Timucua

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Extinct as a tribe | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Timucua | |

| Religion | |

| Native; Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Numerous internal chiefdoms, 11 dialects |

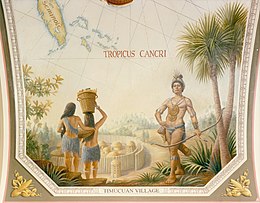

The Timucua were a

The name "Timucua" (recorded by the French as Thimogona but this is likely a misprint for Thimogoua) came from the

While alliances and confederacies arose between the chiefdoms from time to time, the Timucua were never organized into a single political unit.

Meaning

The word "Timucuan" may derive from "Thimogona" or "Tymangoua", an

History

The Timucua were organized into as many as 35 chiefdoms, each of which had hundreds of people in assorted villages within its purview. They sometimes formed loose political alliances, but did not operate as a single political unit.

Timucua tribes, in common with other peoples in Florida, engaged in limited warfare with each other. The standard pattern was to raid a town by surprise, kill and scalp as many men of the town as possible during the battle, and carry away any women and children that could be captured. The victors in such battles did not try to pursue their defeated enemies, and there were no prolonged campaigns. Laudonnière reported that after a successful raid a tribe would celebrate its victory for three days and nights.[8]

The Timucua may have been the first

Later, in 1528, Pánfilo de Narváez's expedition passed along the western fringes of the Timucua territory.[10]

In 1539, Hernando de Soto led an army of more than 500 men through the western parts of Timucua territory, stopping in a series of villages of the Ocale, Potano, Northern Utina, and Yustaga branches of the Timucua on his way to the Apalachee domain (see list of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition for other sites visited by de Soto). His army seized the food stored in the villages, forced women into concubinage, and forced men and boys to serve as guides and bearers. The army fought two battles with Timucua groups, resulting in heavy Timucua casualties. After defeating the resisting Timucuan warriors, Hernando de Soto had 200 executed, in what was to be called the Napituca Massacre, the first large-scale massacre by Europeans on what later became U.S. soil (Florida).[11] De Soto was in a hurry to reach the Apalachee domain, where he expected to find gold and sufficient food to support his army through the winter, so he did not linger in Timucua territory.[12][13][page needed] The Acuera resisted the Spaniards de Soto's forces when de Soto's forces tried to seize stored food from Acuera towns, killing several of the Spaniards.[14][15]

In 1564, French

The Timucua history changed after the Spanish established

By 1700, the Timucuan population had been reduced to just 1,000. In 1703, Governor

A census in 1711 found 142 Timucua-speakers living in four villages under Spanish protection.[16] Another census in 1717 found 256 people in three villages where Timucua was the language of the majority, although there were a few inhabitants with a different native language.[17] The population of the Timucua villages was 167 in 1726.[18] By 1759 the Timucua under Spanish protection and control numbered just six adults and five half-Timucua children.[19]

In 1763, when Spain ceded Florida to Great Britain, the Spanish took the less than 100 Timucua and other natives to Cuba. Research is underway in Cuba to discover if any Timucua descendants exist there. Some historians believe a small group of Timucua may have stayed behind in Florida or Georgia and possibly assimilated into other groups such as the Seminoles. Many Timucua artifacts are stored at the Florida Museum of Natural History, the University of Florida and in other museums.[20][permanent dead link]

Tribes

The Timucua were divided into a number of different tribes or chiefdoms, each of which spoke one of the nine or ten dialects of the Timucua language. The tribes can be placed into eastern and western groups. The Eastern Timucua were located along the Atlantic coast and on the Sea Islands of northern Florida and southeastern Georgia; along the St. Johns River and its tributaries; and among the rivers, swamps and associated inland forests in southeastern Georgia, possibly including the Okefenokee Swamp. They usually lived in villages close to waterways, participated in the St. Johns culture or in unnamed cultures related to the Wilmington-Savannah culture, and were more focused on exploiting the resources of marine and wetland environments.[21][22][23][24] All of the known Eastern Timucua tribes were incorporated into the Spanish mission system starting in the late 16th century.[25]

The Western Timucua lived in the interior of the upper Florida peninsula, extending to the Aucilla River on the west and into Georgia to the north. They usually lived in villages in hammocks, and participated in the Alachua, Suwannee Valley or other unknown cultures. Because of their environment, they were more oriented to exploiting the resources of the hammocks.[21]

