Tiger

| Tiger Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A Bengal tigress in Kanha Tiger Reserve, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. tigris

|

| Binomial name | |

| Panthera tigris | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Tiger distribution as of 2022 | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

The tiger (Panthera tigris) is the largest living

Throughout the tiger's range, it inhabits mainly forests, from

Since the early 20th century, tiger populations have lost at least 93% of their historic range and are

The tiger is among the most popular of the world's

Etymology

The

Taxonomy

In 1758,

Subspecies

Following Linnaeus's first descriptions of the species, several tiger zoological specimens were described and proposed as subspecies.[9] The validity of several tiger subspecies was questioned in 1999. Most putative subspecies described in the 19th and 20th centuries were distinguished on the basis of fur length and colouration, striping patterns and body size, hence characteristics that vary widely within populations. Morphologically, tigers from different regions vary little, and gene flow between populations in those regions is considered to have been possible during the Pleistocene. Therefore, it was proposed to recognise only two tiger subspecies as valid, namely P. t. tigris in mainland Asia and P. t. sondaica in the Greater Sunda Islands. Mainland tigers are described as being larger in size with generally lighter fur and fewer stripes, while island tigers are smaller due to insular dwarfism, with darker coats and more numerous stripes.[10] The stripes of island tigers may break up into spotted patterns.[11]

This two-subspecies proposal was reaffirmed in 2015 by a comprehensive analysis of morphological, ecological, and molecular traits of all putative tiger subspecies using a combined approach. The authors proposed recognition of only two subspecies, namely P. t. tigris comprising the

In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group revised felid taxonomy in accordance with the two-subspecies proposal of the comprehensive 2015 study, and recognised the tiger populations in continental Asia as P. t. tigris, and those in the Sunda Islands as P. t. sondaica.

The following tables are based on the classification of the species Panthera tigris provided in Mammal Species of the World,[9] and also reflect the classification used by the Cat Classification Task Force in 2017:[14]

| Populations | Description | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Bengal tiger | This tiger inhabits the scientific description of the tiger was based on descriptions by earlier naturalists such as Conrad Gessner and Ulisse Aldrovandi.[2] Bengal tiger skins in the collection of the Natural History Museum, London were described as bright orange-red with shorter fur and more spaced out stripes than northern-living tigers like the Siberian tiger.[8]

|

|

| †Caspian tiger formerly P. t. virgata (Illiger, 1815)[19] | This population lived in west-central Asia, reach as far west as Turkey.[18] Illiger's description was not based on a particular specimen, but he only assumed that tigers in the Caspian area differ from those elsewhere.[19] It was later described having a bright rusty-red coat with thin and closely spaced brownish stripes,[20] and a broad occipital bone.[10] According to genetic analysis, it was closely related to the Siberian tiger.[21] It has been extinct since the 1970s.[22] |

|

| Siberian tiger formerly P. t. altaica (Temminck, 1844)[23] | This tiger lives in the Russian Far East, Northeast China and possibly North Korea.[18] Temminck's description was based on an unspecified number of tiger skins with long hairs and dense coats that were traded between Korea and Japan. He assumed they originated in the Altai Mountains.[23] The Siberian tiger was later described as having an ochre-yellow winter coat that becomes redder and more vibrant after molting. It has black or dark brown stripes, which are fewer in number.[24] The skull is described as shorter and broader then southern-living tigers.[25] |

|

| South China tiger formerly P. t. amoyensis (Hilzheimer, 1905)[26] | This tiger historically lived in south-central China. extinct in wild as there has not been a confirmed sighting since the 1970s.[1]

|

|

| Indochinese tiger formerly P. t. corbetti Mazák, 1968[27] | The tiger occurs on the Indochinese Peninsula.[18] Mazák's description was based on 25 specimens in museum collections that were smaller than tigers from India and had smaller skulls.[27] It was also said to have a darker coat than the Bengal tiger with more stripes; the stripes being narrower and having less "double stripes".[28]

|

|

| Malayan tiger formerly P. t. jacksoni Luo et al., 2004[29] | It was proposed as a distinct subspecies on the basis of |

|

| Populations | Description | Image |

|---|---|---|

| †Javan tiger formerly P. t. sondaica (Temminck, 1944)[23] | Temminck based his description on an unspecified number of tiger skins with short and smooth hair. South Sukabumi, West Java, was found to be genetically similar to hairs of zoological specimens of the Javan tiger in 2022.[30]

|

|

| †Bali tiger formerly P. t. balica (Schwarz, 1912)[31] | Schwarz based his description on a skin and a skull of an adult female tiger from |

|

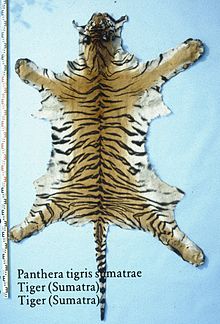

| Sumatran tiger formerly P. t. sumatrae Pocock, 1929[34] | Pocock described a dark skin of a tiger from |

|

Evolution

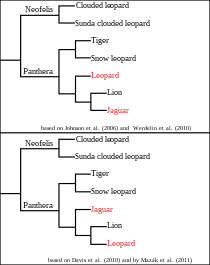

The tiger shares the genus Panthera with the

The fossil species

Results of a

The tiger's full genome sequence was published in 2013. It was found to have repeat compositions much like other cat genomes and "an appreciably conserved synteny".[46]

Hybrids

Captive tigers were bred with lions to create hybrids that share physical and behavioural qualities of both parent species; the liger is the offspring of a female tiger and a male lion, and the tigon the offspring of a male tiger and a female lion.[47] The lion sire passes on a growth-promoting gene, but the corresponding growth-inhibiting gene from the female tiger is absent, so that ligers grow far larger than either parent species. By contrast, the male tiger does not pass on a growth-promoting gene, and the lioness passes on a growth inhibiting gene; hence, tigons are around the same size as either species.[48] Breeding hybrids is considered unethical as they are susceptible to obesity and other birth defects.[47]

