Toba Batak people

Deli Serdang , and the surrounding areas – 3,000,000

Outside North Sumatera: Riau, Batam, Jakarta, Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Papua, Bali, and around Indonesia – 1,100,000 [1] Outside Indonesia: | |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Toba Batak language, Indonesian language | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity 97.8%, Sunni Islam 2%, Other 0.2%[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Angkola people, Karo people, Mandailing people, Pakpak people, Simalungun people |

Toba Batak people (

The Toba people are found in

Paleontological research done in the Humbang region of the west side of

History

Batak kingdoms

There were numerous kingdoms and dynasties in the history of the Batak and Toba Batak people. The last dynasty in the Toba Batak people is the Sisingamangaraja dynasty with twelve successive priest kings called ‘Sisingamangaraja’ from the Sinambela clan. During the time when the Batak kingdom was based in Bakara, the Sisingamangaraja dynasty of the Batak kingdom divided their kingdom into four regions by the name of Raja Maropat, which are:[5]

- Raja Maropat Silindung

- Raja Maropat Samosir

- Raja Maropat Humbang

- Raja Maropat Toba

Dutch colonization

The Dutch colonization starts with the defeat of King

- Afdeling Padang Sidempuan.

- Afdeling Nias, which later became Nias Regency and South Nias Regency.

- Afdeling Sibolga and Ommnenlanden, today it is Central Tapanuli Regency and Sibolga.

- Afdeling Bataklanden, which later became .

Japanese occupation

During the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, the administration of the Tapanuli Residency had little changes.

Post-independence of Indonesia

After the independence, the government of Indonesia retains Tapanuli as

Although there were changes made to the name, the division of the region was still the same. For example, the name of Afdeling Bataklanden was changed to Luhak Tanah Batak and the first luhak (federated region) appointed was Cornelius Sihombing; who was once also a demang (chief) silindung. The title Onderafdeling (in the Dutch language means, subdivision) is also changed to urung, and demangs that supervise onderafdeling are promoted as kepala (head) urung. Onderdistrik (subdistrict) then became urung kecil, and was supervised by kepala urung kecil; which was previously known as assistant demang.

Just as it was in the past, the government of the Tapanuli Residency was divided into four districts, namely:

Transfer of sovereignty in early 1950

During the transfer of sovereignty in the early 1950s, the Tapanuli Residency that was unified into North Sumatra provinceand were divided into four new regencies, namely:-

- Tanah Batak Regency)

- Sibolga Regency)

- Padang Sidempuan Regency)

- Nias Regency

Present

In December 2008, the Tapanuli Residency was unified under

Culture

The Toba Batak people practice a distinct culture. The central foundation of their culture is the

The Toba Batak people are known to possess a robust tradition of ‘Mangaranto‘ or becoming migrants to look for better education, and social and economic opportunities. There is no obligation for Toba people to live in the Toba region, although they are obliged to be attached to their original village in Toba. The original village or Bius of a Toba Batak person is called ‘Bona Pasogit‘. It is often for a Toba Batak person to identify his/her origin not by their birthplaces, but by their Bona Pasogit in ‘Tano Batak‘ or ‘The Batak Land’.[7]

Just as it is with other ethnicities, the Toba people have also migrated to other places to look for a better life. For example, the majority of the Silindung natives are the Hutabarat, Panggabean, Simorangkir, Hutagalung, Hutapea and Lumbantobing clans. Instead all those six clans are actually descendants of Guru Mangaloksa, one of Raja Hasibuan's sons from Toba region. So it is with the Nasution clan where most of them live in Padangsidimpuan, surely share a common ancestor with their relative, the Siahaan clan in Balige. It is certain that the Toba people as a distinct culture can be found beyond the boundaries of their geographical origins. According to the folklore of the Batak people, the first ancestor of the Batak people is Si Raja Batak , literally means ‘King Batak’ or ‘the King of Batak’. His origin is believed to be from a Toba village known as Sianjur Mula village, situated on the slopes of Mount Pusuk Buhit, about 45 minutes drive from Pangururan, the capital of Samosir Regency today.

The Toba Clans and Families

A surname or family name (marga) is part of a Toba person's name, which identifies the clan or family they belonged to. The Batak Toba people always have a surname or family name. The surname or family name is obtained from the father's lineage (paternal) which would then be passed on to the offspring continuously. Nainggolan, Napitupulu, Pardede, Gultom, Panggabean, Silalahi, Siahaan, Simanjuntak, Sihombing, Sitorus, Panjaitan, Sitompul, Marbun, Lumban Tobing, Aritonang, Pangaribuan, Situmorang, Manurung, Marpaung, Hutapea, Tambunan, Silitonga, Tampubolon, Sinaga, Siregar, Pakpahan, Sidabutar, Aruan, Ambarita, and Simatupang are among the popular surnames. However, the number of all Toba Batak clans are in hundreds.

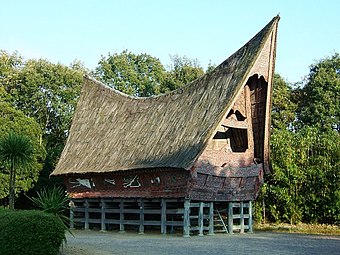

Traditional house

-

A traditional Toba house.

-

House of a Toba Batak chief.