Early 20th-century scholars such as

A chiefdom in central Florida (in southeastern Lake or southwestern Orange counties) led by Urriparacoxi may have spoken Timucua. "Urriparacoxi" was a Timucuan term for "war-prince".[28] While leadership titles were borrowed between different languages in what is now the southeastern United States, "Urriparacoxi" is not known to have been used by any group that did not speak Timucuan.[29]

Based on a vocabulary list collected from a man named Lamhatty in 1708, Swanton classified the Tawasa language as a dialect of Timucuan. Later scholars have noted that while the vocabulary items appear to be mostly related to Timucuan, Lamhatty's tribal identity remains uncertain.[30]

List of associated tribes

- Acuera

- Arapaha

- Eastern Utina (Agua Dulce)

- Itafi

- Ibi

- Icafui / Cascangue

- Northern Utina (Timucua "Proper")

- Mocoso

- Ocale

- Oconi

- Potano

- Mocama

- Surruque

- Tucururu

- Utinahica

- Yufera

- Yustaga[31]

Eastern Timucua

The largest and best known of the eastern Timucua groups were the

The Saturiwa were concentrated around the mouth of the St. Johns in what is now

Other Eastern Timucua groups lived in southeastern Georgia. The Icafui and Cascangue tribes occupied the Georgia mainland north of the Satilla River, adjacent to the Guale. They spoke the Itafi dialect of Timucua. The Yufera tribe lived on the coast opposite to Cumberland Island and spoke the Yufera dialect. The Ibi tribe lived inland from the Yufera, and had 5 towns located 14 leagues (about 50 miles) from Cumberland Island; like the Icafui and Cascangue they spoke the Itafi dialect. All these groups participated in a culture that was intermediate between the St. Johns and Wilmington-Savannah cultures. The Oconi lived further west, perhaps on the east side of the Okefenokee Swamp. Both the Ibi and Oconi eventually received their own missions, while the coastal tribes were subject to San Pedro on Cumberland Island.

Up the St. Johns River to the south of the Saturiwa were the Utina, later known as the Agua Dulce or Agua Fresca (Freshwater) tribe. They lived along the river from roughly the Palatka area south to Lake George. They participated in the St. Johns culture and spoke the Agua Dulce dialect. The area between Palatka and downtown Jacksonville was relatively less populated, and may have served as a barrier between the Utina and Saturiwa, who were frequently at war. In the 1560s the Utina were a powerful chiefdom of over 40 villages. However, by the end of the century the confederacy had crumbled, with most of the diminished population withdrawing to six towns further south on the St. Johns.

The Acuera lived along the Ocklawaha River, and spoke the Acuera dialect. Unlike most of the other Timucuan chiefdoms, they maintained much of their traditional social structure during the mission period and are the only known Timucuan chiefdom to have missions in their territory for several decades, to have left the mission system, and to have remained in their original territory with much of their traditional culture and religious practices intact despite missionization.[35]

Western Timucua

Three major Western Timucua groups, the Potano, Northern Utina, and Yustaga, were incorporated into the Spanish mission system in the late 16th and 17th centuries.[36][6][24]

The Potano lived in north central Florida, in an area covering Alachua County and possibly extending west to Cofa at the mouth of the Suwannee River. They participated in the Alachua culture and spoke the Potano dialect. They were among the first Timucua peoples to encounter Europeans. They were frequently at war with the Utina tribe, who managed to convince first the French and later the Spanish to join them in combined assaults against the Potano. They received missionaries in the 1590s and five missions were built in their territory by 1633. Like other Western Timucua groups they participated in the Timucua Rebellion of 1656.[37]

North of the Potano, living in a wide area between the

On the other side of the Suwannee River from the Northern Utina were the two westernmost Timucuan groups, the Yustaga and the Asile.[38] They lived between the Suwannee and the Aucilla River, which served as a boundary with the Apalachee. The Yustaga participated in the same Suwanee Valley culture as the Northern Utina, but appear to have spoken a different dialect, perhaps Potano. Unlike other Timucua groups, the Yustaga resisted Spanish missionary efforts until well into the 17th century. They maintained higher population levels significantly later than other Timucua groups, as their less frequent contact with Europeans kept them freer of introduced diseases. Like other Western Timucua groups, they participated in the Timucua Rebellion. The Asile, living immediately east of the Aucilla River, were described in early contact accounts as "a subject of Apalachee", and held some land on the western side of the Aucilla in the territory of the Apalachee chief of Ivitachuco.[38]

Other Western Timucua tribes are known from the earliest Spanish records, but later disappeared. The most significant of these are the