Characteristics

The tiger is considered to be the largest living felid species.[11] However, there is some debate over averages compared to the lion. Since tiger populations vary greatly in size, the "average" size for a tiger may be less than a that of a lion, while the biggest tigers are bigger than their lion counterparts.[43] The Siberian and Bengal tigers, along with the extinct Caspian are considered to be the largest of the species.[11] Bengal tigers average a total length of 3 m (9.8 ft), with males weighing 200–260 kg (440–570 lb) and females weighing 100–160 kg (220–350 lb).[49] Island tigers are the smallest; the Sumatran tigers have a total length of 2.2–2.5 m (7 ft 3 in – 8 ft 2 in) with a weight of 100–140 kg (220–310 lb) for males and 75–110 kg (165–243 lb) for females.[49] The extinct Bali tiger was even smaller.[11] It has been hypothesised that body sizes of different tiger populations may be correlated with climate and be explained by thermoregulation and Bergmann's rule.[11][10]

The tiger has a typical felid morphology. It has a muscular body with shortened legs, strong forelimbs, broad paws, a large head and a tail that is about half the length of the rest of its body.[11][50] There are five digits on the front feet and four on the back, all of which have retractable claws that are compact and curved. The ears are rounded, while the eyes have a round pupil.[11] The tiger's skull is large and robust, with a constricted front region, proportionally small, elliptical orbits, long nasal bones, and a lengthened cranium with a large sagittal crest.[51][11] It resembles a lion's skull, with the structure of the lower jaw and length of the nasals being the most reliable indicators for species identification.[51] The tiger has fairly robust teeth and its somewhat curved canines are the longest in the cat family at 6.4–7.6 cm (2.5–3.0 in).[11][52]

Coat

A tiger's coat is generally coarse and relatively thin, though the Siberian tiger has a thick winter coat.[11][53] It has a mane-like heavy growth of fur around the neck and jaws and long whiskers, especially in males.[11] Its colouration is generally orange but can vary from light yellow to dark red.[11][43][54] White fur covers the ventral surface, along with parts of the face.[11][55] It also has a prominent white spot on the back of their ears which are surrounded by black.[11] The tiger is marked with distinctive black or dark brown stripes, the patterns of which are unique for each individual.[11][56] The stripes are mostly vertical, but those on the limbs and forehead are horizontal. They are more concentrated towards the posterior and those on the trunk may or may not reach under the belly. The tips of stripes are generally sharp and some may split up or split and fuse again. Tail stripes are thick bands and a black tip marks the end.[57]

Stripes are likely advantageous for

Colour variations

The three

Pseudo-

Distribution and habitat

The tiger historically ranged from eastern Turkey and northern Afghanistan to Indochina and from southeastern Siberia to Sumatra, Java and Bali.

The tiger mainly lives in forest habitats and is highly adaptable.

Population density

Camera trapping during 2010–2015 in the deciduous and subtropical pine forest of Jim Corbett National Park revealed a stable tiger population density of 12–17 individuals per 100 km2 (39 sq mi) in an area of 521 km2 (201 sq mi).[74] In northern Myanmar, the population density in a sampled area of roughly 3,250 km2 (1,250 sq mi) in a mosaic of tropical broadleaf forest and grassland was estimated to be 0.21–0.44 tigers per 100 km2 (39 sq mi) as of 2009.[75] Population density in mixed deciduous and semi-evergreen forests of Thailand's Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary was estimated at 2.01 tigers per 100 km2 (39 sq mi); during the 1970s and 1980s, logging and poaching had occurred in the adjacent Mae Wong and Khlong Lan National Parks, where population density was much lower, estimated at only 0.359 tigers per 100 km2 (39 sq mi) as of 2016.[76] Population density in

Behaviour and ecology

Camera trap data show that tigers in Chitwan National Park avoided locations frequented by people and were more active at night than during day.[78] In Sundarbans National Park, six radio-collared tigers were most active in the early morning with a peak around dawn and moved an average distance of 4.6 km (2.9 mi) per day.[79] A three-year-long camera trap survey in Shuklaphanta National Park revealed that tigers were most active from dusk until midnight.[80] In northeastern China, tigers were crepuscular and active at night with activity peaking at dawn and dusk; they exhibited a high temporal overlap with ungulate species.[81]

Tigers groom themselves, maintaining their coats by licking them and spreading oil from their sebaceous glands.[82] It will take to water, particularly on hot days. It is a powerful swimmer and easily transverses across rivers as wide as 8 km (5.0 mi).[56] Adults only occasionally climb trees, but have been recorded climbing 10 m (33 ft) up a smooth pipal tree.[11] In general, tigers are less capable tree climbers than many other cats due to their size, but cubs under 16 months old may routinely do so.[83]

Social spacing

Adult tigers lead largely solitary lives. They establish and maintain

The tiger is a long-ranging species, and individuals

Male tigers are generally less tolerant of other males within their home ranges than females are of other females. Disputes are usually solved by intimidation rather than outright violence. Once

Communication

During friendly encounters and bonding, tigers rub against each other's bodies.[100] Facial expressions include the "defence threat", which involves a wrinkled face, bared teeth, pulled-back ears, and widened pupils.[100][11] Both males and females show a flehmen response, a characteristic grimace, when sniffing urine markings. Males also use the flehman to detect the markings made by tigresses in oestrus.[11] Tigers also use their tails to signal their mood. To show cordiality, the tail sticks up and sways slowly, while an apprehensive tiger lowers its tail or wags it side-to-side. When calm, the tail hangs low.[101]

