Tibetan Empire

This article's lead section may be too long. (June 2023) |

Tibetan Empire བོད་ཆེན་པོ bod chen po | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 618–842/848 | |||||||||||||||

|

Standard of the Tibetan king Government Monarchy | | ||||||||||||||

| Tsenpo (Chief) | |||||||||||||||

• 618–650 | Songtsen Gampo (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 753–797 | Trisong Detsen | ||||||||||||||

• 815–838 | Ralpachen | ||||||||||||||

• 841–842[2] | U Dum Tsen (last) | ||||||||||||||

Gar Tongtsen Yülsung | |||||||||||||||

• 685–699 | Gar Trinring Tsendro | ||||||||||||||

• 782?–783 | Nganlam Takdra Lukhong | ||||||||||||||

• 783–796 | Nanam Shang Gyaltsen Lhanang | ||||||||||||||

| Banchenpo (Chief Monk) | |||||||||||||||

• 798–? | Nyang Tingngezin Sangpo (first) | ||||||||||||||

• ?–838 | Dranga Palkye Yongten (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 618 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 842/848 | ||||||||||||||

Population | |||||||||||||||

• 7th–8th century[5] | 10 million | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| History of Tibet |

|---|

|

| See also |

|

|

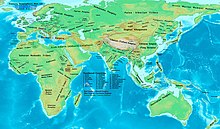

The Tibetan Empire (Tibetan: བོད་ཆེན་པོ, Wylie: bod chen po, lit. 'Great Tibet'; Chinese: 吐蕃; pinyin: Tǔbō / Tǔfān) was an empire centered on the Tibetan Plateau, formed as a result of imperial expansion under the Yarlung dynasty heralded by its 33rd king, Songtsen Gampo, in the 7th century. The empire further expanded under the 38th king, Trisong Detsen, and expanded to its greatest extent under the 41st king, Rapalchen, whose 821–823 treaty was concluded between the Tibetan Empire and the Tang dynasty. This treaty, carved into the Jokhang Pillar, delineated Tibet as being in possession of an area larger than the Tibetan Plateau, stretching east to Chang'an, west beyond modern Afghanistan, and south into modern India and the Bay of Bengal.[6]

The Yarlung dynasty was founded in 127 BCE in the

Before the empire period, sacred Buddhist relics were discovered by the Yarlung dynasty's 28th king, Iha-tho-tho-ri (Thori Nyatsen), and then safeguarded.

The empire period then corresponded to the reigns of Tibet's three 'Religious Kings',[7] which includes King Rapalchen's reign. After Rapalchen's murder, King Lang darma nearly destroyed Tibetan Buddhism[7] through his widespread targeting of Nyingma monasteries and monastic practitioners. His undertakings correspond to the subsequent dissolution of the unified empire period, after which semi-autonomous polities of chieftains, minor kings and queens, and those surviving Tibetan Buddhist polities evolved once again into autonomous independent polities, similar to those polities also documented in the Tibetan Empire's nearer frontier region of Do Kham (Amdo and Kham).[10][11]

Other unreferenced ideas about the dissolution of the empire period include: The varied terrain of the empire and the difficulty of transportation, coupled with the new ideas that came into the empire as a result of its expansion, helped to create stresses and power blocs that were often in competition with the ruler at the center of the empire.[

History

Namri Songtsen and founding of the dynasty

The power that became the Tibetan state originated at the

- "This first mention of the name Bod, the usual name for Tibet in the later Tibetan historical sources, is significant in that it is used to refer to a conquered region. In other words, the ancient name Bod originally referred only to a part of the Tibetan Plateau, a part which, together with Rtsaṅ (Tsang, in Tibetan now spelled Gtsaṅ) has come to be called Dbus-gtsaṅ (Central Tibet)."[13]

Reign of Songtsen Gampo (618–650)

Songtsen Gampo (Srong-brtsan Sgam-po) (c. 604 – 650) was the first great emperor who expanded Tibet's power beyond Lhasa and the Yarlung Valley, and is traditionally credited with introducing Buddhism to Tibet.

When his father Namri Songtsen died by poisoning (circa 618 (mgar-stong-btsan).