Some scholars such as Julian Granberry, have suggested that the Tawasa people of Alabama spoke a language related to Timucua based on lexical similarities. The only surviving written Tawasa text is an account from an indigenous man named Lamhatty. Others like Hann have cast doubt on this theory on the basis that only some words appear to be cognates, and that the Tawasa are never described as Timucua in the historical record despite frequent European encounters with them. Swanton suggests based on village placenames that the Tawasa were a confederacy of peoples with "Muskhogean, Timucua, and Yuchi affiliations.[30]

Organization and classes

The Timucua were not a unified political unit. Rather, they were made up of at least 35 chiefdoms, each consisting of about two to ten villages, with one being primary.

Villages were divided into family clans, usually bearing animal names. Other villages bore the name of the residing chieftain.[41] Children always belonged to their mother's clan.

Customs

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

The Timucua played two related but distinct ball games. Western Timucua played a game known as the "Apalachee ball game". Despite the name, it was as closely associated with the western Timucua as it was with the Apalachee. It involved two teams of around 40 or 50 players kicking a ball at a goal post. Hitting the post was worth one point, while landing it in an eagle's nest at the top of the post was worth two; the first team to score eleven points was the victor. The western Timucua game was evidently less associated with religious significance, violence, and fraud than the Apalachee version, and as such missionaries had a much more difficult time convincing them to give it up.[42][43]

The eastern Timucua played a similar game in which balls were thrown, rather than kicked, at a goal post. The Timucua probably also played

The chief had a council that met every morning when they would discuss the problems of the chiefdom and smoke. To initiate the meeting, the White Drink ceremony would be carried out (see "Diet" below). The council members were among the more highly respected members of the tribe. They made decisions for the tribe.

Settlements

The Timucua of northeast Florida (the Saturiwa and Agua Dulce tribes) at the time of first contact with Europeans lived in villages that typically contained about 30 houses, and 200 to 300 people. The houses were small, made of upright poles and circular in shape. Palm leaf thatching covered the pole frame, with a hole at the top for ventilation and smoke escape. The houses were 15 to 20 feet (4.5 to 6 m) across and were used primarily for sleeping. A village would also have a council house which would usually hold all of the villagers. Europeans described some council houses as being large enough to hold 3,000 people. If a village grew too large, some of the families would start a new village nearby, so that clusters of related villages formed. Each village or small cluster of related villages had its own chief. Temporary alliances between villages for warfare were also formed. Ceremonial mounds might be in or associated with a village, but the mounds belonged to clans rather than villages.[44]

Diet

The Timucua were a semi-agricultural people and ate foods native to North Central Florida. They planted food crops such as

In addition to agriculture, the Timucua men would hunt game (including alligators, manatees, and maybe even whales); fish in the many streams and lakes in the area; and collect freshwater and marine shellfish. The women gathered wild fruits, palm berries, acorns, and nuts; and baked bread made from the root koonti. Meat was cooked by boiling or over an open fire known as the barbacoa, the origin of the word barbecue. Fish were filleted and dried or boiled. Broths were made from meat and nuts.

After the establishment of Spanish missions between 1595–1620, the Timucua were introduced to European foods, including barley, cabbage, chickens, cucumbers, figs, garbanzo beans, garlic, European grapes, European greens, hazelnuts, various herbs, lettuce, melons, oranges, peas, peaches, pigs, pomegranates, sugar cane, sweet potatoes, watermelons, and wheat. The native corn became a traded item and was exported to other Spanish colonies.

A black tea called "

Physical appearance

Spanish explorers were shocked at the height of the Timucua, who averaged four inches or more above them.[citation needed] Timucuan men wore their hair in a bun on top of their heads, adding to the perception of height. Measurement of skeletons exhumed from beneath the floor of a presumed Northern Utina mission church (tentatively identified as San Martín de Timucua) at the Fig Springs mission site yielded a mean height of 64 inches (163 cm) for nine adult males and 62 inches (158 cm) for five adult women. The conditions of the bones and teeth indicated that the population of the mission had been chronically stressed.[46] Each person was extensively tattooed. The tattoos were gained by deeds. Children began to acquire tattoos as they took on more responsibility. The people of higher social class had more elaborate decorations. The tattoos were made by poking holes in the skin and rubbing ashes into the holes. The Timucua had dark skin, usually brown, and black hair. They wore clothes made from moss, and cloth created from various animal skins.