Tigers are normally silent but can produce numerous vocalisations.[102][103] They roar to signal their presence to other individuals over long distances. This vocalisation is forced through an open mouth as it closes and can be heard 3 km (1.9 mi) away. A tiger may roar three or four times in a row, and others may respond in kind. Tigers also roar during mating, and a mother will roar to call her cubs to her. When tense, tigers will moan, a sound similar to a roar but softer and made when the mouth is at least partially closed. Moaning can be heard 400 m (1,300 ft) away.[11][104]

Aggressive encounters involve

Hunting and diet

The tiger is a carnivore and an apex predator feeding mainly on ungulates, with a particular preference for sambar deer, Manchurian wapiti, barasingha and wild boar. Tigers kill large ungulates like gaur[110] and opportunistically, smaller prey like monkeys, peafowl and other ground-based birds, porcupines and fish.[11][56] Occasional attacks on Asian elephants and Indian rhinoceros have also been reported.[111]

More often, tigers take the more vulnerable small calves.

Tigers learn to hunt from their mothers, which is important but not necessary for their success.[114] Depending on the prey, a tiger typically kills weekly though mothers must kill more often.[49] They usually hunt alone, but families hunt together when cubs are old enough.[115] A tiger travels up to 19.3 km (12.0 mi) per day in search of prey, using vision and hearing to find a target.[116] It also waits at a watering hole for prey to come by, particularly during hot summer days.[117][118] It is an ambush predator and when approaching potential prey, the tiger crouches with its head lowered and hides in foliage. It switches between creeping forward and staying still. Tigers have been recorded dozing off while in still mode and can stay in the same spot for as long as a day, waiting for prey, and launch an attack when the prey is close enough,[119] usually within 30 m (98 ft).[49] If the prey spots it before then, the cat does not pursue further.[117] Tigers can sprint 56 km/h (35 mph) and leap 10 m (33 ft);[120][121] they are not long-distance runners and give up a chase if prey outpaces them over a certain distance.[117]

The tiger attacks from behind or at the sides and tries to knock the target off balance. It latches onto prey with its forelimbs, twisting and turning during the struggle. The tiger generally applies a

The tiger typically moves its kill to a private, usually vegetated spot no further than 183 m (600 ft), though they have been recorded dragging it 549 m (1,801 ft). The tiger has the strength to drag the carcass of a fully grown buffalo for some distance, a feat three men struggle with. It rests for a while before eating and can consume as much as 50 kg (110 lb) of meat in one session, but feeds on a carcass for several days, leaving very little for scavengers.[128]

Enemies and competitors

Tigers sometimes kill sympatric predators.[129][130] In much of their range, tigers share habitat with leopards and dholes and typically dominate both of them, though large dhole packs can drive away a tiger[131] or even kill it.[132] Tigers appear to inhabit the deep parts of a forest while these smaller predators are pushed closer to the fringes.[133] The three predators coexist by hunting different prey.[134] In one study, tigers were found to have killed prey that weighed an average of 91.5 kg (202 lb), in contrast to 37.6 kg (83 lb) for the leopard and 43.4 kg (96 lb) for the dhole.[135] Leopards can live successfully in tiger habitat when there is abundant food and vegetation cover and no evidence of competitive exclusion.[134][136] Nevertheless, leopards avoid areas where tigers roam and are less common where tigers are numerous.[129][137][138]

Tigers tend to be wary of sloth bears, with their sharp claws, quickness and ability to stand on two legs. Tigers sometimes prey on sloth bears by ambushing them when they are feeding at termite mounds.[139] Siberian tigers attack, kill and prey on Ussuri brown and black bears.[11] Brown bears frequently track down tigers to usurp their kills, with occasional fatal outcomes for the tiger.[140][141]

Reproduction and life cycle

The tiger

A tigress gives birth in a secluded location, be it in dense vegetation, in a cave or under a rocky shelter.[146] Litters consist of as many as seven cubs, but two or three are more typical.[142][146] Newborn cubs weigh 785–1,610 g (27.7–56.8 oz), and are blind and altricial.[146] The mother licks and cleans her cubs, suckles them and viscously defends them from any potential threat.[142] She will only leave them alone to hunt, and even then she does not travel far.[147] When a mother suspects an area is no longer safe, she moves her cubs to a new spot, transporting them one by one by grabbing them by the scruff of the neck with her mouth. The mortality rate for tiger cubs can reach 50% during these early months; causes of death include predators like dholes, leopards and pythons.[148] Young are able to see in a week, can leave the denning site in two months and around the same time they start eating meat.[142][149]

After around two months, the cubs are able to follow their mother. They still hide in vegetation when she goes hunting, and she will guide them to the kill. Cubs bond through play fighting and practice stalking. A hierarchy develops in the litter, with the biggest cub, often a male, being the most dominant and the first to eat its fill at a kill.[150] Around the age of six months, cubs are fully weaned and have more freedom to explore their environment. Between eight and ten months, they accompany their mother on hunts.[148] A cub can make a kill as early as 11 months and reach independence around 18 to 24 months of age; males become independent earlier than females.[151] Radio-collared tigers in Chitwan started dispersing from their natal areas at the age of 19 months.[93] Young females are sexually mature at three to four years, whereas males are at four to five years.[11]

Generation length of the tiger is about 7–10 years.[152]

Wild Bengal tigers live 12–15 years.

