- Richard H. Goldstone (Winter 1956). "Thornton Wilder, The Art of Fiction No. 16". The Paris Review. Winter 1956 (15).

- "Thornton Wilder". Find a Grave. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- Thornton Wilder at the Internet Broadway Database Retrieved on May 18, 2009

- Thornton Wilder at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Thornton Wilder Collection at the Harry Ransom Center

- Biography from The Thornton Wilder Society

- Today in History, The Library of Congress, April 17

- Thornton Wilder Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- Thornton Wilder Collection. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- Finding aid to Thornton Wilder letters at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Guide to the Thornton Wilder Papers 1939–1968 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center