The Chinese records mention an envoy to Tibet in 634. On that occasion, the Tibetan Emperor requested (demanded according to Tibetan sources) marriage to a Chinese princess but was refused. In 635-36 the Emperor attacked and defeated the

Circa 639, after Songtsen Gampo had a dispute with his younger brother Tsänsong (Brtsan-srong), the younger brother was burned to death by his own minister Khäsreg (Mkha’s sregs) (presumably at the behest of his older brother the emperor).[17][18]

The Chinese Princess Wencheng (Tibetan: Mung-chang Kung-co) departed China in 640 to marry Songtsen Gampo's son. She arrived a year later. This is traditionally credited with being the first time that Buddhism came to Tibet, but it is very unlikely Buddhism extended beyond foreigners at the court.

Songtsen Gampo’s sister Sämakar (Sad-mar-kar) was sent to marry Lig-myi-rhya, the king of Zhangzhung in what is now Western Tibet. However, when the king refused to consummate the marriage, she then helped her brother to defeat Lig myi-rhya and incorporate Zhangzhung into the Tibetan Empire. In 645, Songtsen Gampo overran the kingdom of Zhangzhung.

Songtsen Gampo died in 650. He was succeeded by his infant grandson

After the death of Songtsen Gampo in 650 AD, the Chinese Tang dynasty attacked and took control of the Tibetan capital Lhasa.[25][26] Soldiers of the Tang dynasty could not sustain their presence in the hostile environment of the Tibetan Plateau and soon returned to China proper."[27]

Reign of Mangsong Mangtsen (650–676)

After having incorporated Tuyuhun into Tibetan territory, the powerful minister Gar Tongtsen died in 667.

Between 665 and 670,

Emperor

Reign of Tridu Songtsen (677–704)

The power of Emperor

In 685, minister Gar Tsenye Dompu (mgar btsan-snya-ldom-bu) died and his brother, Gar Tridring Tsendrö (mgar Khri-‘bring-btsan brod) was appointed to replace him.[31] In 692, the Tibetans lost the Tarim Basin to the Chinese. Gar Tridring Tsendrö defeated the Chinese in battle in 696 and sued for peace. Two years later in 698 emperor Tridu Songtsen reportedly invited the Gar clan (who numbered more than 2000 people) to a hunting party and had them massacred. Gar Tridring Tsendrö then committed suicide, and his troops joined the Chinese. This brought to an end the influence of the Gar.[32]

From 700 until his death the emperor remained on campaign in the northeast, absent from Central Tibet, while his mother Thrimalö administrated in his name.

During the summer of 703, Tridu Songtsen resided at Öljak (‘Ol-byag) in Ling (Gling), which was on the upper reaches of the Yangtze, before proceeding with an invasion of Jang (‘Jang), which may have been either the Mosuo or the kingdom of Nanzhao.[34] In 704, he stayed briefly at Yoti Chuzang (Yo-ti Chu-bzangs) in Madrom (Rma-sgrom) on the Yellow River. He then invaded Mywa, which was at least in part Nanzhao (the Tibetan term mywa likely referring to the same people or peoples referred to by the Chinese as Man or Miao)[35][36][37] but died during the prosecution of that campaign.[33]

Reign of Tride Tsuktsän (704–754)

Gyeltsugru (Rgyal-gtsug-ru), later to become King Tride Tsuktsen (Khri-lde-gtsug-brtsan), generally known now by his nickname

Thrimalö had arranged for a royal marriage to a Chinese princess. The Princess Jincheng (Tibetan: Kyimshang Kongjo) arrived in 710, but it is somewhat unclear whether she married the seven-year-old Gyeltsugru[39] or the deposed Lha Balpo.[40] Gyeltsugru also married a lady from Jang (Nanzhao) and another born in Nanam.[41]

Gyältsugru was officially enthroned with the royal name Tride Tsuktsän in 712,[33] the year that dowager empress Thrimalö died.

The

The Tibetans aided the Turgesh in fighting against the Muslim Arabs during the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana.[42]

In 734, the Tibetans married their princess Dronmalön (‘Dron ma lon) to the Türgesh Qaghan. The Chinese allied with the Caliphate to attack the Türgesh. After victory and peace with the Türgesh, the Chinese attacked the Tibetan army. The Tibetans suffered several defeats in the east, despite strength in the west. The Türgesh empire collapsed from internal strife. In 737, the Tibetans launched an attack against the king of Bru-za (Gilgit), who asked for Chinese help, but was ultimately forced to pay homage to Tibet. In 747, the hold of Tibet was loosened by the campaign of general Gao Xianzhi, who tried to re-open the direct communications between Central Asia and Kashmir.