The father does not play a role in raising the young, but he encounters and interacts with them. The resident male appears to visit the female–cub families within his home range. They socialise and even share kills.[155][156] One male was recorded looking after orphaned cubs whose mother had died.[157] By defending his home range, the male protects the females and cubs from other males.[158] When a new male takes over, dependent cubs are at risk of being killed, as the male attempts to sire his own young with the females. Older female cubs are tolerated but males are treated as potential competitors.[159]

Health and diseases

Tigers are recorded as hosts for various parasites including

Threats

The tiger has been listed as

Protected areas in central India are highly fragmented due to linear infrastructure like roads, railway lines, transmission lines, irrigation channels and mining activities in their vicinity.[163] In the Tanintharyi Region of southern Myanmar, deforestation coupled with mining activities and high hunting pressure threatens the tiger population in the area.[164] In Thailand, nine of 15 protected areas hosting tigers are isolated and fragmented offering a low probability for dispersal between them; and four of these do not harbour tigers any more at least since 2013.[165] In Peninsular Malaysia, 8,315.7 km2 (3,210.7 sq mi) of tiger habitat was cleared during 1988–2012, most of it for industrial plantations.[166] Large-scale land acquisitions of about 23,000 km2 (8,900 sq mi) for commercial agriculture and timber extraction in Cambodia contributed to the fragmentation of potential tiger habitat, especially in the Eastern Plains.[167] Inbreeding depression coupled with habitat destruction, insufficient prey resources and poaching is a threat to the small and isolated tiger population in the Changbai Mountains along the China–Russia border.[168] In China, tigers became the target of large-scale 'anti-pest' campaigns in the early 1950s, where suitable habitats were fragmented following deforestation and resettlement of people to rural areas, who hunted tigers and prey species. Though tiger hunting was prohibited in 1977, the population continued to decline and is considered extinct in South China since 2001.[169][170]

Tiger populations in India have been targeted by poachers since the 1990s and were extirpated in two tiger reserves in 2005 and 2009.[171] Between March 2017 and January 2020, 630 activities of hunters using snares, drift nets, hunting platforms and hunting dogs were discovered in a reserve forest of about 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi) in southern Myanmar.[172] Nam Et-Phou Louey National Park was considered the last important site for the tiger in Laos, but it has not been recorded there at least since 2013; this population likely fell victim to indiscriminate snaring.[173] Anti-poaching units in Sumatra's Kerinci Seblat landscape removed 362 tiger snare traps and seized 91 tiger skins during 2005–2016; annual poaching rates increased with rising skin prices.[174] Poaching is also the main threat to the tiger population in far eastern Russia, where logging roads facilitate access for poachers and people harvesting forest products that are vital for prey species to survive in winter.[175]

Body parts of 207 tigers were detected during 21 surveys in 1991–2014 in two wildlife markets in Myanmar catering to customers in Thailand and China.[176] During the years 2000–2022, at least 3,377 tigers were confiscated in 2,205 seizures in 28 countries; seizures encompassed 665 live and 654 dead individuals, 1,313 whole tiger skins, 16,214 body parts like bones, teeth, paws, claws, whiskers, and 1.1 t (1.1 long tons; 1.2 short tons) of meat; 759 seizures in India encompassed body parts of 893 tigers; and 403 seizures in Thailand involved mostly captive-bred tigers.[177] Seizures in Nepal between January 2011 and December 2015 included 585 pieces of tiger body parts and two whole bodies in 19 districts.[178] Seizure data from India during 2001–2021 indicate that tiger skins were the most often traded body parts, followed by claws, bones and teeth; trafficking routes mainly passed through the states of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Assam.[179] A total of 292 illegal tiger parts were confiscated at US ports of entry from personal baggage, air cargo and mail between 2003 and 2012.[180]

Demand for tiger parts for use in traditional Chinese medicine has also been cited as a major threat to tiger populations.[181] Interviews with local people in the Bangladeshi Sundarbans revealed that they kill tigers for local consumption and trade of skins, bones and meat, in retaliation for attacks by tigers, and for excitement.[182] Tiger body parts like skins, bones, teeth and hair are consumed locally by wealthy Bangladeshis and are illegally trafficked from Bangladesh to 15 countries including India, China, Malaysia, Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, Japan and the United Kingdom via land borders, airports and seaports.[183] Tiger bone glue is the prevailing tiger product purchased for medicinal purposes in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.[184]

Local people killing tigers in

Conservation

| Country | Year | Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 3,167–3,682[190] | |

| 2022 | 573–600[191] | |

| 2022 | 393[191] | |

| 2022 | 316–355[192] | |

| 2022 | 148–189[191] | |

| 2022 | 131[193] | |

| 2022 | <150[191] | |

| 2018 | 114[191] | |

| 2022 | >60[191] | |

| 2022 | 28[191] | |

| Total | 5,634–5,891 |

Internationally, the tiger is protected under CITES Appendix I, banning trade of live tigers and their body parts.[1] In Russia, hunting the tiger has been banned since 1952.[194] In Bhutan, it has been protected since 1969 and enlisted as totally protected since 1995.[195] Since 1972, it has been afforded the highest protection level under India's Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972.[196] In Nepal and Bangladesh, it has been protected since 1973.[196][183] Since 1976, it has been totally protected under Malaysia's Protection of Wild Life Act.[197] In Indonesia, it has been protected since 1990.[198] In China, the trade in tiger body parts was banned in 1993.[199]

