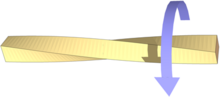

Torsion (mechanics)

In the field of

In non-circular cross-sections, twisting is accompanied by a distortion called warping, in which transverse sections do not remain plane.[1] For shafts of uniform cross-section unrestrained against warping, the torsion is:

where:

- T is the applied torque or moment of torsion in Nm.

- (tau) is the maximum shear stress at the outer surface

- JT is the torsion constant for the section. For circular rods, and tubes with constant wall thickness, it is equal to the polar moment of inertia of the section, but for other shapes, or split sections, it can be much less. For more accuracy, finite element analysis (FEA) is the best method. Other calculation methods include membrane analogy and shear flow approximation.[2]

- r is the perpendicular distance between the rotational axis and the farthest point in the section (at the outer surface).

- ℓ is the length of the object to or over which the torque is being applied.

- φ (phi) is the angle of twist in radians.

- G is the shear modulus, also called the lbf/in2(psi), or lbf/ft2 or in ISO units N/mm2.

- The product JTG is called the torsional rigiditywT.

Properties

The shear stress at a point within a shaft is:

Note that the highest shear stress occurs on the surface of the shaft, where the radius is maximum. High stresses at the surface may be compounded by

The angle of twist can be found by using:

Sample calculation

Calculation of the steam turbine shaft radius for a turboset:

Assumptions:

- Power carried by the shaft is 1000 MW; this is typical for a large nuclear powerplant.

- Yield stressof the steel used to make the shaft (τyield) is: 250 × 106 N/m2.

- Electricity has a frequency of 50 Hz; this is the typical frequency in Europe. In North America, the frequency is 60 Hz.

The angular frequency can be calculated with the following formula:

The torque carried by the shaft is related to the power by the following equation:

The angular frequency is therefore 314.16

The maximal torque is:

After substitution of the torsion constant, the following expression is obtained:

The diameter is 40 cm. If one adds a factor of safety of 5 and re-calculates the radius with the maximum stress equal to the yield stress/5, the result is a diameter of 69 cm, the approximate size of a turboset shaft in a nuclear power plant.

Failure mode

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2014) |

The shear stress in the shaft may be resolved into

In the case of thin hollow shafts, a twisting buckling mode can result from excessive torsional load, with wrinkles forming at 45° to the shaft axis.

See also

- List of area moments of inertia

- Saint-Venant's theorem

- Second moment of area

- Structural rigidity

- Torque tester

- Torsion siege engine

- Torsion spring or -bar

- Torsional vibration

References

- ^ Seaburg, Paul; Carter, Charles (1997). Torsional Analysis of Structural Steel Members. American Institute of Steel Construction. p. 3.

- ^ Case and Chilver "Strength of Materials and Structures

- S2CID 139371841.

External links

The dictionary definition of torsion at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of torsion at Wiktionary Solid Mechanics at Wikibooks

Solid Mechanics at Wikibooks