By 750, the Tibetans had lost almost all of their central Asian possessions to the Chinese. In 753, even the kingdom of "Little Balur" (modern Gilgit) was captured by the Chinese. However, after Gao Xianzhi's defeat by the Caliphate and Karluks at the Battle of Talas (751), Chinese influence decreased rapidly and Tibetan influence began to increase again. Tibet conquered large sections of northern India during this time.

In 755, Tride Tsuktsen was killed by the ministers Lang and ‘Bal. Then Takdra Lukong (Stag-sgra Klu-khong) presented evidence to prince Song Detsen (Srong-lde-brtsan) that they were disloyal and causing dissension in the country, and were about to attack him also. Lang and ‘Bal subsequently did revolt; they were killed by the army and their property was confiscated.[43]

Reign of Trisong Detsen (756–797?)

In 756, prince Song Detsän was crowned Emperor with the name Trisong Detsen (Khri srong lde brtsan) and took control of the government when he attained his majority[44] at 13 years of age (12 by Western reckoning) after a one-year interregnum during which there was no emperor.

In 755, China had already begun to be weakened because of the

In 785, Wei Kao, a Chinese serving as an official in Shuh, repulsed Tibetan invasions of the area.[47]

In the meantime, the

Recent historical research indicates the presence of

There is a stone pillar (now blocked off from the public), the Lhasa Shöl rdo-rings, Doring Chima or

Reign of Muné Tsenpo (c. 797–799?)

Trisong Detsen is said to have had four sons. The eldest, Mutri Tsenpo, apparently died young. When Trisong Detsen retired he handed power to the eldest surviving son, Muné Tsenpo (Mu-ne btsan-po).[53] Most sources say that Muné's reign lasted only about a year and a half. After a short reign, Muné Tsenpo was supposedly poisoned on the orders of his mother.

After his death, Mutik Tsenpo was next in line to the throne. However, he had been apparently banished to Lhodak Kharchu (lHo-brag or Lhodrag) near the Bhutanese border for murdering a senior minister.[54] The youngest brother, Tride Songtsen, was definitely ruling by AD 804.[55][56]

Reign of Tride Songtsen (799–815)

Under Tride Songtsen (Khri lde srong brtsan – generally known as

Reign of Tritsu Detsen (815–838)

Tritsu Detsen (Khri gtsug lde brtsan), best known as

Tibetans attacked Uyghur territory in 816 and were in turn attacked in 821. After successful Tibetan raids into Chinese territory, Buddhists in both countries sought mediation.[58]

Ralpacan was apparently murdered by two pro-

Tibet continued to be a major Central Asian empire until the mid-9th century. It was under the reign of Ralpacan that the political power of Tibet was at its greatest extent, stretching as far as Mongolia and Bengal, and entering into treaties with China on a mutual basis.

A Sino-Tibetan treaty was agreed on in 821/822 under Ralpacan, which established peace for more than two decades.

Reign of Langdarma (838–842)

The reign of Langdarma (Glang dar ma), regal title Tri Uidumtsaen (Khri 'U'i dum brtsan), was plagued by external troubles. The Uyghur state to the north collapsed under pressure from the Kyrgyz in 840, and many displaced people fled to Tibet. Langdarma himself was assassinated, apparently by a Buddhist hermit, in 842.[62][63]

Decline

A civil war that arose over Langdarma's successor led to the collapse of the Tibetan Empire. The period that followed, known traditionally as the Era of Fragmentation, was dominated by rebellions against the remnants of imperial Tibet and the rise of regional warlords.[64]

Military

Armor

The soldiers of the Tibetan Empire wore armour such as lamellar and chainmail, and were proficient in the use of swords and lances. According to the Tibetan author Tashi Namgyal, writing in 1524, the history of lamellar armour in Tibet was divided into three distinct periods. The oldest armour dated from the time of the "Righteous Kings, Uncle, and Nephew" which would place it sometime during the Yarlung dynasty, early seventh to mid ninth century. [65]

According to Du You (735–812) in his encyclopaedic text, the Tongdian, the Tibetans were less proficient in archery and fought in the following manner:

The men and horses all wear chain mail armor. Its workmanship is extremely fine. It envelops them completely, leaving openings only for the two eyes. Thus, strong bows and sharp swords cannot injure them. When they do battle, they must dismount and array themselves in ranks. When one dies, another takes his place. To the end, they are not willing to retreat. Their lances are longer and thinner than those in China. Their archery is weak but their armor is strong. The men always use swords; when they are not at war they still go about carrying swords.[66]