In 1973, the National Tiger Conservation Authority and Project Tiger were founded in India to gain public support for tiger conservation.[171] Since then, 53 tiger reserves covering an area of 75,796 km2 (29,265 sq mi) have been established in the country until 2022.[190] Myanmar's national tiger conservation strategy developed in 2003 comprises management tasks such as restoration of degraded habitats, increasing the extent of protected areas and wildlife corridors, protecting tiger prey species, thwarting tiger killing and illegal trade of its body parts, and promoting public awareness through wildlife education programmes.[200] Bhutan's first Tiger Action Plan implemented during 2006–2015 revolved around habitat conservation, human–wildlife conflict management, education and awareness; the second Action Plan aimed at increasing the country's tiger population by 20% until 2023 compared to 2015.[195] In 2009, the Bangladesh Tiger Action Plan was initiated to stabilise the country's tiger population, maintain habitat and a sufficient prey base, improve law enforcement and foster cooperation between governmental agencies responsible for tiger conservation.[201] The Thailand Tiger Action Plan

In 2010, representatives of the tiger range countries agreed to double tiger populations.[191] The Thai Wildlife Preservation and Protection Act was enacted in 2019 to combat poaching and trading of body parts.[205] In 2010, Malaysia passed the Wildlife Conservation Act which increased punishments for wildlife-related crimes and has used its army and police for help in patrolling. Nearly all tiger habitat in the country are managed as one unit under the Central Forest Spine initiative.[191]

Increases in anti-poaching patrol efforts in four Russian protected areas during 2011–2014 contributed to reducing poaching, stabilising the tiger population and improving protection of ungulate populations.[206] Poaching and trafficking were declared to be moderate and serious crimes in 2019.[191] Anti-poaching operations were also established in Nepal in 2010, with increased cooperation and intelligence sharing between agencies. These policies have led to many years of "zero poaching" and the country's tiger population has doubled in a decade.[191] Anti-poaching patrols in the 1,200 km2 (460 sq mi) large core area of Taman Negara lead to a decrease of poaching frequency from 34 detected incidents in 2015–2016 to 20 incidents during 2018–2019; the arrest of seven poaching teams and removal of snares facilitated the survival of three resident female tigers and at least 11 cubs.[207]

Wildlife corridors are also important for tiger conservation as they allow for connectivity between populations outside protected areas. Tigers were found to use at least nine corridors that were established between protected areas in the Terai Arc Landscape and Sivalik Hills in both Nepal and India.[208] Corridors in forested areas with low human encroachment are highly suitable.[209][210] In West Sumatra, 12 wildlife corridors were identified as high priority for mitigating human–wildlife conflicts.[211] In 2019, China and Russia signed a memorandum of understanding for transboundary cooperation between two protected areas, Northeast China Tiger and Leopard National Park and Land of the Leopard National Park, that includes the creation of wildlife corridors and bilateral monitoring and patrolling along the Sino-Russian border.[212]

Rescued and rehabilitated problem tigers and orphaned tiger cubs have been released into the wild and monitored in India, Sumatra and Russia.[86][89][213] In Kazakhstan, habitat restoration and reintroduction of prey species in Ile-Balkash Nature Reserve have progressed, and tiger reintroduction is planned for 2025.[214] Reintroduction of tigers is considered possible in eastern Cambodia, once management of protected areas is improved and forest loss stabilized.[215] Tigers are kept and bred in China, with plans to reintroduce their offspring into remote protected areas.[17][114]

Relationship with humans

Hunting

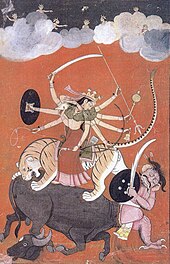

A tiger hunt painted on the

Attacks

Tigers are said to have directly killed more people than any other wild mammal.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the

Tiger attacks in the Sundarbans caused 1,396 human deaths in the period 1935–2006 according to official records of the Bangladesh Forest Department.[228] Victims of attacks are local villagers who enter the tiger's domain to collect resources like wood and honey. Fishermen have been particularly common targets. Methods to counter tiger attacks have included face masks worn backwards, protective clothes, sticks and carefully stationed electric dummies.[229]

Captivity

Tigers have been kept in captivity since ancient times. In ancient Rome, tigers were displayed in amphitheatres; they were slaughtered in venatio hunts and used for public executions of criminals. Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan is reported to have kept tigers in the 13th century. Starting in the Middle Ages, tigers were being kept in European menageries. In 1830, two tigers and a lion were accidentally put in the same exhibit at the Tower of London. This led to a fight between them and, after they were separated, the lion died of its wounds.[230] Tigers and other exotic animals were mainly used for the entertainment of elites but from the 19th century onward, they were exhibited more to the public. Tigers were particularly big attractions, and their captive population soared.[231] Captive tigers may display stereotypical behaviours such as pacing or inactivity. Zoos are able to reduce such behaviours with exhibits designed so the animals can move between separate but connected enclosures.[232] Enrichment items are also important for the cat's welfare and the stimulation of its natural behaviours.[233]

Tigers have played prominent roles in circuses and other live performances. Ringling Bros included many tiger tamers in the 20th century including Mabel Stark, who became a big draw and had a long career. She was well known for being able to control the tigers despite being a small woman; using "manly" tools like whips and guns. Another trainer was Clyde Beatty, who used chairs, whips and guns to provoke tigers and other beasts into acting fierce and allowed him to appear courageous. He would perform with as many as 40 tigers and lions in one act. From the 1960s onward, trainers like Gunther Gebel-Williams would use gentler methods to control their animals. Tiger trainer Sara Houckle was dubbed "the Tiger Whisperer" as she trained the cats to obey her by whispering to them.[234] Siegfried & Roy became famous for performing with white tigers in Las Vegas. The act ended in 2003 when a tiger attacked Roy during a performance.[235] The use of tigers and other animals in shows would eventually decline in many countries due to pressure from animal rights groups and greater desires from the public to see them in more natural settings. Several countries restrict or ban such acts.[236] As of 2009, tigers were the most traded circus animals.[237]