Language

The Timucua groups, never unified culturally or politically, are defined by their shared use of the Timucua language.[47] The language is relatively well attested compared to other Native American languages of the period. This is largely due to the work of Francisco Pareja, a Franciscan missionary at San Juan del Puerto, who in the 17th century produced a grammar of the language, a confessional, three catechisms in parallel Timucua and Spanish, as well as a newly-discovered Doctrina. The Doctrina, a guide for Catholics attending Mass, written in Latin with Spanish and Timucua commentary, was discovered at All Souls College Library in Oxford in 2019 by Dr. Timothy Johnson of Flagler College in St. Augustine, Florida. The last previous discovery of a lost text by Friar Pareja was in 1886.[48] The other sources for the language are two catechisms by another Franciscan, Gregorio de Movilla, two letters from Timucua chiefs, and scattered references in other European sources.[49]

Pareja noted that there were ten dialects of Timucua, which were usually divided along tribal lines. These were Timucua proper, Potano, Itafi, Yufera, Mocama, Agua Salada, Tucururu, Agua Fresca, Acuera, and Oconi.[50]

Notes

- ^ Milanich 1999, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c Milanich 2000.

- ^ a b Milanich 1999, p. 46.

- ^ Milanich 1998a, pp. 82–83, 86, 90–91.

- ^ Cassanello, Robert; Clarke, Bob (November 18, 2013). "Episode 03: Indian Canoes". A History of Central Florida (Podcast). University of Central Florida.

- ^ a b Milanich 1978, p. 62.

- ^ Weisman 1993, p. 170.

- ^ Hann 1996, pp. 41–42.

- JSTOR 43487551.

- ^ Milanich 1998a, pp. 79, 119–123.

- JSTOR 40030985.

- ^ Milanich 1998a, pp. 131–134.

- ^ Hudson 1997.

- ^ Boyer 2010, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Boyer 2017, p. 123.

- ^ Hann 1996, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Hann 1996, pp. 308–311.

- ^ Hann 1996, p. 317.

- ^ Hann 1996, p. 323.

- ^ "The First Coast's 1st People: The Timucuan Indians, Jessica Clark, First Coast News, March 9, 2015".

- ^ a b Milanich 1978, pp. 59, 62.

- ^ Deagan 1978, p. 92.

- ^ Hann 1996, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Milanich 1998b, p. 56.

- ^ Deagan 1978, pp. 95, 97–101.

- ^ Granberry 1993, pp. 4, 11.

- ^ Hann 2003, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Milanich & Hudson 1993, pp. 73–74, 76.

- ^ Hann 2003, p. 5.

- ^ a b Hann 1996, pp. 131–134.

- ^ Hann 1996, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Soergel, Matt (18 Oct 2009). "The Mocama: New name for an old people". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ Ashley 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Deagan 1978, pp. 95, 104, 108–9, 111.

- ^ Boyer 2009, p. 45.

- ^ Hann 1996, p. 9.

- ^ Hann 1996, pp. 6–7, 9, 13–14, 41–44, 154–155, 200.

- ^ a b Boyer 2021, pp. 92–94.

- ^ Hann 2003, pp. 6, 21, 24, 34–5, 105, 114, 117–8, 135.

- ^ Deagan 1978, p. 91.

- ISBN 1561642258.

- ^ a b Hann 1996, pp. 107–111.

- ^ Bushnell 1991, pp. 5, 13, 167.

- ^ Milanich 1998b, pp. 44, 46–9.

- ^ Hudson 1976.

- ^ Hoshower & Milanich 1993, pp. 217, 222, 234–5.

- ^ Milanich 1999, pp. xvii–xviii.

- ^ Johnson, Timothy (July–August 2021). "What Dreams Are Made Of: The Rediscovered Catechism 'The Mass and Its Ceremonies' of Friar Francisco Pareja". St. Augustine Catholic. pp. 18–20 – via Academia.

- ^ Granberry 1993, pp. xv–xvii.

- ^ Granberry 1993, p. 6.

References

- Ashley, Keith H. (2009). "Straddling the Florida-Georgia State Line: Ceramic Chronology of the St. Marys Region (AD 1400–1700)". In Deagan, Kathleen; Thomas, David Hurst (eds.). From Santa Elena to St. Augustine: Indigenous Ceramic Variability (A.D. 1400-1700) (PDF). New York: American Museum of Natural History. pp. 125–139.