— Du You

The Tibetans might have exported their armour to the neighbouring steppe nomads. When the

Organization

The Tibetan Empire's officers were not employed full-time and were only called upon on an ad hoc basis. These warriors were designated by a golden arrow seven inches long which signified their office. The officers gathered once a year to swear an oath of fealty. They assembled every three years to partake in a sacrificial feast.[68]

While on campaign, Tibetan armies carried no provision of grain and lived on plunder.[69]

Society

The early Tibetans worshipped a god of war known as "Yuandi" (Chinese transcription) according to a Chinese transliteration from the Old Book of Tang.[70]

The Old Book of Tang states:

They grow no rice but have black oats, red pulse, barley, and buckwheat. The principal domestic animals are the yak, pig, dog, sheep, and horse. There are flying squirrels, sembling in shape those of our own country, but as large as cats, the fur of which is used for clothes. They have abundance of gold, silver, copper, and tin. The natives generally follow their flocks to pasture and have no fixed dwelling-place. They have, however, some walled cities. The capital of the state is called the city of Lohsieh. The houses are all flat-roofed and often reach to the height of several tens of feet. The men of rank live in large felt tents, which are called fulu. The rooms in which they live are filthily dirty, and they never comb their hair nor wash. They join their hands to hold wine, and make plates of felt, and knead dough into cups, which they fill with broth and cream and eat the whole together.[69]

See also

References

Citations

- ISBN 978-0-631-22574-4. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2021 – via Reed.edu.

- ^ Arthur Mandelbaum, "Lhalung Pelgyi Dorje", Treasury of Lives

- from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ Chen, Zhitong; Liu, Jianbao; Rühland, Kathleen M.; Zhang, Jifeng; Zhang, Ke; Kang, Wengang; Chen, Shengqian; Wang, Rong; Zhang, Haidong; Smol, John P. (2023-10-01). "Collapse of the Tibetan Empire attributed to climatic shifts: Paleolimnological evidence from the western Tibetan Plateau". Quaternary Science Reviews. 317: 108280. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108280. ISSN 0277-3791.

- ^ Claude Arpi, "Glimpse on the History of Tibet". Dharamsala: The Tibet Museum, p.5.

- ^ a b c d e Claude Arpi."Glimpses on The History of Tibet". The Tibet Museum, 2013

- ^ H.E.Richardson, "The Sino-Tibetan Treaty Inscription of AD 821–823 at Lhasa", JRAS, 2, 1978.

- ^ a b c Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche, "The Eight Manifestations of Guru Padmasambhava". Translated by Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche, edited by Padma Shugchang. Turtle Hill: 1992.

- ^ Jann Ronis, "An overview of Kham (Eastern Tibet) historical polities", University of Virginia, SHANTI Places, 2011.

- ^ Gray Tuttle, "An overview of Amdo (Eastern Tibet) historical polities", University of Virginia, SHANTI Places, 2013.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pg. 17.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 16.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 19–20

- Old Tibetan Annals, hereafter OTA l. 2

- ^ OTA l. 4–5

- ^ a b Richardson, Hugh E. (1965). "How Old was Srong Brtsan Sgampo", Bulletin of Tibetology 2.1. pp. 5–8.

- ^ a b OTA l. 8–10

- ^ OTA l. 607

- ^ Powers 2004, pp. 168–69

- ^ Karmey, Samten G. (1975). "'A General Introduction to the History and Doctrines of Bon", p. 180. Memoirs of Research Department of The Toyo Bunko, No, 33. Tokyo.

- ^ Powers 2004, pg. 168

- ^ Lee 1981, pp. 7–9

- ^ Pelliot 1961, pp. 3–4

- ISBN 978-81-208-1048-8. Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ University of London. Contemporary China Institute, Congress for Cultural Freedom (1960). The China quarterly, Issue 1. p. 88. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-0331-8. Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ISBN 0-691-02469-3.

- ^ Beckwith, 36, 146.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 14, 48, 50.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pg. 50

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 14, 48, 50

- ^ a b c d e Petech, Luciano (1988). "The Succession to the Tibetan Throne in 704-5." Orientalia Iosephi Tucci Memoriae Dicata, Serie Orientale Roma 41.3. pp. 1080–87.