Tigers have become popular in the exotic pet trade, particularly in the United States,[238] where 5,000 tigers were estimated to have been kept in captivity in 2020, with only 6% of them being in zoos and other facilities approved by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Private collectors are thought to be ill-equipped to provide proper care for tigers, which compromises their welfare. They can also threaten public safety by allowing people to interact with them.[239] The keeping of tigers and other big cats by private people was banned in the US in 2022.[240] About 7,000–8,000 tigers were held in "tiger farm" facilities in China and Southeast Asia as of 2020; these tigers are bred to be used for traditional medicine and appear to pose a threat to wild populations by rising demand for tiger parts.[239]

Cultural significance

The tiger is among the most famous of the charismatic megafauna. It has been labelled as "a rare combination of courage, ferocity and brilliant colour".[142] In a 2004 online poll conducted by cable television channel Animal Planet, involving more than 50,000 viewers from 73 countries, the tiger was voted the world's favourite animal with 21% of the vote, narrowly beating the dog.[241] Likewise, a 2018 study found the tiger to be the most popular wild animal based on surveys, as well as appearances on websites of major zoos and posters of some animated movies.[242]

While the lion represented royalty and power in

Tigers have had religious and folkloric significance. In

William Blake's 1794 poem "The Tyger" portrays the animal as the duality of beauty and ferocity. It is the sister poem to "The Lamb" in Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience and he ponders why God would create such different creatures. The tiger is featured in the mediaeval Chinese novel Water Margin, where the cat battles and is slain by the bandit Wu Song, while the tiger Shere Khan in Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book (1894) is the mortal enemy of the human protagonist Mowgli. The image of the friendly tame tiger has also existed in culture, notably Tigger, the Winnie-the-Pooh character and Tony the Tiger, the Kellogg's cereal mascot.[250]

See also

- List of largest cats

- San Francisco Zoo tiger attacks

- Tiger King, a 2020 crime documentary series on the exotic pet trade

- Tiger Temple

References

- ^ . Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis tigris". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 41.

- ^ Ellerman, J.R.; Morrison-Scott, T.C.S. (1951). "Panthera tigris, Linnaeus, 1758". Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946. London: British Museum. p. 318.

- ^ Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (1940). "τίγρις". A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Varro, M. T. (1938). "XX. Ferarum vocabula" [XX. The names of wild beasts]. De lingua latina [On the Latin language]. Translated by Kent, R. G. London: W. Heinemann. pp. 94–97.

- S2CID 165388712.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1929). "Tigers". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 33 (3): 505–541.

- ^ a b Pocock, R. I. (1939). "Panthera tigris". The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia: Volume 1. London: T. Taylor and Francis, Ltd. pp. 197–210.

- ^ OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c Kitchener, A. "Tiger distribution, phenotypic variation and conservation issues" in Seidensticker, Christie & Jackson 1999, pp. 19–39

- ^ JSTOR 3504004.

- PMID 26601191.

- ^ .

- ^ a b c d Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 66–68.

- PMID 30482605.

- PMID 33592092.

- ^ PMID 37069598.

- ^ ISBN 2-8317-0045-0.

- ^ a b Illiger, C. (1815). "Überblick der Säugethiere nach ihrer Verteilung über die Welttheile". Abhandlungen der Königlichen Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. 1804–1811: 39–159. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Sludskii 1992, p. 137.

- PMID 19142238.

- ^ a b c Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S.; Jackson, P. "Preface" in Seidensticker, Christie & Jackson 1999, pp. xv–xx

- ^ a b c d Temminck, C. J. (1844). "Aperçu général et spécifique sur les Mammifères qui habitent le Japon et les Iles qui en dépendent". In Siebold, P. F. v.; Temminck, C. J.; Schlegel, H. (eds.). Fauna Japonica sive Descriptio animalium, quae in itinere per Japoniam, jussu et auspiciis superiorum, qui summum in India Batava imperium tenent, suscepto, annis 1825–1830 collegit, notis, observationibus et adumbrationibus illustravit Ph. Fr. de Siebold. Leiden: Lugduni Batavorum.

- ^ Sludskii 1992, pp. 131, 134.

- ^ .

- ^ a b Hilzheimer, M. (1905). "Über einige Tigerschädel aus der Straßburger zoologischen Sammlung". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 28: 594–599.

- ^ S2CID 84054536.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 15583716.

- .

- ^ .

- ISBN 978-3-89432-759-0.

- Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 43 (2): 108–113.

- ^ a b Pocock, R. I. (1929). "Tigers". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 33: 505–541.

- ^ S2CID 41672825.

- ISBN 978-0-19-923445-5. Archivedfrom the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ]

- ^ PMID 22016768.

- PMID 20138224.

- PMID 24225466.

- S2CID 257842190.

- S2CID 246693903.

- ^ a b c Kitchener, A. & Yamaguchi, N. (2009). "What is a Tiger? Biogeography, Morphology, and Taxonomy" in Tilson & Nyhus 2010, pp. 53–84

- PMID 35892215.

- .

- PMID 24045858.

- ^ .

- ^ "Genomic Imprinting". Genetic Science Learning Center, Utah.org. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sunquist, M. (2010). "What is a Tiger? Ecology and Behaviour" in Tilson & Nyhus 2010, pp. 19−34

- ^ Sludskii 1992, p. 98.

- ^ a b Sludskii 1992, p. 103.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Sludskii 1992, p. 99.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Sludskii 1992, pp. 100–102.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Miquelle, D. "Tiger" in Macdonald 2001, pp. 18–21

- ^ Sludskii 1992, pp. 99–102.

- .

- .

- PMID 20961899.

- PMID 31138092.

- PMID 28281538.

- ^ Xavier, N. (2010). "A new conservation policy needed for reintroduction of Bengal tiger-white" (PDF). Current Science. 99 (7): 894–895.