- Boyer, Willet A. III (2009). "Missions to the Acuera: An Analysis of the Historic and Archaeological Evidence for European Interaction With a Timucuan Chiefdom". The Florida Anthropologist. 62 (1–2): 45–56. ISSN 0015-3893.

- Boyer, Willet A. III (2010). The Acuera of the Oklawaha River Valley: Keepers of Time in the Land of the Waters (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Florida. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2018.

- Boyer, Willet III (September 2017). "The Hutto/Martin Site of Marion County, Florida, 8MR3447: Studies at an Early Contact/Mission Site". The Florida Anthropologist Volume. 70 (3): 122–139 – via University of Florida Digital Collection.

- Boyer, Willet III (2021), Reexamining the Geographical and Temporal Extent of the Suwannee Valley Culture: The Floyd's Mound and South Mound Sites, The Florida Anthropologist 2021 74(2):88-106

- Bushnell, Amy (1991) [1978]. "'That Demonic Game': The Campaign to Stop Indian Pelota Playing in Spanish America, 1675-1684.". In Thomas, David Hurst (ed.). The Missions of Spanish Florida. Spanish Borderlands Sourcebooks. Vol. 23. Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8240-2098-7.

- Deagan, Kathleen A (1978). "Cultures in Transition: Fusion and Assimilation among the Eastern Timucua". In ISBN 0-8130-0535-3.

- Granberry, Julian (1993). A Grammar and Dictionary of the Timucua Language, Third Edition. The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0704-4.

- Hann, John H. (1996). A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1424-7.

- Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513-1763. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8.

- Hoshower, Lisa M.; Milanich, Jerald T. (1993). "Excavations in the Fig Springs Mission Burial Area". In McEwan, Bonnie G. (ed.). The Spanish Missions of La Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. pp. 217–243. ISBN 0-8130-1232-5.

- ISBN 0-87049-248-9.

- Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-2062-5.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1978). "The Western Timucua: Patterns of Acculturation and Change". In Milanich, Jerold T.; Proctor, Samuel (eds.). Tacachale: Essays on the Indians of Florida and Southeastern Georgia during the Historic Period. Gainesville: The University Presses of Florida. pp. 59–88. ISBN 0-8130-0535-3.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1998a). Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. Gainesville, Florida: The University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1636-3..

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1998b). Florida Indians from Ancient Times to the Present. Gainesville, Florida: The University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1599-5..

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1999). The Timucua. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-21864-5.

- Milanich, Jerold T. (2000). "The Timucua Indians of Northern Florida and Southern Georgia". In McEwan, Bonnie G. (ed.). Indians of the Greater Southeast: Historical Archaeology and Ethnohistory. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1778-5..

- Milanich, Jerald T.; Hudson, Charles (1993). Hernando de Soto and the Indians of Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-1170-7.

- Weisman, Brent R. (1993). "Archaeology of Fig Springs Mission, Ichetucknee Springs State Park". In McEwan, Bonnie G. (ed.). The Spanish Missions of La Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. pp. 165–192. ISBN 0-8130-1232-5.

Further reading

- Boyer, Willet III (September–December 2015). "Potano in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries: New Excavations at the Richardson/UF Village Site, 8AL100". The Florida Anthropologist. 68 (3–4): 75–96 – via University of Florida Digital Collection.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Hodge, Frederick Webb, ed. (1910). "Timucua". Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin. Vol. 30. pp. 752–754.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (2004). "Timucua". In Fogelson, R. D. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 219–228. ISBN 0-16-072300-0..

- Swanton, John R. (1946). The Indians of the Southeastern United States. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletins. Vol. 137. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office – via HathiTrust.

- Worth, John (1998a). The Timucuan Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida: Volume I: Assimilation. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press. ISBN 978-0-8130-6839-8.

- Worth, John (1998b). The Timucuan Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida: Volume II: Resistance and Destruction. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press. ISBN 978-0-8130-6840-4.

External links

- Florida of the Indians

- More about Timucua Indians Archived 2014-08-26 at the Wayback Machine

- A History of Central Florida Podcast - Indian Canoes, Celts, Hotoon Owl Totem

- SJCPLS Video: Dr. Timithy Johnson's 2019 Discovery of a Rare Timucua Book

- New-York Historical Society, Five Timucua Language Imprints, 1612-1635

- Pareja, Francisco. 1628. IIII parte del catecismo, en lengua Timuquana, y castellano. En que se trata el modo de oyr Missa, y sus ceremonias. Mexico City:Imprenta de Iuan Ruyz. (In the Codrington Library, Oxford.)

- Timucua Dictionary