-

Rumah Bolon (Big house), Toba Batak house

-

Giorognom-giorognom (carving at the top of a Toba house) and signa (figurehead on either side of a Toba house)

-

Rumah Bolon (Jabu bolon)

The traditional house of the Toba people is called

Boat

The traditional boat of the Toba Batak people is the solu. It is a dugout canoe, with boards added on the side bound with iron tacks. The boat is propelled by sitting rowers, who sit in pairs on cross seats.[8]

Views of Toba people in Indonesian culture

The Toba Batak are known throughout Indonesia as capable musicians, and are perceived as confident, outspoken and willing to question authority, expressing differences in order to resolve them through discussion. This outlook on life is contrasted to Javanese people, Indonesia's largest ethnic group, who are more culturally conciliatory and less willing to air differences publicly.[9] Batak Toba people also known as professing christians in contrast with the largely Muslim population in Indonesia. In terms of occupational sector, Batak Toba is also known to be well represented in some sectors particularly law, education, military, economy, and politics.

Religion

An overwhelming majority of the Toba Batak people are adherents of

Most of the Toba people are adherents of

The first Protestant missionaries who tried to reach the Batak highlands of inner Northern Sumatra were English and American Baptist preachers in the 1820s and 1830s but without any success. After Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn and Herman Neubronner van der Tuuk did intensive research on Batak language and culture in the 1840s, a new attempt was done in 1861 by several missionaries sent out by the German Rhenish Missionary Society (RMG). The first Bataks were baptized during this year. In 1864, Ludwig Ingwer Nommensen from the German Rhenish Missionary Society reached the Batak region and founded a village called "Huta Dame" (village of peace) in the district of Tapanuli in Tarutung, North Sumatra.[12]

The Batak Christian Protestant Church (Indonesian: Huria Kristen Batak Protestan) is the largest Protestant church with Lutheranism in Indonesia. It was founded by the German missionaries and still regarded as the traditional church of the Toba Batak people. In the early 20th century, HKBP disported into several independent Protestant churches such as GKPS (Simalungun) and GKPA (Angkola) to accommodate church services for the Batak people outside of the Toba community.

Before the conversion to Christianity, the old belief of the Toba Batak tribe was a mixture of Animism and Hinduism with significant influence of Islam. In the beginning of the 20th century, some Toba Batak Rajahs who refused to embrace Christianity instituted a religion inspired by the pre-Christian Toba Batak beliefs, customs and practices. This religion is called ‘ Ugamo Malim ‘ with its adherents called Parmalim. The Parmalims worship Debata Mula Jadi Nabolon, which means The Great Almighty God.[13]

A minority of Toba Batak are adherents of Sunni Islam. Many of the Muslim Toba Batak are originated from port of Barus, Sorkam, parts of Sibolga, and from Asahan areas. They are generally regarded as the original Toba Batak Muslims, although, sometimes the Batak Muslims from these regions are identified and self-identified as distinct sub-group known as ‘Orang Pesisir’ or ‘Batak Pesisir’ and ‘Batak Pardembanan’ (Asahan). In some cases of conversion to Islam, there are occurrences of Toba Batak Muslims disassociating themselves with Toba Batak customs and identity and prefer association with other ethnic identities (e.g. of their spouses) or to disassociate ethnic identity at all. This would cause the departure from the traditional Toba Batak customs and adoption of the more conventional Islamic customs in instances such as wedding or burial, as many aspects of the former are now seen as no longer compatible with Islamic standard.[14]

See also

References

Constructs such as named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (March 2024) ) |

- ^ Jacob Cornelis Vergouwen, Masyarakat dan hukum adat Batak Toba

- ^ "Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Toba Samosir". tobasamosirkab.bps.go.id.

- ISBN 9-7933-8142-6.

- ^ Mapping Human Genetic Diversity in Asia, The HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium (2009)

- ^ Julia Suzanne Byl (2006). Antiphonal Histories: Performing Toba Batak Past and Present. University of Michigan.

- ^ Julia Suzanne Byl (2006). Antiphonal Histories: Performing Toba Batak Past and Present. University of Michigan.

- ^ Op Cit.

- ^ Giglioli (1893). p. 116.

- ^ "Apakah Ini Alasan Mengapa Banyak Orang Batak Jago Nyanyi". www.mistar.id (in Indonesian). 18 July 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Warneck, Johannes 1894a ‘Bilder aus dem Missionsleben in Toba’, Allgemeine Missions Zeitschrift, Beiblatt 7-14

- ^ a b van Bemmelen, S. T. (2012). Good Customs, Bad customs in North Sumatra: Toba Batak, Missionaries and Colonial Officials Negotiate the Patrilineal Order (1861-1942). In eigen beheer. P. 14

- ^ Sitompul, Martin (22 April 2020). "Aksi Nommensen di Tanah Batak". www.historia.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Napitupulu, Sahala (2008). "BATAK BUKAN BAKAT: Parmalim Antara Agama Dan Budaya Batak"

- ^ Ritonga, S.(2012:260) Orientasi Nilai Budaya dan Potensi Konflik Sosial Batak Toba Muslim dan Kristen di Sumatera Utara (Studi Kasus Gajah Sakti Kabupaten Asahan). IAIN Sumatera Utara. Medan

Further reading

- Bertha T. Pardede; Apul Simbolon; S. M. Pardede (1981), Bahasa Tutur Perhataan Dalam Upacara Adat Batak Toba, Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, OCLC 19860686

- Giglioli, Henry Hillyer (1893). Notes on the Ethnographical Collections Formed by Dr. Elio Modigliani During His Recent Explorations in Central Sumatra and Engano in Intern. Gesellschaft für Ethnographie; Rijksmuseum van Oudheden te Leiden (1893). Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie volume VI. Getty Research Institute. Leiden : P.W.M. Trap.