- PMID 34518374.

- ^ .

- ^ Sludskii 1992, pp. 108–112.

- ^ Miquelle, D. G.; Smirnov, E. N.; Merrill, T. W.; Myslenkov, A. E.; Quigley, H.; Hornocker, M. G. & Schleyer, B. (1999). "Hierarchical spatial analysis of Amur tiger relationships to habitat and prey" in Seidensticker, Christie & Jackson 1999, pp. 71–99

- ^ Wikramanayake, E. D.; Dinerstein, E.; Robinson, J. G.; Karanth, K. U.; Rabinowitz, A.; Olson, D.; Mathew, T.; Hedao, P.; Connor, M.; Hemley, G. & Bolze, D. (1999). "Where can tigers live in the future? A framework for identifying high-priority areas for the conservation of tigers in the wild" in Seidensticker, Christie & Jackson 1999, pp. 254–272

- ^ Jigme, K. & Tharchen, L. (2012). "Camera-trap records of tigers at high altitudes in Bhutan". Cat News (56): 14–15.

- .

- PMID 37464931.

- .

- PMID 22087218.

- .

- .

- doi:10.1111/csp2.560.

- .

- PMID 22949642.

- PMID 27049644.

- S2CID 92446020.

- S2CID 92736301.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Thapar 2004, pp. 26, 65–66.

- ^ .

- .

- ^ S2CID 254187854.

- .

- .

- ^ a b Priatna, D.; Santosa, Y.; Prasetyo, L. B. & Kartono, A. P. (2012). "Home range and movements of male translocated problem tigers in Sumatra" (PDF). Asian Journal of Conserviation Biolology. 1 (1): 20–30.

- .

- PMID 24223132.

- ^ a b Thapar 2004, p. 76.

- ^ .

- S2CID 5558760.

- S2CID 53149100.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 105.

- ^ Mills 2004, p. 85–86.

- ^ Schaller 1967, pp. 244–251.

- ^ Mills 2004, p. 89.

- ^ a b Schaller 1967, p. 263.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Schaller 1967, p. 256.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 99.

- ^ Schaller 1967, pp. 258–261.

- ^ a b Schaller 1967, p. 261.

- S2CID 25252052.

- ^ Schaller 1967, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Schaller 1967, pp. 256–258.

- ^ Mills 2004, p. 62.

- .

- ^ Karanth, K. U. (2003). "Tiger ecology and conservation in the Indian subcontinent" (PDF). Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 100 (2 & 3): 169–189.

- JSTOR 176521.

- ASIN B0007DU2IU.

- ^ hdl:2263/50208.

- ^ Thapar 2004, pp. 63, 111.

- ^ Schaller 1967, pp. 284–285.

- ^ a b c Schaller 1967, p. 288.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 120.

- ^ Thapar 2004, pp. 119–120, 122.

- ^ Schaller 1967, p. 287.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 23.

- ^ a b Thapar 2004, p. 121.

- ^ Schaller 1967, p. 295.

- .

- ^ Schaller 1967, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 126.

- ^ Schaller 1967, p. 289.

- ^ Schaller 1967, pp. 297–300.

- ^ a b Schaller 1967, p. 277.

- ^ McDougal, C. (1988). "Leopard and tiger interactions at Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 85 (3): 609–610.

- S2CID 259903849.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 136.

- .

- ^ .

- JSTOR 5647.

- .

- JSTOR 2989714.

- .

- ^ Mills 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Seryodkin, I. V. (2007). "Роль бурого медведя в экосистемах Дальнего Востока России" [The role of the brown bear in the ecosystems of the Russian Far East]. In Dvoretsky, А. N.; A. V. Ivashov, А. V.; Koshelev, А. I.; Novitsky, R. А.; Serebryakov, V. V. (eds.). Биоразнообразие и роль животных в экосистемах: Материалы IV Международной научной конференции [Biodiversity and the role of animals in ecosystems: Proceedings of the IV International Scientific Conference] (in Russian). Dnepropetrovsk: National University of Dnepropetrovsk. pp. 502–503. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- .

- ^ .

- ^ a b c Mills 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 145.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Thapar 2004, p. 45.

- ^ Mills 2004, p. 50.

- ^ a b Thapar 2004, p. 51.

- ^ Mills 2004, p. 50–51.

- ^ Mills 2004, pp. 61, 66–67.

- ^ Schaller 1967, pp. 270, 276.

- .

- doi:10.61186/JAD.2023.5.3.5 (inactive 24 April 2024).)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link - PMID 33861886.

- ^ Mills 2004, pp. 59, 89.

- ^ Thapar 2004, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Pandey, G. (2011). "India male tiger plays doting dad to orphaned cubs". BBC News. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Mills 2004, pp. 59.

- ^ Thapar 2004, pp. 66–67.

- PMID 23943758.

- PMID 20966275.

- PMID 33822151.

- PMID 35288989.

- .

- .

- hdl:1903/31503.

- .

- PMID 36881515.

- .

- .

- ^ .

- hdl:11250/3040580.

- .

- .

- .

- .

- ^ Wong, R. & Krishnasamy, K. (2022). Skin and Bones: Tiger Trafficking Analysis from January 2000 – June 2022 (PDF). Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia: TRAFFIC, Southeast Asia Regional Office.

- doi:10.1111/csp2.247.

- PMID 35431409.

- doi:10.1111/csp2.622.

- ^ Van Uhm, D. P. (2016). The Illegal Wildlife Trade: Inside the World of Poachers, Smugglers and Traders (Studies of Organized Crime). New York: Springer.

- .

- ^ .

- .

- .

- doi:10.4137/EHI.S24 (inactive 10 April 2024).)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link - hdl:1887/57668.