- ISBN 978-0-521-22733-9.

- ^ Backus (1981) pp. 43–44

- ^ Beckwith, C. I. "The Revolt of 755 in Tibet", p. 5 note 10. In: Weiner Studien zur Tibetologie und Buddhismuskunde. Nos. 10–11. [Ernst Steinkellner and Helmut Tauscher, eds. Proceedings of the Csoma de Kőrös Symposium Held at Velm-Vienna, Austria, 13–19 September 1981. Vols. 1–2.] Vienna, 1983.

- ^ Beckwith (1987) pp. 64–65

- ^ Beckwith, C. I. "The Revolt of 755 in Tibet", pp. 1–14. In: Weiner Studien zur Tibetologie und Buddhismuskunde. Nos. 10–11. [Ernst Steinkellner and Helmut Tauscher, eds. Proceedings of the Csoma de Kőrös Symposium Held at Velm-Vienna, Austria, 13–19 September 1981. Vols. 1–2.] Vienna, 1983.

- ^ Yamaguchi 1996: 232

- ^ Beckwith 1983: 276.

- ^ Stein 1972, pp. 62–63

- ISBN 978-0-691-02469-1. Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Beckwith 1983: 273

- ^ Stein 1972, p. 66

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pg. 146

- ^ Marks, Thomas A. (1978). "Nanchao and Tibet in South-western China and Central Asia." The Tibet Journal. Vol. 3, No. 4. Winter 1978, pp. 13–16.

- ^ William Frederick Mayers (1874). The Chinese reader's manual: A handbook of biographical, historical, mythological, and general literary reference. American Presbyterian mission press. p. 249. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 144–157

- ^ Palmer, Martin, The Jesus Sutras, Mackays Limited, Chatham, Kent, Great Britain, 2001)

- ^ Hunter, Erica, "The Church of the East in Central Asia," Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, 78, no.3 (1996)

- ^ Stein 1972, p. 65

- ISBN 0-947593-00-4.

- ISBN 0-8047-0901-7(pbk)

- ^ Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. Tibet: A Political History (1967), p. 47. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

- ^ Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. Tibet: A Political History (1967), p. 48. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

- ISBN 0-947593-00-4.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 157–165

- ^ a b Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. (1967). Tibet: A Political History, pp. 49–50. Yale University Press, New Haven & London.

- ISBN 0-89800-146-3.

- ^ Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. (1967). Tibet: A Political History, p. 51. Yale University Press, New Haven & London.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 165–67

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 168–69

- ^ Shakabpa, p. 54.

- ^ Schaik, Galambos. p.4.

- ^ LaRocca 2006, p. 52.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 110.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 109.

- ^ Bushell 1880, p. 410-411.

- ^ a b Bushell 1880, p. 442.

- ^ Walter 2009, p. 26.

Sources

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (1987), The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-02469-3

- Bushell, S. W. (1880), The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources, Cambridge University Press

- LaRocca, Donald J. (2006), Warriors of the Himalayas: Rediscovering the Arms and Armor of Tibet, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0-300-11153-3

- Lee, Don Y. The History of Early Relations between China and Tibet: From Chiu t'ang-shu, a documentary survey (1981) Eastern Press, Bloomington, Indiana. ISBN 0-939758-00-8

- Pelliot, Paul. Histoire ancienne du Tibet (1961) Librairie d'Amérique et d'orient, Paris

- Powers, John. History as Propaganda: Tibetan Exiles versus the People's Republic of China (2004) Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517426-7

- ISBN 978-3-11-022565-5

- Stein, Rolf Alfred. Tibetan Civilization (1972) Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0901-7

- Walter, Michael L. (2009), Buddhism and Empire The Political and Religious Culture of Early Tibet, Brill

- Yamaguchi, Zuiho. (1996). “The Fiction of King Dar-ma’s persecution of Buddhism” De Dunhuang au Japon: Etudes chinoises et bouddhiques offertes à Michel Soymié. Genève : Librarie Droz S.A.

- Nie, Hongyin. 西夏文献中的吐蕃[permanent dead link]

Further reading

- "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources" S. W. Bushell, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, New Series, Vol. 12, No. 4 (Oct. 1880), pp. 435–541, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland

External links

Media related to Tibetan Empire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tibetan Empire at Wikimedia Commons

![[citation needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/Tibetan_snow_leopard.svg/125px-Tibetan_snow_leopard.svg.png)