- .

- hdl:10356/165557.

- ^ a b Qureshi, Q.; Jhala, Y. V.; Yadav, S. P. & Mallick, A. (2023). Status of tigers, co-predators and prey in India 2022 (PDF). New Delhi, Dehradun: National Tiger Conservation Authority & Wildlife Institute of India.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Global Tiger Recovery Program (2023–34) (Report). Global Tiger Forum and the Global Tiger Initiative Council. 2023.

- ^ DNPWC & DFSC (2022). Status of Tigers and Prey in Nepal 2022 (PDF). Kathmandu, Nepal: Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation and Department of Forests and Soil Conservation. Ministry of Forests and Environment.

- ^ Department of Forests and Park Services (2023). "National Tiger Survey 2021–22". Thimphu: Government of Bhutan.

- ^ Sludskii 1992, p. 202.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 99933-673-4-6.

- ^ Malaysian Conservation Alliance for Tigers (2006). The Malayan Tiger Conservation Programme (PDF) (Report). Kuala Lumpur: Department of Wildlife and National Parks Peninsular Malaysia.

- ^ Ministry of Forestry (2007). Conservation Strategy and Action Plan for the Sumatran Tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) Indonesia 2007-2017 (PDF). Government of Indonesia.

- .

- PMID 16362487.

- .

- ^ Pisdamkham, C.; Prayurasiddhi, T.; Kanchanasaka, B.; Maneesai, R.; Simcharoen, S.; Pattanavibool, A.; Duangchantrasiri, S.; Simcharoen, A.; Pattanavibool, R.; Maneerat, S.; Prayoon, U.; Cutter, P. G. & Smith, J. L. D. (2010). Thailand Tiger Action Plan 2010–2022. Bangkok: Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

- ^ Chandradewi, D. S.; Semiadi, G.; Pinondang, I.; Kheng, V. & Bahaduri, L. D. (2019). "A decade on: The second collaborative Sumatra-wide Tiger survey". Cat News. 69: 41–42.

- ^ Wibisono, H. T. (2021). An Island-wide Status of Sumatran Tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) and Principal Prey in Sumatra, Indonesia (Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology and Wildlife Ecology). Delaware: University of Delaware.

- ^ Kampongsun, S. (2022). "The future of Panthera tigris in Thailand and globally". IUCN. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- PMID 26458501.

- .

- PMID 37261321.

- .

- doi:10.1007/s10666-024-09966-w.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bibcode (link - .

- ^ Paudyal, B. N. (2023). Evaluation of the project on transboundary cooperation on the conservation of Amur tigers, Amur leopards and Snow leopards in North-East Asia (PDF) (Report). Bangkok, Thailand: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific.

- .

- .

- .

- ^ Thapar 2004, pp. 186–193.

- ISBN 0195677285.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 193.

- S2CID 238134573.

- ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- ^ a b Nyhus, P. J. & Tilson, R. (2010). "Panthera tigris vs Homo sapiens: Conflict, coexistence, or extinction?" in Tilson & Nyhus 2010, pp. 125–142

- ^ PMID 21392348.

- ^ Mills 2004, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 276.

- ^ Green 2006, pp. 73–74.

- JSTOR 24810674.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 274.

- doi:10.2461/wbp.2013.9.6 (inactive 19 April 2024).)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link - ^ Mills 2004, pp. 111–113.

- ^ Thapar 2004, pp. 173, 179–180.

- ^ Green 2006, pp. 126–130.

- PMID 36478300.

- PMID 29165868.

- ^ Thapar 2004, pp. 202–204.

- ^ Green 2006, p. 140.

- ^ Thapar 2004, pp. 204–205.

- S2CID 32259865.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 214.

- ^ a b Henry, L. (2020). "5 Things Tiger King Doesn't Explain About Captive Tigers". World Wildlife. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ "June 18 Deadline for Compliance With Big Cat Public Safety Act". fws.gov. 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ "Endangered tiger earns its stripes as the world's most popular beast". The Independent. 2004. Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- PMID 29985962.

- ^ ISBN 978-0826419132.

- ^ Green 2006, pp. 39, 46.

- ^ Thapar 2004, pp. 156, 164.

- ISBN 978-1-85538-118-6.

- ^ Green 2006, pp. 60, 86–88, 96.

- ^ Green 2006, p. 96.

- ^ Thapar 2004, p. 152.

- ^ Green 2006, pp. 72–73, 78, 125–127, 147–148.

Bibliography

- ISBN 1-59315-024-5.

- Green, S. (2006). Tiger. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-276-8.

- MacDonald, D., ed. (2001). The Encyclopedia of Mammals (Second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-7607-1969-5.

- Tilson, R.; Nyhus, P. J., eds. (2010). Tigers of the World: The Science, Politics and Conservation of Panthera tigris (Second ed.). London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-094751-8.

- Mills, S. (2004). Tiger. Richmond Hill: Firefly Books. ISBN 1-55297-949-0.

- ISBN 0-226-73631-8.

- Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S.; Jackson, P., eds. (1999). Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in Human-Dominated Landscapes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521648356.

- Sludskii, A. A. (1992). "Tiger Panthera tigris Linnaeus, 1758". In Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (eds.). Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union]. Vol. II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats) (Second ed.). Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 95–202. ISBN 978-90-04-08876-4.

External links

Media related to Panthera tigris (category) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Panthera tigris (category) at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Panthera tigris at Wikispecies

Data related to Panthera tigris at Wikispecies Quotations related to Tigers at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Tigers at Wikiquote Tigers travel guide from Wikivoyage

Tigers travel guide from Wikivoyage- "Tiger Panthera tigris". IUCN/SSCCat Specialist Group.